Snoose Boulevard Festival

West Bank

Minneapolis

The Snoose Boulevard Festival was held in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood from 1972 through 1977. In the late 19th century Cedar Avenue became known as “Snoose Boulevard,” a nickname often given to the main street in Scandinavian communities. The term derived from the residents’ fondness for snus (snuff), an inexpensive form of tobacco. The event, which celebrated the area’s Scandinavian past, featured the music, food, and arts of the immigrants who had once lived there. It also highlighted the careers of Olle i Skratthult (Hjalmar Peterson), Slim Jim and the Vagabond Kid (Ernest and Clarence Iverson) and the Olson Sisters (Eleonora and Ethel Olson).

Much of the following comes from the Minneapolis Bridgeland News:

1971

In 1971 accordionist and folklorist Maury Bernstein* wanted to re-create the Scandinavian music and vaudeville shows that appeared nightly on the West Bank. He asked Swedish singer-actress and onetime Twin Cities Scandinavian radio host Anne-Charlotte Harvey, who had recently moved to San Diego, California, to come back to sing with him for two or three concerts at the Cedar movie theater, now the Cedar Cultural Center. The shows were very popular, selling out all 1,500 seats.

1972

Bernstein enlarged the shows the following April, drawing 14,000 to what to what was the first of six annual Snoose Boulevard Festivals. “The young shop owners and residents so far have shown delight at the idea of welcoming back old residents,” fulfilling one of his goals, he told a newspaper at the time. His other goal was to “accumulate knowledge about the area’s heritage.” It took place on the entire Fifth Avenue, and all the businesses decided to contribute to the festival on their own.

Harvey recalled accordion contests at the Viking Bar, displays of Scandinavian items for sale in the windows of Samuelsons’ store, a smorgasbord at a Japanese restaurant, and a comic storytelling contest at Dudley Riggs.

“They came in big busloads from Northern Minnesota, Bemidji. There were Finns from the Iron Range who came down to dance,” Harvey said. “The Cedar was too small for the concert. So we were allowed to move to Rarig [Center] which was just built!”

There were usually four musicians, five at the most. The core group was lead singer Harvey, accordionist Bernstein, with fiddler E. Craig Ruble, Ron Colby (real name: Corbjornsen) on banjo, and, the first years, guitar and mandolin player Stephen Gammell. Bill Hinkley joined later.

Harvey worked in theater and creatively and authentically dressed the performers. She wore Swedish, Italian and other folk costumes, along with old scarves from Sweden. But “somebody had to get these guys something to wear. The guys didn’t have anything that looked old-time or immigrant or anything. I found some things in thrift stores and I brought a few things from San Diego, rented costumes from the Guthrie and then the theater at the U.”

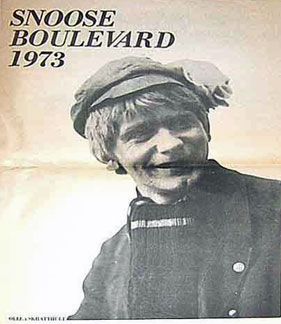

1973

The second annual festival in 1973 was broadcast live on 102 stations as a special (98-minute) program on National Public Radio’s “FESTIVAL U.S.A.” series. The nonprofit Olle i Skratthult Project formed that year when research turned up Hjalmar Peterson, whose stage name meant “Olle from Laughtersville,” a tramplike character with a suitcase of money, out of which he paid all the expenses of the band. Bernstein told Hampl that Olle i Skratthult was “a cultural hero along Cedar Avenue and many other “Snoose Boulevards” across the country, especially after 1915, when he recorded “Nikolina,” the most popular Swedish song in America. It sold more than 100,000 records and was still on the juke box at the 5 Corners Bar, according to Hampl.

1974

The festival had a momentum of its own. By the third year, more than 100,000 people filled the streets during the festival. The old firehouse (now Mixed Blood Theater) was a hot spot for old-time dancing, with bands trading off every few hours. Harvey noted that this was likely the year that the festival “got too big, too fast.” In 1974 the festival incurred debts that took the rest of the festivals, through 1977, to pay off. Tired of debt and battling local authorities about things such as numbers of visitors allowed, the festival team called it a day. There had also been criticism of the festival, particularly from the former director of the Swedish Institute who objected to calling attention to the “seamy side” of immigrant history.

Towards the end, Harvey said, developments in the neighborhood caused the area to change “very quickly. The firehouse changed and Mixed Blood theater took over, and no longer could we use the space for old-time dancing. The University had expanded, and there was a different feel in the area. And some of the old-timers had died. We caught the last wave of the real old-timers that did come and did dance and just loved it. But if you tried to revive it 10 years after that, there wouldn’t have been anybody.”

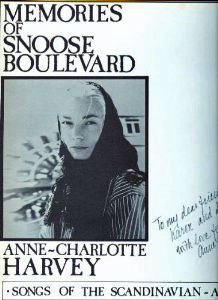

By then, Bernstein had become “Mr. Snoose Boulevard,” producing three albums of Harvey’s music: “Memories of Snoose Boulevard,” “Return to Snoose Boulevard,” and “Scandinavian in the New Land.” These albums included folk tunes, emigrant ballads, hymns, waltzes and comic songs.

Hear the songs here courtesy of the Library of Congress.

1976

1978

On February 3, 1978, the Minneapolis Tribune published a notice from Bernstein announcing that there would be no Snoose Blvd. Festival that year. Reasons given were the unavailability of some key staff and performers, and “unsettled Cedar-Riverside neighborhood conditions.”