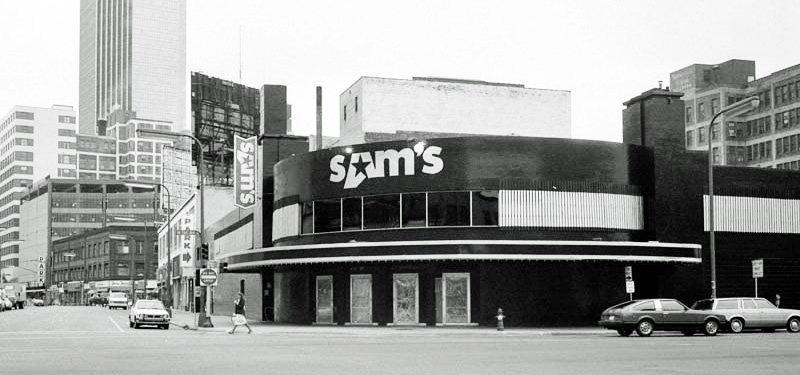

Depot, Uncle Sam’s, and Sam’s

Seventh Street No. and First Ave. No

Minneapolis

This page is about the legendary clubs that have been located at the corner of Seventh Street No. and First Ave. No. in Minneapolis.

I. INTRODUCTION

First I’ll lay out some things to take into consideration when reading this page, introduce the founders of the Depot, and direct you to my sources.

II. THE MUSIC

Next is the story of the music and other goings-on at the Depot, Uncle Sam’s, and Sam’s, with ads, posters, photos, tickets, show reviews, etc.

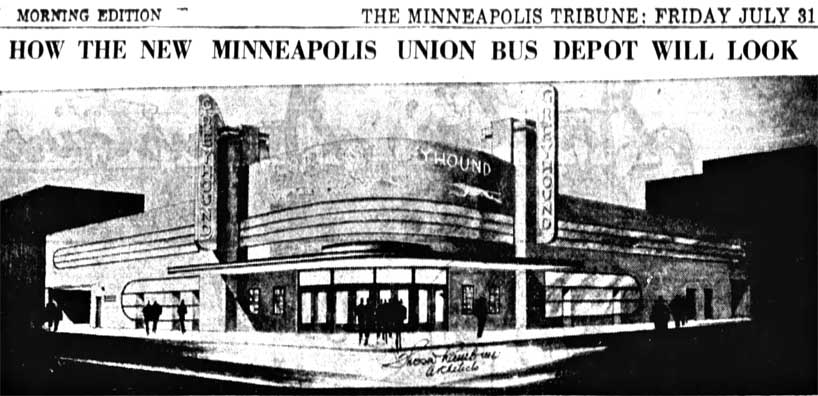

III. BEFORE THE MUSIC

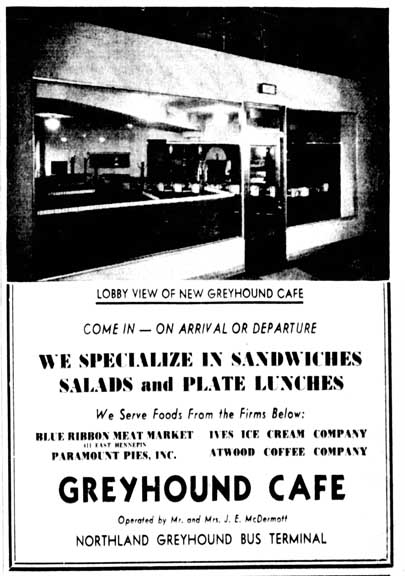

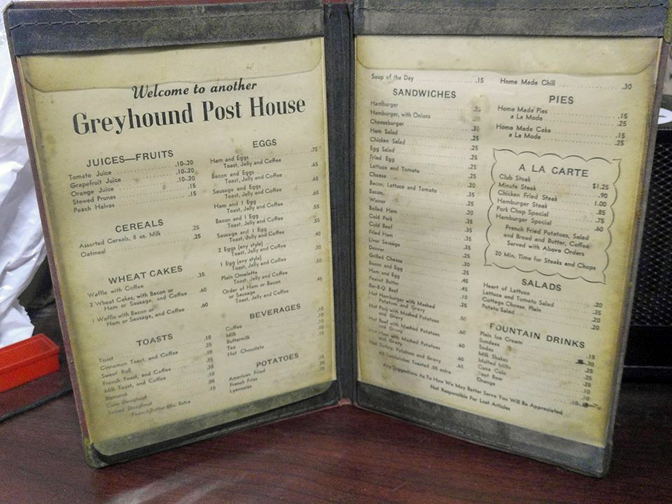

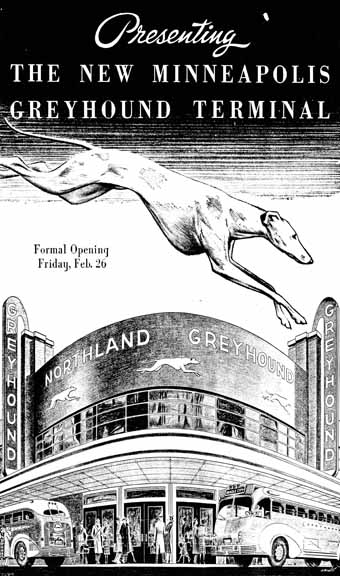

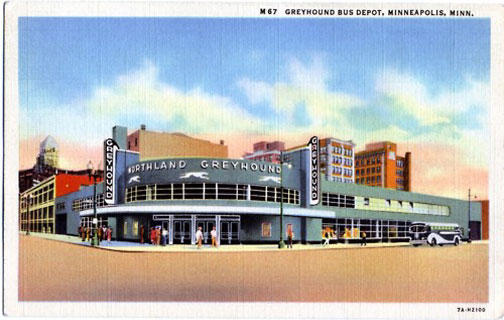

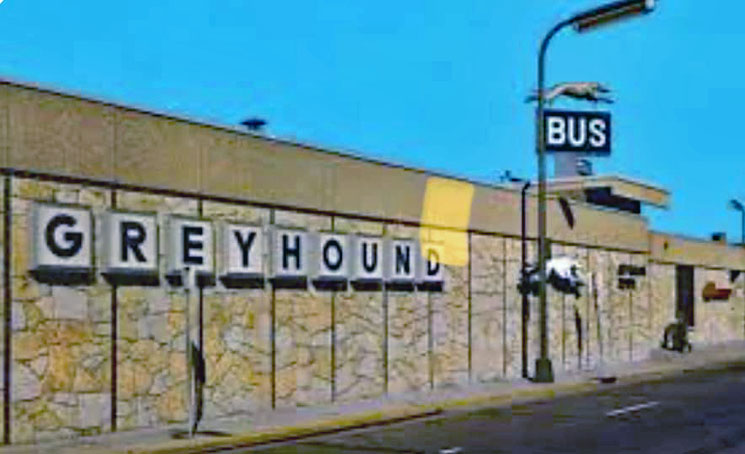

This section looks at the history of the site, going back to its first uses – as a grade school, believe it or not – an office building/bus station, and of course the City’s Greyhound bus depot. This is undoubtedly more than you’ll ever want to know, but this is called going down the rabbit hole…

IV. HISTORY OF THE COMMITTEE, INC.

The last section focuses on the history of the organization that started the Depot and owned each club until First Avenue’s bankruptcy in 2004. This includes the people who turned an old bus terminal into the hippest place in town, and the machinations that happened along the way.

I. INTRODUCTION

NOTES

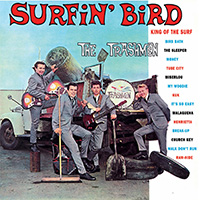

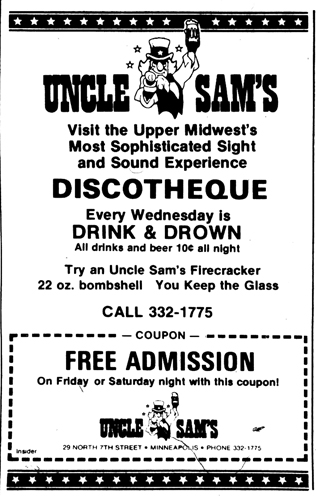

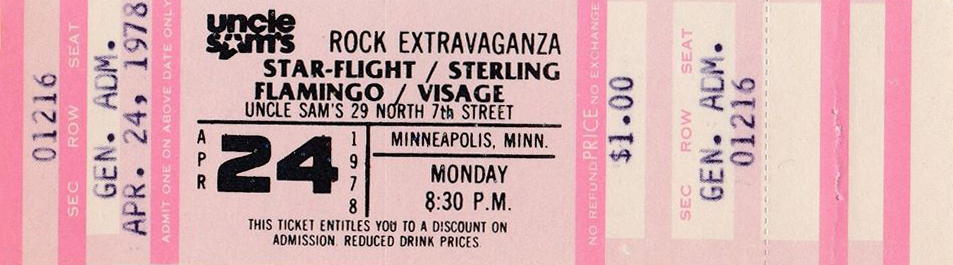

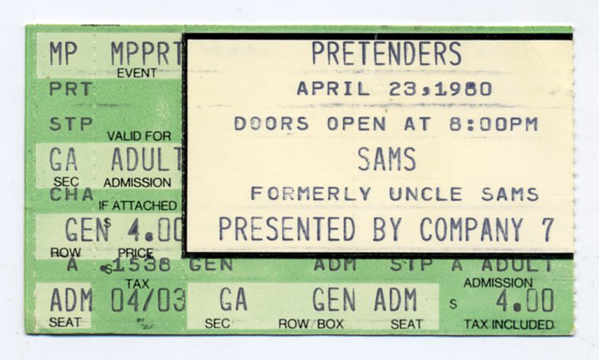

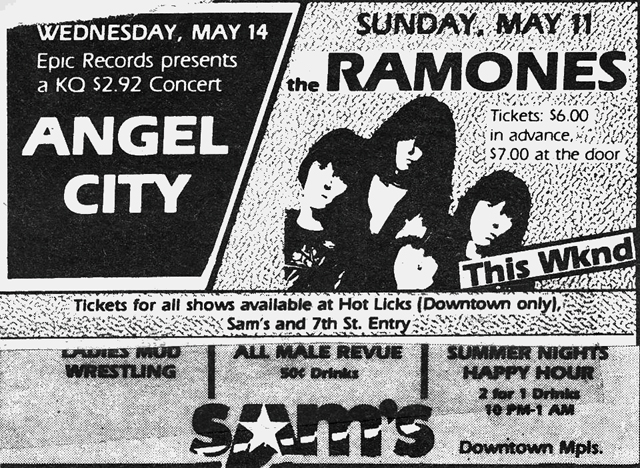

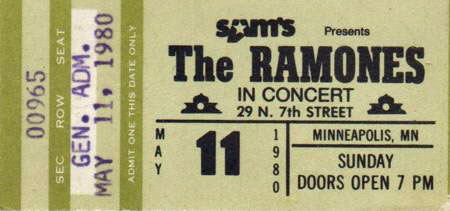

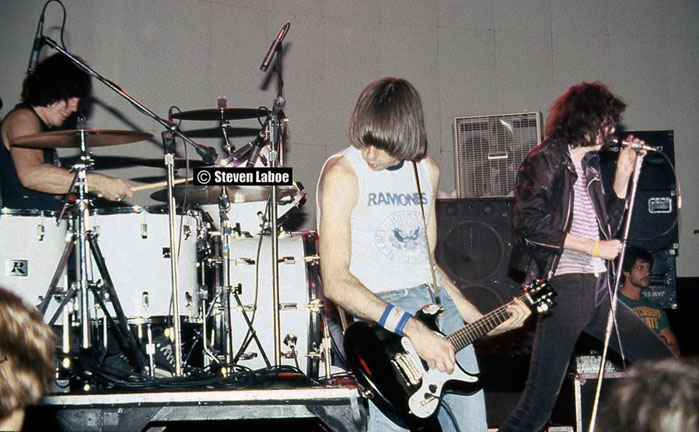

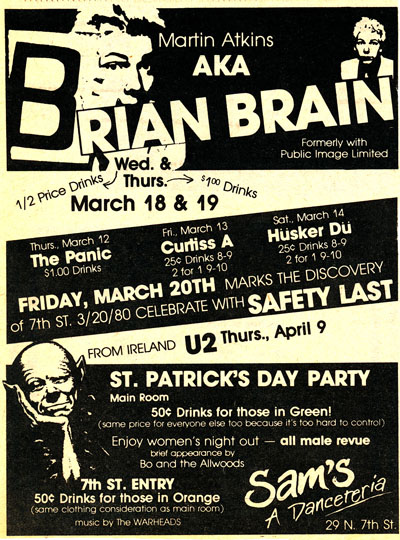

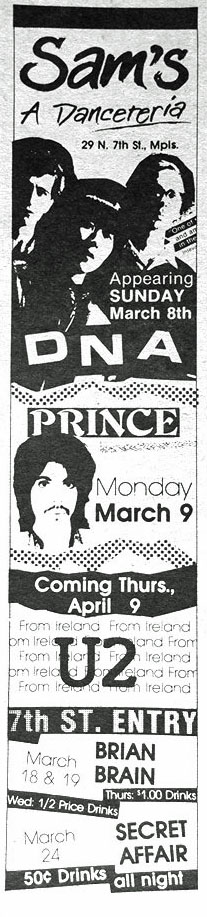

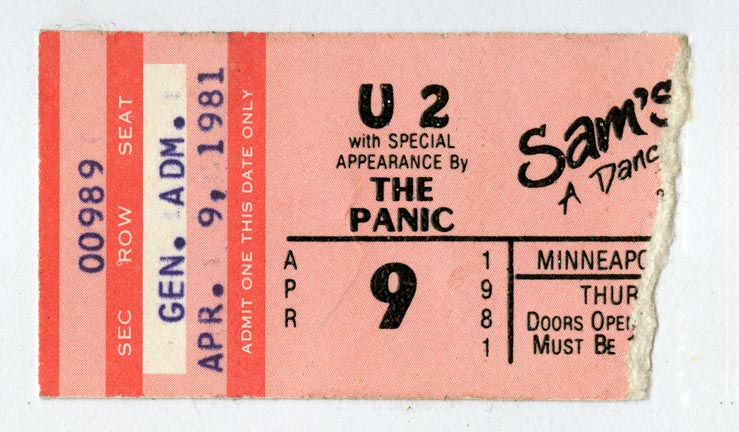

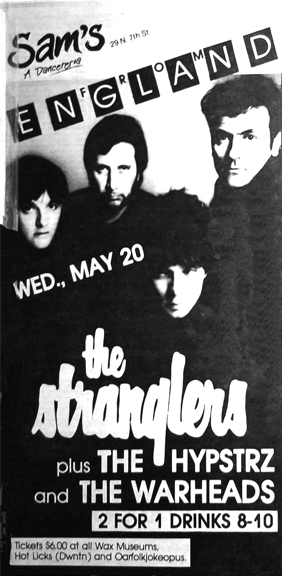

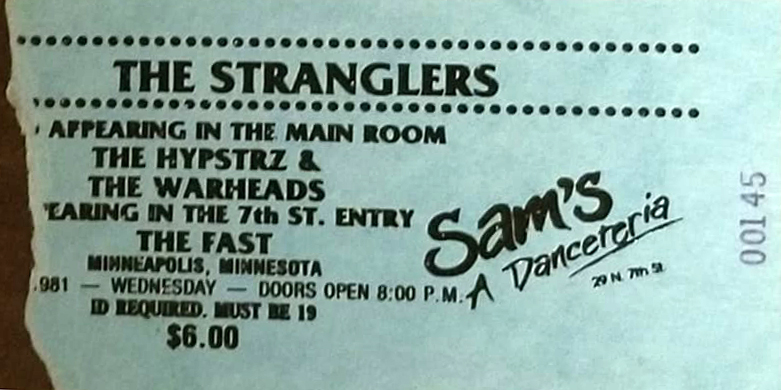

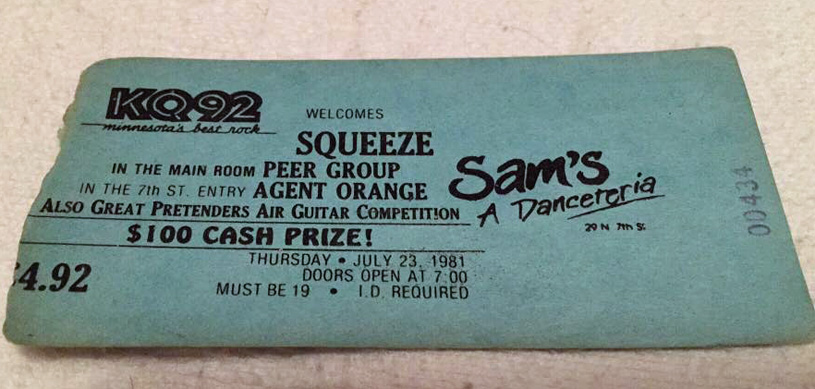

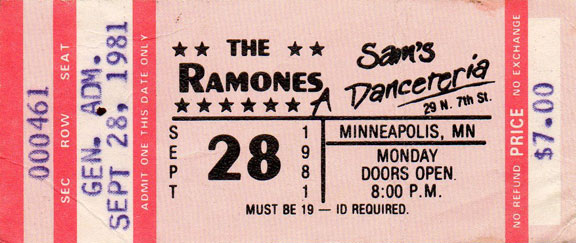

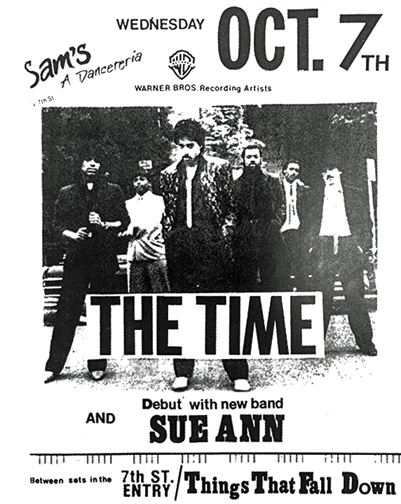

As a rule, this entire website focuses on Twin Cities music through 1974 but I’ve made a slight exception here. This page will cover the Depot, which began in 1970; Uncle Sam’s, which began in 1972; and Sam’s, which began in 1980. 7th Street Entry (March 21, 1980) and First Avenue (January 1, 1982) will not be covered here, except for information on the Committee in Section IV.

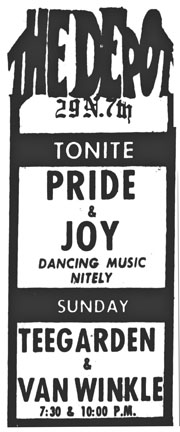

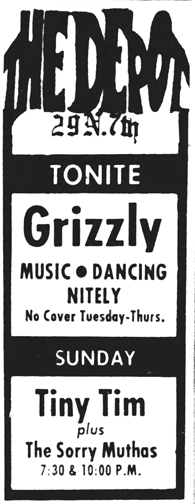

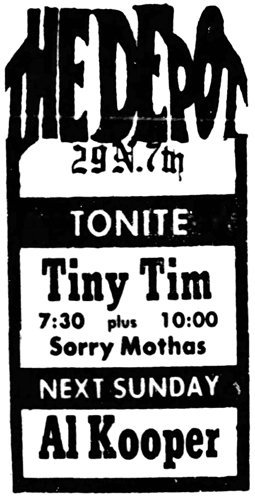

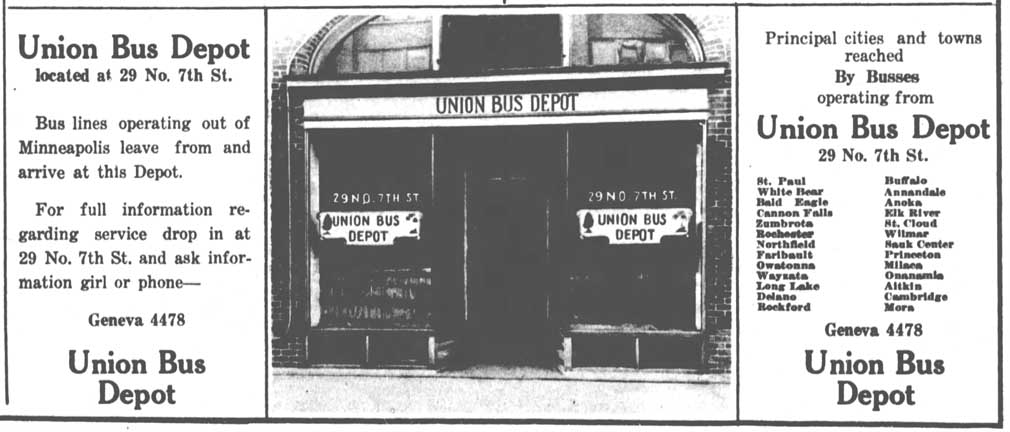

About the address: during the bus station, Depot, and Uncle Sam’s days, the address of the building was given as 29 Seventh Street No. At some point it reverted to its actual address of 701 First Ave. No. How the other address came into play is a question to be answered.

A bit of trivia: First Avenue was originally called Utah Avenue.

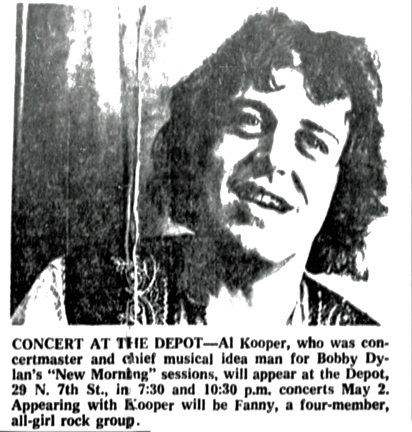

And just so I don’t have to keep repeating it, Will Jones was the wonderful entertainment columnist for the Minneapolis Tribune. Yes, he was a little old to appreciate rock venues, and those “girl watching” features wouldn’t pass the muster today, but his columns held a wealth of information about popular culture and what was going on around Minneapolis. Thank goodness for Will Jones!

THE FOUNDERS

The following are thumbnail sketches of the four original members of The Committee, the organization that created the Depot.

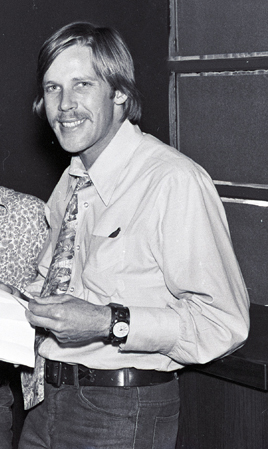

DANNY STEVENS

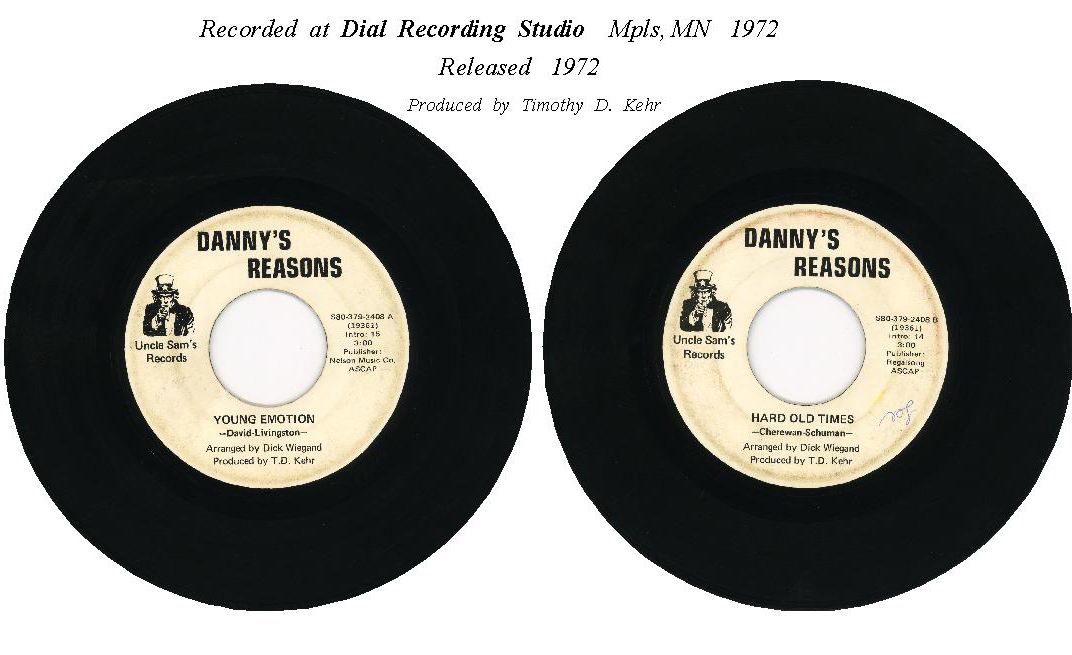

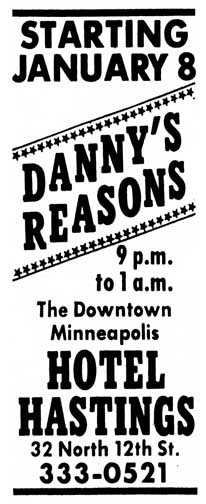

Danny Stevens was always very athletic, participating in water skiing and Golden Gloves Boxing from ages 10 to 17. He graduated from West High School in 1961, and studied pre-med at the University of Minnesota. In 1964 his first band, Danny and the Nightsounds, won the Battle of the Bands at the 1964 Teen Fair at the State Fair. Later that year he started Danny’s Reasons, a tremendously successful band that would last for decades and include many different members along the way. Danny’s Reasons played in dozens of local clubs in the area. The band was inducted into the Mid-America Music Hall of Fame in 2007.

Statements made by or information received from Danny are marked (DS)

ALLAN FINGERHUT

Allan was the son of Manny Fingerhut, who had founded Fingerhut Manufacturing Co., a company that started out making seat covers for cars. The Fingerhut catalog empire created innovative ways for people to buy goods on time and with a special Fingerhut credit card. This made Manny a millionaire. Allan was one of Manny and Rose’s three children. He was born in 1944 and graduated from St. Louis Park High School in 1962. After high school he attended the New York School of Design, and served in the Army.

Thanks to the efforts of David Roth and Allan’s daughter Rain, I was able to have an extensive telephone conversation with Allan and his wife Rose. Although he was already suffering from the effects of Lewy Bodies Dementia, which made it difficult to remember some things, he did remember many people and was interested to know what had become of them. I am very grateful for the opportunity to have talked with him. Statements made by or information received from Allan are marked (AF). Allan passed away on October 12, 2020, and was interred at Lakewood Cemetery, Minneapolis.

SHARRON FINGERHUT

Sharron was married to Allan from 1965 to 1974, and they had two children. Sharron served as the Secretary and/or Treasurer of The Committee from 1970 to 1976. Her last name is now Grohoski.

ABBY ROSENTHAL

Abbott “Abby” Rosenthal graduated from St. Louis Park High School High School in 1959. He was tapped to be the first General Manager of the Depot because he had filled the same job at George’s in the Park in St. Louis Park. Abby was not with the Depot for very long. He was an artist when he died in 2016.

I went ’round and ’round about where to put my sources. I have made a special effort to credit each source I’ve used, and there are a lot of them. The list is identified by abbreviations that are used throughout this page, so you might want to refer to them as you read. So I decided to put them on a separate page so you can toggle between them instead of scrolling up and down. I hope that is useful. If not, please let me know.

II. THE MUSIC

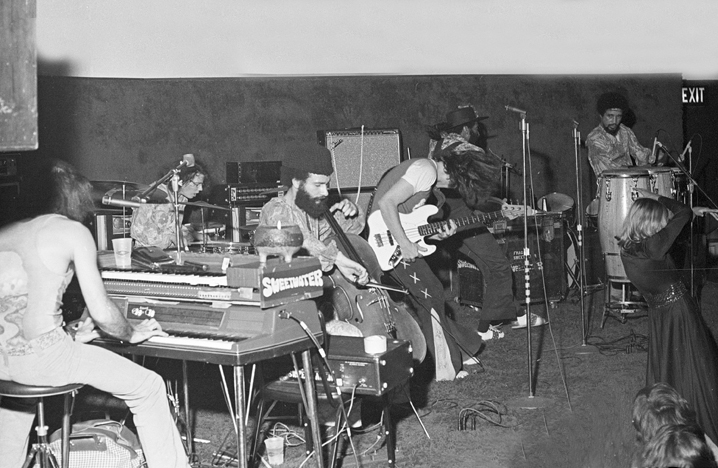

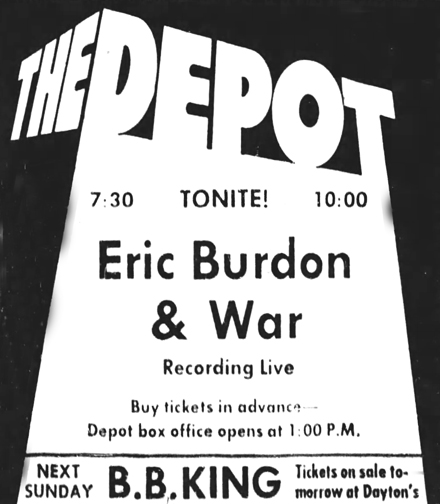

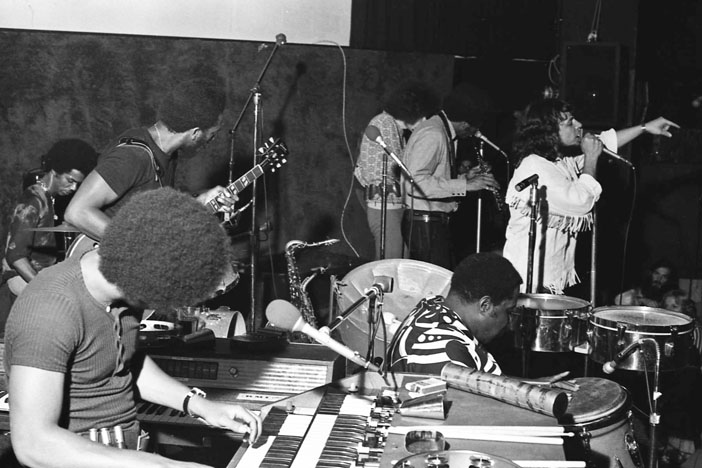

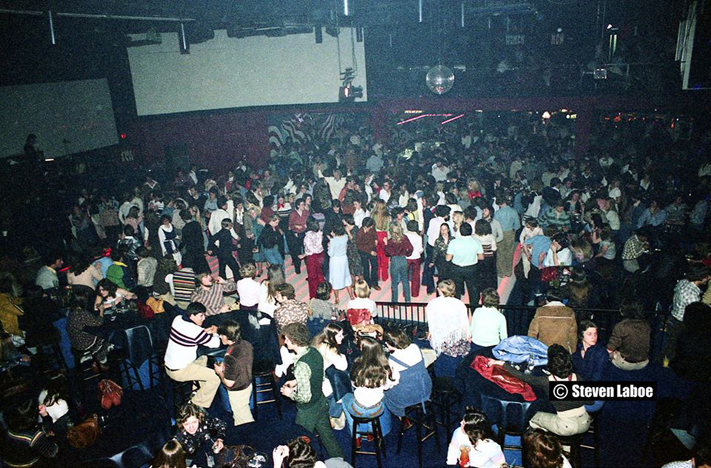

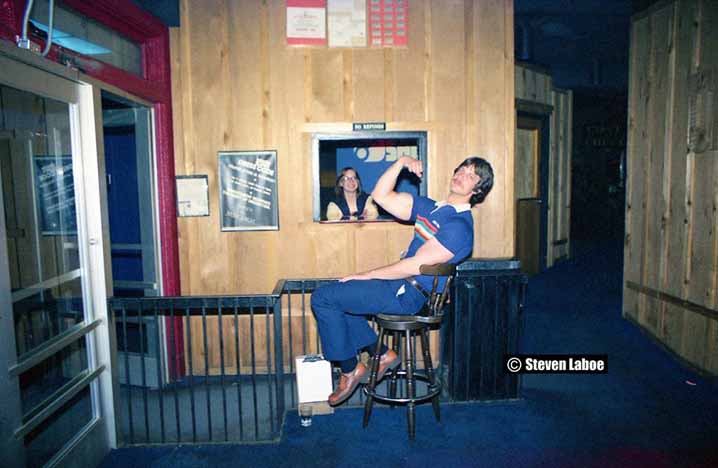

In this section I will try to list as many of the shows presented at the Depot, Uncle Sam’s, and Sam’s as I’ve been able to find, augmented with reviews, photos, posters, and anything else floating around. I’m sure there were many more shows to find. Ads are from the Minneapolis Star and Tribune unless otherwise attributed. Please note that the synopses of the reviews are my interpretations of longer articles. If you have any photos or stories to share, and by all means if you have any corrections, please contact me!

EARLY PRESS

January 10, 1970, Connie’s Insider: Connie Hechter was the editor of Connie’s Insider, a music magazine that started in 1967 and ran until Connie’s death in 1978.

Connie got the jump on the first press announcement of the new club, even before the application for the liquor license was submitted:

Danny Stevens and Abby Rosenthal will team together (Rosenthal formerly was with the management at George’s in the Park) to open the defunct, or vacated Bus Depot….the old one. It will make a great club and is an outstanding downtown Minneapolis location, if Ted Mann doesn’t build a theatre on the property in the near future. He owns the land, so I’m told. He also owns most of the show houses downtown.

February 7, 1970, Connie’s Insider: “Oh yes, the new club that Danny Stevens and Abby Rosenthal will open in April is also co-owned by Allan Fingerhut. I forgot to mention that in the last issue. In fact, if it wasn’t for Mr. Fingerhut, there would be no Depot.”

HELP WANTED AND MORE PRESS

On February 20, 1970, this ad appeared in the Minneapolis Star. It was a different time, folks.

February 22, 1970, Minneapolis Tribune: An article by Allan Holbert was called “Shops, Night Club to Open.” Interesting that he listed the shops first.

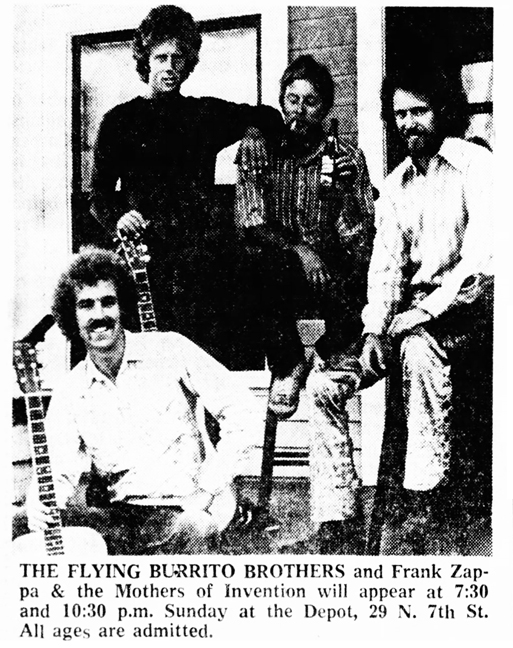

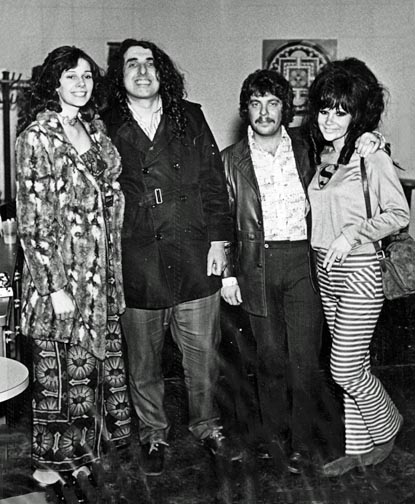

Original caption: Danny Stevens, left; Allan and Sharron Fingerhut; Abbott Rosenthal

Holbert:

Management

Owner of the Depot is a new corporation called the Committee. Allan Fingerhut, whose family is a major owner of the Fingerhut Manufacturing Corp., is chairman of the board. Danny Stevens, head of Danny’s Reasons rock band, is president.

Managing the 40 or so employees will be Abby Rosenthal, former manager of George’s in the Park.

With regard to the shops, the article gave out with some very ambitious plans, which didn’t materialize:

- Two clothing stores:

- I, Ross

- East-West Ltd.

- A Record shop

- A Novelty shop

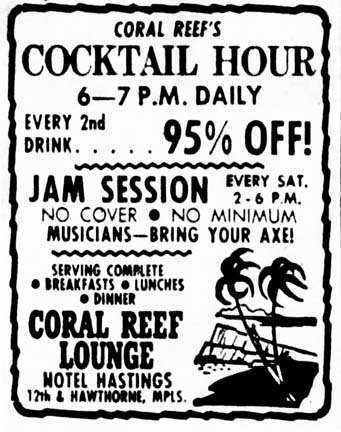

- Three bars (there were eventually at least five). One of the bars, The Second Floor of the World, “will have low-priced drinks and is expected to attract some of the 5 o’clock trade of young working people who now frequent such places as Buster’s and Duff’s.”

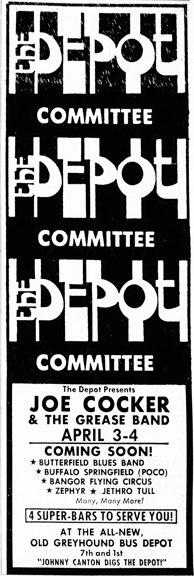

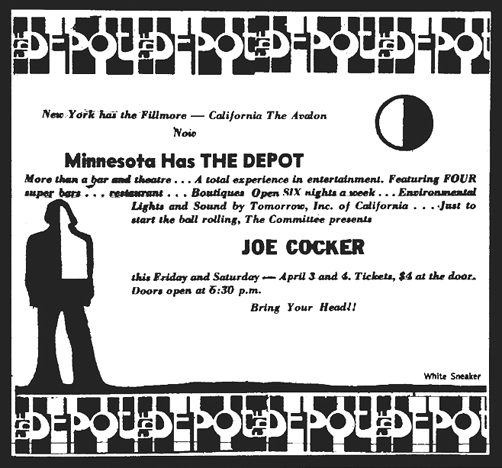

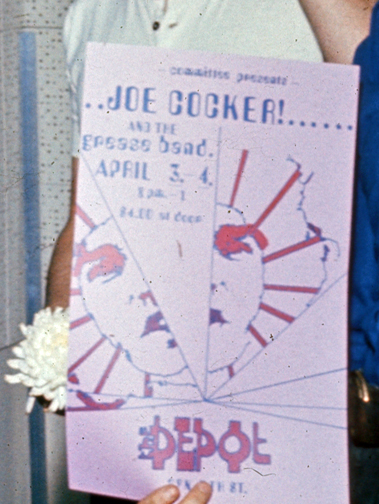

Holbert noted that the venue would be opened by Joe Cocker on April 3 and 4, 1970, (which it was), but also listed other bookings of the Vanilla Fudge for April 10 and 11 and Janis Joplin for April 18 and 19 – neither shows eventually panned out.

February 24, 1970 – Minneapolis Star Allan is quoted as saying the acoustics in the building were perfect – “despite the memories of some past bus riders of unintelligible public address calls there.” The new corporation was called The Committee, with Fingerhut acting as chairman of the board and Stevens as president.

February 28, 1970, Connie’s Insider: “Joe Cocker is booked for the opening weekend of the Depot in Minneapolis, scheduled for April 3rd, I believe. This club has got everything going for it. Admission for the Cocker opening will be $3. You have to be 21 to make the scene at the Depot. By the way, Danny Stevens assures me that the Depot will go out of its way to play new, upcoming bands, in addition to the best in local talent.”

March 21, 1970, Connie’s Insider

The Committee advertised heavily in Connie’s Insider before its first show, but not very much thereafter.

Page 30: THE COMMITTEE PRESENTS National & Local Rock Talent 6 Big Nights a week. 3 Bars; Restaurant; Boutiques; Just the beginning of the Midwest’s finest and largest Nite Club Theater. Featuring National Talent.

Page 32: HAPPINESS IS A GUY NAMED JOE! FOLLOW THE SEARCHLIGHTS APRIL 3 FOR A NICE TRIP! (Old Greyhound Depot) Downtown Minneapolis

Page 35: Fillmore Avalon, Electric Theater, and now “The Committee” Presents “The Depot,” Opening April 3 & 4 with Joe Cocker and the Grease Band … Total Kinetic Environmental Lights and Sound by Tomorrow Inc. of California * Open 6 Nights a Week * Complete Restaurant * Boutiques * Indoor Parking * Need We Say More?

March 29, 1970, Minneapolis Tribune: “A Short Wait at The Depot”

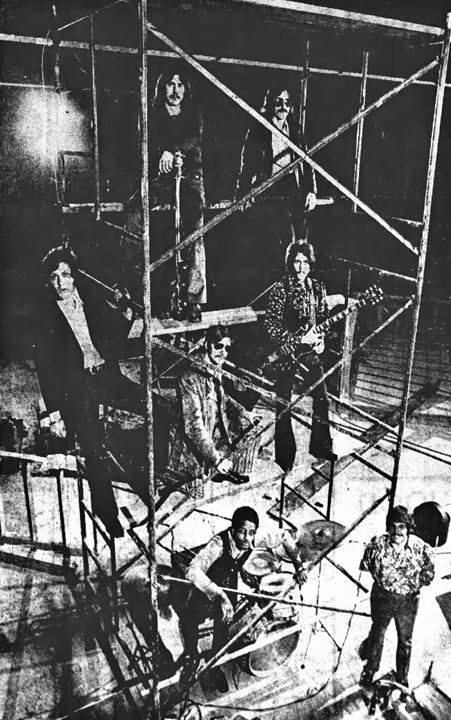

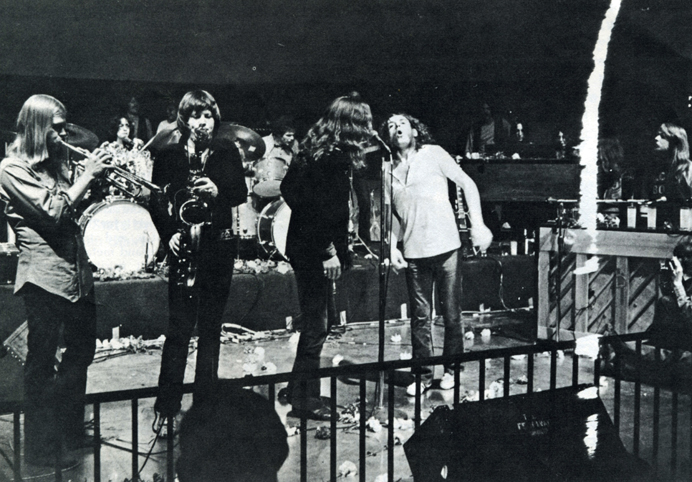

Danny Stevens, hanging in there on the left side of the scaffold, and his band, The Reasons, posed last week in the former Greyhound Bus Terminal, 7th St. and 1st Av. N., which is due to open Friday as a night club called The Depot. Stevens, president of the corporation that owns the operation, and the others appeared confident that redecorating will be completed in time.

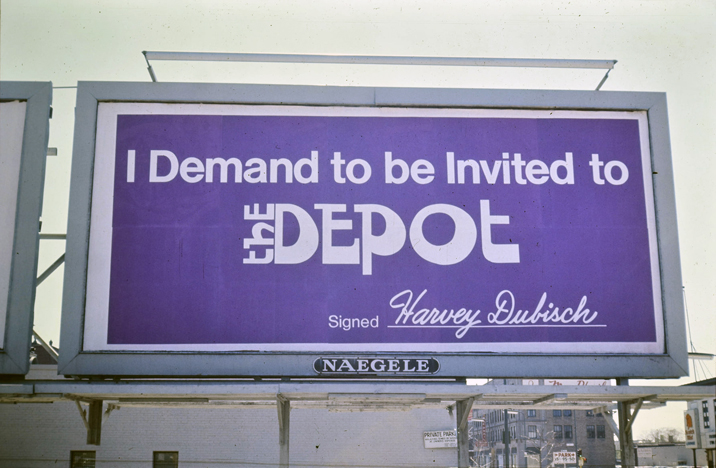

THE SAGA OF HARVEY DUBISCH

In an attempt to create a buzz about the Depot, Allan got it in his head to put up 30 billboards around town that said something to the effect that “Everyone is Invited to the Depot… Except Harvey Dubisch.” Those stayed up for about three months. As a follow-up, for a month he put up the billboards shown below, ostensibly an answer from the supposedly fictional Harvey Dubisch, demanding to be invited to the Depot.

The campaign created enough of a stir to be included in Minneapolis Star columnist Abe Altrowitz’s “View From Lake Calhoun” column on May 21, 1970. Altrowitz was enamored of a new acronym, Deleted On Grounds Of National Security (DOGONS), and named several instances where he could use it. One of them was, “The real reason Harvey Dubish is barred from The Depot is — DOGONS.”

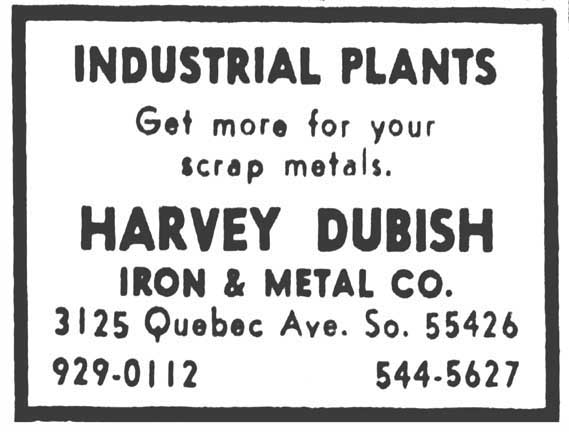

Well, the problem was that Allan neglected to check to see if there was a real Harvey Dubisch who might take issue with having his name bandied about on billboards. Close enough – there was a Harvey Dubish who owned an iron and metal company in St. Louis Park – Allan’s home town. And Mr. Dubish was not amused. In fact, Allan told me that his wife sued, and the Committee had to dig into their limited funds even further to take care of that fiasco.

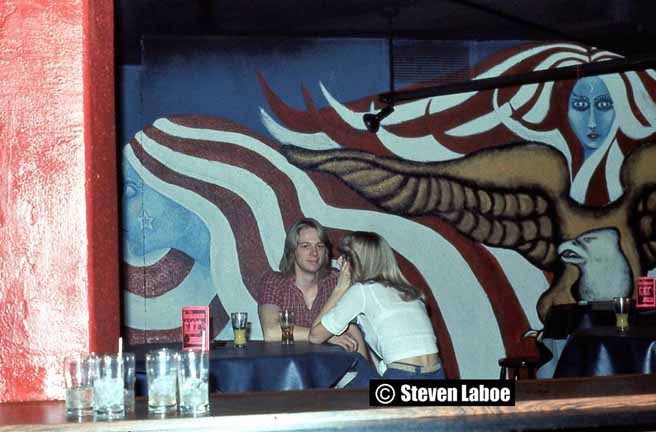

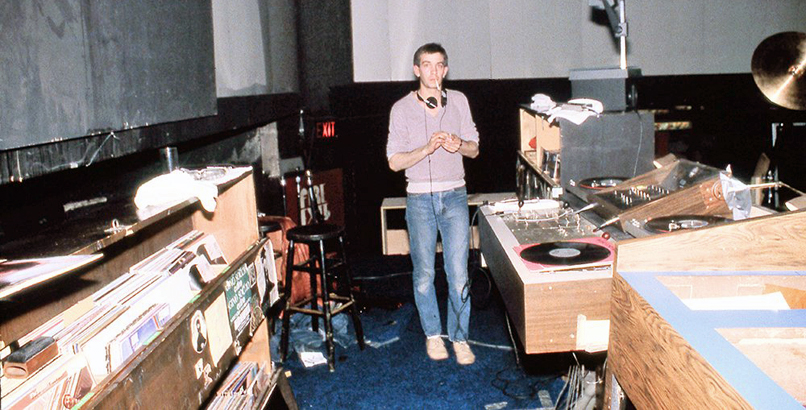

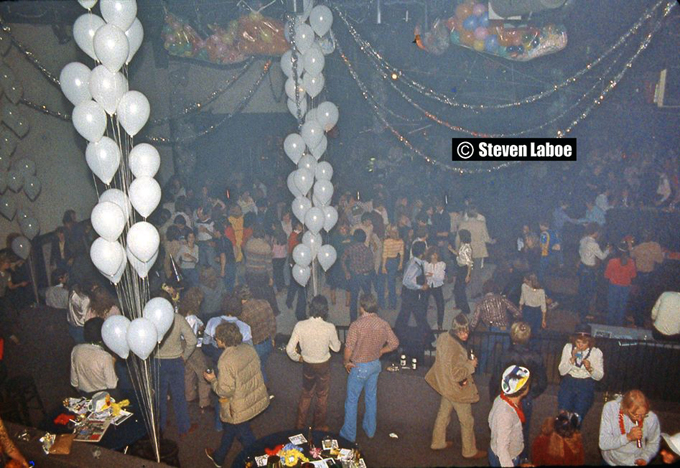

INTERIOR OF THE DEPOT

The interior was designed by John Neil, with many of the walls decorated with huge pop murals done by West Bank painters. The decor was purple, with purple shag carpet on the stage. The purple was in honor of the Minnesota Vikings, who had come to town nine years earlier.

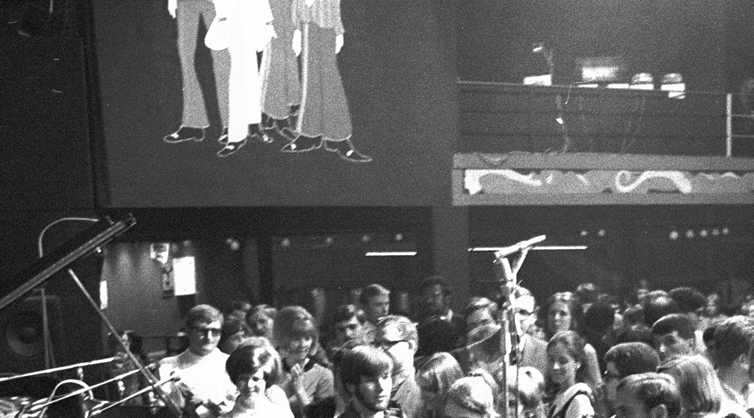

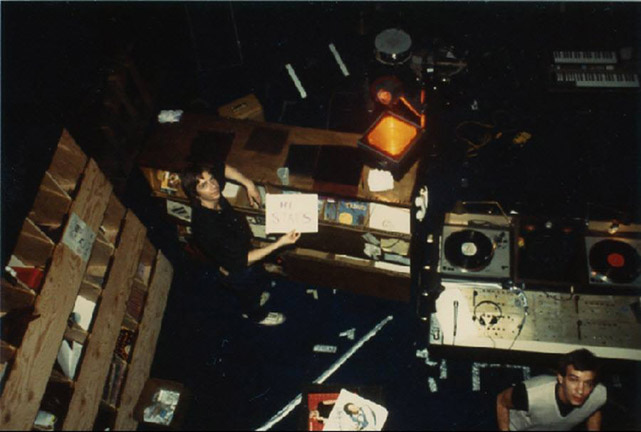

The Depot was still being hammered and sawed up to the last minute. Here’s a bird’s eye view of what it looked like in the very early days.

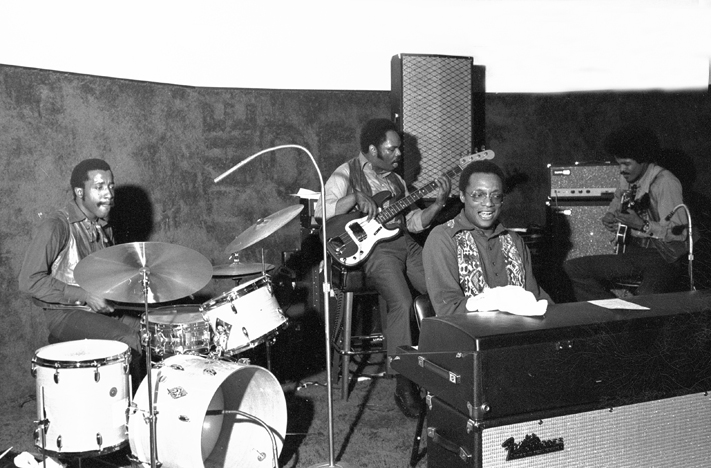

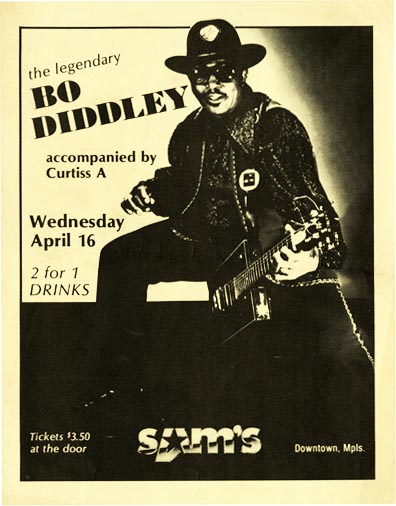

There was at least one large picture of the Beatles on the wall – the closest photo found is this one from the Ramsey Lewis show, where part of one is seen up on the balcony. Perhaps a foreshadowing of the John Lennon Tributes that take place each year on December 8, led by Curtiss A.

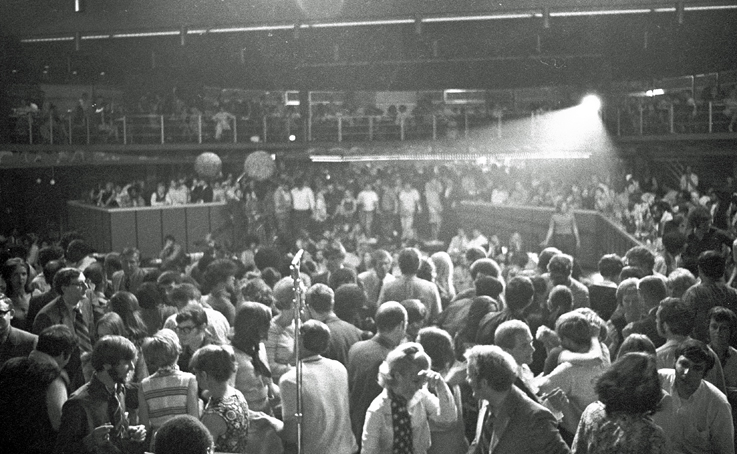

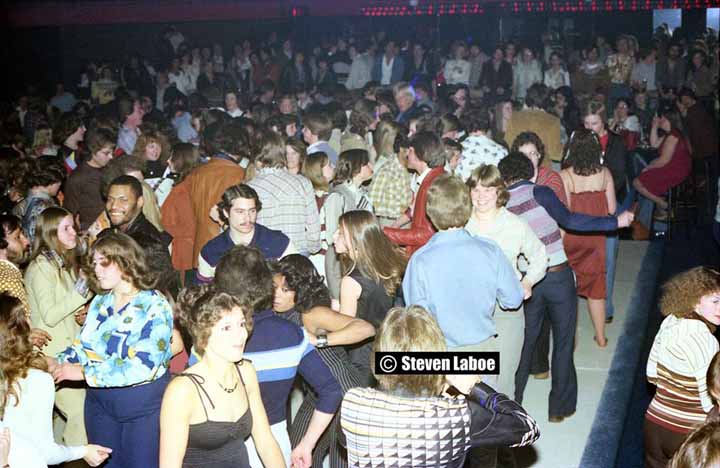

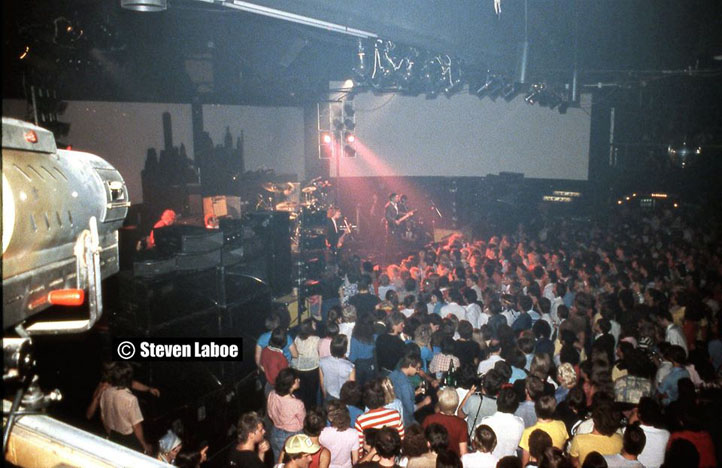

Another photo from that Ramsey Lewis Show gives us an idea of what a sold-out show looked like back in the Depot days. The round things on the left are some sort of decor.

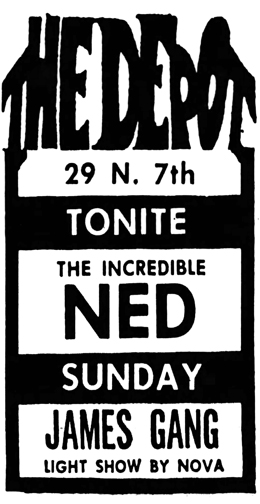

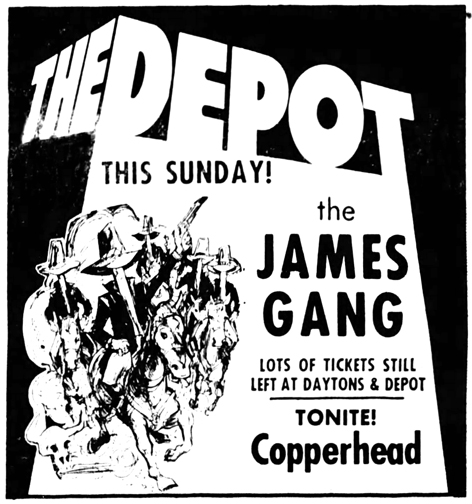

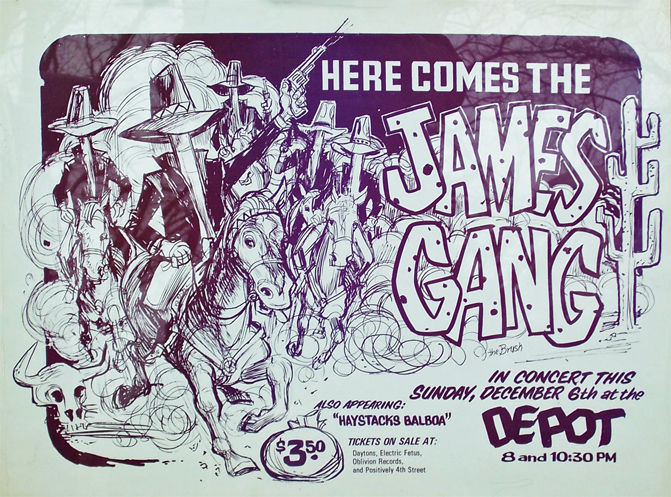

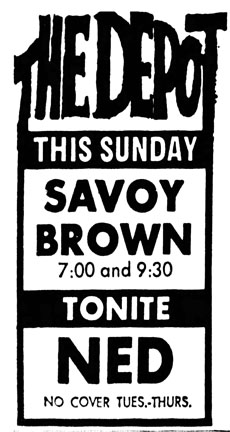

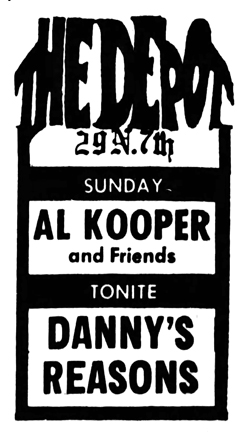

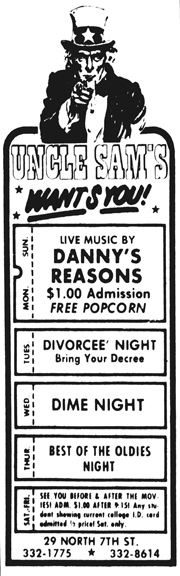

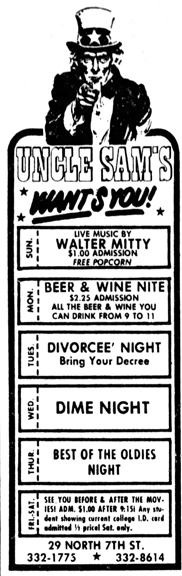

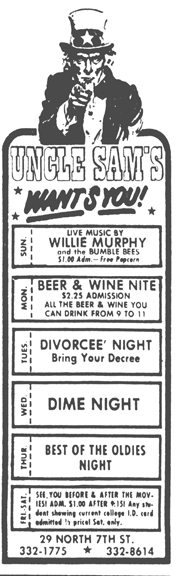

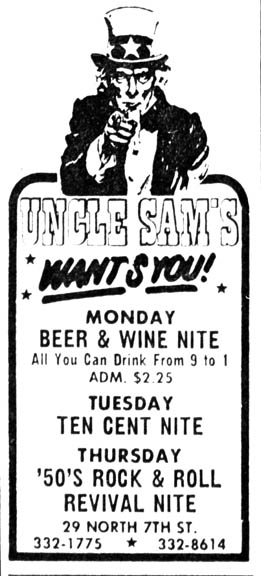

HOUSE BANDS

Although Danny’s Reasons were reported to be one of the house bands, they mostly only played Beer and Wine Nights on Mondays. (DS) Frequent house bands were more likely to be:

- Crockett

- Grizzly

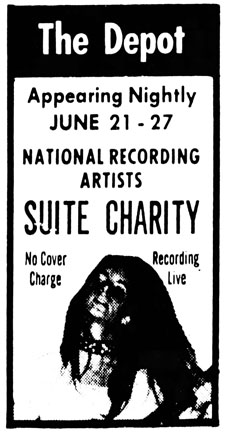

- Suite Charity

- Ned

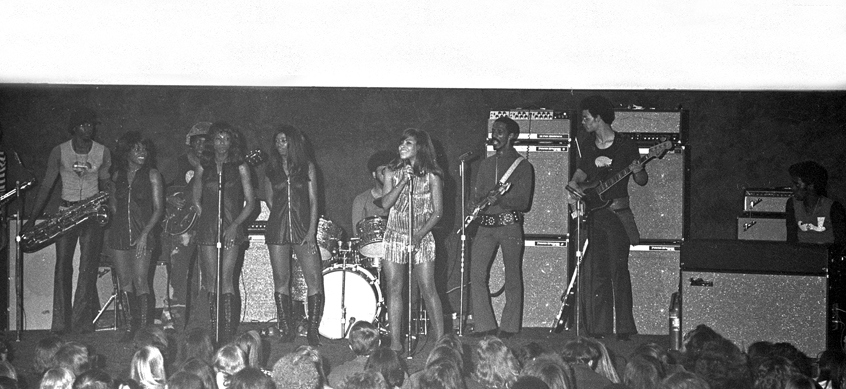

- The Sir Raleighs (who became Copperhead)

- Big Island

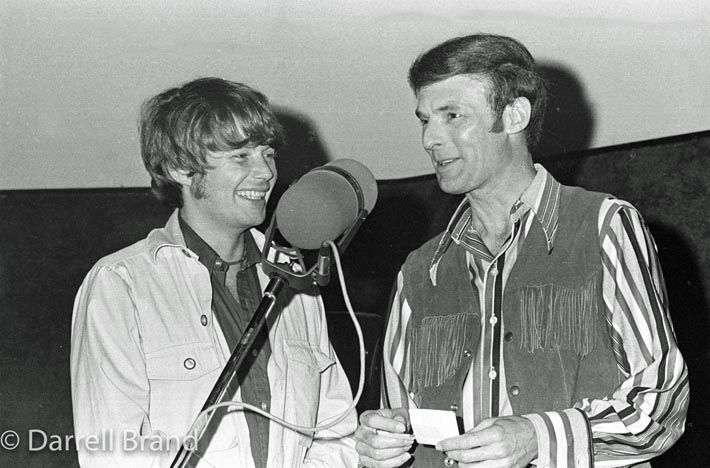

THURSDAY, APRIL 2, 1970 – VIP NIGHT

The night before Joe Cocker officially opened the Depot, the Committee held a party for the Media and 500 guests (250 + 1) to introduce the new venue. Danny Stevens remembered that Timothy D. Kehr helped put the guest list together. Film clips were taken of the new place, and TV interviews with prominent hosts such as Bill Carlson, Nancy Nelson, and Dave Moore were taped, to be broadcast after the last show on April 4 (and into late night April 5), 1970. Danny and WDGY Disk Jockey Jimmy Reed acted as MCs, and pizza was served.

Music was provided by the Paisleys, Cricket, and possibly Big Island – Danny’s Reasons and the Del Counts did not play that night.

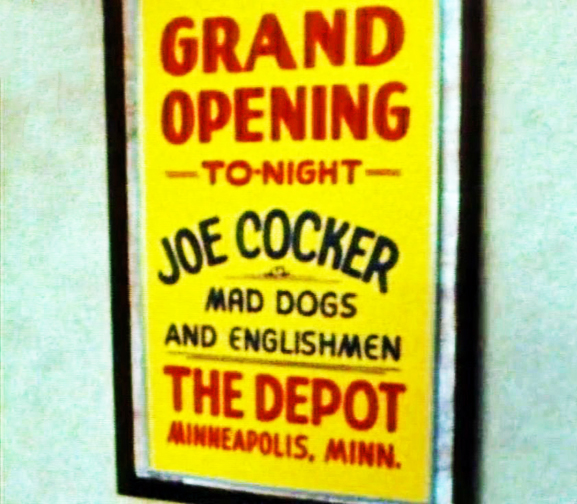

JOE COCKER OPENS THE DEPOT

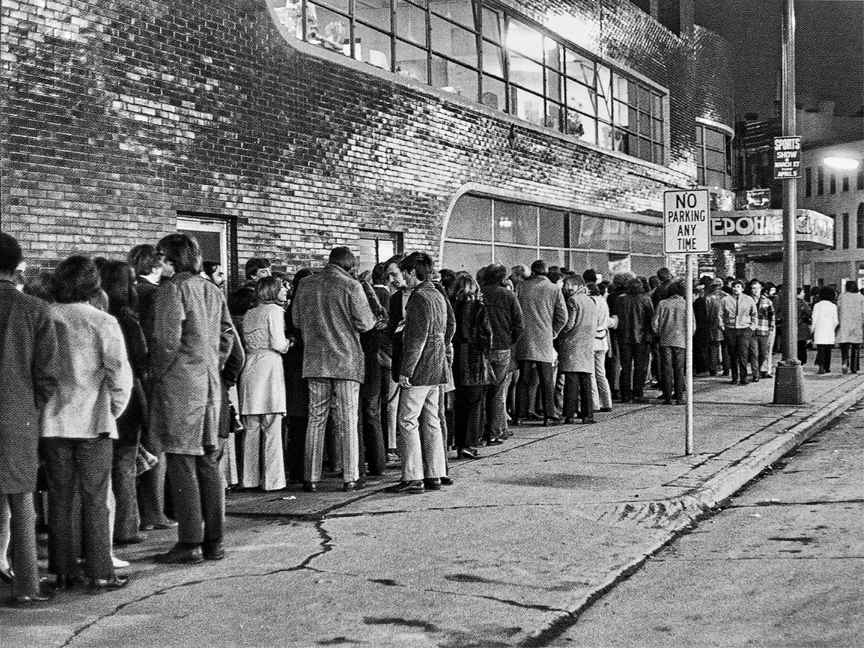

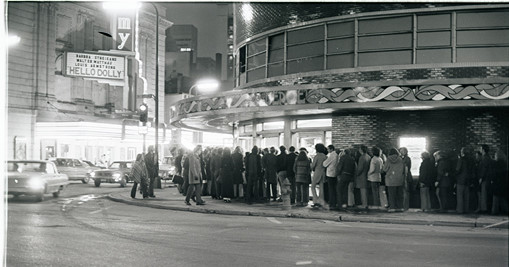

The Depot opened on April 3 and 4, 1970, and an estimated 2,300 people came to the club over the two days to see the Mad Dogs and Englishman tour featuring Joe Cocker.

A photo of the poster was found being held by Cocker himself on the night of the opening!

Let’s bullet the factoids:

- Bill Graham had helped them line up Santana for the opener but it didn’t work out. (CR)

- Leon Russell was the musical director of this American tour, which descended on 48 cities over 60 days.

- The movie Woodstock, which introduced Cocker to many Americans for the first time, had just hit theaters a week earlier, so the timing was excellent.

- Personnel included 20 musicians, another 20 Englishmen on stage just for fun, two or three kids (allegedly on acid), and characters like the Lunar Teacake Snake Man, the Ruby-Lipped Essence of Lubbock, Texas, and the Mad Professor. Here’s one of the toddlers:

- The enormous group of back-up singers was called the Space Choir. (CR) Two of the more famous members would be Rita Coolidge and Merry Clayton.

- Backup singer Pamela Polland’s fox terrier, Canina, had the run of the place, and infuriated Allan when she pooped on the stage. (CR) Here’s the dog, complete with “Cocker Power” tag.

- Tony Swan of the Twin Citian reported that Cocker was paid $15,000 for the weekend.

- Cocker’s manager demanded $7,000 more before the show, claiming that the booker low-balled the number of people expected. (CR, DS) Lawyers got involved when Cocker’s people threatened to pack up and leave, violating their written contract. When they found out that a call to the Teamsters’ Union would prevent this, the show went on.

- The Depot was the smallest venue on the tour, which had started two weeks before. (CR)

- Cocker’s people didn’t know they were inaugurating the new club. (CR)

- Allan ordered 2,000 carnations, which were thrown back and forth between the audience and the performers. (AF)

- On opening night it cost only $4 to get in, but there was a $10 charge for a table, with much poaching of seats going on.

In an interview on March 30, 2018, for Channel 5 news, Danny Stevens recalled, “Joe Cocker, I thought, was a real gentleman. I remember picking the whole group up at the airport. They came in on their own plane.”

Johnny Canton, Program Director of WDGY Radio, acted as MC for the show.

LOCAL ACTS

Thursday, April 2, 1970 – VIP Night

Danny remembered that three local bands played at the party put on for the Media and the Beautiful People of the Twin Cities, but was unclear about which ones.

Tim Emerson remembers that his band Cricket was one of them.

One of them could have been the Paisleys.

Neither believe that the Del Counts nor Danny’s Reasons were on the bill.

Perhaps the third was Big Island.

Friday, April 3, 1970 – First Night

There is a great deal of controversy about which local bands played during the two days that Joe Cocker opened the Depot. Connie’s Insider reported that local band booker Marsh Edelstein was upset that publicity about the concert did not include the bands that played before and between shows.

Many bands remember that they were the first to play at the Depot. Unfortunately, that elusive first band is not documented in any review that I’ve found. This is what we do know:

There was a “preliminary rock act,” according to Allan Holbert of the Minneapolis Tribune, (April 4, 1970).

Marshall Fine deemed the opening band “terrible.” (Minneapolis Star, April 6, 1970) When contacted in April 2023 to find out what he remembered, he replied, “Apologies. I don’t even remember there being an opening act, I’m afraid. Your search continues.”

Jim Gillespie of the Minnesota Daily called them “a trio of high school kids who probably wowed ’em at the Thanksgiving Turkey Trot but had no business playing at a place where it costs four bucks a ticket.” (April 10, 1970) The reference to youth made me think of Debb Johnson, but they had 7 pieces.

The two reviews above establish that it was a trio. One trio, Triad, didn’t move to Minneapolis until May 1970, according to minniepaulmusic.com.

A common suggestion was Crockett, but member Tom “Footie” Husting reported, “Wasn’t Crockett. We didn’t get together until after the Poco at the Depot gig.” Another member, Larry Hofmann, concurs. Besides, that band had four pieces. Crockett did go on to become the first “house band.”

Others suggested the trio Jokers’ Wild (which was called Flash Tuesday at the time), but member Denny Johnson remembered that the band was in Nebraska the entire month of April 1970.

Richard Timm says the Paisleys opened that night. But he also remembers that the Bangor Flying Circus performed next before Cocker, and that surely didn’t happen. In addition, it does not appear that the Paisleys were a trio, they were not unknown teenagers, and reviewers would have mentioned their name. Perhaps he was thinking of the night before, or the night after.

Charles Schoen says the Del Counts opened that night. For the same reasons as above, the Del Counts are unlikely. They were not a trio, they were well known, and they already had over ten years’ experience. It is very possible that they performed between shows, however.

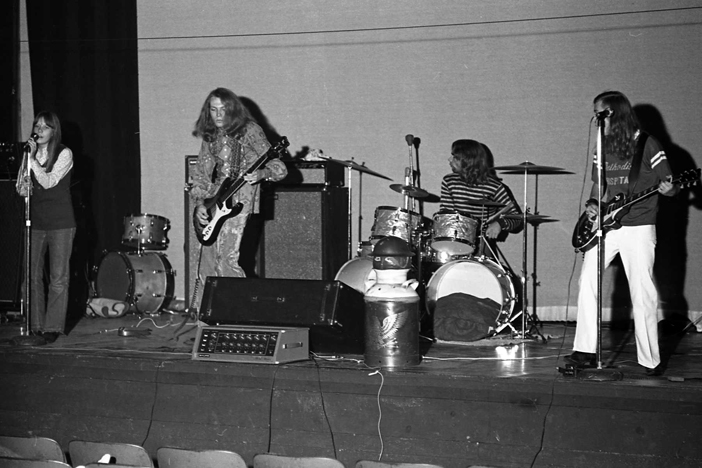

Bear, Beaver, Peacock

Will Jones and his wife lasted about two minutes at the opening before his ears gave out. The opening band was TOO LOUD. The photo below accompanied his column – it is a terrible, grainy photo, but it shows a trio.

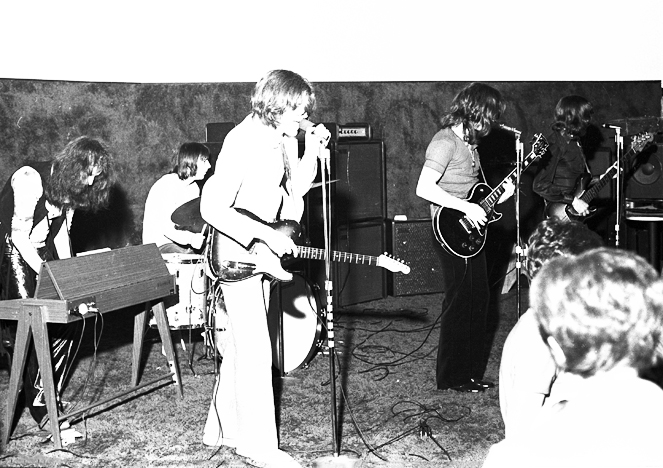

One possibility might be Bear, Beaver, Peacock. The photo below was taken on September 17, 1970. This is not very likely, however, since this was not one of Marsh Edelstein’s clients.

Steve Barich was too busy running the light show to be paying attention. Larry Loofbourrow, who was running sound and the light show, understandably doesn’t remember 53 years later.

On April 4 the supporting acts were Kaleidoscope and the Paisleys. (no citation)

Another account says that Pride and Joy performed, and Cricket was scheduled but was bumped for time. (no citation)

Please Contact me if you have any recollection of this important fact about the Depot!

REVIEWS OF OPENING NIGHT

MARSHALL FINE

Marshall Fine’s review of opening night in the Minneapolis Star was scathing, citing bad planning, expensive drinks, a long wait to get in, an opening band that was “terrible,” and the fact that Cocker’s first set was only 20 minutes long. Fine was a student at the U of M at the time, and complained that the under-21 crowd couldn’t get in. He did appreciate the “exquisite show” put on by Cocker, but said that the “audience’s response was comparable to that of an equally drunk group shouting ‘take it off’ at the Roaring 20s.”

ALLAN HOLBERT

Allan Holbert’s review in the Tribune’s was more focused on the sheer numbers of people who showed up, saying that people were lined up four-deep around the block. “Not since the truck drivers’ strike of 1934 is it likely that there has been such excitement, such chaos, such congestion, such noise just off Hennepin Av. as there was Friday night.” Allan Fingerhut said that they ran out of booze by 8:00 and had to send out for more.

Holbert’s account, which later calls the space the Fillmore Upper Midwest, says that carpeting and other interior decorations weren’t yet installed, but the old bus station was packed by the time Cocker hit the stage just after 8 p.m. Cocker worked hard on a stage filled with 40 people, “singing like a black man, which he isn’t and doing his dancing stuff like a spastic, which he isn’t either.”

TWIN CITIAN

Tony Swan’s account in the May issue of the Twin Citian said that the “beautiful people,” many wearing “Cocker Power” buttons, numbered 2,000, which was 600 over capacity. He said that the first show was a dud, with too much noise and confusion and older people holding their ears and beautiful people “with resplendent sun tans and $250 hippie outfits” more interested in checking each other out than listening to the music. But between sets “the ingredients underwent an important purge. A lot of the older people, having seen enough, went out the door shaking their heads in disbelief, their ears ringing. The beautiful people made a determined and lengthy run on the bar, lowering their inhibitions in direct proportion. And the hard core rock freaks moved in on the privileged table area, surrounding it, engulfing it.”

During the second set, “Everyone – everyone – began swaying in time to the music, which became so loud that it was beyond the audible – it was simply deafening. People began throwing flowers onto the stage and the musicians began throwing them back, strengthening the two-way process. … And Cocker kept pouring more and more of himself through those big banks of amps… until he was finished and just stood there, smiling amid all the flowers.” Fingerhut had provided the Carnations.

Swan’s article gives a detailed description of the Scene:

The curved wall which used to embrace the gates to departing buses is now the backdrop for a large, purple plush-covered stage. On the wall above the stage, Cinemascope style, there is a large screen. While the performers are wailing, batteries of projectors – in all eight carousel slide projectors, four opaque projectors and a 16-milimeter movie camera – shoot images onto the screen from either end of the horseshoe shaped balcony which surrounds the main floor. There are also colored spotlights and strobe lights – all the usual implements of psychedelia. There are five bars, three on the main floor and two on the balcony. There is a large, prime table area right in front of the stage: on opening night the tables went for 10 bucks a head, which could get to be a drag on the Depot’s income potential in the future.

MINNEAPOLIS FLAG

A reviewer named Greg noted in the April 10, 1970, issue of the underground magazine The Minneapolis Flag that what seemed like the entire Tactical Division of the Minneapolis Police Force (off duty) had been hired as floorwalkers and bouncers.

WILL JONES

Will Jones tried to cover the opening, but the sound inflicted so much physical pain that he speculated that the young people had developed leather eardrums to survive.

What’s been created there is an environment in which no creature born before 1940 can survive. …

The generation-communications gap may be entirely a physical thing, you know. I never wanted to communicate with one of these creatures more in my life than when a lush, bell-bottomed, dewy-smiling young blonde came over to me and moved her lips in a way that I knew, from experience in the outside world, meant that she was speaking to me. But the only sound I could hear was that which came from the amps. I stared at her, dumb and helpless. Maybe she thought I began to cry, but the tears that came to my eyes were as much from the smoke, I’m sure, as from frustration. That’s another thing that the sound does in places where these creatures and their favorite performers gather. It blocks the ventilating system with great globs of sound, and no smoke ever escapes a club or all in which rock music is performed, no matter how well-intentioned the architects and engineers may have been.

Jones lasted about three minutes until he and his wife escaped to more sedate environs.

CONNIE’S INSIDER

Connie Hechter’s review in his April 11 – 18, 1970, issue was evenhanded, citing both the positive and negative aspects of the venue and the show. He even reviews the other reviews. It’s a long piece, but I’d like to quote it in full.

Depot Opens With a Cocker Named Joe

The long heralded opening of The Depot, Minneapolis’ newest downtown night spot, took place last weekend, April 3 and 4, 1970, with that great white blues singer, Joe Cocker and his pop version of the Beverly Hillbillies in residence on the large, well-lit stage which workmen, working in mass confusion with great pressure to ready the joint in time, finished minutes before the overflowing crowds swelled into the club.

The reviews [of the club] in the daily papers were mixed. Some critics liked the club, but others seemed to miss the entire potential capabilities of the Depot becoming one of the great havens for entertainment in the Midwest if not in the entire country.

First off, the Depot can be the ideal night spot for rock or any other kind of entertainment. The place is big enough to hold more than a thousand customers, with seating for several hundreds. Many night clubs suffer from lack of size (you need lots of people to support the acts people want to see, as most name acts are priced in the “expensive” category). I mean, imagine a bus depot for a night club…. What could be better? Besides, the Depot just happens to be located in the heart of the downtown loop, a short block off our “great white way.”

Next, the man guiding the Depot’s operations and footing the bill for the massive decoration required, Allan Fingerhut, poured hundreds of thousands into his project, unlike some clubs which open with a bare minimum of capital and decoration. Fingerhut and his sidemen, Danny Stevens, Abby Rosenthal, Skip Goucher, and Clearance (sic) Kramer did most everything in a first-class manner. The fact that some parts of the operation did not function accordingly on opening weekend could only be attributed to a rush, rush schedule to get the doors open in time which translates to lack of planning and organization. This will straighten itself out, as Mr. Fingerhut and company, known as Allan’s Committee, are well aware of the shortcomings that took place last weekend.

So now you have a big club done up in a more-than-respectable atmosphere with accent on the mod generation, the young hip people who make things happen.

Did anyone take close notice of the superb light show and screen upon which it was reflected? It was a real, wraparound screen that does justice to the best Cinerama pavilion in town…. Not a bunch of sheets stringed together, hanging from the ceiling. Not that anything is wrong with a bunch of sheets, but imagine what it’s like to work with an honest-to-goodness screen.

The sound system is good, and the acoustics are excellent for a musical rock show. (More about this later.)

Perhaps the best thing about the Depot as far as catching rock acts within its walls is the important fact that one can buy a drink, unlike catching a show at the Auditorium or Armory etc. One doesn’t expect to buy drinks at the latter, but imagine digging an act with a cold glass in your hand (you over 21 people).

Perhaps now you can begin to comprehend the possibilities this club can provide. Not only rock shows but big bands and small circuses can perform now in downtown Minneapolis.

Many people were miffed that the opening scene was so crowded and the promised tables were not available, as people were sitting everywhere, whether or not they held tickets for tables. This situation never should have happened; monitors should have seen the $10 ticket holders and the press to their tables. But again, the schedule was so hectic that the place was lucky to get the doors open. Now that they did that, they can worry about the reservations and such, and the public will have to forgive the mix-ups experienced on April 3 and 4.

Other people greeted with shock the news that the club is off limits to the under 21 crowd. This is a shame for those in this category, but it is unavoidable, as the Depot dispenses liquor and beer.

One reviewer commented that the Depot is missing a substantial market by not allowing the kids into the shows. The management is well aware of this. However, they opened a night club with booze, and did not intend it to be a concert hall for the younger people. Perhaps they will provide concerts on weekend afternoons for those who cannot legally attend during evening hours.

There are those betting that the club will not “make it” for six months. I’m betting it will, provided Fingerhut tightens up the operation, sells drinks to the masses, and provides us with good national and local acts. He says this is exactly what is planned, so let’s get behind the Committee and help Allan and his gang in their efforts to make the joint successful.

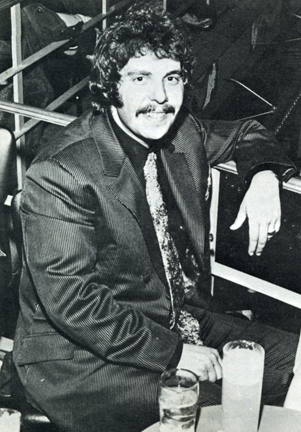

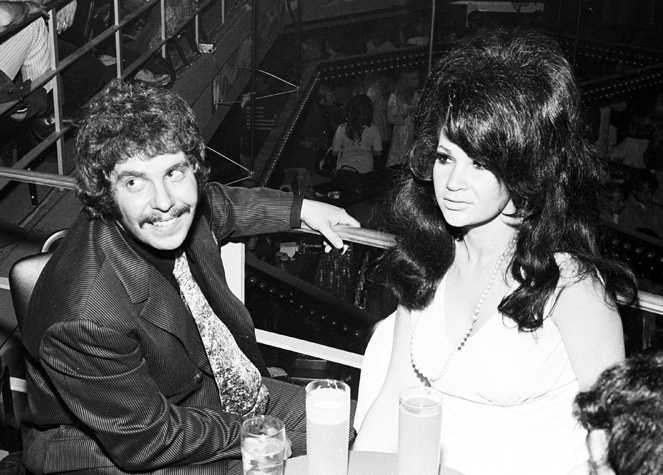

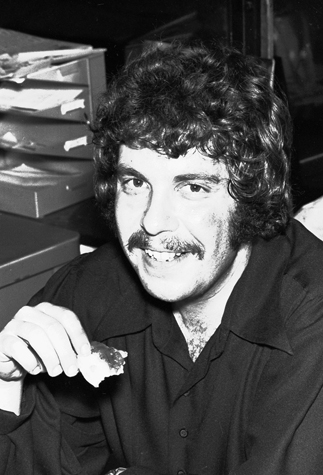

[A photo of Fingerhut bears the caption:] Cocker and his Mad Dog musicians put on one of the greatest shows of the year, so far. Allan Fingerhut, left, owner and guiding hand of the Depot, smiles as the pressure to get his club open in time is off. He was happy with the results of the club’s opening weekend. And he enjoyed the Cocker show. So did 2,300 other people over the two night stand.

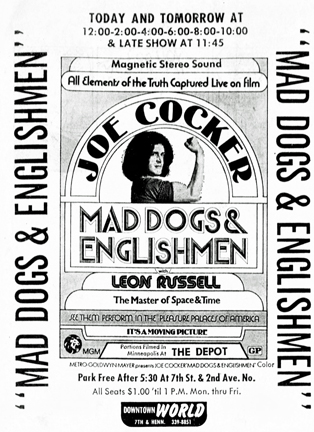

MAD DOGS AND ENGLISHMEN

The shows were filmed and appeared in the movie “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” along with other shows on the same tour.

The first time the movie came to local screens it came and went fairly quickly.

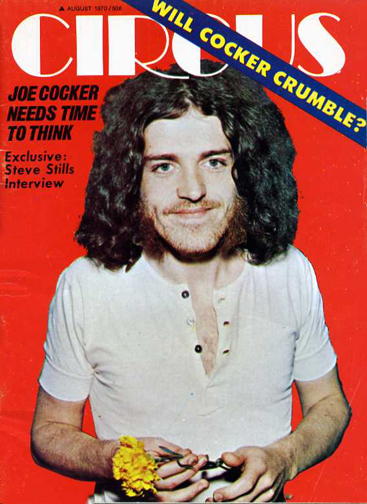

CIRCUS MAGAZINE

Mike Barich’s photo of Cocker – holding a carnation – appeared on the cover of the August 1970 issue of Circus magazine.

COCKER RETURNS

The Star Tribune, December 22, 2014, reported:

Cocker returned to the club one more time when it was called First Avenue in 1994, the same year he played the 25th anniversary Woodstock festival. However, he could not remember the 1970 gig nor the venue when Jon Bream interviewed him in 2009 before what would be his last Twin Cities area performance, at Mystic Lake Casino. He said, “The Depot? I’ll have to run it by Chris Stainton [his longtime keyboardist]. It doesn’t ring a bell at all to me.”

John Robert Cocker, known to family, friends, his community and fans around the world as Joe Cocker, passed away on December 22, 2014, after a hard fought battle with small cell lung cancer. He was 70 years old.

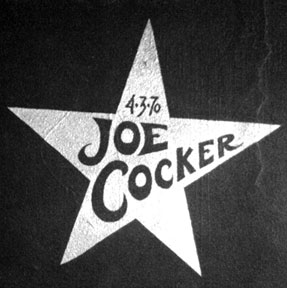

Cocker’s star at First Avenue

Cocker’s star at First Avenue

OTHER DEPOT SHOWS

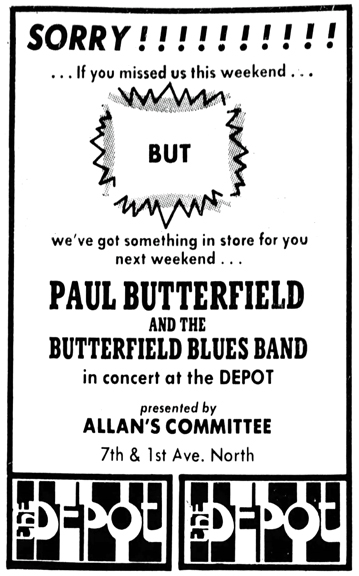

April 11, 1970: The Butterfield Blues Band (relatively small crowd)

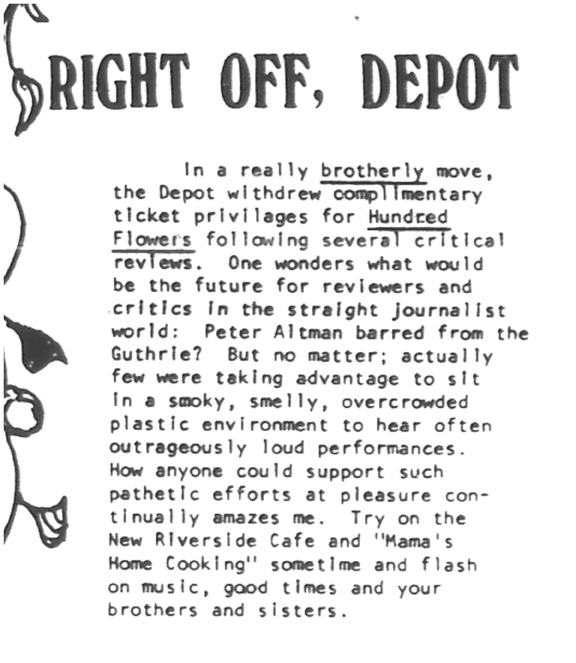

Underground newspaper Hundred Flowers had an adversarial relationship with the Depot from the start, it seems. In its April 17, 1970 issue, there was this:

the decor: amazingly tasteless

the room: amazingly tiny

the floor: amazingly crowded

the liquor: amazingly costly

the sound: amazingly loud

Cocker & Butterfield: amazing!

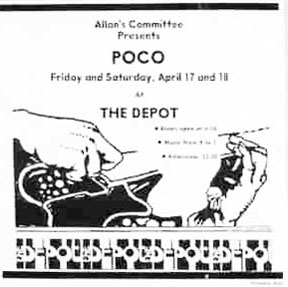

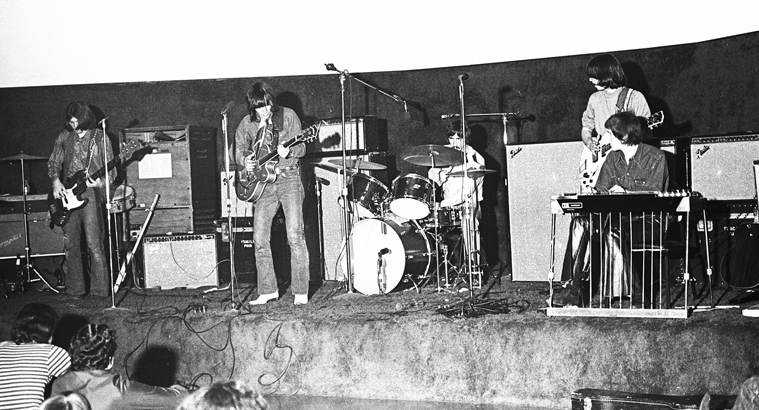

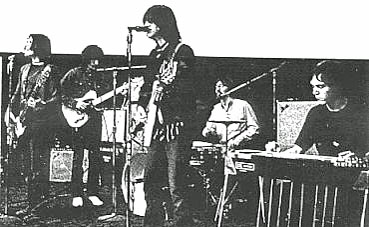

April 17-18, 1970: Poco, opened by Big Island and the Hot Half Dozen. (Crockett also remembers opening)

Richie Furay and Jim Messina, formerly of the Buffalo Springfield, made up the nucleus of Poco, and according to reviewer Marshall Fine, put on a fine show. Furay, a country music fan, made Poco into one of the first country-rock bands. They played songs from their first album and from their yet-to-be released second album. Fine had exemplary things to say about each member of the band, and headed his review “Poco show builds to stunning climax.”

Fine also had this to say about the venue itself:

The Depot, in two weeks, has mellowed quite a bit. The crowd is smaller, quieter. The whole atmosphere is calmer than when it opened. Its potential is considerable and it has turned into, generally, a pretty nice place.

Review of Poco by Ron Dachis of the Minnesota Daily:

Poco, a down home country-rock group eased into the Depot Friday night with little fanfare. But before the evening was over they had captured the small, yet receptive audience, with the ever-improving Poco sound.

From the rich sampling of new tunes we heard Friday night, especially in the second set, it appears that Poco has found itself and is well on the way to much greater success.

The bad seems to be taking more shape. It can most aptly be described as a rock band with a country feeling. The ever-present pedal steel guitar and tenor harmony produce the country effect. Hard working drummer George Grantham and bassist Tim Schmit lay down the rocking beat.

The first set started with Richie’s “Come On,” a real rocker that set the tone for the evening. Then Richie did “A Child’s Claim to Fame” for old times sake. After this number the group seemed to relax and “Anyway Bye Bye” a blues cut from their new album went really well.

“Grand Junction,” an instrumental that featured Rusty on pedal and dobro, won the crowd. Jim’s lead guitar intertwined with Rusty’s expert picking.

Next was “Consequently So Long,” “Don’t Let It Pass By,” and a new version of “Nobody’s Fool.” “Don’t Let It Pass By” featured some excellent harmonies. The new version of “Nobody’s Fool” displayed extended instrumental solos by Rusty and Jim. George and Tim were driving away while Jim came off the stage to play amongst the crowd.

They closed the first set with “El Tonto de Nadie, Regresar,” written by the whole group which, when translated means “Whatever happened to the Kinks?”

Poco returned to a somewhat warmer response for set two. This set included three cuts from the first album: “Calico Lady,” “What a Day,” and “Pickin’ Up the Pieces.” The rest of the songs from the new album were played and one thing became evident as the evening progressed. This group has found itself. The players are all doing the same things together with the same ends in mind. This singularity of purpose and tight control constitute Poco’s music.

Poco has decided exactly what they want to be doing and they’re following it through. Their new release will undoubtedly outshine the first. Poco’s development can possibly be attributed to their attitude which is much like the final song they played, “Keep On Believing.” They believe in their style, believe in their music, believe in their people. Poco made a lot of friends this weekend.

Another review, this time from Hundred Flowers: (most typos fixed)

Poco is beautiful and just what I’ve been waiting for. They’re better than ever, too. Randy Miesner, who played bass on Picking Up the Pieces, is now a gas jockey somewhere in Nebraska and Poco has made the perfect replacement. Tim Schmit’s excellent musicianship, smooth tenor voice and little brother smile fits him right into place alongside the others, already renowned for their harmonies of spirit and voice. In fact, his voice is almost indistinguishable from Richie Furay’s, who, along with bass guitar Jim Messina (lead guitar and pedal steel with Poco) was as instrumental as any Steve Stills or Neil Young in creating the Buffalo Springfield sound.

With Neil’s brother Rusty Young on organ and George Granthum on Drums, the Poco sound is just as distinctive and just as special. Their tenor voices (all but Young sing) sound like four Richie Furays or about one octave below the chipmunks and two octaves below Graham Nash.

One poster indicated the Mitch Ryder was at one time scheduled to be on the bill with Poco on April 18, 1970.

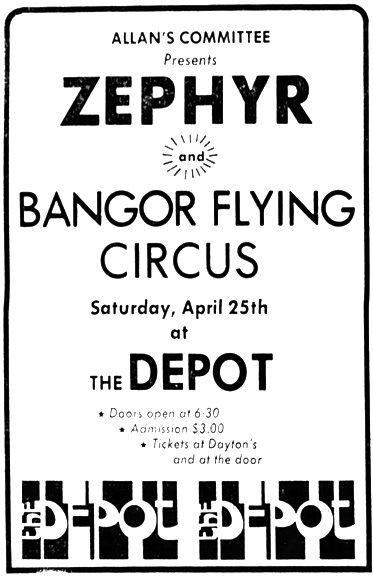

April 24, 1970: Bangor Flying Circus, opened by Zephyr

One poster gave the dates April 21 to 24, 1970 for this appearance.

The same poster showed Bangor Flying Circus and Zephyr scheduled for April 25, 1970.

Also appearing in April:

White Lightning

The New Reasons

Faith

The Paisleys

The Del Counts

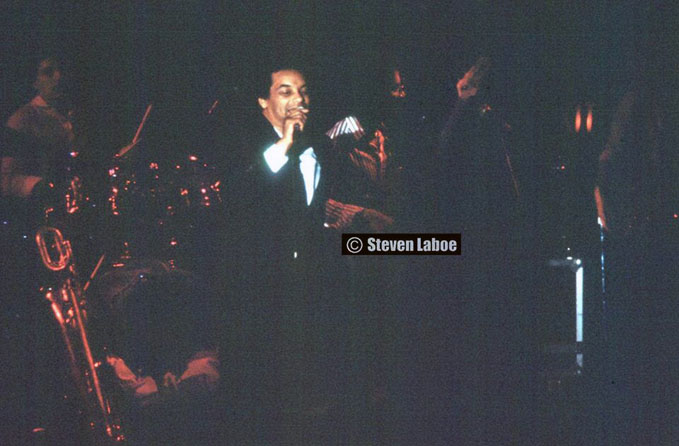

May 5-9, 1970: The Ramsey Lewis Trio. Danny’s Reasons opened on May 8. Blues Image opened on May 9.

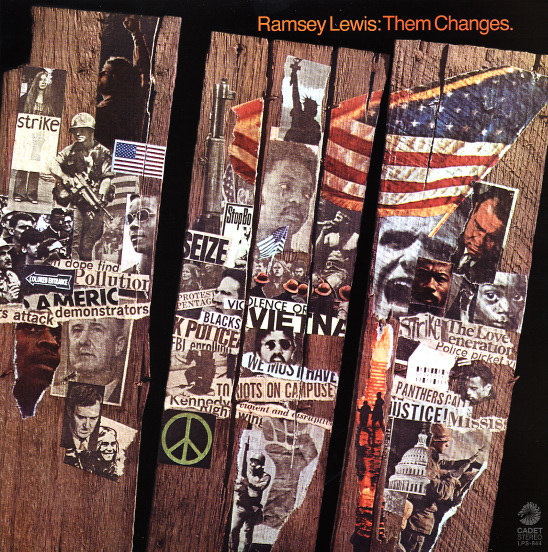

THEM CHANGES

On May 8 and 9, 1970, Lewis’s concert was recorded for his album “Them Changes,” which was released as Cadet Records LP 844 in October 1970.

Lewis alternated between a grand piano and an electric piano.

The Track List, courtesy of discogs.com:

| A1 | Them Changes | 6:40 |

| A2 | Drown In My Own Tears | 7:25 |

| A3 | Oh Happy Day | 7:10 |

| B1 | Do Whatever Sets You Free | 7:53 |

| B2 | Something | 5:15 |

| B3 | See The End From The Beginning, Look Afar | 6:15 |

| B4 | The Unsilent Minority | 3:45 |

The Credits, again according to discogs.com:

- Steinway Grand Piano, Fender Rhodes Electric Piano: Ramsey Lewis

- Electric Fender Guitar: Phil Upchurch

- Bass [Electric Fender Bass: Cleveland Eaton

- Drums: Morris Jennings

- Arranger, Producer, Concept by Ramsey Lewis

- Engineer: Reice Hamel

- Mastered by George Piros

- Artwork by Dick Fowler

- Photography by Alan Levine

- Supervised by Dick LaPalm

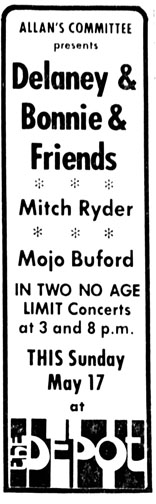

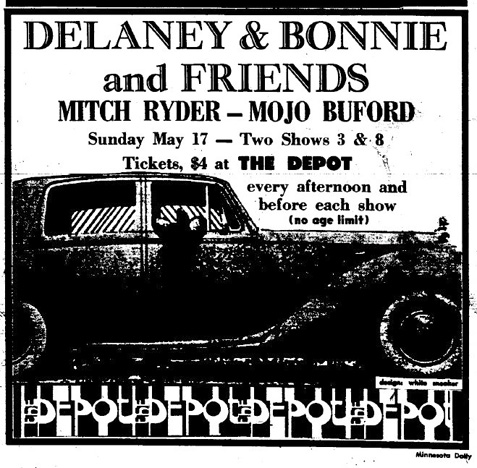

May 17, 1970: Mitch Ryder and Mojo Buford Blues Band. Delaney and Bonnie were originally scheduled to be the main act, opened by Ryder.

When Delaney and Bonnie cancelled, Ryder moved up to be the headliner. Robb Henry remembers, “Will Agar and I were the guitarists with Mojo Buford on that show. I was really impressed by Mitch Ryder’s guitarist Steve Hunter.”

Perhaps because of the substitution, there was a pretty sparse crowd.

May 22-23, 1970: Kinks, opened by Crockett. This was the first appearance by the Kinks in the Twin Cities.

There was a low turnout for the shows, reportedly, as there was a lot going on that weekend. On Friday, May 22, a “Footbridge Festival and Day of Life” took place at the U of M. This event featured David Dellinger, defendant in the Chicago 7 trial; “two mild protests;” rock bands playing on and off all day; and a free concert by Phil Ochs at 8:30 pm. (Minneapolis Star, May 23, 1970) On Saturday, May 23, a “Conference on the Black Panthers: Target of Repression” was held at the Unitarian Church.

Both the Minneapolis Tribune and Minneapolis Star reported on Friday’s show only.

Scott Bartell opened his piece with a review of the Depot itself, after the ticket taker complained that the press was giving the place a bad rap.

On the good side, The Depot has beautiful acoustics and brings in very fine groups. Even the local groups are at least pleasant. The drinks are good and not too expensive and our waitress was friendly and attentive. It is clean and, if you are going to drink, tables are a good idea – I’m glad they added more of them to their original seating arrangements.

But the atmosphere is still very much “money” and it does not make one feel warm and receptive. The freedom of rock was not in the air.

If the Kinks, the featured group, are any indication, the performers may feel the same vibrations. Their set was less than half an hour long, and was very fast and without much emphasis…

Last night they seemed to be smoother and faster than in their recordings, almost as though they were in a bit of a hurry… (Minneapolis Tribune, May 23, 1970)

Reviewer Jim Gillespie, who saw only the first show, voiced disappointment in the performance after waiting for six years for the Kinks to come to the ‘Cities. Again he noted the short first set, and said that the group did no material from its “much-touted rock opera” “Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire).” They opened with “The Last of the Steam-Powered Trains,” then the obligatory medley of their older hits. The high point for Gillespie was a tune sung by Dave Davies called “You’re Looking Fine.”

Dave’s voice is harder and more gutteral than Ray’s and eminently suitable for singing blues. His guitar work on the song was the best best he played, piercing sustained notes and staccato runs, perfectly complementing the chopped-off rhythm pattern laid down by the rest of the band. (Minneapolis Star, May 23, 1970)

And this was the first and last time we hear that there is pizza available!

ALLAN’S COMMITTEE

You may have noticed that the ads for the last six shows (starting with the second show) referred to “Allan’s Committee.” Danny, as Allan’s partner and co-founder of the Depot, was incensed at this and thought about suing, but Allan’s brother-in-law, Ted Deikel, was brought in as a mediator and worked out an agreement that the phrase “Allan’s Committee” would no longer be used. They also agreed that they would vote on all bands to be booked. (DS)

David Roth, a producer for tpt who made a documentary on the 50th Anniversary of the venue in 2020, interviewed Allan, and asked him about the “Allan’s Committee” tag on the ads, and said that Allan didn’t remember that happening.

Whatever the case, after those six shows, the phrase was no longer used.

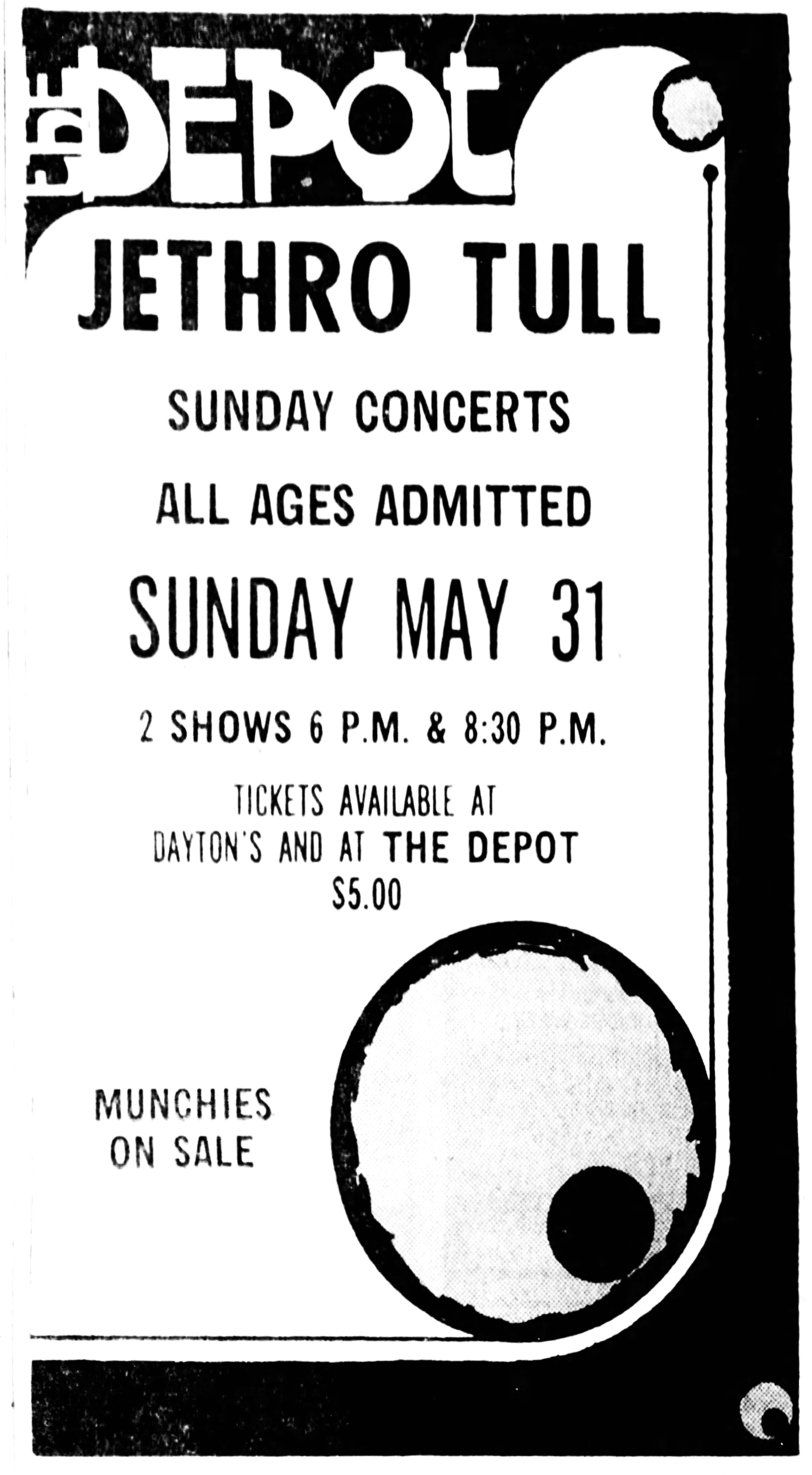

May 31, 1970: Jethro Tull, opened by Clouds

This show was open to teens under 21 – no alcohol was served. Unfortunately, the air conditioning was not yet installed, and the kids worked up quite a sweat.

Peter Altman of the Star was disappointed at the first show. Although he found the group to be outstanding, he posited that they had not become “super-popular” because they don’t stand out.

What was missing in the first set was individuality and a quality one might call repose or ease. There was little sense that the musicians had anything very personal to say. Wit was not pronounced. Solos lacked variety. There was not a great deal of attention devoted to free musical conversation. Often the musicians seemed to be playing by the book or off in their own private worlds.

Make no mistake. The sounds Tull provided were superior. The quintet has substance, and Anderson has showmanship, too. Tull played about an hour and a half and never dried up. They gave enjoyment. But whether or not they were up for their first set Sunday, they didn’t really switch on the Depot crowd of perhaps 500. There seemed to be thousands of people in line for the second show as I left the old Greyhound terminal. Maybe that inspired a really exciting session.

Ron Dachis, reporting for Hundred Flowers, was there for the second show and reported a block-long line eight people wide stretching along 7th Street, overflowing into the streets, waiting for the first show to end.

Will Shapira’s review for the Insider reported that the Depot was “pretty full” for the first set and “absolutely jammed” for the second. And the quality of the two shows were markedly different as well:

The group somehow got fouled up in its first set and never approached the heights they were to reach later in the evening. There seemed to be two main causes of their difficulty: equipment failure and a proclivity to veer away from their energizing group sound into long, boring, empty ego-trip solos. New keyboard man John Evan, lead guitarist Martin Barre and drummer Clive Bunker were all guilty; even the group’s dynamic leader, Ian Anderson, was off his form in that first set.

The second set was something else, again, however… and it was all the more remarkable because the group played the very same tunes both sets!

. . .

Jethro Tull had not only flown us into a new day and month but, hopefully, The Depot had moved us into a new period of musical experience and excitement.

The opening act was Clouds, a Scottish band touring with Jethro Tull. On this day they were also having equipment problems. Altman deemed the trio “tedious;” Dachis called Clouds “repetitious and dull.”

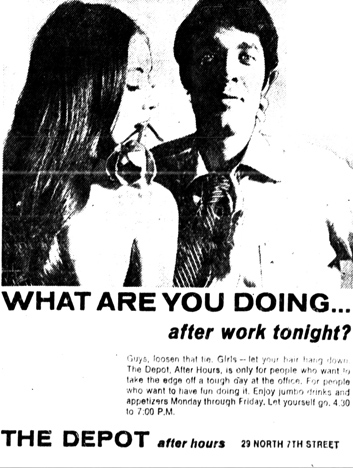

THE DEPOT AFTER HOURS

An early but apparently short-lived promotion was to target the after-work crowd and tempt them with the beautiful people they might meet at the Depot. Below, a woman eating a flower meets a local Tom Jones … This is the only ad like this I found.

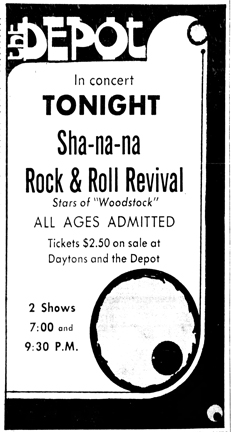

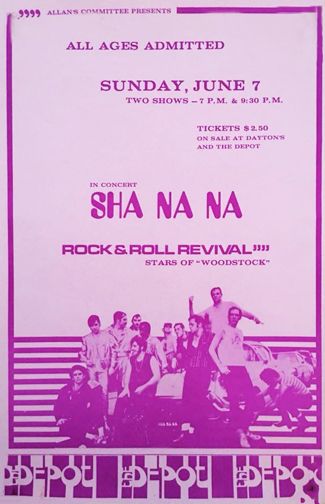

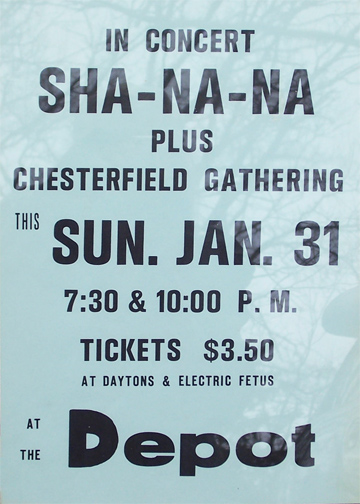

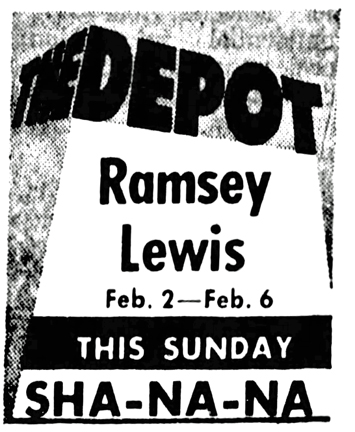

June 6, 1970. Sha Na Na made a special guest appearance (they were scheduled for the next night) and Hundred Flowers reported that the 21 and over crowd was not especially impressed.

June 7, 1970: Sha Na Na did its regularly scheduled show on teen night.

Fifty years later, someone in the audience said: “I remember distinctly Bowser saying, ‘Just one thing to say to all you fucking hippies: Rock and Roll is Here to Stay!’”

Hundred Flowers (Tom Utne?) said the younger crowed “showed the Depot what audiencing was all about.” As usual, HF had a beef, though:

Just to let you folks know, neither Sha-na-na nor anyone else gets anything extra for doing two shows. They just cut ten songs out of their regular set and do it twice. … Hasn’t the time come when Minneapolis is no longer considered a sucker-town by musicians and promoters?

Marshall Fine reported that the “audience alternately laughed at and cheered the group’s antics, were they hair combing or doing the twist.

Sha-Na-Na’s act is slick, possibly even greasy. The group spits, scowls and does its best to ape James Dean. It is more musically talented than it first appears, and also wildly funny. The humor in the group’s act depends on the ability of the audience to laugh at itself. For Sha-Na-Na is satirizing American youth as it was. Few in the crowd were too young not to remember the songs and styles mimicked. The humor could easily be misplaced. If any member had the slightest disdain for what he was doing, Sha-Na-Na’s hole thing would have come off ass too campy and the joke could have disappeared after the first song. Sha-Na-Na takes its role very seriously on stage, however, and it can create the mood that reigned in the days of the four-chord progression.

Adding to the atmosphere last night was the fact that the Depot’s air conditioning was not working. The sweaty, steamy temperature provided the decor that probably existed in the oven-like auditoriums of yesteryear.

This next part of Fine’s review needs clarification:

Danny’s Reasons preceded Sha-Na-Na and put the crowd in the mood for the headliners. Everyone was so fed up with the Reasons that they were all the more ready to hear a good group.

Danny says it must have been someone else: “We never did play with Sha-Na-Na. We only played on seldom occasions on Beer and Wine Night* and on the Gathering at the Depot album. We were never a supporting act for any of the national groups.” Danny has said that his group was not the kind of band that would fit in with the Depot crowd.

Will Shapira submitted this rather snarky review for the Insider: “Sha-Na-Na effectively recreates the popular music that nurtured the silent majority that made up the Silent Generation.” And this: “The years of the ’50s that I devoted to jazz were all the more well-spent upon rehearing “At The Hop” and the other delights of that era.” Guess he didn’t like it.

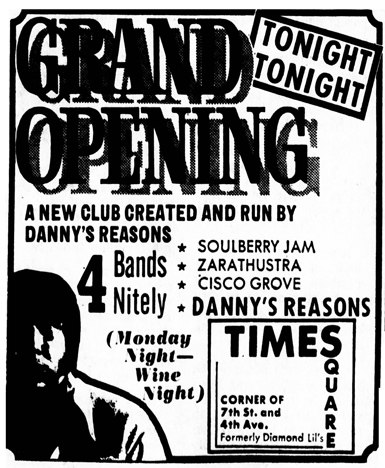

* Beer and Wine Night was a continuation of a promotion Danny had used at his previous club, Times Square. For $2.50 (men) or $1.50 (girls) (sic), you got a plastic cup at the door, and between 9 and 11 pm, you could have all the beer or Bali Hai or Reva wine you could drink. Danny noted that Beer and Wine night was especially popular with professors from the U of M.

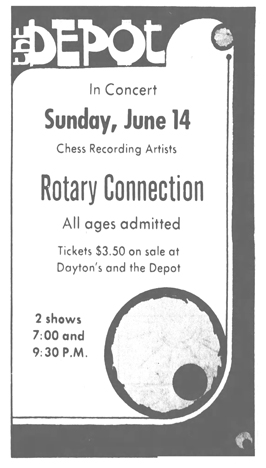

June 14, 1970: Rotary Connection with Minnie Ripperton. Opened by Thundertree.

Reviewer Jim Gillespie, a student at the U, reported that the seven-piece group with two lead singers had an instant rapport with the audience. Apparently the world was not aware of the charms of Minnie Ripperton: “Most of the time the girl sang along in a screamingly high pitched voice, at times creating the effect some groups obtain by using an electronic instrument called the theremin. Her range was amazing and she added much to the total sound of the music.” Songs performed included:

- Sunshine of Your Love

- Ruby Tuesday

- Stormy Monday Blues

- Soul Man

Gillespie was impressed with local band Thundertree, remarking that they were better in person than on their record, they played several interesting original songs, and their version of “16 Tons” was “really stunning.”

In the Insider, Will Shapira’s review noted that Ripperton’s voice was “super-shrill” last year at the Labor Temple, but that it had improved its sound and were much more musical, listenable, and professional. Minnie’s two-year-old son Marc impressed Shapira with his drumming and high-fiving skills.

June 20, 1970, Connie’s Insider:

Allan Fingerhut, owner of the Depot, has had some wild scenes running this big, new club in downtown Minneapolis. For instance, it cost him $5,000.00 out of his pocket to pay off the Cocker people on opening night because the club’s booker, no longer the club’s booker, misrepresented the gross potential of The Depot to Cocker’s management. Had Allan known this, he never would have agreed to the contract.

The Depot has NO cover charge during the week or on Saturdays. Only cover is charged on Sundays when a national act is on stage, and then it’s a minimum.

The Depot is making an all-out effort to fill the music gap created when the Labor Temple rock series ran into financial troubles and was forced to close a few weeks back.

On May 31, The Depot launched its “open” concert series by presenting Jethro Tull and Clouds in a pair of concerts. An open concert simply means that people under 21 are admitted and only soft drinks are served to comply with the liquor laws.

The price, by the way, was $5 a head and in this super-aware city which launched a boycott of the Crosby-Stills thing and its $10 top, acceptance meant a lot.

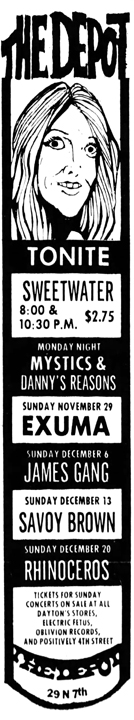

No-alcohol Sundays turned out to be the most popular nights, especially since the Labor Temple closed. These were the nights that nationally-known rock groups were brought in, with tickets selling for as much as $6.

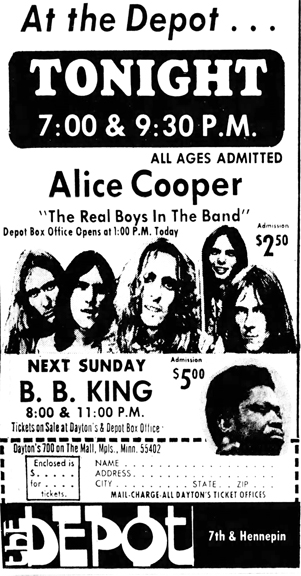

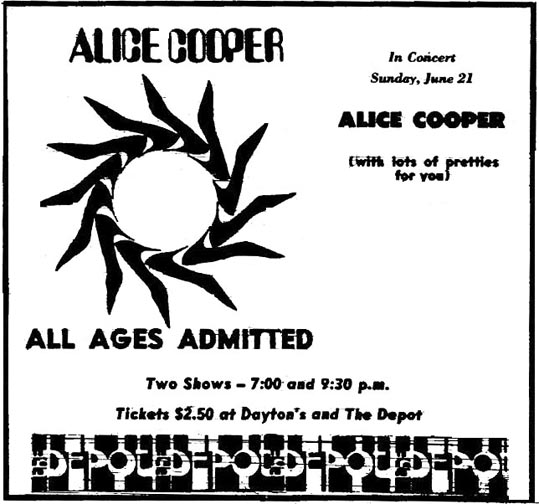

June 21, 1970: Alice Cooper, opened by Suite Charity?

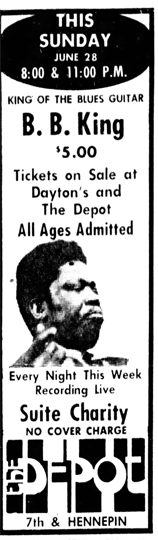

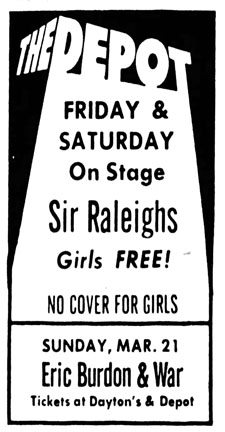

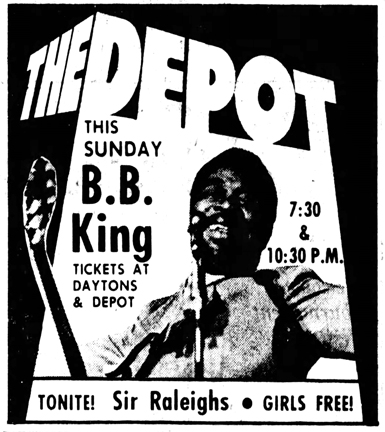

June 28, 1970: B.B. King, opened by Lazy Bill Lucas and Mojo Buford’s Blues Band. Crockett, local/house band, may have also been an opening act.

Jim Gillespie’s review of B.B. King in the Star is worth repeating in full:

The Depot was a blues freak’s paradise Sunday night as it presented three fine acts including the incomparable “crown king of the blues, the man himself, B.B. King.” And B.B. is the King, make no mistake about it.

Lazy Bill Lucas, a transplanted Chicago blues pianist now living in town, opened the concert with a short set of traditional songs in his old-time boogie woogie style.

Mojo Buford’s Blues Band then took over and played a fast-paced set of city blues like “Five Long Years” and “Messin’ With the Kids.” Mojo’s harp playing was fine, as usual, and his new back-up group, while sounding a little ragged in spots, was more than adequate.

Then came B.B.’s back-up band, Sonny Freeman and the Unusuals. The band is made up of two saxophonists, a bassist, drummer, pianist and trumpeter. They opened with a heavily jazz-flavored instrumental which featured solos by everyone in the group. Then the King walked on stage to appreciative applause and yells from the near-capacity audience.

With the first knife-sharp notes wrenched from his guitar, it was clear that we were in the presence of one of the masters. King can wring more emotion out of those six metal strings than practically anybody else in the world and that includes his big-name disciples like Mike Bloomfield and Eric Clapton. It’s all the more impressive when you realize that he invented this style almost single-handedly, more than 20 years ago.

But King’s talent is not limited to the guitar. He is also one of the finest blues singers alive, with a powerful voice and a range that extends all the way from a low-down growl to an exquisite falsetto imitation of a woman telling off her man.

The Depot is not the warmest house in the area but King’s amazing stage presence, fine sense of humor and consummate musical ability transformed it into an intimate, friendly place overflowing with good vibes.

A lot of performers don’t seem at their best in Minneapolis because they can get away with playing a sloppy set and still receive the obligatory standing ovation.

But King is one of the finest showmen in the business and he works hard to make sure everyone has a good time. And they did, too. The next time B.B. comes to town, be sure not to miss him. It’s a are and pleasurable experience.

Memories from Robb Henry:

I was playing guitar with Mojo Buford in 1970 and we were fortunate enough to be the opening act on this show at the Depot. We got to meet B.B. King and hang out a bit in the upstairs dressing room. I was 17 at the time and really impressed by how nice and friendly he was. He was one of the few guitar players that ever sent a shiver down my spine with one note, that vibrato.

When we were hanging out at the Depot, there was a woman in the dressing room and B.B. couldn’t recall her name so he discreetly told his valet to introduce himself to her so he could hear her name again. Dick Garrison and I got a big kick out of that slick little scenario. Etiquette lesson from the King.

Sharron Fingerhut Grohoski remembered that Mr. King was in awe of the scene and humbled at the adolation he received.

Will Agar:

I still remember that evening at the Depot when, half way through his show, [King] took an intermission in the second floor dressing room. There as a knock on the door and a man came in with a suitcase. He opened it and it was full of cash-payment for the evening’s work and insurance that B.B. would finish the second half of his performance!

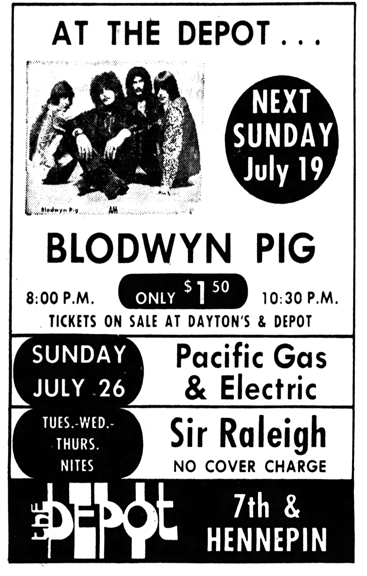

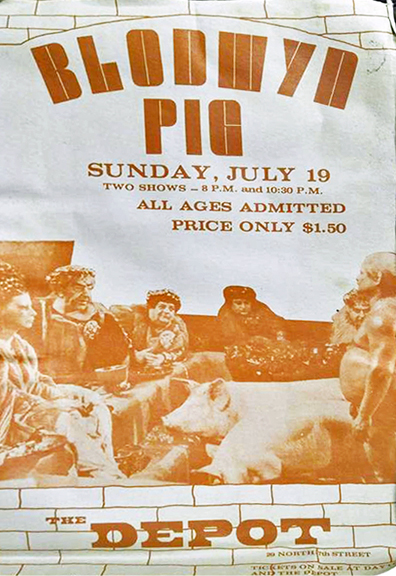

July 19, 1970: Blodwyn Pig, a British group

Always kvetching about ticket prices, Hundred Flowers announced that “the Depot is trying its damndest to relate to the community Sunday night by down-pricing tickets to $1.50 for Blodwyn Pig. Blodwyn Pig probably has the ugliest album covers in the world but there’s a lot of beauty between those covers. Mick Abrahams is the leader and former lead guitar for Jethro Tull.”

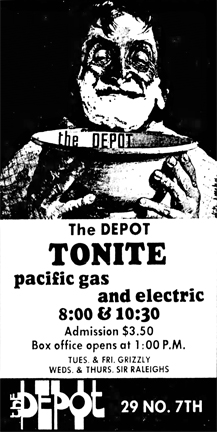

July 26, 1970: Pacific Gas & Electric. This was the group’s fourth visit to the Twin Cities, and much of the personnel had changed.

Will Shapira reviewed the show for the Insider, and reported “two sizzling sets of blues and boogies.” Personnel included:

- Charlie Allen, lead singer (original member)

- Ken Utterbach, lead guitar

- Ron Woods, drums

- Frank Petricca, bass

- Brent Block, rhythm guitar (original member)

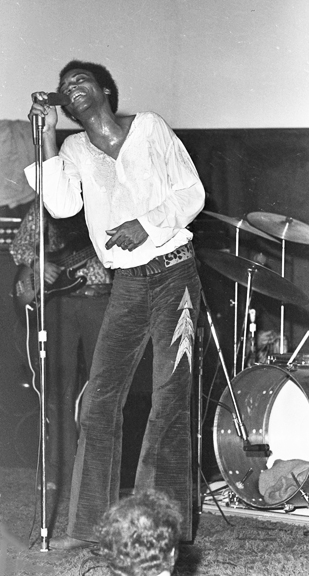

Shapira also reported two “bummers” that night. The first was a female Jesus freak who dragged everybody down with a hysterical harangue just before the second set. The second was a cop who manhanded a kid whose dancing displeased him. Charlie Allen stopped singing, told the cop to let the kid go, Charlie resumed singing, the kid resumed dancing “and everybody got it on again.” (Insider, August 29 – September 12, 1970)

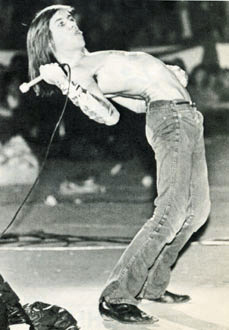

Mike Barich’s photo below shows the enthusiastic (and shirtless) patron in the throes of ecstacy.

According to Hundred Flowers, the group “didn’t play anything familiar – not even their new single, ‘Are You Ready.’ Their format is free and fast with lots of improvising, blues cliches, and revolutionary commentary.”

Maybe the reviewer from Hundred Flowers left early, because according to Dodd Lamberton’s review, “Are You Ready,” the group’s one hit wonder, was the last song in the first show, and the only one that was worthwhile. More from Lamberton, a music student at the U at the time:

PG&E’s music is mostly fast, driving blues, which can be an exciting idiom. Rock musicians rave about the magic quality of the blues that makes it so great to listen to and to play. But if the performers do not control themselves, numbers can stretch into 20-minute studies in boredom, with drawn-out solos by each member of the band… The group was capable of much more than it produced and the crowd knew it.

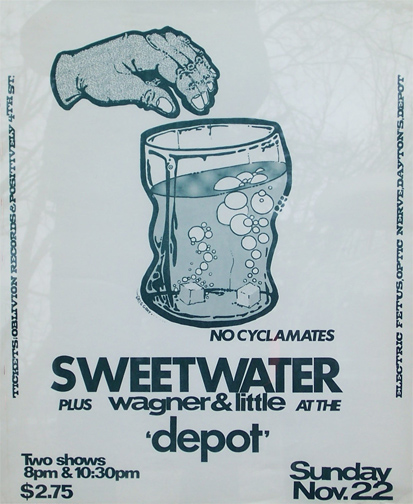

The opening band was Wagner and Little, a four-piece group from Chicago that had been playing together for only a week.

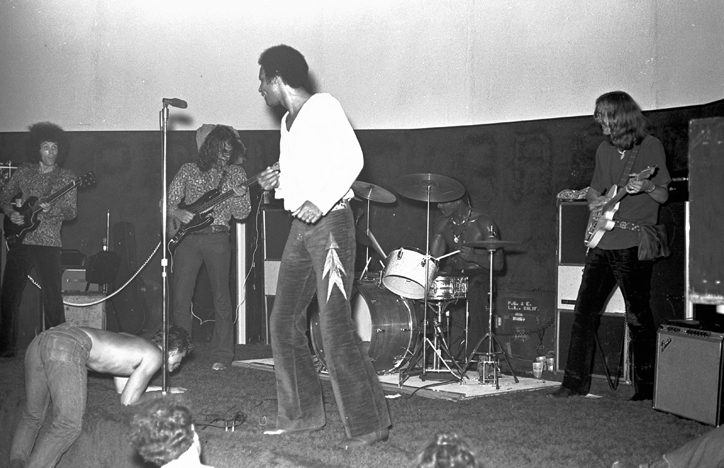

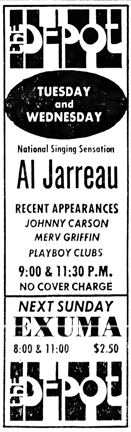

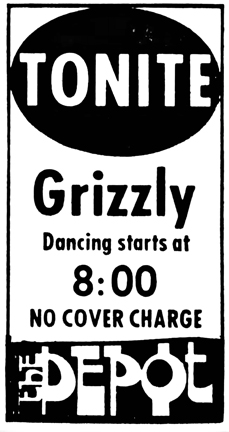

July 28-29, 1970: Al Jarreau. July 28 opened by Grizzly; July 29 opened by the Sir Raleighs. Grizzly was formerly known as Albert Hall, and the Sir Raleighs became Copperhead. (Keep up!)

July 30, 1970: Sir Raleighs

July 31, 1970: Grizzly – “The Funky Stars of the Pan-Am Rock Festival,” read an ad the day before!

August 2, 1970: Benefit for the Minnesota Eight and North Country Freedom Camp.

Tom Utne in the August 7, 1970, issue of Hundred Flowers said that bands included:

- Hundred Flowers Surfjazz Band Orchestra

- Jave, with Greg Gilmer and Rocky Melina

- Betty Boop

- Spider John Koerner

- Bamboo (Dave Ray, Donicht, Animal, and Animal’s little brother)

- Jam by Bamboo and Friends: Maurice, Tommy Ray, John Beach

The ever-irreverent HF reported that Danny Stevens

digs the scene and suggests more at the Depot, where only biweekly shows are planned for the fall. Allen Fingerhut, however, was quite pissed, does not like us not having cops at the door. Does not like twelve year olds smoking dope in his bar, and does not like our admittedly irresponsible planning. Sincerely Apologies Allen. Let’s do it again, okay?

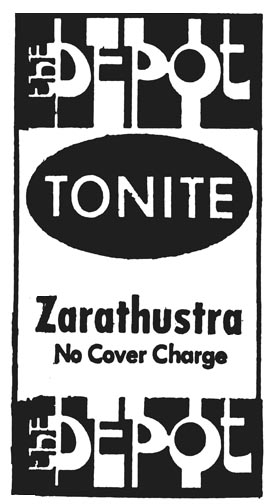

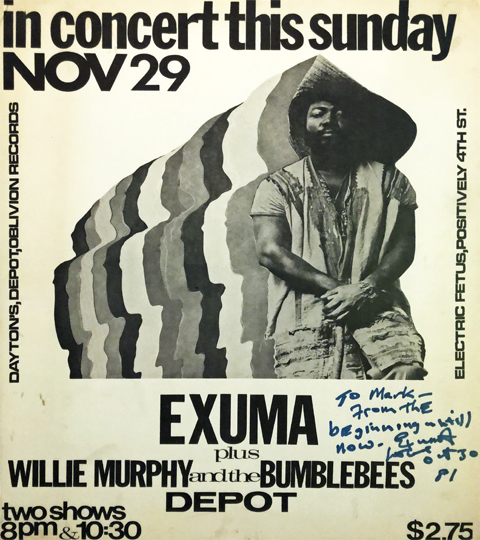

August 16, 1970: Exuma, opened by Zarathustra (first show) and White Lightning (second show)

The Trib’s Mike Steele attempted to prepare Minneapolis for Exuma, nee Tony McKay, a/k/a the Obeah Man, in an article on August 9, 1970. Steele described him as

a strange mixture combining heavy, primitive rhythms, ecstatic use of drums, a pulsing Caribbean beat, electric instruments, and a rock vocal presentation that soon becomes primitive chants.

Exuma is originally from Cat Island, Bahamas, but he came to Greenwich Village in 1961. His first album was overseen by his friend and producer, Daddy Ya Ya, with backing by the Junk Band. …

Exuma denies a connection with voodoo, but many claim that the connection is there. Exuma says only that he writes his music during seances. His lyrics are heavy on zombies, dead men, ghosts, devils and angels.

It all sounds weird, but otherwise serious men who have spoken to Exuma believe it all. His record is curiously successful. His first live appearance here should be one of the more interesting events of the year.

Reviewer Dodd Lamberton described the band as a group that defies description.

Their music brings together primitive chants, moaning and wailing, and a large variety of rhythms and instruments, including a bass drum, congo drums, whistles, bells and tamborines. It has a refreshing freedom to it, as the members of the group do not seem to have prescribed notes to sing and play – each performance is different. Exuma sings the verses of each song and the rest of the group joins in on the choruses. … In both shows, they had the standing-room-only crowd clapping and dancing to the catchy Caribbean beat. “Obeah Man,” their best-known song, was their best offering.

Will Shapira’s review for the Insider expressed disappointment in the live performance in comparison to Exuma’s first record. He explains,

What goes on in a typical Exuma set is a series of exhortations and incantations to the dark gods of the nether world, shrieked and wailed by the hoarse-voiced Exuma over pulsating Afro-Cuban rhythms. It CAN get pretty exciting at times, but not often enough, I’m afraid. (Insider, August 29 – September 12, 1970)

Both Lamberton and Shapira had great things to say about local band Zarathustra, which was booked through August 21. Lamberton called the band “outstanding,” saying that Dick Hedlund on bass, Rick Dworsky on organ and Bobby Schnitzer on guitar are “unparalleled on the local scene.” Shapira said “There was excellent vocal, lead guitar and mouth harp work throughout the set and outstanding arrangement of a song called “White Bird.” It’s a Beautiful Zarathustra!

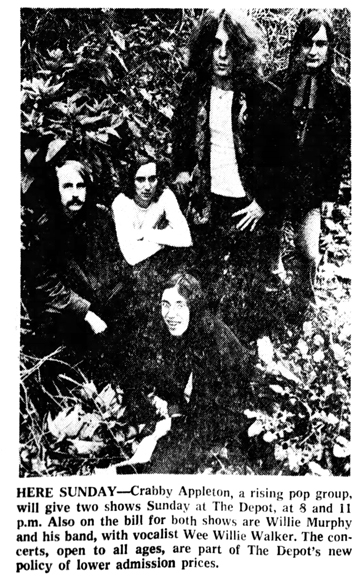

Don’t know what happened to Crabby Appleton. Maybe they had to “Go Back” to Los Angeles.

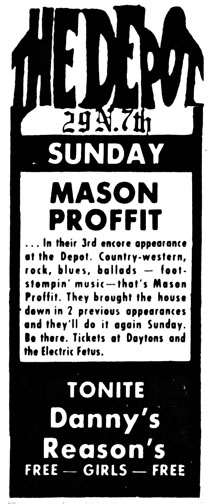

August 30, 1970: Mason Proffit, opened by Willie Murphy. This was a last-minute substitution for Crabby Appleton, which had been advertised just four days beforehand.

Reviewer Dodd Lamberton referred to Mason Proffit as the group that “saved” the Iron Butterfly concert at the Minneapolis Auditorium a few months back. Here at the Depot, “they really turned on the crowds with their smooth, country-western sound.” Unique aspects of the group were that they tuned their instruments one-half step higher than normal, and they used a dobro as a kind of fourth voice.

Lamberton also commented on the opening act:

Willie Murphy and his band made up for their disorganized appearance at the Guthrie two weeks ago with two acceptable sets of mostly original songs. Of these the best was Murphy’s “Eyes of Temptation.” The group’s sound resembled that of the original Electric Flag on the blues tunes.

And as for the Depot’s light show, Lamberton thought it was “as imaginative and as effective as any local show seen recently.”

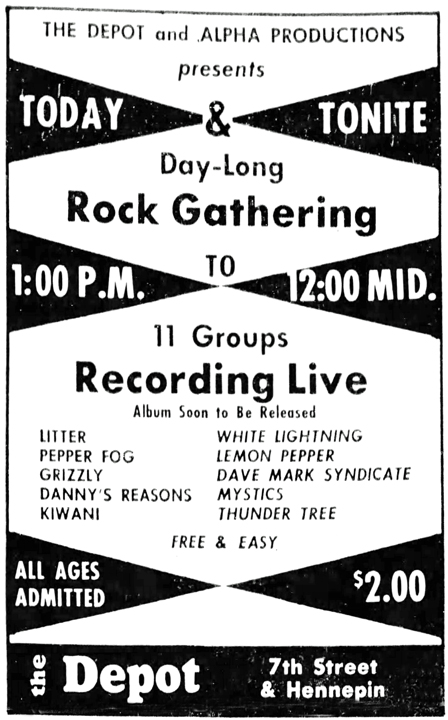

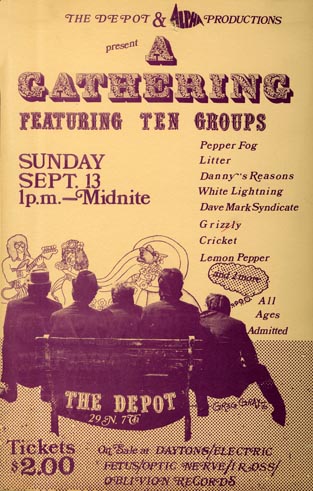

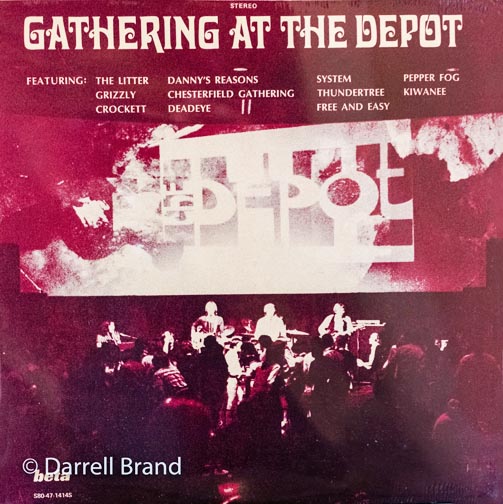

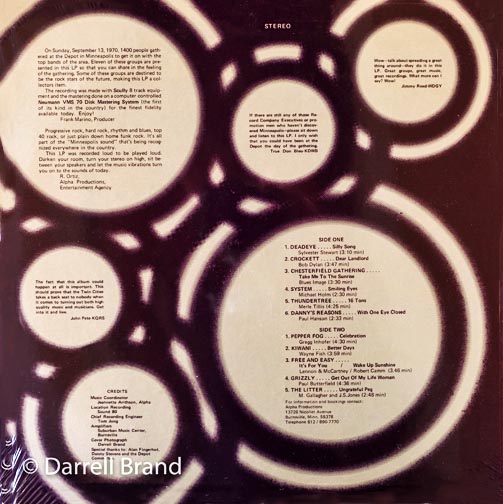

September 13, 1970: Gathering at the Depot

ALPHA PRODUCTIONS

The Gathering was a day-long event that resulted in one of the Twin Cities most sought-after albums. All of the bands were clients of Alpha Productions, and was organized by Ralph Ortiz, the head of the agency, to showcase the clients in his stable. It was originally seen as a promotional item, to be sold at the shows of the bands on the record. If a school booked one of the bands, it could sell the records at $1 profit each. The liner notes say that 1,400 people stopped by the Depot that day to hear some of the best bands in the area. Eleven of these bands appeared on the album, although more played that day.

PRODUCER

The Producer of the album was Frank Marino. For you equipment buffs, Frank reported that the recording was made with Scully 8 track equipment and the mastering was done on a computer-controlled Neuman VMS 70 Mastering System (the first of its kind in the country). Amplifiers were provided by Suburban Music Center in Burnsville.

MUSIC COORDINATOR

Jeanette Arithson was a 21-year old booking agent for Alpha Productions.

LOCATION RECORDING

Recording was done by Sound 80, engineered by Sound 80’s Chief Recording Engineer, Tom Jung.

ARTWORK

The front and back artwork was done by photographer Darrell Brand.

In addition to the people above, special thanks were given to Alan Fingerhut and Danny Stevens of the Depot.

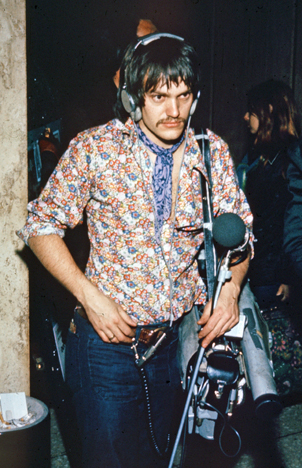

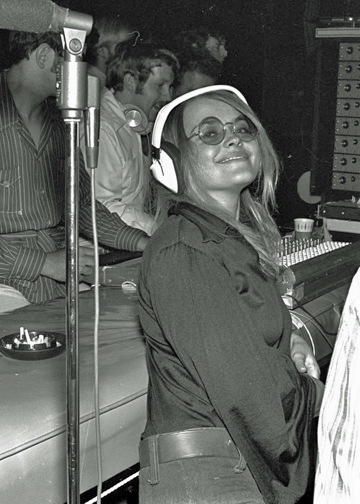

THE JOCKS

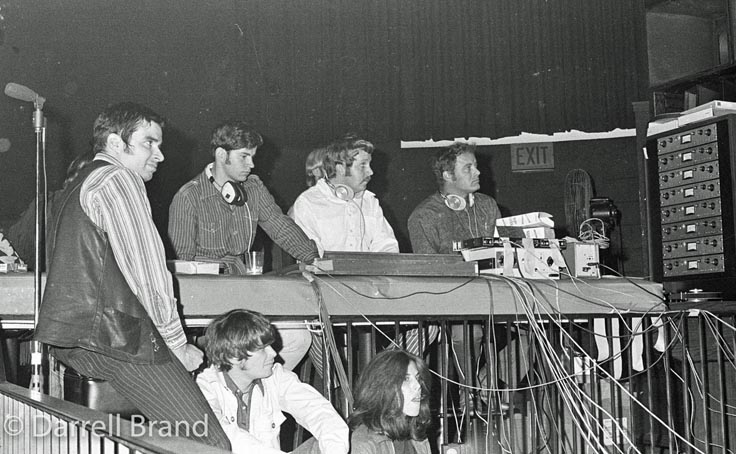

Given the number of disk jockeys in attendance from the big rock stations, it was the place to be. That big honkin’ microphone in the photo below suggests that they might have been doing a remote broadcast as well.

Endorsements were provided on the album by John Pete of KQRS, True Don Bleu of KDWB, and Jimmy Reed of WDGY. All were the top Disc Jockeys of their stations.

THE BANDS

The participating bands varied between those listed on the poster and those that appeared on the resulting album. These are not in the order of the album but start with ones I have pictures for.

Pepper Fog: On poster and album (“Celebration”, written by Gregg Inhofer)

The Litter: On poster and album (“Ungrateful Peg,” written by M. Gallagher and J.S. Jones)

A note from the Litter’s drummer Tom Murray in 2020:

“Ungrateful Pig” was the title of our original song that The Litter recorded for that album. When it was released, the title was changed without The Litter’s permission to “Ungrateful Peg!!” It was wrong for whoever made that decision to change a copyrighted song title to their title that they wanted for the album!! It still irritates me today for what they did!

But the “Gathering at the Depot” album, with all the bands that were on this record, is a great tribute to Minnesota’s music Royalty! Proud I was a part of it!

Crockett: On album only (“Dear Landlord,” written by Bob Dylan)

Thundertree: On album only (“16 Tons,” written by Merle Tillis)

Free and Easy: On album only (“It’s for You” (written by Lennon & McCartney) / “Wake up Sunshine,” written by Robert Camm ). Original members pictured below were, left to right, Tom Behr,Tony Tuccitto, Pat Dee, Dave Vigoren, Tom Mulkern and (unseen in the back), Bobby Gomez on drums.

White Lightning was on the poster but their performance didn’t make it to the album.

- Danny’s Reasons: On poster and album (“With One Eye Closed,” written by Paul Hanson)

- Grizzly: On poster and album (“Get Out of my Life Woman,” written by Paul Butterfield)

- Deadeye: On album only (“Silly Song,” written by Sylvester Stewart)

- Chesterfield Gathering: On album only (“Take Me to the Sunrise,” written by Blues Image)

- System: On album only (“Smiling Eyes,” written by Michael Holm)

- Kiwani: On album only (“Better Days,” written by Wayne Fish)

- Cricket: On poster only. Cricket had been a horn band, but got bumped when they lost their horns, according to Tim Emerson.

- Lemon Pepper: On poster only

- Dave Mark Syndicate: On poster only

SAD NEWS

I’ve had an email from Ralph Ortiz’s daughter, who says that after hauling them around from move to move after her father died, she ended up tossing several boxes of these precious albums away! I paid an arm and a leg for mine! I just noticed that the sleeve on mine had the previous owner’s song reviews on it. One thing he did say was that “This baby got touched up big time in studio.”

BUT ENJOY!

Nevertheless, find one of these if you can, and follow Ralph’s advice:

Progressive Rock, hard rock, rhythm and blues, top 40 rock, or just plain down home funk rock. It’s all part of the “Minneapolis sound” that’s being recognized everywhere in the country. This LP was recorded loud to be played loud. Darken your room, turn your streo on high, sit between your speakers and let the music vibrations turn you on to the sounds of today.

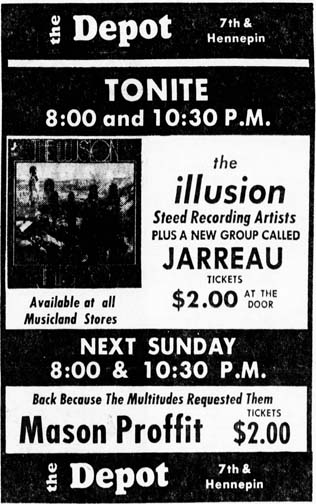

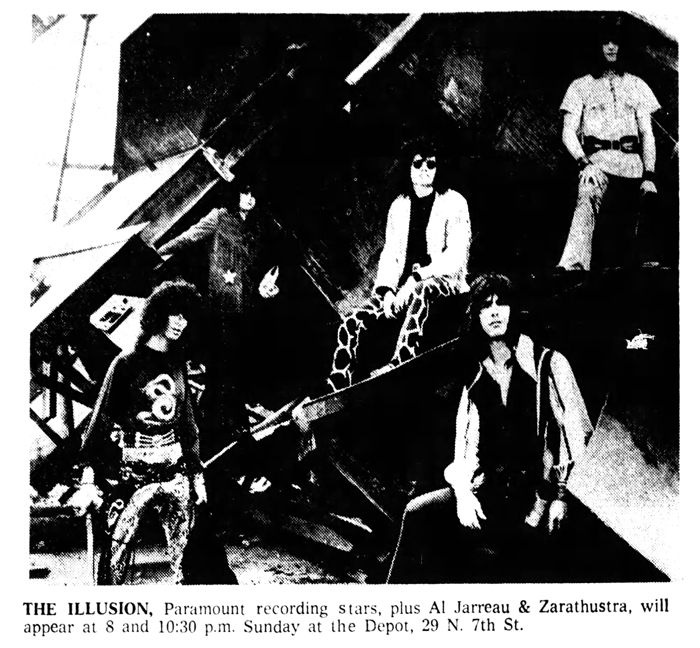

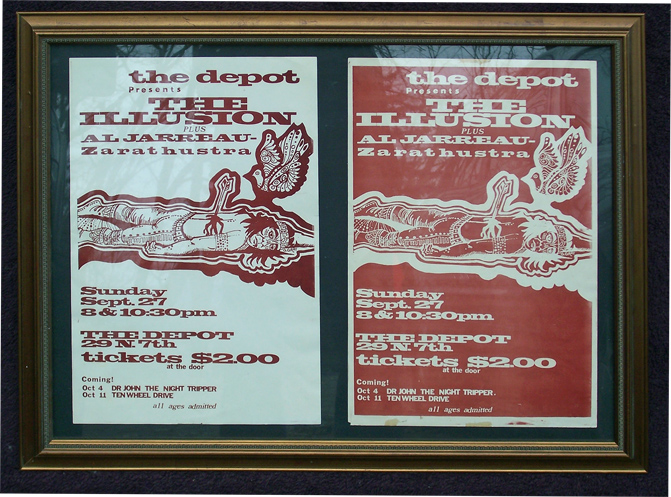

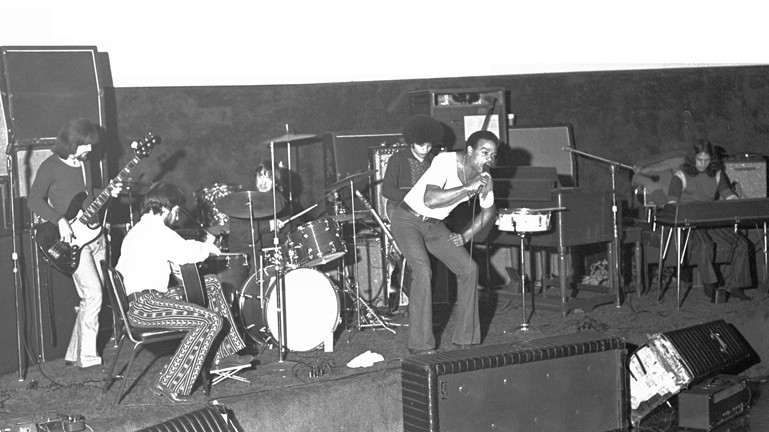

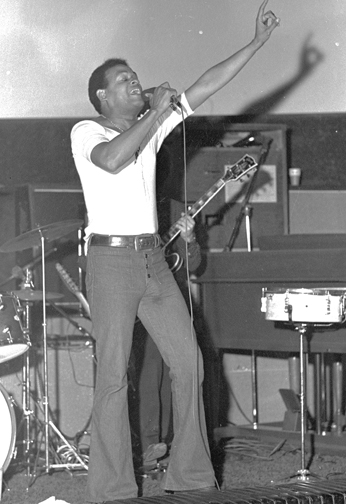

September 27, 1970: The Illusion, opened by Jarreau and Zarathustra.

The Illusion was a psychedelic hard rock band from Long Island. In a news blurb they were described as a five man, up-and-coming rock band with two records out on Paramount. In all, they released three full-length albums in the U.S., produced by Jeff Barry. Their only hit here was “Did You See Her Eyes.”

Read about the band Jarreau here.

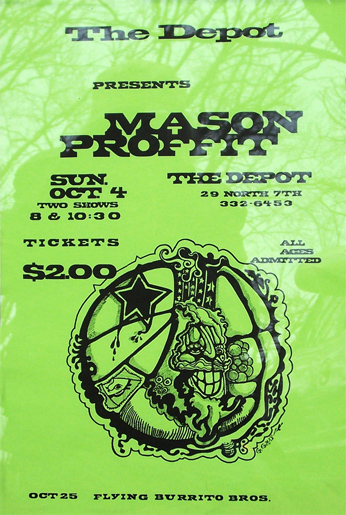

October 4, 1970: Mason Proffit – “Back Because the Multitudes Requested Them.” Opened by Enoch Smoky.

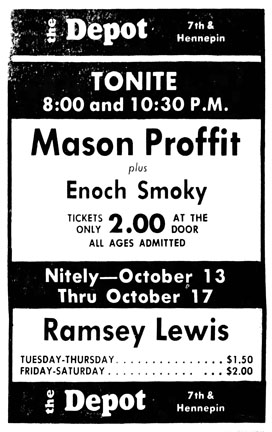

October 13 – 17, 1970: Ramsey Lewis Trio – two shows nightly

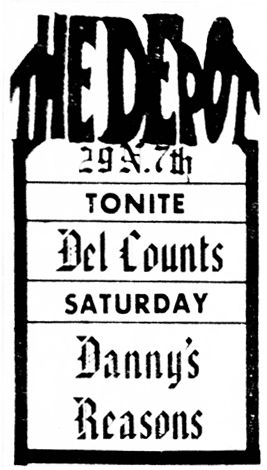

October 23, 19270: Del Counts

October 24, 1970: Danny’s Reasons

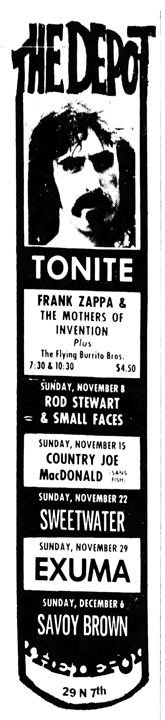

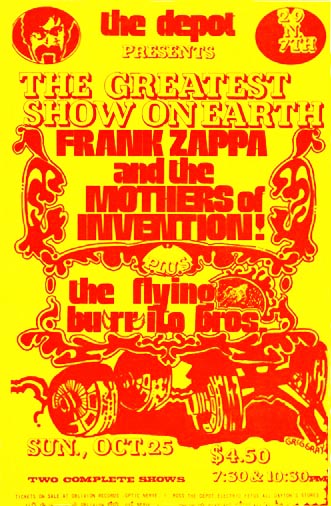

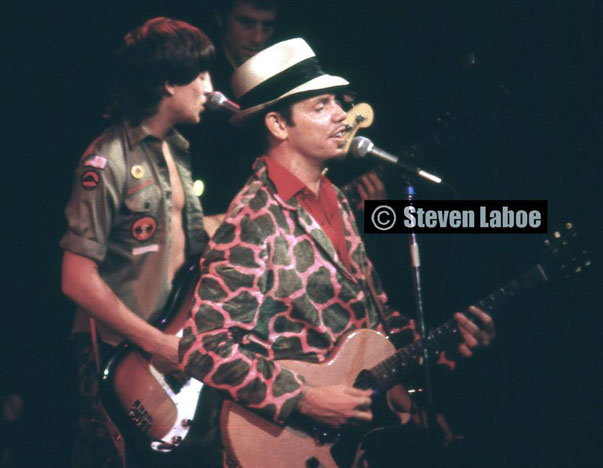

October 25, 1970: Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention and the Flying Burrito Brothers, opened by local/house band Crockett.

What a scene! 1,500 people jammed the Depot for each of two shows.

Hundred Flowers reported that the Flying Burrito Brothers opened, minus Gram Parsons but with pedal steel guitarist Sneaky Pete, Barry Lieden, Rick Richards, and Chris Hillman, the only former Byrd in the group by this time.

The Star’s Peter Altman found the country-rock band to be attractive and well-balanced but “without quite enough personality and fire.” They played bluegrass breakdowns, old hits like “Hand Jive,,” Byrds’ favorites like “One Hundred Years from Today,” neo-cowboy ballads and a song about going to Canada to beat the American draft.” They showed “fluency, a variety of styles, and recalled many eras and personalities. There was an inescapable derivativeness about much of the groups music, however, and a consistent failure to come up with the unexpected.”

Zappa and the Mothers included the Turtles (Flo and Eddie), aka Howard Kaylan (the one with the shirt on) and Mark Volman (the fat one with no shirt on). Hundred Flowers was fixated on Volman, the fat one, apparently often mistaken for Larry Mondello, the fat kid on “Leave it to Beaver.” Volman joined the movement to petition KMSP to put “Beaver” back on TV. Dr. John the Night Tripper was also there in some capacity.

Altman was not at all impressed with Zappa, at least the short 35-minute first show that he saw. “There were scattered shafts of outrageous insult and vulgarity (which were few but funny), but not much else. Musically the group was content to get by with bang, and there was almost none of the weird, oddly appealing sentimentality which in contrast with so much grossness is the key element in the usual Mothers’ formula. [Only] very isolated glimpses were all that could be seen of the Mothers’ antic invention and power to touch…”

Scott Bartell’s review reveals that the Mothers did three long pieces, the first two of which were “Call on Any Vegetable” and “Duke.” Bartell said that Zappa told the audience that they were the most laid-back group he’d ever seen, and downtown Minneapolis was the most laid-back place he’d ever seen. Was that a compliment or a dig? Later Barthell reiterated that Zappa said this was the most polite and receptive audience he’d played for.

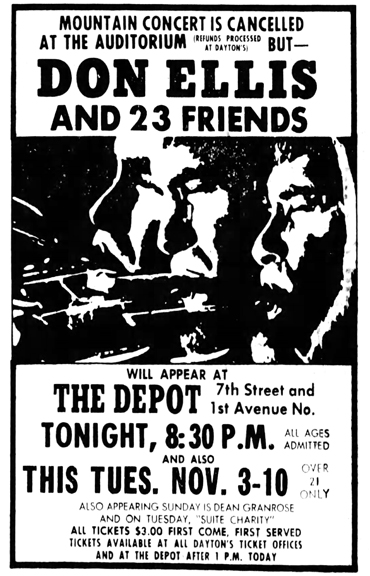

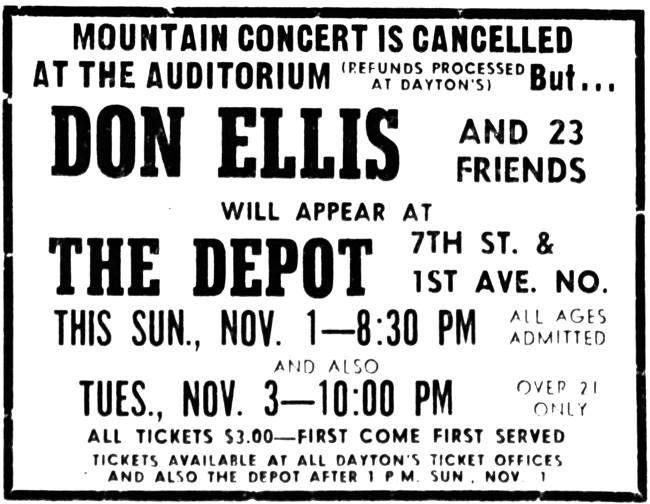

November 1, 1970: Don Ellis and 23 Friends, opened by Dean Granros, Jazz composer and guitarist from Minnesota.

Reviewer Marshall Fine called this “one of the brassiest, most exciting concerts Minneapolis has seen in a long time.” The gig happened because the group Mountain was supposed to perform on October 31, 1970, at the Minneapolis Auditorium, with Ellis as warmup. Leslie West of Mountain fell ill and couldn’t perform, so that concert was cancelled and Ellis was booked into the Depot.

Fine described the group as a “killer band, specializing in polyrythmic swing.” Ellis, “a grinning madman,” played the trumpet and directed the band “with the savagery of a samurai warrior and with the abandon of a man completely married to his work.” Clarinetist Sam Falzone played something called “The Bulgarian Bulge” in 33-16 time. “I mean, nobody plays that fast,” mused Fine. Ellis used something called the Condor, a device that could change the tone and timbre of his trumpet and hook into a tape loop, which allowed Ellis to play a duet with himself.

Will Shapira reviewed the show for the Insider, and called it “one of the most exciting evenings of music we’ve laid on our heads lately.” For the most part the band performed its new album, “Don Ellis at the Fillmore,” and he “tore the roof off the Depot and completely knocked out the audience.” Compared to the live audience on the LP, Shapira opined that the Depot’s crowd was more visceral and “they let it all hang down.”

Ellis and band made an appearance on Bill Carlson’s show “This Must be the Place,” airing on Channel 4 – apparently on December 25, if I’m reading Will Jones’s column of December 27, 1970, correctly. Jones rued that he had missed the live performance at the Depot, and noted that the band had four drummers.

November 3, 1970: Don Ellis and 23 Friends, opened by Suite Charity

One show at 10 pm. See November 1 above.

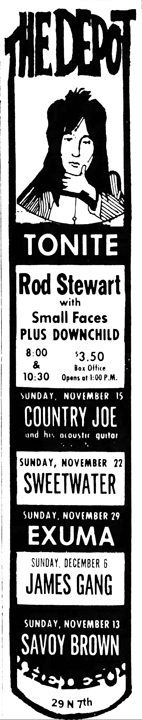

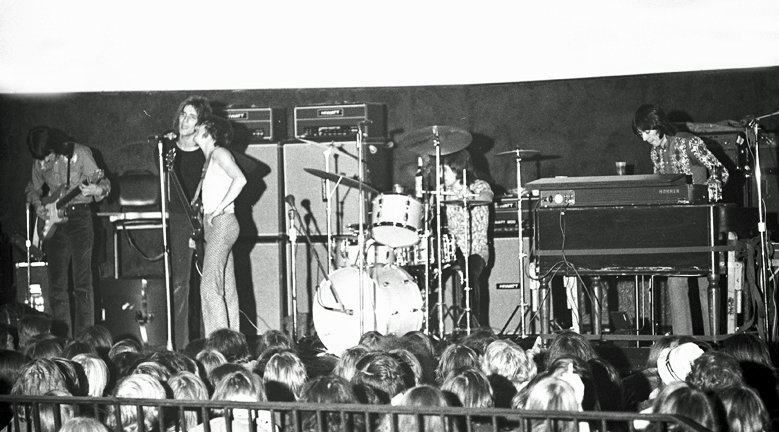

November 8, 1970: Small Faces, featuring Rod Stewart. Opened by local group Downchild.

Pat Marciniak of Hundred Flowers reported that the Small Faces “brought with them a musical sound that’s a big overwhelming combination of musical flowers and colors, along with bright globes of sound. Their concert was thoroughly enjoyable, as was proved by the crowded Depot of fans who cheered with screams and whistles of cries for more.”

The show started late because Ian McLagon’s piano was missing, so the first set only lasted 45 minutes. HF again:

To prove how popular the group really is in the Twin Cities, all anyone wouldn’t had to do was to see the long lines of people standing out in the pouring rain waiting to get into the second show. Only a few had umbrellas, but those who didn’t, didn’t want to move, afraid they might lose their place to see the show.

Scott Bartell’s review in the Strib revealed that it was Early Days for the Faces, and the first show was two-thirds full. Rod Stewart was such a new “face” that Bartell had to describe his voice and approach, which he compared to Joe Cocker, but “minus the worst spastic seizures.” Each song seemed different, with excellent contributions from Ron Wood, Ron Laine, Ian McLagon, and Kenney Jones.

Here’s a story about that concert from Mike Guion:

The Faces were the headliners, and did two shows that night. The second show was to start at 10, but didn’t until after midnight, and despite the late start, the opener did play. By far the most loud show I’ve ever attended, with “Around The Plynth” the highlight, with Woody’s slide shaking the walls. Hard to believe now, but that show did not end until 3 or so. We stood outside in a downpour waiting for the first show to end. Rod had yet to use any hair dye, and the band had to walk from the upstairs dressing room through the crowd to the main floor. Rod’s first solo album was still fresh, and the Faces were touring off their new release called “First Step.” I remember all this so well because I had to be back in downtown at 6 am for my first Army physical. I never got undressed after driving my friends home. Just laid on my bed waiting to take that drive back, wondering if I got drafted where I’d go and what would happen to me. I failed the test. Said I had high blood pressure. I believe the Faces saved my life.

DOWNCHILD

Bartell had a lot to say about Downchild, too, calling them “competent within their tradition (that vast commercial tundra bounded by Blood,Sweat and Tears on the jazzy side and Gary Puckett and the Union Gap on the money side) but they don’t add much to it. I could only listen with half an ear after the first few songs, which gave me time to consider the light show. I considered it pretty dull, though perhaps the groups asked them not to get too flashy. I did like some of the photos of girls, however.”

Jerome Lawrence Beckley of Downchild proudly reports that the band performed all but one original tune. “It was difficult making a living being a concert band doing original material back then.” (The cover tune was Dylan’s “Just Like a Woman.”)

Jerome says that the image above is

part artistic license by my creative friend, David Wood, who created this poster, and Traficante adding our name under the poster design. Our name was fooled with all the time. My favorite was “The Dawn Childs Orchestra.” The name comes from a song by Sonny Boy Williamson, “Mr. Downchild.”

So to be clear, the name of the band was Downchild.

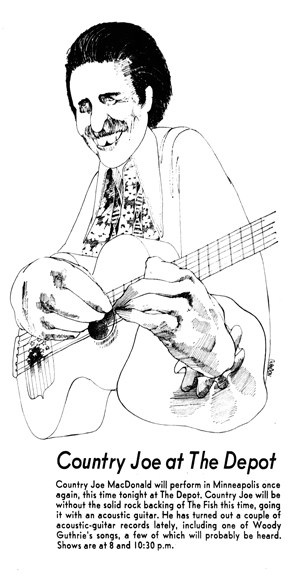

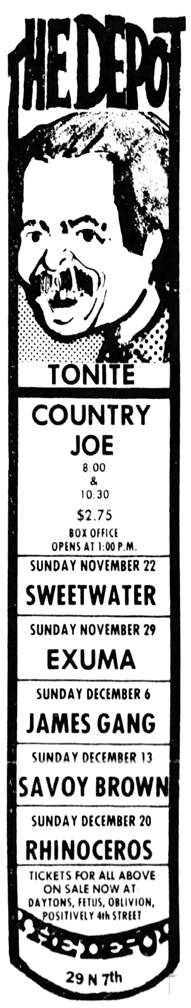

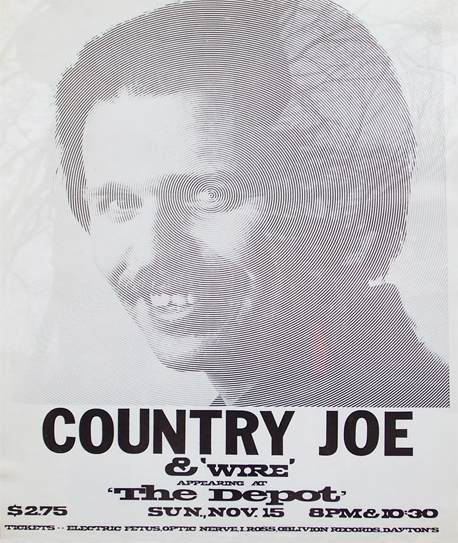

November 15, 1970: Country Joe McDonald (without the Fish). Opened by Wire, a local band featuring Curtiss A (Almstead).

Paul Engel of Hundred Flowers reported that

Country Joe performed admirably, what with the unresponsive audience and the plasticity of the Depot on all sides … It was more like playing in a freakily-painted bus station for the cost of a bus ride from Mpls. to St. Cloud. The performance was lively, expertly delivered, and his material was fresh and poignant.

Dodd Lamberton reviewed the show for the Insider, agreeing that the audience was restrained – but appreciative. The solo acoustic show demonstrated changes for the better, opined Lamberton, citing his “soft, straight-toned voice” and clear annunciation. An interesting observation in the review was that McDonald seemed “pensive and depressed, as if he had just lost a friend” when Lamberton talked to him after the show.

A WORD FROM CURTISS A…

Dodd Lamberton’s review in the Insider included these remarks about Wire, known famously as the first band of local legend Curtiss A:

Wire, the preliminary group, did an amalgamation of oldies and current hard rock songs, from the early Chuck Berry to Savoy Brown. Their vocals were excellent, as they have three men who can both solo and blend well.

Years later, in an interview for KSTP Channel 5 news, Curtiss A had this to say about the show and the venue:

If I’m not mistaken, my first connection to the place was through Danny Stevens. He saw our band and thought we had something. We had played at George’s in the Park (in St. Louis Park) as kind of an audition-type gig, and then we wound up there, including playing with Country Joe McDonald.

I remember the sound system there was really good. I was impressed. Even if it wasn’t what I was expecting from a nightclub, having been a kid and watching TV. It wasn’t Ricky Ricardo and the Copacabana, but it was a great place. And the first couple of times there really did feel like big-time showbiz. We got to essentially debut in the biggest and best place in town, right when it was getting started, and I feel lucky about that.

It’s funny thinking about it now, because back then, I had no idea how relatively an important place it would become in my life. It really gave a focus to all the divergent threads you had in the music scene here, and they’ve always been really supportive of local acts. Some places just have national acts in, and that’s fine if you can sustain yourself that way. But I’ve always felt it’s been more interesting to see all the things we’ve had going on in the Twin Cities too.

At the time of the KSTP interview, Curtiss estimated he’d played the club more than 100 times.

AND THIS:

Don Driggs reported on Facebook:

At that time I was Wire’s manager and I booked that show. Curt was the lead singer. I have vivid memories of going on stage during a song and telling Curt that they were playing too long and if they did not quit, they would not be paid. Curt ran off the stage with me in hot pursuit, chasing him into the back interior parking area. I thought I saw him run into Wire’s bus. I followed but he must have gone out the back door and I lost him. I went back on the stage and searched the crowd – I finally saw him standing in the balcony beside Allen Fingerhut, the owner. Lol. Curt has his own great story about those events. Great Memories..I love that band.

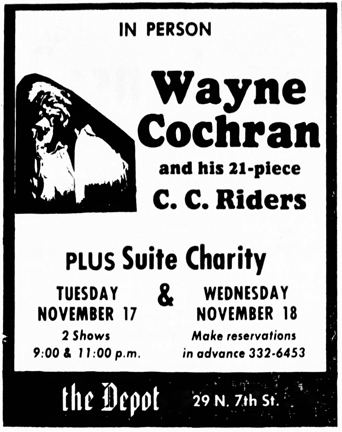

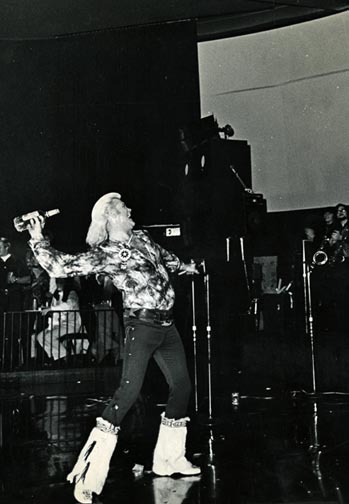

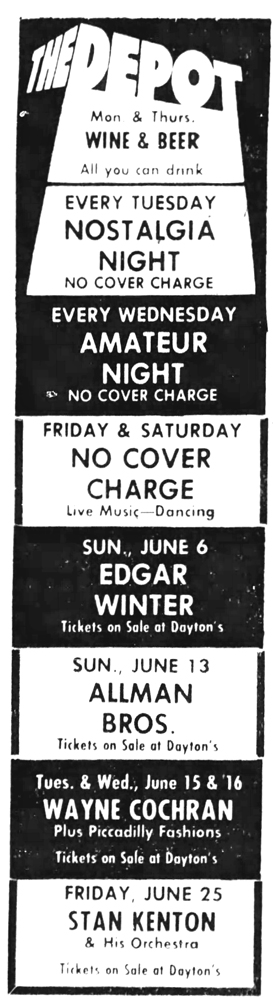

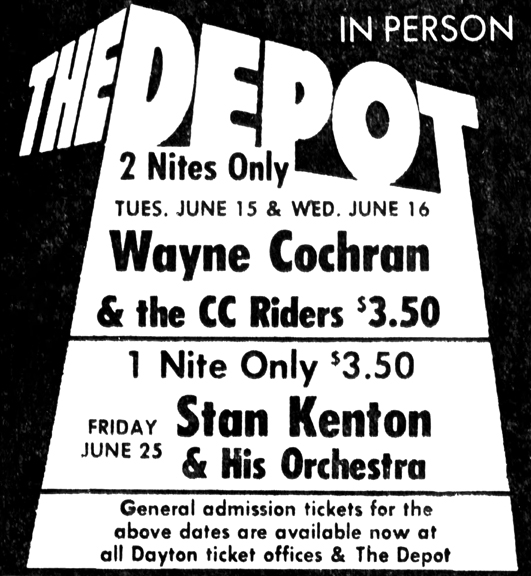

November 17-18, 1970: Wayne Cochran and the CC Riders, opened by Suite Charity