Harlem Breakfast Club

Highland Ave.

Minneapolis

The Harlem Breakfast Club was a “Black and Tan” jazz club or “resort” in the terminology of the newspapers of the day. It had two locations, both on Highland Ave. on the North Side of Minneapolis.

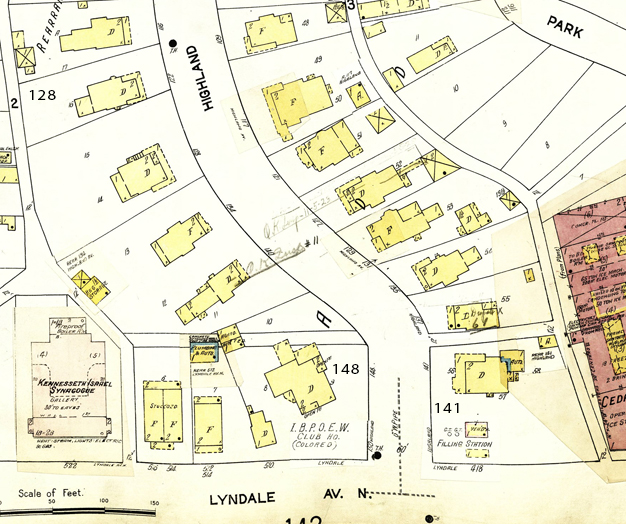

Thanks to the map below, we know that 141 Highland was just across the street from the Elk’s Club, which was at 148 Highland. The Breakfast Club’s other location was at 128 Highland, on the other side of the street and down a few houses.

Map courtesy Hennepin County Library

Although there is a photo of the Elk’s Club, there are, unfortunately, no known photos of 141 or 128 Highland. It’s a bet, however, that they were old homes in the Oak Lake Park subdivision. Never heard of Highland Ave? Here’s an explanation, paraphrased from Kirsten Delegard’s report:

Oak Lake Park was an upscale Victorian neighborhood that had its glory years when Minneapolis was in its infancy. Today there is no trace of its curving streets and gingerbread-ornamented wooden homes. The once-wealthy subdivision was bulldozed to make way for a new farmer’s market on the edge of downtown.

Our community’s history of urban redevelopment actualy started, in earnest, with Oak Lake Park. When it was first developed in the 1870s, this neighborhood was home to some of the city’s most affluent residents. These were not the grand mansions of Park Avenue, but rather than homes of successful professionals, like Dr. Augustus Harrison Salisbury, whose grandson Harrison Salisbury would grow up to become a world-famous foreign correspondent.

Residents of the leafy subdivision established the city’s first neighborhood association, which built a small bandstand next to the tiny Oak Lake. And they created the city’s second park, after Murphy Square. But the idyllic neighborhood was quickly overwhelmed by the growing city. Bordered by a growing network of railroads and an increasingly filthy Bassett Creek, Oak Lake Park rapidly fell from grace. People with means were pulled east by Loring Park. By the first decade of the twentieth century, the neighborhood on the edge of downtown had become, in the words of Harrison Salisbury, “the most alien corner of that most Middle Western city of Minneapolis.”

By the 1930s, the city had condemned Oak Lake Park as a slum. This neighborhood was the first target of a three-decade long urban renewal campaign in Minneapolis that would obliterate much of the city’s historic streetscape. Think about Oak Lake next time you visit the downtown Farmer’s Market. It lies buried under the concrete expanse, invisible to modern view.

141 HIGHLAND AVE.

141 Highland had a history of illegal alcohol, apparently – in 1923, a still that was located in the attic exploded with such velocity that it nearly wrecked the house, causing $1,200 in damage.

THE BREAKFAST CLUB

1932

The first restaurant license was applied for in June 1932. This may have been the Musicians’ Rest. Or not.

1933

In May 1933, Philip Ware received a liquor license very soon after the end of Prohibition. It’s fair to assume that this was the beginning of the Harlem Breakfast Club.

Saturday Press, March 1934

1934

An interesting item from the September 14, 1934, issue of the Minneapolis Spokesman:

The wee hours of the morning at the Harlem Breakfast Club now bring forth a number of University of Minnesota campus big-shots. I noticed two girls who are members of Kappa Kappa Gamma, the snootiest of the campus sororities, a young man well-known in collegiate social circles, and another biggy-wig, – all of them apparently enjoying themselves immensely the other yawning about four. If you know Who’s Who around Minneapolis, you will be surprised at the number of them who frequent sepia night spots …

1936

IT’S A RAID! NO. 1

Ware was arrested with three others in a raid on February 25, 1936, when officials found a gallon of moonshine whiskey. But it was found that since repeal of Prohibition, State law made it impossible for the county attorney to start abatement proceedings against the club upon liquor convictions along, so all charges were dismissed on March 13, 1936, based on insufficient evidence. (Minneapolis Tribune, March 15, 1936)

The last mention of the Harlem Breakfast Club at 141 Highland was also on March 15, 1936 – the Mayor said there was no point in pulling the license since the ramshackle house was slated for demolition to make way for the Municipal Market.

128 HIGHLAND AVE

By July 1936, the Harlem Breakfast Club was up and running again, this time in a building that was across the street and about three doors down. It was built before 1884, the home of lawyer Stanley R. Kitchell. But by 1911 it was a duplex, and in 1934 it was a 13-room rooming house.

Despite the raid earlier in the year, Philip Ware was again running the Harlem Breakfast Club, now here at 128 Highland.

MAPLE LEAF CLUB

Philip Ware was back, managing this new club at 128 Highland. The Spokesman began either running very small ads or including it in a list of businesses to use, on August 13, 1937. What’s odd is that while the Spokesman refers to it as the Maple Leaf Club/Musicians’ Rest consistently through November 17, 1939, the Star and Tribune just as consistently called it the Harlem Breakfast Club during the same time.

IT’S A RAID! NO. 2

1940

The Maple Leaf Club/Harlem Breakfast Club was back in trouble again. On August 11, 1940, Detective Sig Couch, described as the Police Department’s one-man morals squad, conducted a raid on the Harlem Breakfast Club. The Minneapolis Tribune‘s fanciful report of this event will bear repeating in this account.

Detective Couch has figured it out: If you can keep the customers away from the the joints, there won’t be any joints.

The raid began at 3:45 am. Undercover men, each with a girlfriend, were seated in each of the four rooms used for service on the first floor. The officers used small hot water bottles to capture samples of liquor served after hours.

When the raid began, hilarity was at an early-morning height. Glasses were on the table. The orchestra were playing. Laughter ran from group to group.

“One-man” Couch ran true to type by going in first, alone. His good-natured countenance quenched nobody’s fun, with one exception. Detective Couch said Everything went on as before, except that when Philip Ware, Negro, recognized him, Ware’s face fell as if it had been dropped from a great height.

Ware started for a back room. When Couch caught up with him, Couch said, Ware had a finger on the button of a buzzer. Couch and some of his helpers traced the buzzer wires to an upstairs room. There seven Negro men were sitting in pointedly innocent attitudes at a round table. Two other men were standing, fixedly watching them do it. Nobody was saying a word.

… Couch was impressed by the numbers of persons who had just dropped in for a coke. They told him about it – hopefully.

Meanwhile the detectives were finding four pints of bourbon and tw quarts of gin in an automobile parked outside. Couch had another theory. It was that the automobile belonged to Ware.

Found inside the building were cigarets which Couch has an idea are made of marihuana. They were in a case, he said, which contained the name of one of the employes.

He arrested everybody, the asserted proprietor, the orchestra, the waters – and the customers. In all 41 went to city jail. 18 of them Negro men and nine of them white women with white escorts. Two patrols wagons made two trips.

Down at the jail, 40 were booked on charges of being found in a disorderly house. Ware was charged with being the keeper. Everybody, including Couch, was crestfallen to discover that the statutory bail for the 41 was $200 each. But obligingly, Couch and the jailors, with the sanction of a judge, soon fixed it so that only Ware had to put up $200. Last night all the rest were free on $25 bail each.

This may be an important paragraph:

The one-man morals squad said the Harlem Breakfast Club had first upset him when he quietly scrutinized it a week ago. He said he noticed that although white men were refused admittance unless accompanied by girls, stag Negroes got in. He though that was discriminatory and decided to do something about it.

Coverage by the Minneapolis Spokesman pointed out that all the white people arrested, male and female, were customers, while all the black people in the place were all black men and were all either employees or musicians. It was also argued that the press played up one officer’s account that there was a mixed couple dancing together, but there was no law against this activity, prejudice was behind the raid. (August 16, 1940)

The trial was quick – everyone was tried together. There was much discussion of the definitions of the terms “tippling house” and “disorderly house,” and many different accounts of why people were there and what they were doing. On Monday, August 19, 1940, Ware was sentenced to 90 days in the Workhouse for being keeper of a disorderly house. He was give a stay to September 9 to appeal, and continued his $200 bail. On September 25, 1940, his motion for a new trial was denied and he was ordered to serve his 90 day sentence.

The other 40 defendants were fined $5 each for being found in a disorderly house. His decision was partly based on the fact that people had been dancing despite the fact that Ware had no dance hall license, and that liquor was found in the kitchen and in Ware’s car, parked nearby.

On August 30, 1940, Ware was denied permits for food, cigarettes, and soft drinks, basically putting him out of business.

And there’s this, found by my friend Melinda Russell:

Lookie, Harlem Operators, Minneapolis Cops are Mean

Seventeen Negroes, 14 white men and nine white women were in the net of the raid by the police department here Tuesday which was launched as a drive against all-night, non-licensed liquor selling clubs. The raid was staged on the Harlem Breakfast Club, a black and tan layout. All the prisoners got fines of $5 each. (Amsterdam News, September 7, 1940)

1941

CLUB DE LUXE

It says here (perhaps in ads in the Minneapolis Spokesman) that the Club De Luxe opened in January 1941.

IT’S A RAID! NO. 3

But it was the Harlem Breakfast Club that was raided on September 12, 1941. The Minneapolis Star Journal published a big front page headline:

4 Nabbed in Harlem Breakfast Club Raid Given 90-Day Terms

The raid started at 2:20 am, led by morals squad leader Elmer Hart. Hart was denied admittance and had to break the glass on the front door to get in. There were 25 to 30 black and white patrons in the club at the time of the raid.

Three men pleaded guilty to selling liquor without a license, and one pleaded not guilty and was found guilty. It’s a little unclear whether the raid and the trial were on the same day?

1942

RAID 3 AND YOU’RE OUT

On April 6, 1942, the City Council’s health and hospitals committee denied an application for a license at the Highland Breakfast Club, 128 Highland Ave. Either this is a typo and should be Harlem Breakfast Club, or someone is trying to carry on with a slightly different name. Whatever the circumstances, it’s over.

AFTER BREAKFAST

128 Highland had a busy life after the Harlem Breakfast Club.

1943

NEW PALMS CAFE

On January 15, 1943, the Minneapolis Spokesman published an ad that the New Palms Cafe was Now Open at 128 Hyland, promising good food, music, and entertainment. The ads ran through February 12, 1943.

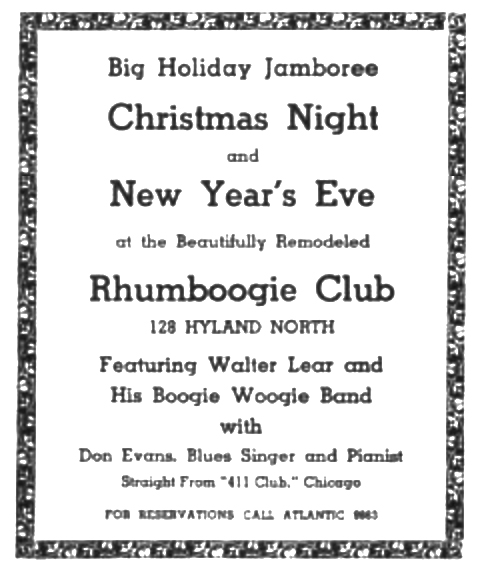

THE RHUMBOOGIE CLUB

The Rhumboogie Club opened on June 15, 1943 – “You’ll Enjoy Yourself.” The name apparently originated in a song that the Andrews Sisters performed in their screen debut in “Argentine Nights” (1940). The Rhumboogie Club in Chicago was located at 343 East 55th Street, opening in April 1942 and partly owned by boxing champion Joe Louis. There was also a Rhum Boogie Club in Harlem in 1943. Unless there was something in between, the Minneapolis Rhumboogie lasted from June 1943 to 1945.

Minneapolis Spokesman, December 24, 1943, via James Orndorf. Never mind the spelling.

Minneapolis Spokesman, December 24, 1943

Minneapolis Spokesman, via James Orndorf

1945

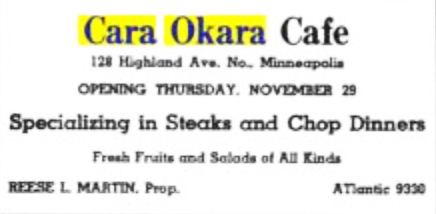

The Cara Okara Cafe opened on November 29, 1945. Reese L. Martin was the proprietor. The ad below ran on November 30 and December 7, 1945.

Minneapolis Spokesman

1947

SAM’S BAR-B-Q

Samuel D. Gransberry was the proprietor of Sam’s Bar-B-Q, and on Sunday, May 4, 1947, Sam was arrested and charged with selling liquor without a license. Also arrested were 15 customers of Sam’s, charged with violating liquor laws. Sam was released on $200 bail. He was eventually given six months probation.

Then on September 8, 1947, Robert Glenn was sentenced to 90 days in the workhouse for selling liquor without a license. The name of the place was not given, but 128 Highland was described as a night club and barbacue place. (sic) In 1948 a Robert Glenn was working for A.B. Cassius.

The building was listed as a cafe for sale in September 1947.

VFW

The Johnny Baker Post 291 of the American Legion used the building from at least July 1948 to October 2, 1953.

1953

In May 1953 it was advertised for sale as a vacant rooming house.

1957

The building was demolished in 1957.