St. Paul Auditorium

St. Paul

This page will attempt to sort out the different venues owned by the City of St. Paul created to host civic events. They include:

- The St. Paul Auditorium

- The St. Paul Auditorium Addition

- The St. Paul Auditorium Theater Section

- Stem Hall

- The St. Paul Civic Center

- The Roy Wilkins Auditorium

Information for this page came from Wikipedia, photos on the Minnesota Historical Society database, the RiverCentre website, and a search of the Minneapolis newspapers. All comments, additions, photos, and corrections are welcome; please feel free to contact me.

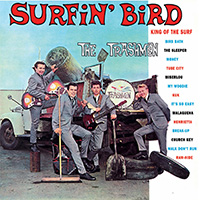

THE ORIGINAL ST. PAUL AUDITORIUM: 1907 to 1982

The original St. Paul Auditorium was built in 1907 and razed in 1982. Like the Minneapolis Auditorium, it had a huge pipe organ, which was sold to the Old South Church in Boston.

ST. PAUL AUDITORIUM (ADDITION): 1932 to 1985

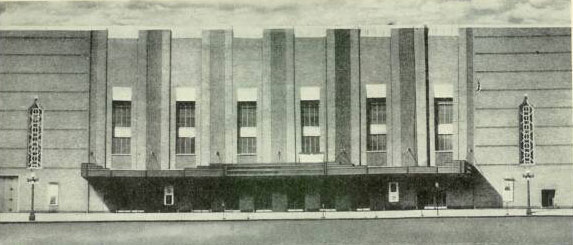

The St. Paul Auditorium addition was built in 1932, at 175 W. Kellogg Blvd., adjacent to the original Auditorium. It was designed by renowned African American municipal architect Clarence W. Wigington.

In 1970, when the building that would become known as the St. Paul Civic Center (see below) was still in its conception stage, ads began calling the St. Paul Auditorium the St. Paul Civic Center. For a while they seemed to be interchangeable – the Jimi Hendrix concert in May 1970 was advertised at both places. On January 4, 1971, Minneapolis Star Outdoor Writer Joe Henessey, when reporting on the first annual Minnesota International Sports, Boat, Camping, and Vacation Show, helpfully says that it will be at “the St. Paul Civic Center (formerly Auditorium).” When that change was made, I didn’t catch. For the record, John Gilbert, the Tribune’s hockey reporter, confirms that the Civic Center did indeed open on January 1, 1973, in his column the previous day, so this naming business is a bit mysterious. What happened when the REAL Civic Center opened? Did the St. Paul Auditorium go back to its original name, or leave us to guess just where some concerts were in St. Paul after about 1970?

In 1985 there was no more St. Paul Auditorium when it was renamed the Roy Wilkins Auditorium (see below).

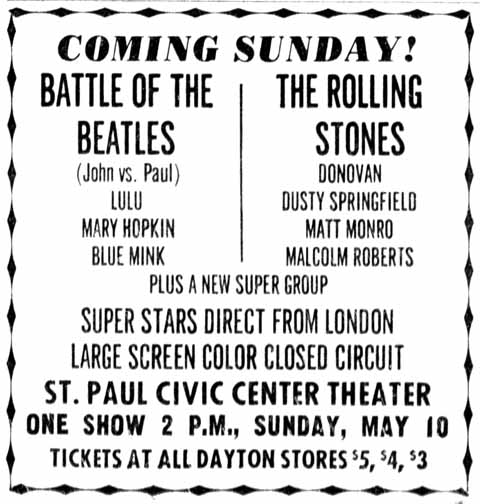

ST. PAUL AUDITORIUM THEATRE: 1932 to about 1980

One new venue included in the addition was the St. Paul Auditorium Theatre/Theater/Theater Section. As its name suggests, this space was mostly dedicated to plays – often traveling musicals. It also hosted ballets, operas, and concerts.

Some non-theatrical entertainment presented at the Theater included:

Stan Kenton with June Christy appeared at the Minneapolis Auditorium Concert Bowl on November 12 and the St. Paul Auditorium Theater on November 13, 1951.

April 29, 1956: Grand Ole Opry, 3:00 and 8:00

May 13, 1956: Elvis played a matinee show here before going over to the Minneapolis Auditorium for an evening performance. See details Here.

November 10, 1957: Jazz for Moderns

October 26, 1958: Louis Armstrong’s performance was booked by promoter Pat Black when he discovered that Armstrong would have a few days between finishing a movie in Hollywood and opening at the Copacabana in New York. He would be accompanied by his usual sidemen: Trummy Young on trombone, Peanuts Hucko on clarinet, Billy Kyle on piano, Danny Barcelona on drums, Mort Herbert on bass, and Velma Middleton. (Will Jones, Minneapolis Tribune, October 21, 1958)

February 22, 1960: Frankie Avalon, backed by the 15-piece Billy Williams Orchestra, made a 2:00 appearance at the Minneapolis Armory and an 8:00 show at the St. Paul Auditorium Theater.

May 19, 1961: Odetta

July 9 to 13, 1963: Harry Belafonte

March 7, 1964: Allen Sherman

Ray Charles performed at the St. Paul Auditorium Theater on October 9, and the Minneapolis Auditorium on October 10, 1964.

On November 19, 1966, the Dave Brubeck Trio appeared at the Theater.

The musical “Hair” was booked at the Theater from February 23 to March 7, 1971, and so many ticket requests had to be returned that a repeat performance that May. It was the first show ever to be brought back to the Twin Cities for a second run in the same season.

They also started showing special events on closed circuit TV, such as the 1970 Indianapolis 500. And this:

Poco and a “special performance” by Shawn Phillips came to the St. Paul Auditorium Theater on May 21, 1971.

Edgar Winter was at the St. Paul Auditorium Theater on February 16, 1973.

The last mention I found in the Minneapolis papers was in November 1978.

STEM HALL: 1932 to about 1980

Stem Hall was another new venue added in 1932, smallest of the three spaces in the building, holding a little over 1,000 people. This picture of Manuel and Dorothy Aguirre dancing at Stem Hall in 1964 shows the inside.

Stem Hall was heavily used for boxing and wrestling matches, lectures, antique shows, poultry and other animal shows, majorette contests, and some concerts.

Little Old Lady Blows Up Stem Hall

During World War II, Stem Hall (along with the YMCA and YWCA) hosted “Swing Shift Dances,” presumably for people to while away the time between their job shifts. Well, a little old lady named Miss Elizabeth Flynn was irked that these folks should be home taking care of their children, so she wrote a letter threatening to blow up the sites of these dances, including Stem Hall. She confessed that she didn’t know how to blow up buildings, but just wanted to scare people into doing something about the problem. “I thought maybe they’d think I was a big gang of outlaws and do something.” (Minneapolis Tribune, June 19, 1943)

A dance honoring four black baseball players, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Roy Doby, and Satchell Paige, was held at Stem Hall on October 30, 1948, sponsored by the Harlem Jive Club. (Minneapolis Star, October 29, 1948)

Black Muslims at Stem Hall

On May 17, 1964, “members of two Twin Cities black Muslim sects” met at Stem Hall after a protracted discussion by the St. Paul City Council, the owners of the St. Paul Auditorium. Because the group was in favor of black separatism, and the City was worried about racism – or reverse racism, since whites would not be welcome. The meeting was attended by 100 of the “American so-called Negro,” as referred to by main speaker Louis Shabazz (Louis X), Muslim leader from Boston. Everyone was thoroughly searched by “members of the sect,” including the approximately 20 white journalists on hand.

The message of the meeting was that the American government would eventually give Negroes land of their own, because “the government does what is expedient.” If not, God will intervene, and “it will be very, very, very serious and very painful.” Minneapolis Tribune reporter Irv Letofsky wrote a very detailed article about the meeting and the group’s ideology on May 18, 1964.

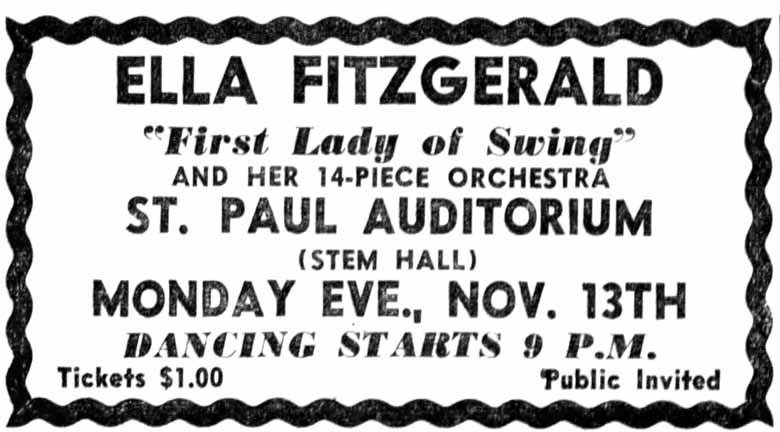

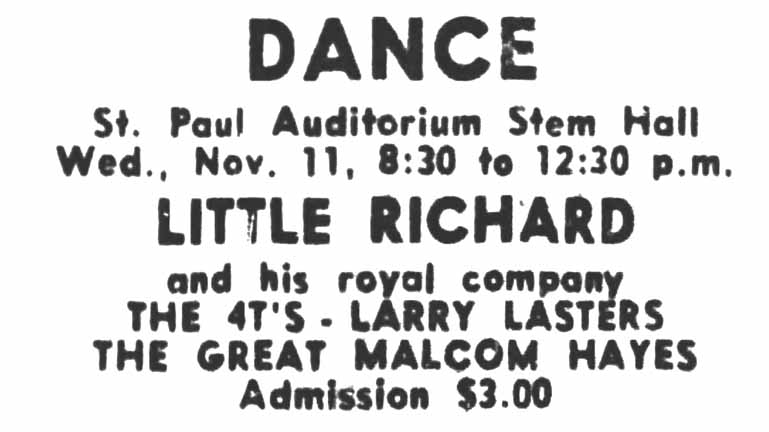

Little Richard and his Royal Comany appeared at Stem Hall on November 11, 1964. Also appearing were The 4 Ts, Larry Lasters, and the Great Malcolm Hayes.

TRAGEDY AT STEM HALL

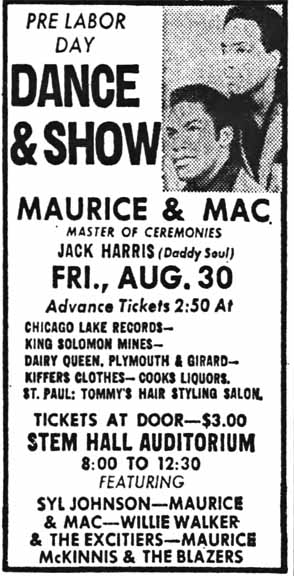

On August 30, 1968, a concert and dance was held at Stem Hall, emceed by Jack Harris, a/k/a disc jockey Daddy Soul on radio station KUXL. Performers included:

- Syl Johnson

- Maurice & Mac

- Willie Walker and the Exciters

- Maurice McKinnis and the Blazers

These groups were well known in clubs like King Solomon’s Mines where Soul music was a staple.

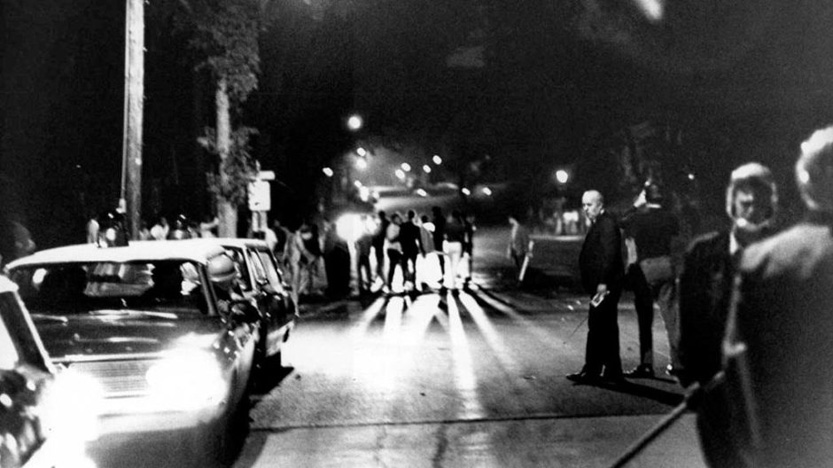

What should have been a fun night turned into two nights of fear, anger, and violence – not only because of a situation handled poorly but because of underlying conditions that faced black communities all across the country.

The facts, as reported in the newspapers and in investigative reports approximate these. About 350 young people, mostly black (I’ll use that word instead of the word Negro used at that time) were in attendance. One young man was in a rest room with some others who were drinking, and he flashed a gun. It was never clear whether he used it or even who he was. Two off-duty policemen who were hired for the event came on the scene and took the gun away from him and tried to arrest him. They were attacked by about 20 men who tried to retrieve the gun. The policemen called for backup and the melee started. A gunshot was heard and a policeman was hit in the arm or hand. The shooter was never identified.

At that point, having lost the opportunity to peacefully arrest the young man, the police decided to use nightsticks to bar the door to the hall, keeping the people in. They broke through one of the doors, and then the police decided to keep them back by lobbing teargas into the crowd. Thus incited, the crowd began yelling invectives at the police and throwing furniture at them. Once outside the missles became rocks. Mob violence ensued and the car of KSTP-TV newsman Dave Margeson was smashed by rocks and a piece of wood; he was treated and released from the hospital. The crowd moved west down 4th Street, smashing store windows, until they got to the Selby-Dale neighborhood, where many of the City’s 10,000 black people lived in what could only be described as a ghetto. The disturbance was considered contained by 2:30 am.

Seven people were arrested the first night. Two of them, a married couple, were from Minneapolis, and they had a loaded submachine gun in the trunk of their car and a .45 pistol under the seat. Whether this was related to the disturbance was not quite clear.

The next night, violence continued on its own momentum. At about 9:30 pm, someone with a shotgun wounded three police officers who, with about 20 others, were trying to break up a crowd of about 200 who had gathered at the site of a firebombing. A police command post was set up at the St. Paul Cathedral, and two-man tear gas units were sent around, with police at every intersection. Cars were prevented from coming into the area from Interstate 94 at the Dale Street exit. Four businesses were fire-bombed and fire trucks were met with sniper fire but no one was injured. Ten people were arrested, most for carrying firearms. Two white youths from upstate Minnesota were arrested in a house when spotted brandishing a shotgun on a balcony.

In the wake of the incidents, a committee was formed by the St. Paul Urban Coalition to investigate them. Sixteen pastors gathered to support this action and expressed their concern that the investigation be impartial and representative. The St. Paul Urban League and the St. Paul Human Rights Department also launched their own investigations. Meanwhile, the Mayor and others defended the actions of the police and laid the blame squarely on the “mob.”

The report by the St. Paul Human Rights Department, released in February 1969, placed the blame for the disturbances mainly on how the police handled it. While their job was to arrest one man with a gun, they instead barricaded the door of the hall with their night sticks and used tear gas to subdue the crowd. An underlying cause was said to be the overall condition of the Selby-Dale area.

The report of the St. Paul Urban Coalition, headed by Arthur S. Fleming, President of Macalester College, was released in March 1969 and echoed the first but was much more detailed and damning. The decision of the police to bar the door and throw teargas into the hall was roundly criticized. A policeman knocked down pregnant woman, pulled her hair, and threw her into a wall. A 15-year-old polio victim was smashed, face-first, into the pavement and sent home bleeding. The biggest troublemakers appeared to be a group of about 30 from Minneapolis, dressed in boots, Levi jackets, blue jeans, and cowboy or Australian “digger” hats.

And although much of the 96-page report centered on the disturbances themselves, the committee had plenty to say about “discrimination patterns in housing, education, recreation, employment, welfare, and police-community relations, and includes recommendations for improvement in those areas.”

Sources:

- Minneapolis Tribune, August 31 to September 2, 1968

- Minneapolis Star, August 31, 1968

- Minneapolis Tribune, February 2, 1969

- Minneapolis Star, February 6, 1969

- Minneapolis Tribune, February 9, 1969

- Minneapolis Tribune, February 12, 1969

- Minneapolis Tribune, March 19, 1969

- Minneapolis Star, May 7, 1969

In December 1978 Stem Hall became the new home of the Twin City Model Railroad Club

The last mention I found of Stem Hall in the Minneapolis papers was in May 1980.

See the text of a 2018 article about the Stem Hall riots at the end of this page.

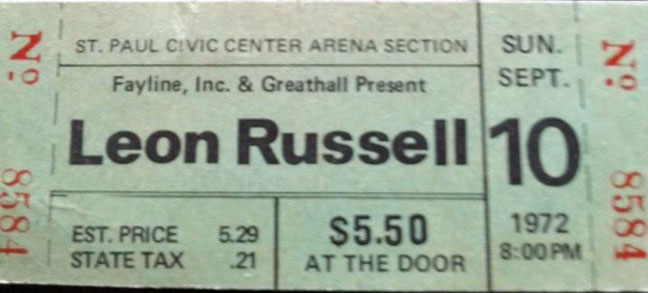

ST. PAUL CIVIC CENTER: 1973 TO 1998

This part is very confusing, because concerts began to use the term “St. Paul Civic Center” or “St. Paul Civic Center Arena” long before the venue supposedly opened on January 1, 1973. A search of my own Events page shows Jimi Hendrix appearing there in 1970. Further research shows that the show was actually at the St. Paul Auditorium, but the ad, placed by Pepsi, the sponsor, did indeed call it the St. Paul Civic Center. This was at a time when the financing for the Civic Center was still being negotiated.

The information below courtesy Vintage Minnesota Hockey:

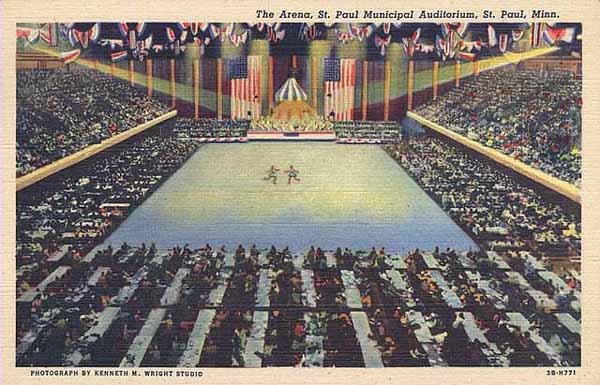

The St. Paul Civic Center was an indoor arena that opened on January 1, 1973. It was the home of both incarnations of the Minnesota Fighting Saints of the WHA – the first from 1973-1976 and the second from 1976-1977. The arena seated 16,000.

The Civic Center is best remembered for its unique hockey boards that were made of clear acrylic glass all the way down to the ice, installed at the urging of Civic Center Director John Friedmann. In 1973 Friedmann said, “I saw them on TV during the Winter Olympics in Sapporo, Japan, in 1972, and felt those would be great for better fan enjoyment while watching hockey.” The iconic clear dashers were made by Safeway Steel of Milwaukee. “They cost us $85,000 in 1973, but would probably cost between $200,000 to $225,000 today. The arenas in Sapporo and St. Paul are the only ones in the world thought to have the clear boards,” said John Friedmann.

The seating configuration of the “Madison Square Garden of the North,” as the Civic Center became known as, was round, meaning that the closest seats at center ice were not right up against the glass. The clear dasher-boards made for better sight-lines for those spectators.

Also of note, the principal architect for the Civic Center was Len Lilyholm, who found himself right at home within the Arena as a player with the Minnesota Fighting Saints hockey club.

The last professional hockey team to skate in the Civic Center was the IHL Minnesota Moose hockey club from 1994-1996. The clear boards were replaced with normal wood boards when the Moose played there, as the professional team needed to be able to sell advertising on them. This ruined the sight-lines for what should have been the best seats, and proved that in order to get an expansion NHL team, a new arena was needed. The Civic Center was torn down in 1998 to make way for the Xcel Energy Center, which was built in exactly the same location as the old arena.

The Xcel opened in 2000 with the Minnesota Wild, and subsequently hosted the return of the State High School Hockey Tournament to play in St. Paul.

ROY WILKINS AUDITORIUM: 1985 to Present

In 1985 the St. Paul Auditorium Addition (then just the St. Paul Auditorium since the original building was demolished in 1982) was renamed for Roy Wilkins. It is part of the St. Paul RiverCentre complex that includes the Xcel Energy Center.

The building was renovated in 1986. The building is now composed of:

- The 44,800 square ft. Roy Wilkins Auditorium, which offers 5,844 seats for concerts, speaking, or sporting events.

- The 30,000 Exhibit Hall, is directly accessible from the adjacent Saint Paul RiverCentre. It can be used for a variety of purposes including dining, exhibiting or changing rooms.

- The Roy Wilkins Dance Studios, which provide professional space for rehearsal, social, and competitive dance. The space features four 3,200 square foot studios with 40′ x 60′ dance areas in the former upper ballrooms of the Roy Wilkins Auditorium.

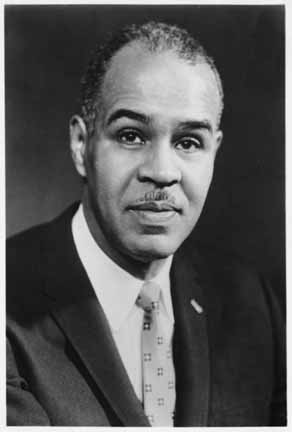

ROY WILKINS

From the Roy Wilkins Auditorium Website:

Roy Wilkins was an activist who was determined to earn rights for blacks using all legal means of protest while preaching peaceful actions. Though he was born in St. Louis, Missouri, it is Saint Paul, Minnesota, that will always have the honor of claiming Wilkins as its own. In turn, one of the most prominent figures in America’s civil rights movement was proud to call Minnesota’s state capital his home.

From 1932 to 1977, Wilkins served on the NAACP as assistant executive secretary, executive secretary and eventually, the executive director, a post he held for 22 years before retiring. During his tenure at the NAACP, he also succeeded W.E.B. DuBois as editor of Crisis Magazine, the organization’s official publication. He served as an advisor to the War Department during World War II, and acted as a consultant to the American delegation at the United Nations conference in San Francisco. He also led the fight to end school segregation.

In addition to displaying his heroism in such movements as the “March on Washington” in 1963, the “Selma to Montgomery March” in 1965, and the “March Against Fear” in 1966, Mr. Wilkins established himself as an articulate spokesman and leader. He testified before numerous congressional hearings, wrote for several publications, and was an advisor to United States presidents including John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter. Wilkins was also instrumental in leading campaigns for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Wilkins’ colleague Joe Rauh described how the leader was as important to the American Civil Rights Movement as Martin Luther King, Jr. “I guess you can say Martin was the front man who changed public opinion,” said Rauh. “But Roy was the one able to use that shift in public opinion to bring about legislation and legal rulings that benefited blacks, as well as any number of other people.”

Throughout his prestigious career, Wilkins received numerous national accolades for his determined, yet peaceful efforts. In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson bestowed Wilkins with the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Perhaps his most notable recognition was the request of President Ronald Reagan to have all Government flags flown at half-staff on September 9, 1981, the date of Wilkins’ passing.

50 years ago, St. Paul police tear gassed a barricaded dance hall. So began the Stem Hall race riots

By Nick Woltman | [email protected] | Pioneer Press

PUBLISHED: August 31, 2018 at 8:42 am | UPDATED: September 2, 2018 at 10:34 am

Six months pregnant in late August 1968, Teretha Glass-Kelly was feeling cooped up in her St. Paul home. So, when she heard about a dance downtown on Labor Day weekend, she wasn’t about to miss it.

“I decided I was going to go out and have a good time,” said Glass-Kelly, who will turn 70 this October. “I put a lot of work into looking cute, and not like some pregnant person.”

Local R&B groups the Exciters and the Blazers were playing that Friday at Stem Hall, which sat next to Roy Wilkins Auditorium until it was demolished to make way for the Ordway Center for the Performing Arts.

While Glass-Kelly was dancing with her sister and some friends that night, a pair of white St. Paul police officers, who were providing security for the nearly all-black event, tried to arrest a young man who flashed a pistol in a basement bathroom.

When he and his friends resisted, the confrontation escalated and the officers called for backup. During the ensuing scuffle, an officer was shot in the shoulder.

Inside the dance hall, this commotion went largely unnoticed by the revelers.

“We were in there having fun,” Glass-Kelly said. “We didn’t even know anything was wrong until the tear gas came in. You heard this thing come sliding across the floor and people screamed.”

The crying and coughing crowd of roughly 500 rushed for the exits, but they found the doors barred shut by police nightsticks.

When the young people finally got outside into the fresh air, they were confronted by a wall of officers and squad cars.

“To me, it looked like a set-up,” Glass-Kelly said. “You got out there and they’re lined up. Was this pre-planned?”

The situation soon erupted into what became known as the Stem Hall Riots. That Labor Day weekend saw 26 arrests, dozens of injuries and three more police officers wounded by gunfire. A handful of white-owned Summit-University businesses were firebombed.

The unrest shook St. Paul, which had largely avoided the widespread racial violence that elsewhere marked the late 1960s. The St. Paul Urban Coalition and the city’s Human Rights Department both commissioned studies to determine the cause of the riots.

Their investigators interviewed hundreds of witnesses and community members in the months that followed, including Glass-Kelly. They released their reports in February 1969.

“Civil disorders are the products of hundreds and hundreds of little humiliating events,” wrote Human Rights Department director Louis H. Ervin in his agency’s report.

“The tensions and frustrations of the St. Paul Negro Community have been created by so many factors and been bottled up so long that disorder seemed inevitable. Something had to give.”

‘A POWDER KEG’

The Urban Coalition and Human Rights Department probes both found that the inequality faced by black St. Paulites in education, employment and housing had for years been ignored by the city.

The 1960 census found 26 percent of black households in St. Paul living below the poverty line, compared with just 12 percent of the white households — a gap that is even wider today, according to the latest American Community Survey.

In 1968, 85 percent of St. Paul’s black residents lived in its Summit-University neighborhood, which was plagued by substandard housing and absentee landlords.

And although the city’s black population had grown by at least 35 percent since 1950, the Summit-University area had lost nearly 1,100 housing units to demolition in roughly the same period, which caused overcrowding, according to the Urban Coalition report.

The schools serving students in this neighborhood were similarly inadequate, despite two decades’ worth of St. Paul School Board studies recommending improvements, the Urban Coalition report said.

Both reports also highlighted the black community’s mistrust of the city’s overwhelmingly white police force; it employed only four black officers at the time.

The Human Rights Department had held three listening sessions on police-community relations earlier that year after receiving a series of complaints about officers’ treatment of black citizens.

After a race riot in Minneapolis the previous summer — purportedly sparked by police mistreatment of a black woman at the Aquatennial parade, according to the Minnesota Historical Society — rumors that similar violence would soon visit St. Paul circulated among its white residents, news reports said.

“It was a powder keg,” said Fred Kaphingst, a retired St. Paul police officer who was on duty the night of the dance at Stem Hall.

TWO NIGHTS OF RIOTING

Kaphingst was working the Minnesota State Fair that Friday, when his sergeant came rushing over to tell him that all sworn officers had been ordered to a riot downtown. Kaphingst picked up a helmet, riot stick and gas mask from headquarters and hurried over to Stem Hall.

When he arrived, most of the crowd had already obeyed police orders to disperse. Glass-Kelly and about 150 others remained, either because they had no way to get home or because they were angry about being tear gassed for no apparent reason.

“They’re saying, ‘Move out, move out.’ But where in the hell are you supposed to go?” Glass-Kelly said. “There were no cellphones. How do you get in touch with the person who’s supposed to pick you up?”

Some of the young people hurled bricks, bottles and insults at officers, according to the Urban League and Human Rights Department reports.

“They’re yelling and they’re throwing rocks,” Kaphingst said. “I got hit in the legs a few times — nothing serious.”

Other officers weren’t so lucky. At least one was knocked to the ground by a rock that hit him in the forehead.

When police finally pressed forward to break up the crowd by force, it split into two groups — one running east and the other running west. The officers pursued both.

Glass-Kelly was in the eastbound group, but she had to stop behind the public library because of a pain in her stomach. A police officer knocked Glass-Kelly to the ground with his nightstick, kicked her in the side and pulled her hair, she later told investigators.

“I was pregnant, but I didn’t tip the scale past 138 or 139,” Glass-Kelly said. “There’s no need to hit me or knock me down.”

Another officer helped Glass-Kelly into his squad car and drove her to the hospital, where doctors found that she was bruised but her baby was healthy.

In the westbound group, a 15-year-old boy, who told investigators he had recently undergone surgery on one of his legs, fell behind his friends on Kellogg Boulevard and was hit with a nightstick by an officer. A wound on his head required at least five stitches.

Meanwhile, the majority of the crowd worked its way up Cathedral Hill to the Summit-University area, assaulting bystanders and breaking the windows of businesses, homes and automobiles along the way, the reports said.

Kaphingst and his fellow officers cordoned off much of Selby Avenue and spent the next several hours racing from call to call.

Ed Steenberg, another retired St. Paul police officer, was at home sick with a 102-degree fever that night, but he was also summoned to the riot because he walked a foot patrol on Selby. His superiors hoped he could leverage his connections in the community to calm the rioters.

“I knew everybody,” Steenberg said. “When you’re walking a beat, you get to know the people under a whole different set of circumstances.”

Steenberg helped gather some clergy and community leaders who asked the young people to go home, but to no avail. Things didn’t quiet down until about 4 a.m.

The next night, Kaphingst was back at his post at the State Fair when his sergeant again raced over to relieve him, saying that buildings were burning in Summit-University.

Molotov cocktails had ignited three neighborhood businesses shortly after 9 p.m., and the firefighters sent to extinguish the blazes were being shot at. Officers searching for their assailants were hit by shotgun pellets.

Two pairs of white men with shotguns were arrested in the area that night but neither was charged with the shootings, according to newspaper reports.

Kaphingst and Steenberg again worked through the night, but Saturday was comparatively quiet.

“It petered out early in the evening,” Steenberg said. “Their numbers were so much smaller that it wasn’t so much an issue from then on.”

AFTERMATH

In the weeks after the riots, the Human Rights Department and the Urban Coalition undertook their independent investigations of the violence. While Ervin led his department’s efforts, the Urban Coalition recruited then-Macalester College President Arthur Flemming, who would go on to serve as chairman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights under four presidential administrations.

Both groups faulted the police for tossing tear gas into a locked dance hall full of innocent people.

“The gas affected the crowd indiscriminately,” the Urban Coalition report said. “It is clear that from the time the gas was thrown into the hall, a wider disturbance was beyond prevention.”

But they also credited the police for their restraint during the subsequent riots.

The Human Rights Department said it was “critical of some ineptitude, even misconduct, on the part of members of the police and of the level of their training in general. While this can be said, it ought not to, and will not, detract from the exemplary conduct of many assembled officers, who maintained discipline under pressure and who endured gunfire and danger without similar response.”

The reports praised members of the city’s black community, too, for working to contain the violence that weekend.

“It could’ve been worse,” Steenberg said. “I would say that both sides tried to keep it down.”

Glass-Kelly, who delivered a healthy baby boy three months after the riots, has tried to put the events of that weekend behind her, not even telling her kids about it in detail.

“It’s not anything that I talked about,” she said. “You don’t want to say, ‘Yeah, these cops did that to me,’ and ingrain this kind of thing in them about police officers.”

Growing up in the Rondo neighborhood in the 1950s, she remembers only positive encounters with police — especially a beat cop who was beloved by neighborhood kids.

He had a gun, he had a uniform, but nobody feared him,” she remembered.

But her experience at Stem Hall forever changed the way she viewed law enforcement.

“That incident was my first real eye-opening to what police could actually do to people,” Glass-Kelly said. “I do not believe — and there’s no way anybody can ever convince me — that every cop is a bad cop. But I know that there are some bad cops.”