Cotton Club

718 Sixth Ave. No.

Minneapolis

This is the story of 718 Sixth Ave. No. and the many night clubs that inhabited the building.

EARLY BUILDING HISTORY

In 1906, a store formerly located at 701 Sixth Ave. N was moved on the property. It was moved off the property in 1910.

In 1910, a 24’ by 80’ frame movie theater was built on the site.

In 1918, the theater was altered and made into an auto shop.

Sometime between 1918 and 1922, that building was demolished.

In December 1921, a 25’ by 90’ brick store was built. An identical addition was built two weeks later; presumably the second story.

On March 31, 1922, a group of black citizens presented a petition to the City Council asking for the right to open a theater at 718 for the exclusive use of blacks. A counter petition was filed by property owners claiming that an exclusive theater was not needed.

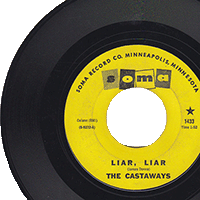

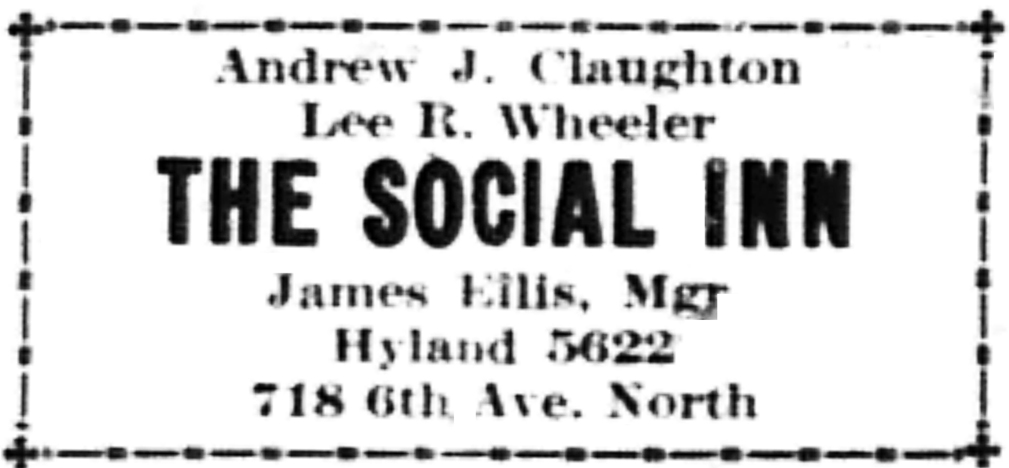

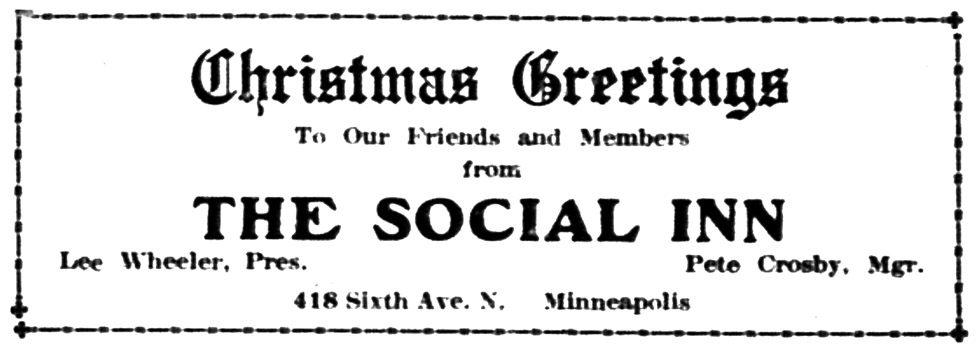

THE SOCIAL INN

In August 1922, the building hosted the Social Inn. The Social Inn was owned by Andrew J. Claughton and Lee R. Wheeler, with James Ellis, Manager.

Did it move to 418 Sixth Ave No. by December 1922, or was that a typo?

Permit card entries describe the building as a store through 1923.

In October 1923, the building was the home of the Northwestern Waiters’ Club. A scandal appeared when policemen were accused of drunkenness and tipping members of the club off of an upcoming raid.

In November 1923, a man named H.M. Robe was given 30 days in the workhouse for running a gambling house in the building.

In October 1924 – 1930, the building was the headquarters for the Northwestern Porters and Waiters’ Club, “a Negro rendezvous.” The Club was in the news in 1924 because a crap game had ended in gunfire.

An article dated July 18, 1925, reported that the Union Co-operative Bakery would open in the building on that date. The Permit card bears that out.

THE COTTON CLUB

Named after the famous Cotton Club in New York, this Cotton Club was on Sixth Ave. No. in Minneapolis – not to be confused with the Cotton Club in St. Louis Park, or the Cotton Club in St. Paul. This was the most famous, for its placement “On the Avenue,” and for its infamous deadly shooting in 1928.

The Cotton Club was a “Chicken Shack.” Chicken shacks were common during Prohibition and this one had chicken and dancing and fighting all night. A newspaper account reported that the Cotton Club was operated by William Pugh, “a Negro.” It is unclear when the Cotton Club opened. It was one of many “Black and Tan” clubs on “The Avenue” that featured entertainment, late nights, gambling, and illegal spirits (or at least setups for your own).

THE SHOOTING AT THE COTTON CLUB

The following account comes from several sources: contemporary newspaper accounts, research by Jeff Neuberger, and a contemporary account by the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis:

On February 3, 1928, at about 4 am, Jack Sackter, riding in a taxi, flagged down two Minneapolis Police Officers. James H. Trepanier, age 32, had been a patrolman for five years. He had been cited for bravery in the capture of a bandit in 1924. He had served as a motorcycle policemen prior to his transfer to the North Side precinct.

Patrolman Bernard Wynne, age 39, was a World War hero. He had been wounded in a gunfight two years earlier in which Minneapolis Police Sergeant Michael Lawrence was killed, and Wynne had been shot three times in the legs.

Sackter told the officers he had been assaulted by a group of men in the Cotton Club. There were two versions of what caused Sackter to bring the police to the club. Sackter maintained he was friends with Valencia Nay, one of the entertainers at the club, and as he spoke to her at his table, the notorious bootlegger Isadore Blumenfeld (aka “Kid Cann,” erroneously identified as his brother Harry Bloom in police and news reports) told Sackter to leave her alone.

Another man in Cann’s party, Verne Miller, struck Sackter with a gun. Miller, a former Sheriff from Beadle County, South Dakota, had become a bootlegger, bank robber, and embezzler, and had quite a bit of money on him. The second version is that Sackter said something very offensive to Ms. Nay and Miller hit him for insulting her.

WHAT HAPPENED?

The following is a contemporary account of what happened, from the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis:

Patrolmen Trepanier and Wynne walked into the cabaret, drew their pistols, and commanded patrons of the cafe to line up to be searched for pistols.

“Call the wagon while I search them,” Officer Trepanier told Officer Wynne.

As Trepanier started to search the first patron in line and Wynne walked to the telephone, a table was overturned in one end of the cabaret. Five men were standing around the overturned table.

There was a tense moment while the two police and five men glared at each other. Then, with a sudden movement, one of the men drew a pistol and opened fire on the officers. In a second several other pistols were drawn in the crowd.

At the first shot, Officer Trepanier fell to the floor, severely wounded, and after two or three

more shots, Office Wynne staggered when a bullet struck his leg. Both patrolmen returned the fire.

For a moment pandemonium reigned. Pistols barked and filled the small hall with their roar.

Bullets thudded into the walls, splintered chairs and tables and broke out windows.

Women and men alike screamed, dodging, scurrying, and fighting to cover. Patrons turned over tables and cowered behind them, fear in their eyes.

Officer Trepanier, stretched on the floor, groaning from his wounds, braced his right arm

with his left hand and emptied his pistol at armed men in the place.

Officer Wynne only staggered when a bullet struck his leg. He emptied his pistol at the crowd and, despite the pain of his wound, brought them to order. Waving his empty pistol at the disordered mob, he commanded:

“Now all of you line up here and be quiet.” He called the patrol wagon and loaded the thirty remaining patrons of the cabaret into it, directing that they be taken to police headquarters.

At headquarters, all but eight were released. These eight were lodged in jail and questioned after three pistols were seized from them.

Detectives and gun squads were sent out through the city seeking other persons believed to have escaped during the gunfight. On a tip from a man whose car was found standing in front of the cabaret, detectives were sent to St. Paul in search of three men believed to have been companions of the man said to have started the shooting.

AFTERMATH

Officer Trepanier was the most seriously injured. Miller’s bullet had struck him in the right side of the abdomen, ripped a 3-inch laceration in the liver, tore off the top of the gall bladder, lacerated the stomach, severed the duodenum, smashed through the right kidney, and hit the fourth lumbar vertebrae, producing a hemorrhage in the spinal cord and stopped just under the skin on the left side. More than a dozen police officers lined up to give blood to save his life. Officer Trepanier was in the hospital numerous times. After he had partially recovered, he opened a jewelry store at Lake Street and Chicago Ave. South, but soon afterward went back to the hospital. Later, he moved his jewelry repair bench to Veterans’ Hospital where he designed and made jewelry and repaired watches when able to sit up. He waged a ten-year fight against his paralysis, but he had grown steadily worse for more than a year, and finally succumbed on September 20, 1938, at the U.S. Veterans’ Hospital. He was 42 years old when he died. He was survived by his wife and two daughters.

On May 15, 1938, Officer Bernard Wynne came home after assisting at a double drowning in the Mississippi River at 51st and Lyndale North and committed suicide.

The Grand Jury indicted Miller, Blumenfeld, Robert Kennedy, and R.L. Lawler on first degree assault charges.

Verne Miller was never apprehended for the shooting of the two officers, despite a manhunt with 1,500 fliers distributed, mostly over the Northwest. Verne Miller would be found murdered by other gangsters outside of Detroit on November 28, 1933.

One of Wynne’s shots hit Kid Cann in the thigh as he ran for the door. Kid Cann was taken to General hospital, as were the two police officers. Kid Cann was held without charge for days and then held for trial, accused of participating in the gunfight, but in October 1928, Hennepin County Attorney Floyd B. Olson dropped the prosecution, citing the differing stories about the relationship between Sackter and Nay.

Kennedy and Lawler were not captured until late April. One was a Sioux Falls, South Dakota, fight manager and one was a former St. Paul barkeeper.

ABOUT VALENCIA NAY

Ever the intrepid historian with insatiable curiosity, Jeff Neuberger dug deeper into the story of the cause of the ruckus, Ms. Valencia Nay. I considered doing this myself, so I’m glad he beat me to it!

News stories at the time list her as living at 538 James Ave. N. Checking records, he also found a Hurl Nay at that address. The Nay family was originally from Missouri: Hurl, his twin brother Harry, their older brother Lawrence, and Lawrence’s wife Gladys. Valencia may have either been a sister or Hurl’s wife. They were one of many acts that performed a musical comedy called “Shufflin’ Sam from Alabam” that toured all over the country. The show included the Creole Chorus, a group of female singers, and the Memphis Blue Demons Jazz band. There were also dancers doing the Charleston or the Black Bottom. People came to see the show for the comedy, the music, and the pretty girls.

Unfortunately, the Nays met a bad end. On March 15, 1934, while driving home from a performance at the Heidelberg Club in Flint, Michigan, about 2:15 am, the Nay brothers’ car was struck by a Great Western train. Lawrence, Gladys, Hurl, and Harry were killed. A Gipsie Nay was injured, as was Minnie Smith, 19. There was no mention of Valencia.

CHANGES

As a result of the shooting:

- Police Chief Frank W. Brunskill ordered that “entertainments in cafes and night clubs be brought to a close at midnight hereafter.” The order applied across the city, not just on 6th Ave. No. where “a number of all-night restaurants operate.” “Many of the eating establishments cater to a night trade a no hour for their closing can be set, Captain Nick Smith of the North side explained. But singing, dancing and the like will have to stop at midnight, according to the order.”

- Brunskill ordered the Cotton Club establishment closed and declared his intentions to close every similar place in Minneapolis. Meanwhile, every cabaret in the city was under police observation.

- On April 17, 1928, the City Council revoked the license of Horace Pierson, first floor of 718 Sixth Ave. N, formerly known as the Cotton Club. Presumably this was his restaurant and dance hall license.

- A City Alderman proposed an ordinance requiring that curtains and screens be removed from all chicken shacks, so as to permit a view of the interiors from the street.

PANAMA CAFE

April 1928: Serving chicken, Chinese food, entertainment. Presenting Warren & Ellison, direct from Plantation Cafe, Chicago. Best Music in Town.

MAX FELD, GROCERIES:

Evidence of Feld’s grocery store at this location can be found from December 1928 to June 1932. Feld moved his store around to many locations in the area during this time. In the 1932 Minneapolis directory, Feld is listed as a grocer and the second floor is listed as vacant.

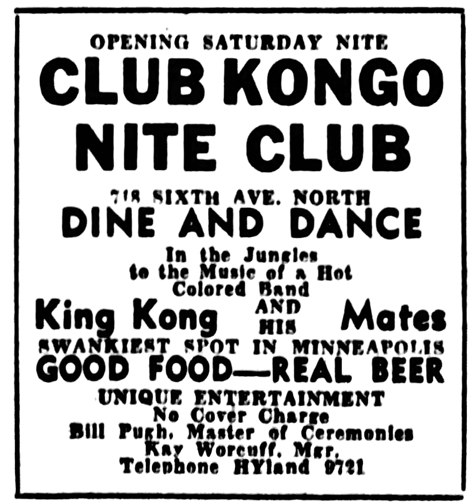

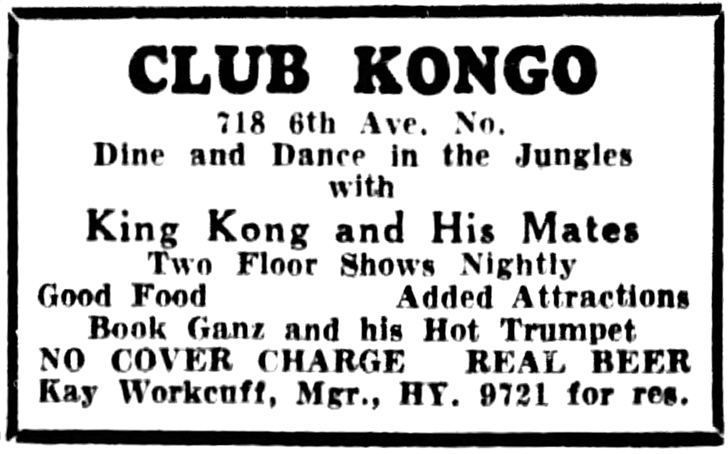

CLUB KONGO

Beer became legal on April 7, 1933, and the Club Kongo opened on April 30, 1933. Kay Worcuff was listed on the ad below as the manager, with Bill Pugh as the M.C. Same William Pugh who was the operator of the Cotton Club? The movie “King Kong” was released just about the same time, inspiring the theme for this “Nite Club.”

The presence of Rook Ganz meant this was a going concern!

But on a raid on a number of night clubs on January 14, 1934, proprietess Thera Rutherford was arrested for violating the tavern closing ordinance. She was fined $50 for staying open after 2 am, and her beer license was revoked on April 4, 1934.

CLUB MOROCCO

The Club Kongo was followed by another African-themed club called Club Morocco. The Grand Opening was on September 15, 1934. “Hotsy Totsy!” Music by the Club Morocco Band, the Northwest’s Favorite Night Club Entertainers. Another Grand Opening announced for December 13, 1934. The owner was Hamlet “Kid” Rowe, according to the ad below.

According to the ad above, the cook was Tiny Holder, formerly of the P&S Chicken Shack. After the Club Morocco was gone, Tiny went back to the P&S:

END OF 718 SIXTH AVE. NORTH

The north side of Sixth Ave. No. was demolished in 1938 for the Sumner Field public housing project. The demolition permit for 718 Sixth Ave. North, with the Club Morocco sign still in the window, was dated September 15, 1938.

The following are a few photos showing the building in various stages before demolition. The first one is unfortunately undated but must be in the early days of the project since the buildings on either side are still there. Thank you to Jeff Neuberger and Alan Slacter for these images.

We wondered what was on that sign that was hanging from the pole on the second floor, but the photo I had was too low resolution to see it clearly. But then we found the original on the Hennepin County Library website, and discovered that it was a gorilla, hanging from the pole, left over from the Club Kongo days back in 1933-1934. What a find! Here’s a close-up.

There is a note on the array of photos taken in 1938 that may indicate that 718 was the last building to be demolished on the north side of the street. Below is a photo of that sad day, September 16, 1938: