Mr. Lucky’s

2933-35 Nicollet Ave.

Minneapolis

All ads on this page are from the Star Tribune unless otherwise noted. Additions, corrections, and stories are appreciated; please contact me.

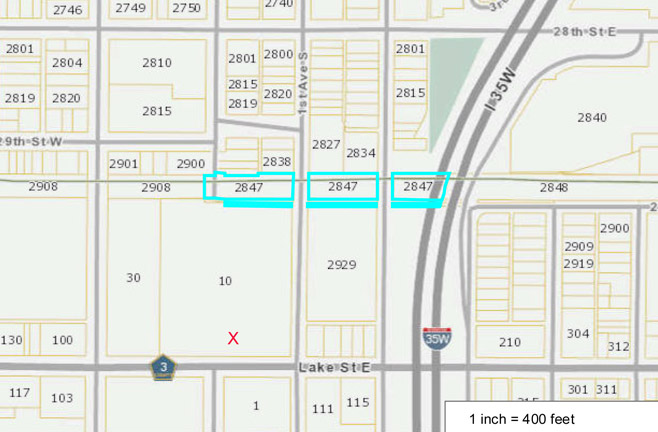

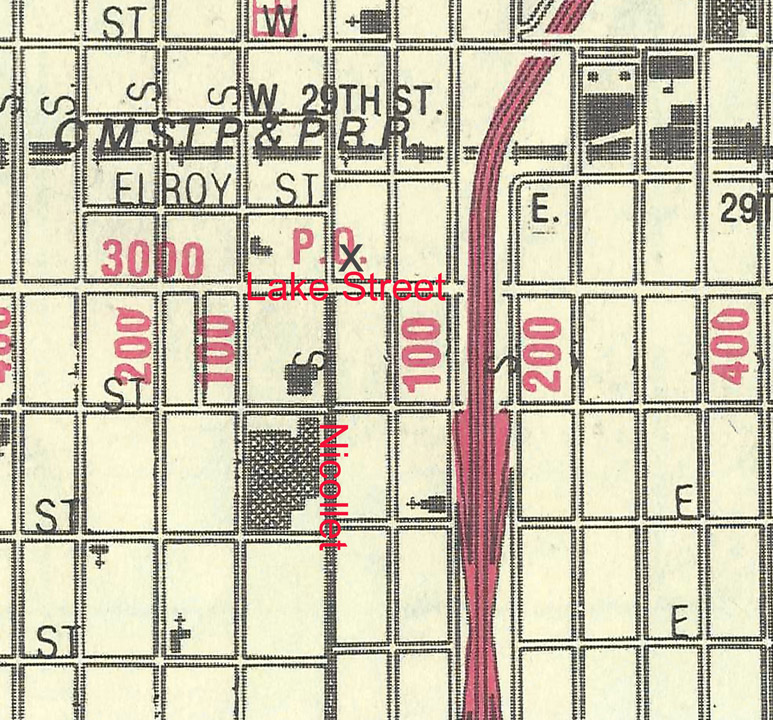

This building was a lively spot for decades. But don’t go looking for it or you’ll find yourself inside the K-Mart where Nicollet Ave. used to be. Here’s an old map, marked where I think it was:

The space was often subdivided in ways that are a little mysterious, but I’ll do the best I can to reconstruct the different, wonderful places and activities that took place here.

HOTEL AND STORE

The site’s earliest history can be found in the permits and inspections records at Hennepin County Library Special Collections. In March 1886 a permit was taken out to build a wooden structure to be used as a store and hotel. Listings for the hotel continued until 1892. An ad to rent “a very pleasant suite of two rooms on second floor” and a “barn for storage or auto space” at this address appears in 1910.

SCHULSTOCK SHEET METAL

A permit for an iron electric sign was taken out in March 1917, no doubt for this business.

Nevertheless, a permit to demolish the barn was taken out in July 1917 and two dwellings in May and September 1918.

DAY-NITE GARAGE

In April 1919, a building permit was pulled to build a brick and concrete private garage measuring 140 ft. by 123 ft. Cost was estimated at $15,000. By garage this meant a car dealership. In 1923 the owners requested permission to install a gas pump.

In September 1924 a permit to build an 18 ft. by 56 ft. addition was pulled. In 1925 Day-Nite Garage and the filling station were owned by R.J. Johnson.

INDOOR GOLF COURSE

In September 1930 John A. Nelson received a permit to run an indoor golf course. Permits to do the necessary electrical and plumbing work and to erect a sign were pulled in October. This was probably only there a short time – found only two mentions in the Strib.

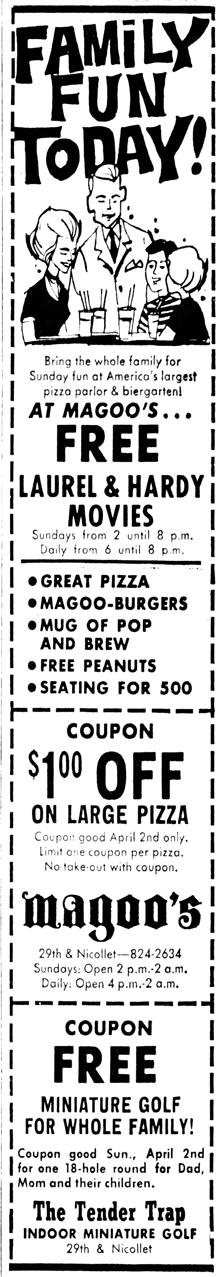

Not to be confused with the 18-hole Tender Trap, a Mini-Golf place listed at 29th and Nicollet, next to Magoo’s. References to this place appear from December 1966 to November 1967.

TRIANON DANCE HALL

The first of several dance halls was conceived in December 1931 when Melville J. Nelson applied for a permit for dance hall. Another notice says that Mrs. Nellie C. Little installed new floors and replaced the roof on the building at a cost of about $3,000. This turned out to be Minneapolis’s own Trianon Dance Hall!

The only other ads for the Trianon found were dated March 19 and an Opening Dance on August 27, 1932. It may be that it was closed during the summer months – before air conditioning, ballrooms were simply too hot. That August the holder of the dance hall license was Ernest G. Bjorklund.

DANCELAND

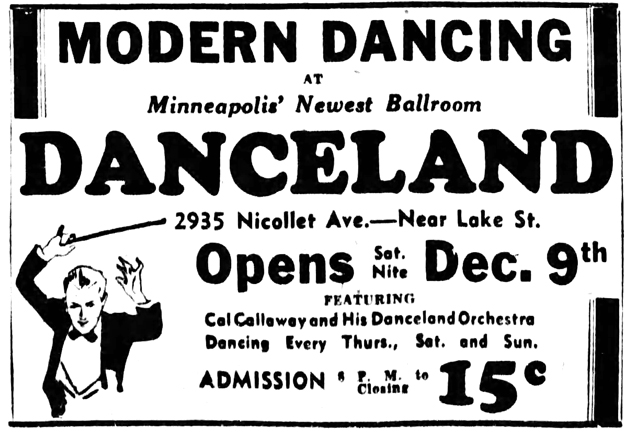

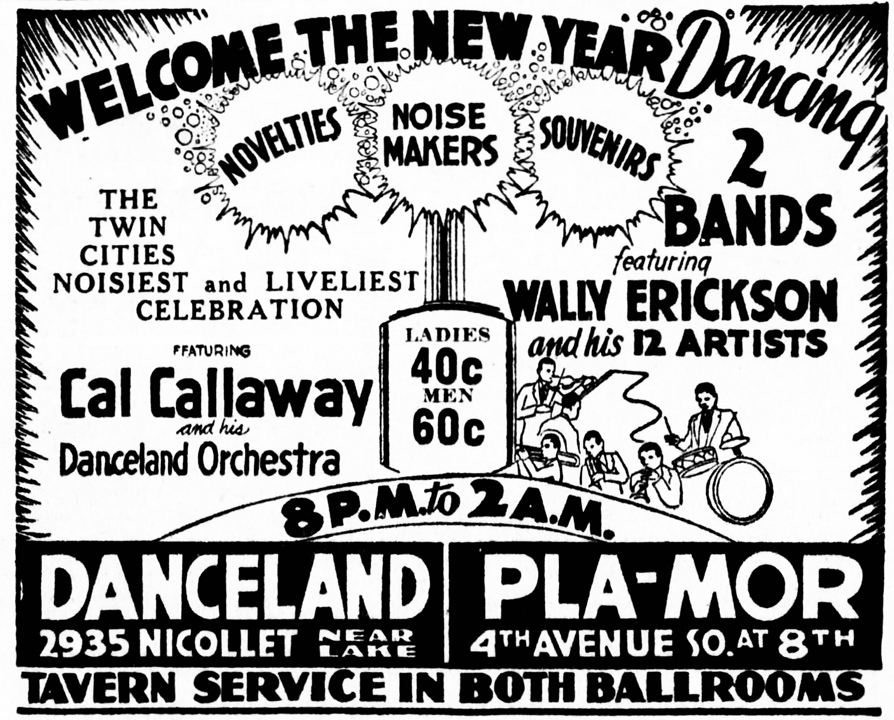

Further alterations and repairs were done in the spring of 1933. Plumbing for a cafe was added that June. A liquor license (probably for early post-Prohibition beer) was obtained in May 1933. A new iteration called Danceland opened on December 9, 1933, featuring the music of national sensation Cab Calloway. Oh wait! That’s Cal Callaway! More electric work for the dance hall and a new iron electric sign were added in January and February 1934.

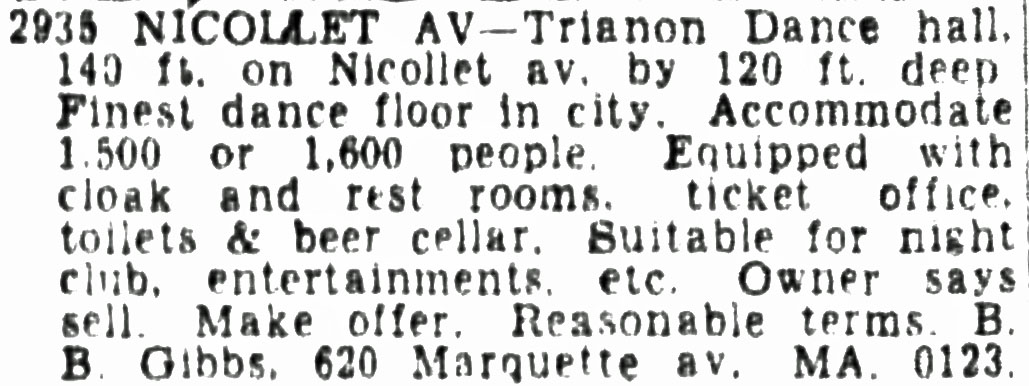

Unfortunately, Danceland, which was apparently still owned by the Trianon people, did not succeed. On May 12, 1935, an ad appeared:

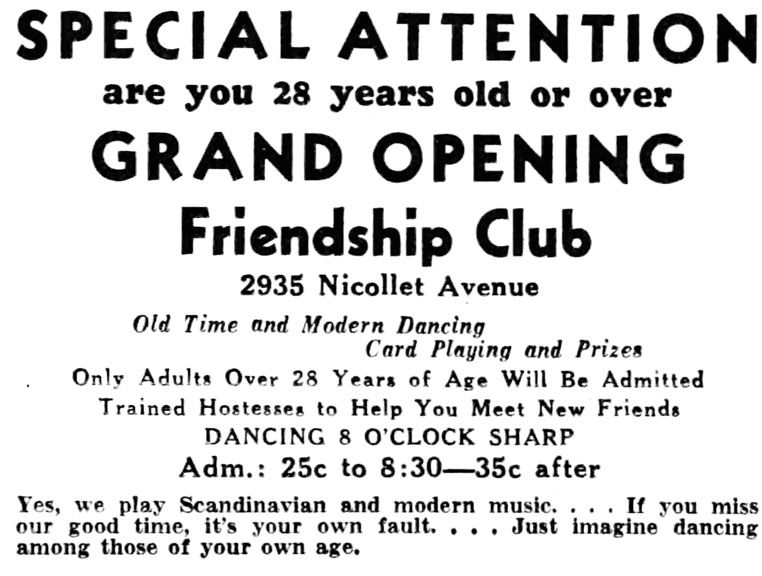

FRIENDSHIP CLUB

The Friendship Club was the brainchild of Frank “Smilin’ Bob” Kenney and his wife Kathryn. Kenney was originally from St. James, Minnesota, and had served in WW I. In 1931 [1929] he was a night club waiter in Milwaukee and figured that there were lots of people who couldn’t afford a $3, $4, or $6 evening, but would still like to have a place to dance at a reasonable price. He also felt for lonely people who had nobody to dance with or felt that they were too old to dance with the youngsters. He invited a group to his mother’s house to dance, and as it grew it moved to a hall. First called the Lonesome Club, it later changed to the Friendship Club.

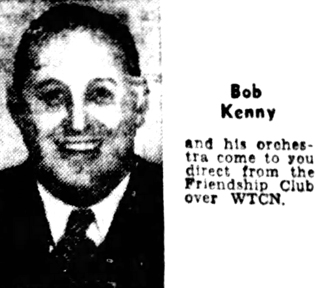

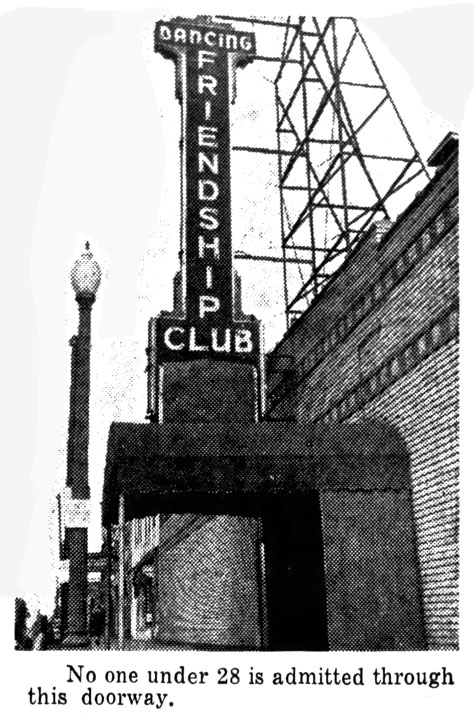

Bob brought the idea to Minneapolis in 1935; wife Kathryn stayed behind for a year in Milwaukee. Kenney’s orchestra presided over the immense dance floor starting in October 1935. Kenney had a huge collection of arrangements stored in a special closet. The Friendship Club apparently occupied the entire building from 1935 to 1952.

There were lots of rules at the Friendship Club:

- The Club was only open to people over 28 – the unusual number came about because women didn’t want to admit they were over 30!

- No liquor was allowed – anyone caught nipping was given the boot. (3.2 beer was available)

- No cutting in

- No jitterbugging (a sign said “Positively No Fancy Dancing”)

- Applicants had to have references and be voted in by a committee.

- “Positively No Two Ladies Dancing Together During Get Acquainted Dances”

- Men must wear ties.

- No tables reserved

Its “Get Acquainted” dances were described by Cedric Adams:

There are two of them during the evening. The dance lasts for about 20 minutes, and starts out with a march which is followed by a waltz, a circle two-step and a Paul Jones. You start out with your own partner, Bob blows a whistle. That means all dancing stops for a second or two. The couples promenade in twos, fours, or sixes and then girls step back one partner. The new partners greet each other, shake hands, make themselves acquainted, and the dancing is resumed.

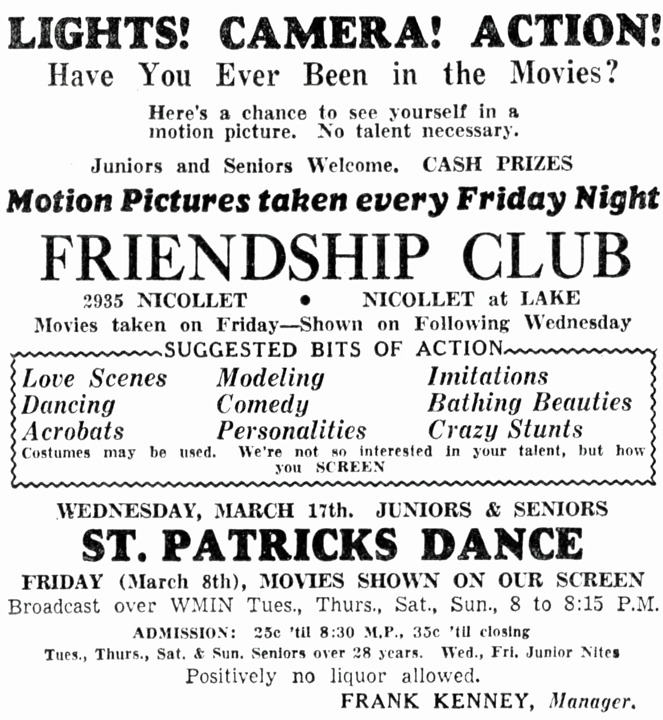

Kenney’s orchestra and booming voice were broadcast over a variety of radio stations for many years. The club was open Thursdays, Saturdays and Sundays.

An overhaul at the dance hall came in May 1936.

1937

A Junior Friendship Club was announced in January 1937. The ad was quite wordy, and typically full of rules:

Every Friday night The Friendship Club sponsors a party for all the young people who will conduct themselves as ladies and gentlemen while at the club. Positively no liquor allowed, just good clean fun. Remember if you’re stuck up and not a good mixer, stay at home. We only want those who will join our get acquainted dances and dance with everybody. It’s just loads of fun. Membership cards free to anyone who is a good mixer; so check your conceit outside and be a good scout. Make every Friday nite your club nite, a party where Mother and Dad will be pleased to let you go. Music by Smiling Bob Kenney and his Troupe of entertainers playing both old tyme and modern music. Featuring The Television Queen, Amanda Snow, Friendly Voice of the Air, Mel Burlingame and that funny comedian, Moxie Ryan. Broadcasting WMIN 8:15 PM Tues., Thurs., Sat. and Sun. Are you coming, are you regular? Admission 25c until 8:30 35c to closing.

June through October 1937 saw a great deal of work done on the dance hall and cafe; this was when air conditioning was added. The ad for July 3, characterized as a Homecoming for Smiling Bob and his Orchestra, is hilarious:

All air-conditioned and redecorated. Cool! Boy, oh boy it is swell! The garden spot of Minneapolis. Don’t be Fooled, when your friends say it is hot, let’s go to the lake. The big mosquitoes will bite you if you don’t watch out. No mosquitoes at the Friendship Club and it is cool as a cucumber.

1939

On October 22, 1939, Cedric Adams did a full-page article on the Friendship in the Star Journal. By 1939 membership was up to 8,000.

1940

In May 1940, Cedric Adams reported that the Friendship Club merited a front-page story in Variety: “Big Coin in Lonely Hearts.” Stories were also being contemplated for Life and Time magazines. Membership was up to 9,000.

1944

Frank S. “Smilin’ Bob” Kenney, the founder of the Friendship Club, died of a heart attack in January 1944 at the age of 51. At the time of his death he was the secretary of the Nicollet-Lake Business Men’s Association.

1946

In April 1946 we learn from Will Jones that Frank Kinney’s widow has remarried and is now Mrs. William Brecheisen, still running the Friendship Club. She said, “We have tried clever vaudeville entertainment and novelty acts, but our customers don’t want that. They just want to dance and get acquainted.”

Jones:

The man fearing mayhem at the hands of jitterbugs finds dance acrobatics banned at the Friendship; hostesses find even taller partners for tall girls.

And – this is the specialty of the house – oldsters who might be termed “corny” by the ordinary dancehall clientele are encouraged to ply the steps of 20 years ago.

1951

By 1951 membership had grown to 10,000. Another Will Jones feature revealed that the place was monitored by two policemen and three other security officers. The dancehall was recommended to traveling salesmen by hotel personnel. It was open Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays. “Mrs. B” was a “plump redhead.” Thanks, Will!

A February 1953 ad mentions cash awards.

In 1959, Fridays were contest nights. And you could vote for the King and Queen of 1959.

1960

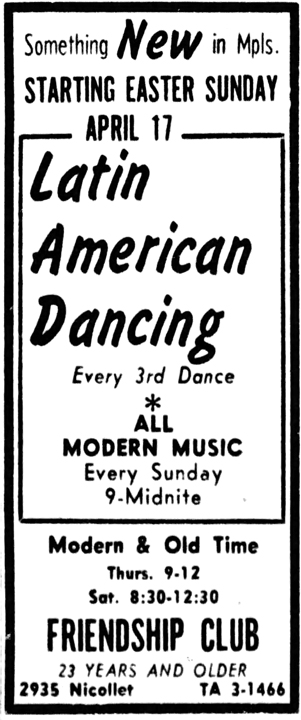

Now you can’t say that the Friendship Club didn’t keep up with the times. In 1960 Jerry Mayeron’s orchestra infiltrated the Friendship Club on Sunday and Thursday nights, playing the newly-popular Latin rhythms on Sundays and “a standard variety of dance music” on Thursdays. The regular band continued on Saturdays. Looks like the age limit went down, too.

Mayeron was replaced by the Tail Gate Six in May and June 1960 – no clues as to what they played. Dick Kast followed.

1961

THE NEW FRIENDSHIP CLUB: 1961

Times were changing, and so was the venerable Friendship Club. Or maybe all the old patrons had married each other. Or died. Anyway, the owners saw a need to appeal to a younger, livelier audience. In January 1961 the venue was recast as the NEW Friendship Club, and Friday nights were designated as teen nights. The concept of teenagers was kind of new then – before that, there were adults, young adults, and children.

After some generic “Teen Dance” ads, the first to name a band was on February 10, 1961, when the reliable, rockin’ Mike Waggoner and the Bops held forth at the FC.

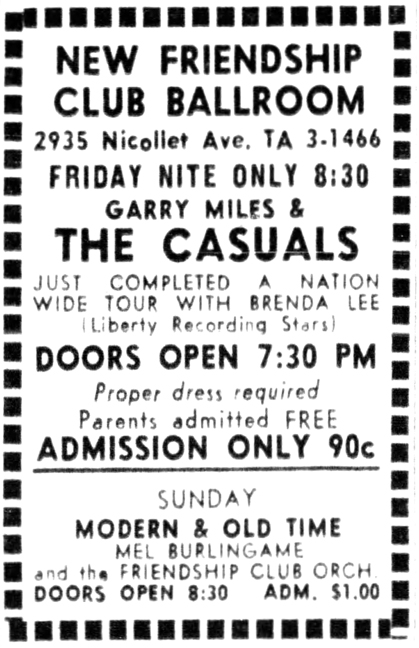

April 7: Garry Miles and the Casuals. Miles was one of four, count ’em, four artists who charted with “Look For a Star” in 1960. One of the others was one Gary Mills. Hmmm.

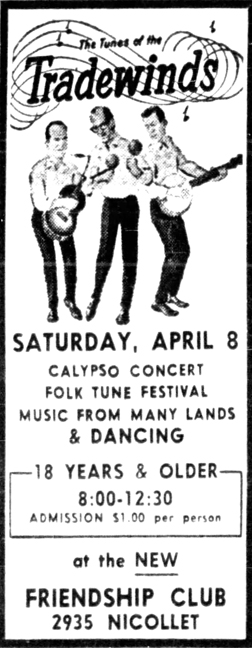

April 8: The Tradewinds. In an apparent new policy of trying to be all things to all dancers, the New FC hired a calypso/folk group to alternate with the old time dances and teen brawls.

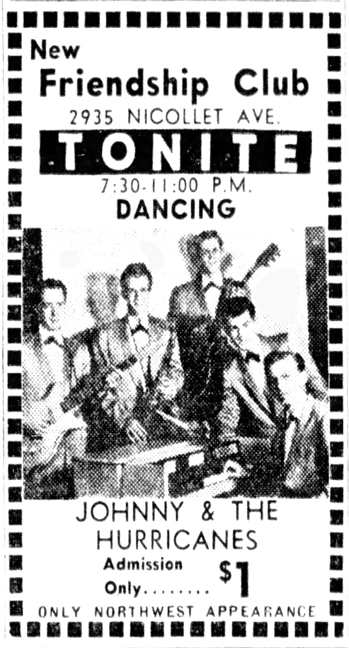

April 14: Johnny and the Hurricanes

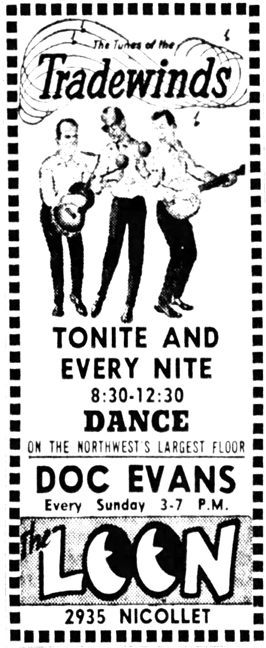

April 16: Doc Evans (Dixieland)

And that was the end of the Friendship Club. It had a good run.

THE LOON CLUB

In April 1961 the Friendship Club, which had drastically changed its format, morphed into the Loon Club. Will Jones noted, “The new owners there rushed to be the first to name a tavern after the state bird. All the signs proclaiming the myriad rules of the Friendship Club have been taken down, and the place is being redecorated gradually.”

1961

April 26, 1961: The first advertised group was the Tradewinds, a Calypso trio that had performed at the New Friendship Club. Even the ad was the same except that it had the new Loon logo. Doc Evans worked on Sundays.

June 1961: Will Jones reported that Augie Garcia had “abandoned Lake Minnetonka” and was at he Loon Club Tuesdays through Sundays, with long sessions on Sunday afternoons.

Jones also reported:

The place strives to live up to its new outdoorsy name with some outdoor atmosphere. The management has imported 10 large live trees, and also has scattered 300 pounds of green sweepings on the floor to give a grassy effect.

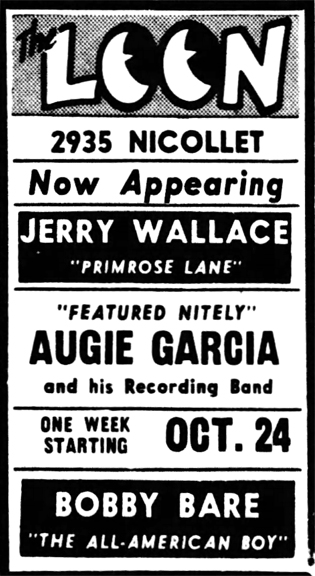

October 17 – 23, 1961: Jerry Wallace

October 24, 1961: Bobby Bare

A LITTLE BIT COUNTRY

Still trying out styles, the Loon started bringing in national C&W acts.

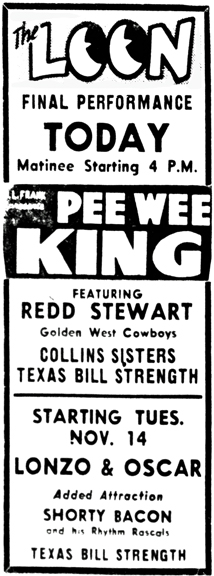

November 7 -12, 1961: Pee Wee King, the Collins Sisters, Redd Stewart, the Golden West Cowboys, and local favorite Texas Bill Strength.

November 14, 1961: Lonzo and Oscar, Shorty Bacon and his Rhythm Rascals, Texas Bill Strength

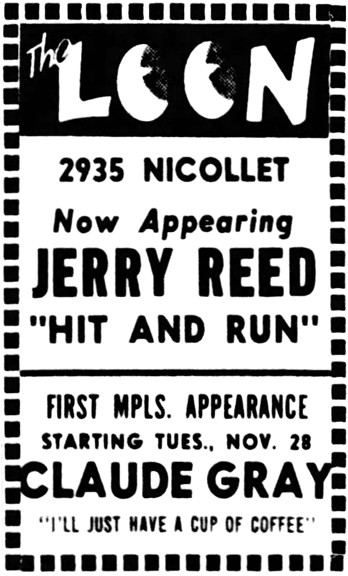

November 25, 1961: Jerry Reed

November 28 – December 3, 1961: Claude Gray, Jan and Patti North

December 4, 1961: The Loon Club instituted Scandinavian Night on Mondays, featuring Louie’s Twin City Concertina Band

December 5 – 10, 1961: Wanda Jackson

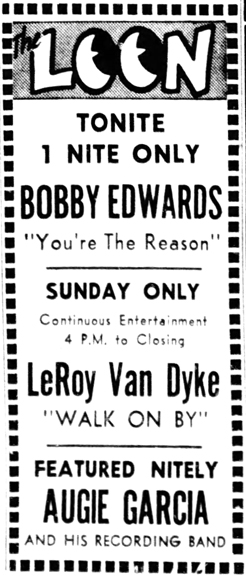

December 16, 1961: Bobby Edwards

December 17, 1961: Le Roy Van Dyke

1962

A LITTLE BIT ROCK ‘N’ ROLL

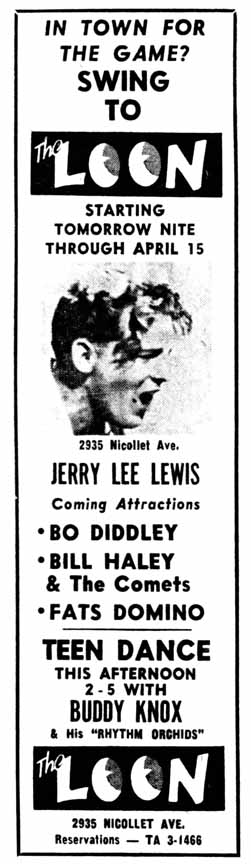

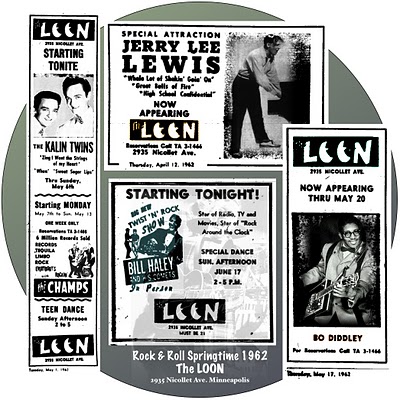

Maybe the Loon couldn’t compete with the Flame, so the owners took a different tack, bringing in an incredible stable of national rockers, with local hero Augie Garcia as the house act.

February 3, 1962: Battle of the Bands – Roscoe and the Green Men vs. Augie Garcia

February 5 – 10, 1962: Bill Haley and His Comets

February 12, 1962: Tony and the Knights (“Peppermint Twisters”)

February 17, 1962: Tony and the Knights (“Peppermint Twisters”) vs. Augie Garcia (“Taco Twisters”)

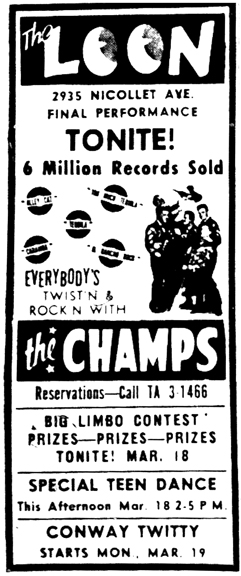

March 12 – 17, 1962: The Champs

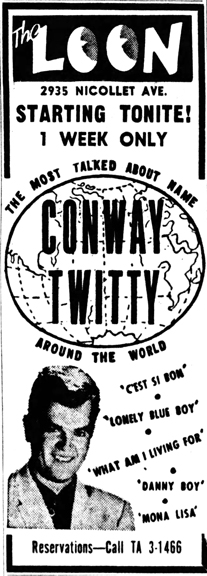

March 19 – 24, 1962: Conway Twitty. Will Jones reported that Twitty had developed a nightclub act, but the “cavernous interior of the Loon Club” was not conducive to the material, so he and his group mostly played music for dancing, including the twist, an inescapable phenomenon in 1962. On Saturday, March 24, the Loon featured Twitty in a special Tournament dance for the kids in town for the Boys’ High School Basketball Championship.

March 25, 1962: The Durados

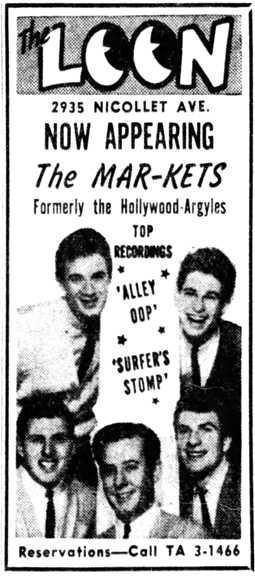

March 26 – April 1, 1962: The Mar-Ketts (“Formerly the Hollywood Argyles”). Who knows who these guys were, since both the Hollywood Argyles and the Markettes were studio groups. But I like their skinny ties.

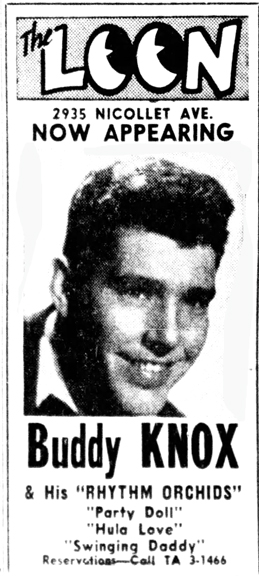

April 2 – 8, 1962: Buddy Knox and the Rhythm Orchids

April 9 – 15, 1962: Jerry Lee Lewis

May 1 -6, 1962: Kalin Twins

May 7 – 13, 1962: The Champs

May 14 – 20, 1962: Bo Diddley

* The Star and Tribune went on strike in May 1962, and the slack was taken up by the Minneapolis Daily Herald. Robb Henry put together the collage of ads below showing the 1962 ads that were printed in the Herald.

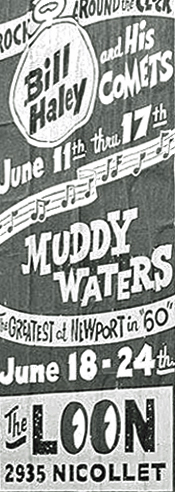

June 11 – 17, 1962: Bill Haley and His Comets. Not sure where this ad came from.

June 18 – 24, 1962: Muddy Waters

DOWN TO EARTH

At this point perhaps the money ran out for more national acts, and the club reverted to local bands, which it became known for.

August 31, 1962; The Diablos

September 1, 1962: The Dorados

September 2, 1962: Tommy Francis

September 3 – 9, 1962: The Sonny Williams Quartet

September 12 – 16, 1962: The Fendermen

October 4 – 7, 1962: The Blazers: “Hottest Band This Side of Hades”

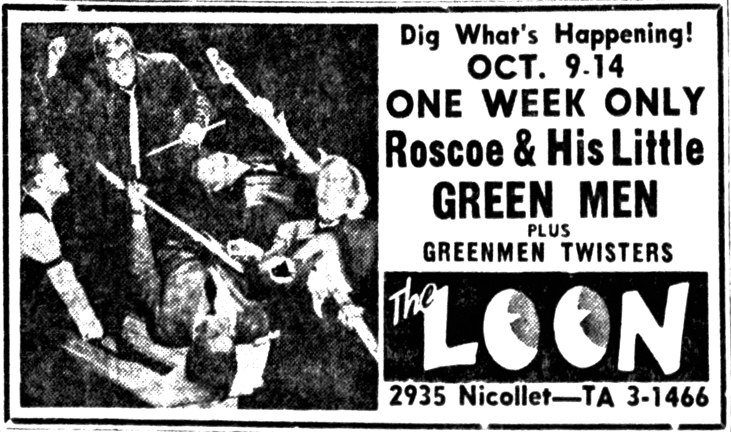

October 9 – 14, 1962: Roscoe and His Little Green Men. You can’t tell it here, but these guys sported green hair.

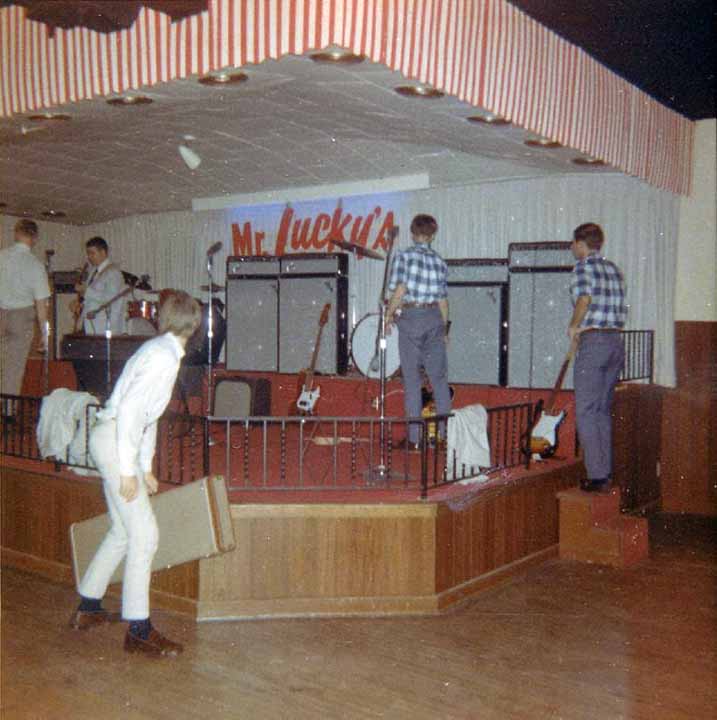

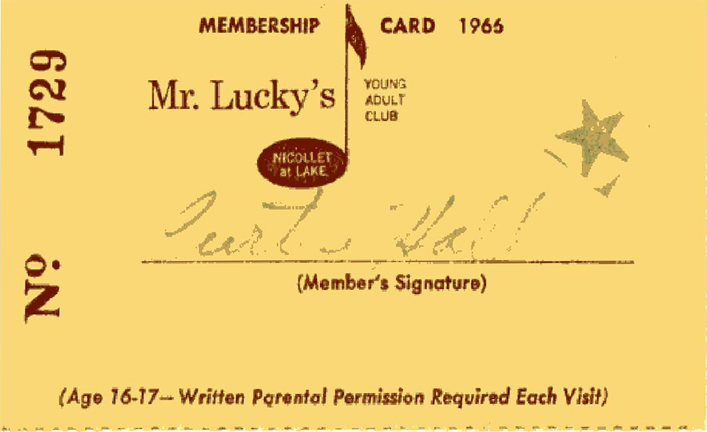

MR. LUCKY’S

1962

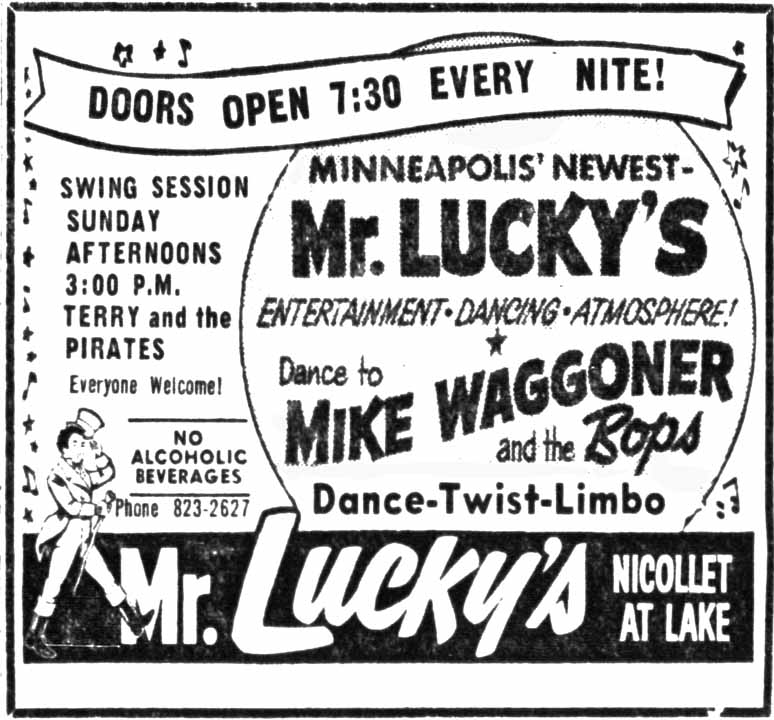

Mr. Lucky’s opened in December 1962 as the only local night club devoted exclusively to teenagers. Mr. Lucky himself was apparently a guy with a top hat, tails, a cane, and some nifty boots.

One of – if not the – first bands to play at Mr. Lucky’s was Mike Waggoner and the Bops. Terry and the Pirates played on Sundays.

1963

Mr. Lucky’s did not seem to get off to a good start. The only items I found were disturbing:

In February 1963, a 20-year-old young man with a St. Louis Park address went to the police station to protest the arrest of a friend for disturbing the peace at Mr. Lucky’s. He fought with the police in the car and at the station, breaking a glass pane in a door. He was admitted to General Hospital after he fell on the floor in the Court House, thrashed around wildly, and finally collapsed. Turned out he had taken 9 or 10 barbiturates.

Then in November 1963, a 19-year-old former Upper Midwest Golden Gloves boxing champion was found guilty of beating up a 17-year-old and knocking out four of his teeth. The cause? The victim danced with a girl friend of the assailant.

Mike Waggoner and the Bops played frequently at Mr. Lucky’s in 1963.

The Trashmen played Mr. Lucky’s on March 23, 1963. This was when the T-Men were still a popular local surf band; “Surfin’ Bird” would be released on November 13, 1963. (Thanks, minniepaulmusic.com!)

May 31, 1963: The Accents

1964

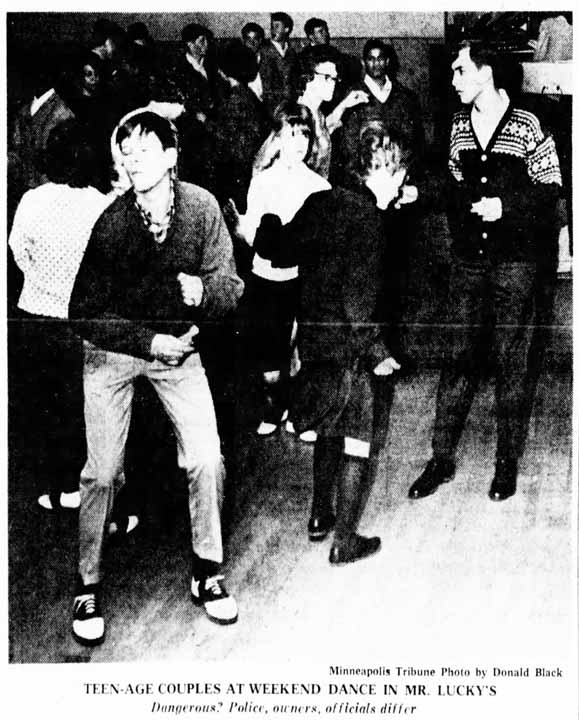

Mr. Lucky’s dodged a bullet in 1964 when there was pressure not to renew its license. The problem apparently started in the early hours of February 9, when 11 police cars called in to quell a disturbance. Over 200 kids were milling around after midnight as two cops were tagging a car with a noisy muffler.

The motorist’s companion “got a little mouthy,” according to police, and because of so many persons on the sidewalk, help was called for. “Mr. Lucky’s has become an attractive nuisance as far as we’re concerned,” [Ray Williamson, head of the Minneapolis Police Crime Prevention Bureau] said. “Some of my officers are outrightly indignant about the environment there. There is no question that there’s drinking going on in the place. The kids bring in their own bottles and spike the soft drinks.”

The club was owned by Rostar, Inc., and John R. Stephens was a co-owner. Stephens insisted that they were doing the community a service by keeping kids off the streets. The club was managed by Brian K. Lawson, a student at the U of M.

The timing was bad, since the club’s license was due for renewal on April 1. Other accusations against the club included:

- Cramming 1,200 bodies into a room rated for 500 (one article said a typical weekend night count was 700)

- Kids popping pep pills or “goof balls”

- Harboring known narcotics users

- Patrons fighting

Russell Green, police licenses inspector, complained that Mr. Lucky’s was requiring too much enforcement work by regular policemen, citing 32 police calls from November 1963 to February 1964. Most involved drunkenness, breach of the peace, or exchange of those pep pills.

One particular incident cited by police was vandalism of a “nearby beauty salon, which suffered $500 damage to the interior one dance night in December when vandals broke in and threw bottles of hair rinse and shampoo on the ceiling and walls.”

Stephens said that the club was supervised by three off-duty policemen, a half dozen waiters from the U of M, check room operators, and a manager.

Minneapolis Mayor Arthur Naftalin reported that he and his wife paid a visit to the club on a recent Saturday night and found nothing improper, but that “one visit was no basis for an over-all evaluation.”

“Asked what he thought would happen if Mr. Lucky’s were closed, a 17-year-old commented: “It’s just going to cause more trouble, because where are the kids going to go?”

Up against a council timing problem, Mr. Lucky’s had to close between April 1 and 10, 1964, when their license was finally renewed.

- Voting for renewal, Alderman John Johnson said “I’d rather see them in a dance hall in the city of Minneapolis than in a roadhouse 20 or 30 miles out.”

- Alderman Mrs. Elsa Johnson also voted for renewal, saying “The people in the area are very happy to have a fine place where their children dance in a wholesome atmosphere.”

- Alderman Robert MacGregor was reluctant, but said, “If it’s true, as they say, that there are no other places for teenagers to go on Friday and Saturday nights, then I think this is an indictment against our community.”

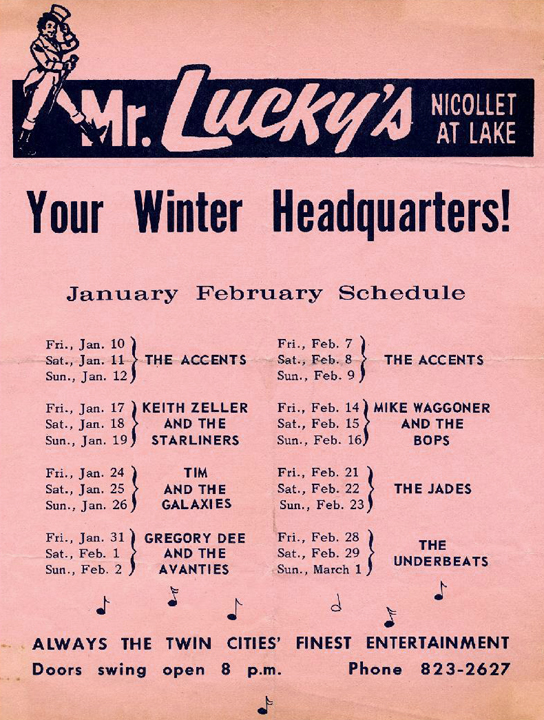

1964 Entertainment:

1964 started out with a full lineup of bands that we think of today as the golden era of local Twin Cities dance bands of the mid-sixties:

January 10-12, 1964: The Accents

January 17-19, 1964: Keith Zeller and the Starliners

January 24-26, 1964: Tim and the Galaxies

January 31 – February 2, 1964: Gregory Dee and the Avanties

February 7 – 9, 1964: The Accents

February 14 – 16, 1964: Mike Waggoner and the Bops

February 21 – 23, 1964: The Jades

February 28 – March 1, 1964: The Underbeats

Rod Eaton of the Underbeats had this to say about Mr. Lucky’s:

Mr. Lucky’s was one of my favorite places to play. The Underbeats and T. C. Atlantic played there frequently – including at least one New Year’s Eve gig each. The place dubbed itself “the Twin Cities’ first teen night club.” Fridays and Saturdays they routinely packed in about double the Fire Marshall’s occupancy limit. Unfortunately Mr. Lucky’s wasn’t so when it came to bad press. Fights were common – two rival clubs laid claim to the place. Uniformed cops watched the door and prowled the floor. In those pre-dope days, kids made do with traditional soft drink spiking. So all in all Mr. Lucky’s was a fun and exciting place to gather, dance, cruise, and play. Every night was an adventure. Those great 60s teen dance places vanished years ago. I feel sorry for today’s teenagers. They don’t get to hang out and listen and dance to real bands. DJ hosted parent/teacher chaperoned school hops just don’t provide the same experience.

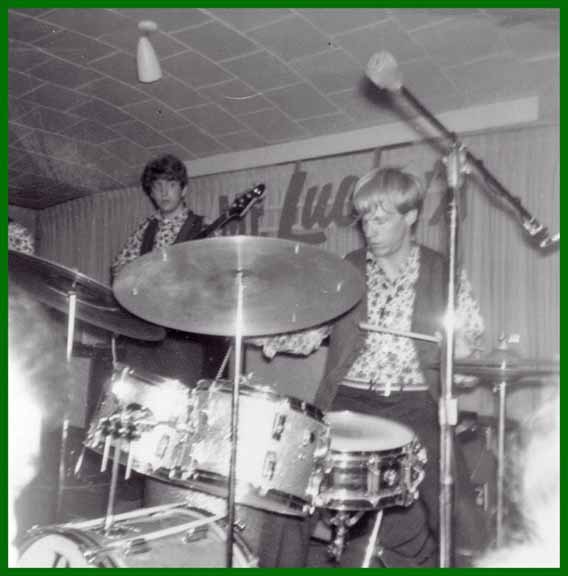

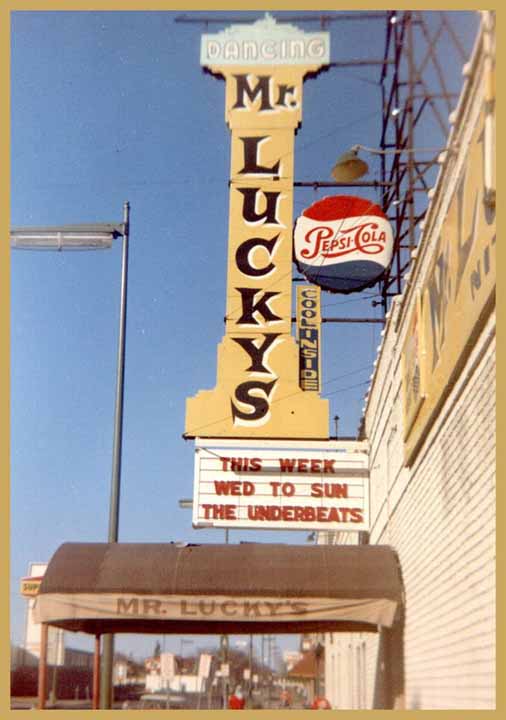

Rod Eaton also furnished this fabulous photo of the sign – obviously the Friendship Club sign covered up.

August 28, 1964: Battle of the Bands – The Chancellors vs. The Renegades

August 29, 1964: The Chancellors

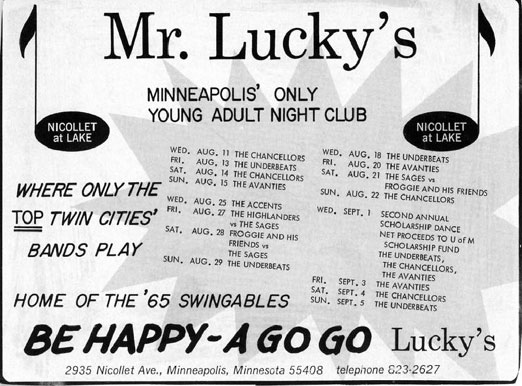

On August 30, 1964, Mr. Lucky’s sponsored its first annual scholarship dance. Proceeds provided scholarships to two freshmen at the U of M. Recipients were selected by the University Scholarship Committee. Entertainment was provided by local bands the Underbeats, the Accents, and the Chancellors.

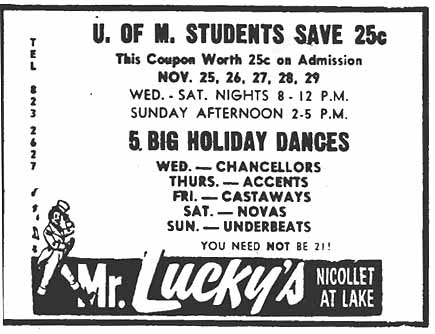

Thanksgiving break brought the best of the local bands to Mr. Lucky’s:

November 25, 1964: The Chancellors

November 26, 1964: The Accents

November 27, 1964: The Castaways

November 28, 1964: The Novas

November 29, 1964: The Underbeats

1965

In 1965 Mr. Lucky’s was expanded, and was open on Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday nights and Sunday afternoons. That year the owner was identified as Bob Roosen and the manager was Bryan Lawson.

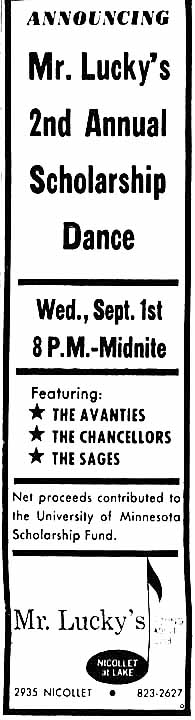

September 1, 1965: Mr. Lucky’s Second annual scholarship dance featured Gregory Dee and the Avanties, the Chancellors, and the Sages.

1966

Mr. Lucky’s Third Annual Scholarship Dance was held on August 28, 1966. Bands included Michael’s Mystics and Stillroven. Proceeds were used to set up two full-year scholarships for freshmen at the U of M.

December 17, 1966: City Strangers

MAGOO’S

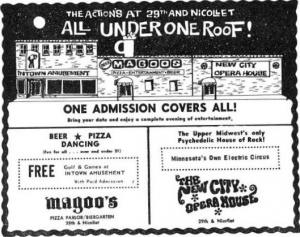

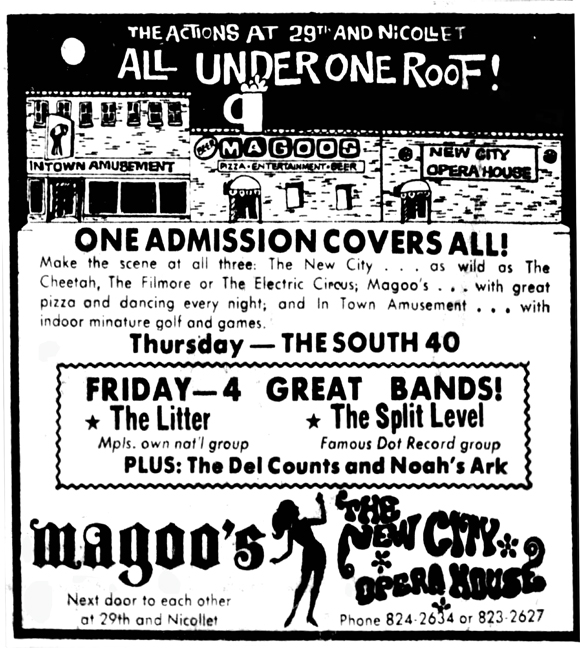

The story of Magoo’s is told following the section on the New City Opera House – the tale isn’t exactly linear. The space started out as a Post Office, and became Magoo’s in 1965. Concerts between the end of 1967 and the end of 1970 were identified as taking place at Magoo’s, the New City Opera House, or sometimes Magoo’s New City Opera House. Apparently the bands alternated. I have listed all those concerts below under Magoo’s/NCOH, since it’s hard to tell (unless there’s a photo) who played at which stage. They were good concerts with a great mix of national and local acts. I’m sure there were more than listed.

NEW CITY OPERA HOUSE

Mr. Lucky’s was renamed the New City Opera House by ace guitarist Zippy Caplan, who was working there between gigs, in about 1967. Zippy says the name just came to him – there was no contest as previously reported. At that time the manager was Gary Jorgensen.

1967

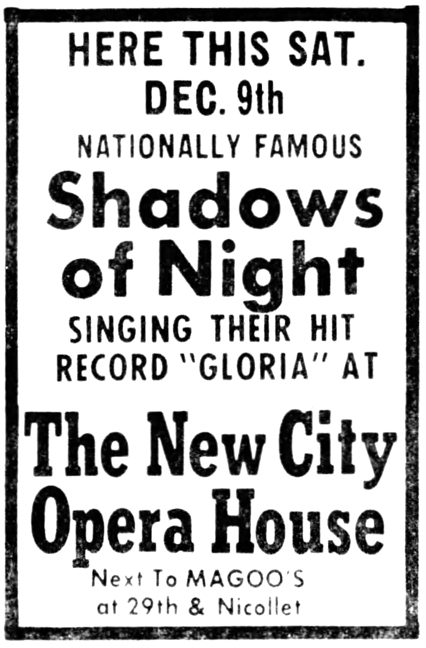

December 9, 1967: Shadows of Knight, NCOH. With the Electras.

December 30, 1967: The Litter, T.C. Atlantic, C.A. Quintet, Happy Dayz, and the Grasshoppers.

December 31, 1967: The Litter, Grasshoppers, Nickel Revolution, Love Express, Xpressmen

1968

In 1968 New City was advertised as “The Upper Midwest’s only Psychedelic House of Rock!” and “Minnesota’s Own Electric Circus.”

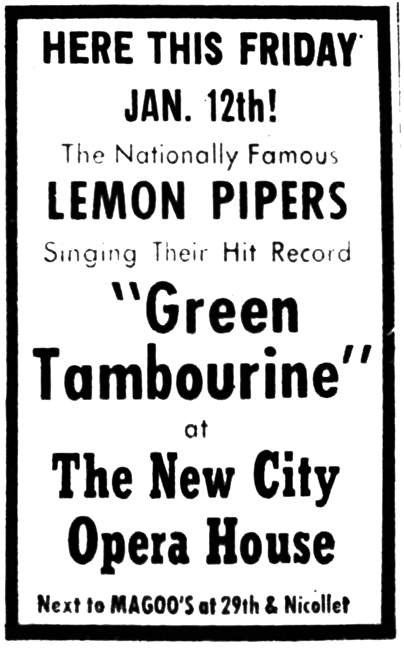

January 12, 1968: Lemon Pipers, NCOH

February 29, 1968: South 40, a successor to the Castaways

March 1, 1968: The Litter, Split Level, the Del Counts, Noah’s Ark

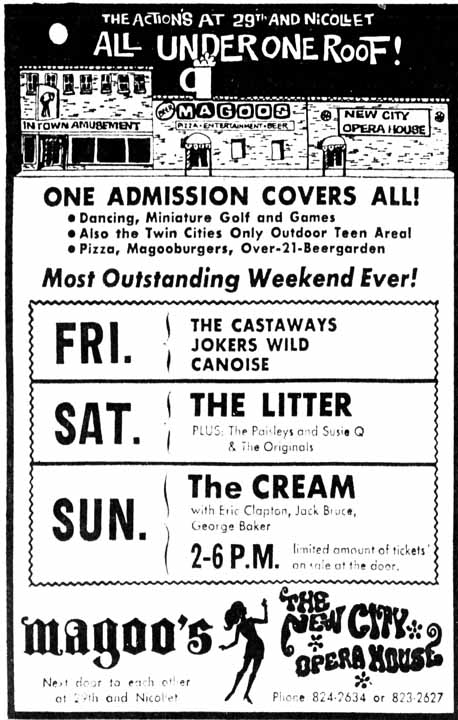

May 3, 1968: The Castaways, Jokers Wild, Canoise

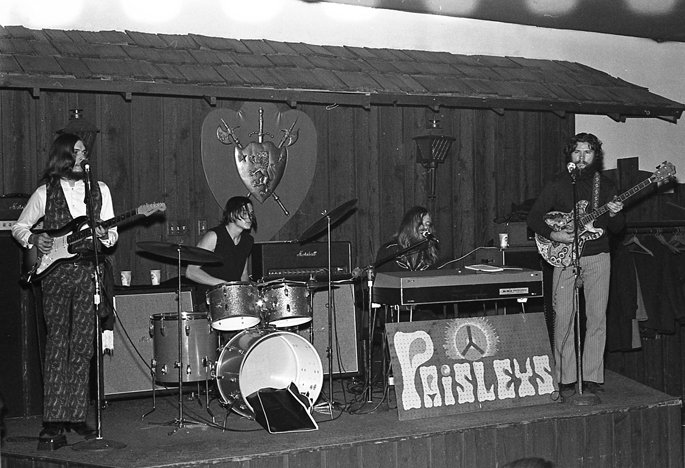

May 4, 1968: The Litter, The Paisleys, Susie Q and the Originals

CREAM, NCOH

On May 5, 1968, Cream underwhelmed the audience at the New City Opera House, and vice versa. Read the story here.

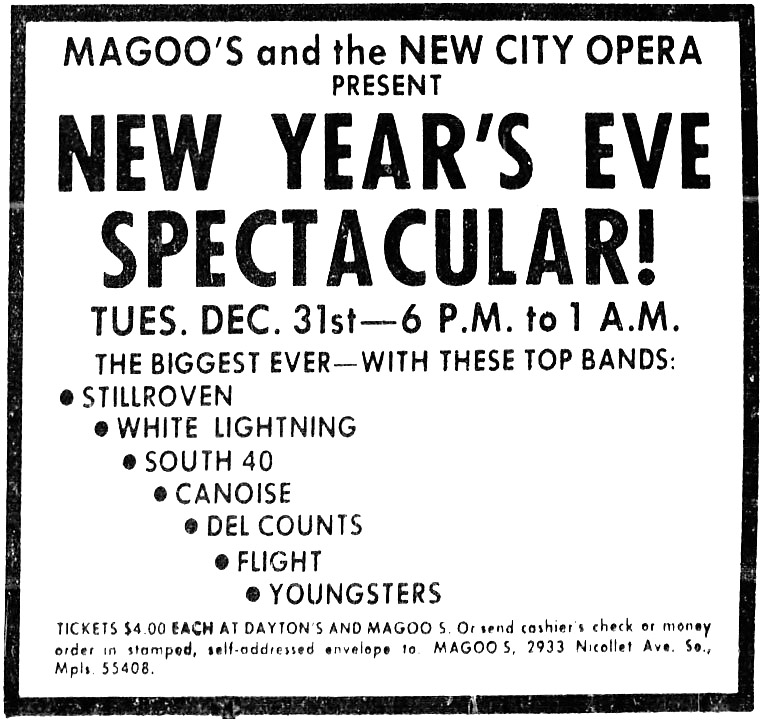

New Year’s Eve 1968:

- Stillroven

- White Lightning

- South 40

- Canoise

- Del Counts

- Flight – soon to become Pepper Fog

- Youngsters

Zarathustra was one of the bands at Magoo’s New Year’s Eve party.

1969

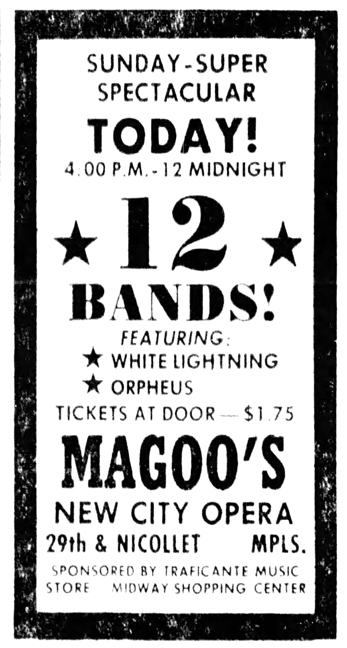

February 9, 1969: 12 bands, including White Lightning and Orpheus

February 14 – 15, 1969: Friend and Lover (probably NCOH)

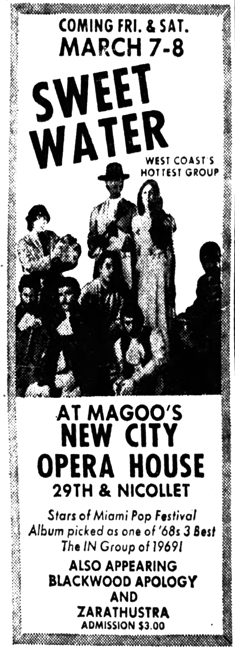

March 7-8, 1969: Sweetwater, NCOH. Also local acts Blackwood Apology and Zarathustra.

September 28, 1969: C.A. Quintet

SANTANA, NCOH

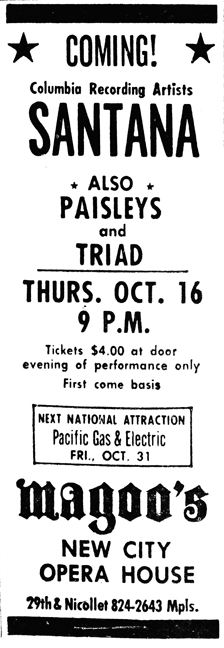

October 16, 1969: Santana, opened by the Paisleys and Triad. In a review of a return appearance several years later, Marshall Fine remarked that there were 500 people in the audience and the “fledgling band pounded out some of the fiercest, rawest Latino rock I had heard.” (Another report was that there were only 75 people there.) Fine noted that the 1973 performance at the Met Sports Center was much different, with smoothed out edges and added depth reflecting Carlos Santana’s spiritual journey.

PACIFIC GAS & ELECTRIC, NCOH

October 31, 1969, with the Grasshoppers and Pride and Joy.

Marshall Fine’s review was fierce:

To discuss Pacific Gas and Electric is to discuss adequacy. Talking about them is talking about being average. Describing them is describing mediocrity. Listening to them is unequaled boredom.

For PG&E are, without a doubt, the most average, most adequate, most mediocre and therefore most boring group around.

Friday night at the New City Opera House, they tried to play what they consider to be very heavy blues. But it is just a rehash of everything Muddy Waters and B.B. King and John Lee Hooker ever did.

They do not have the power of a blues band like Paul Butterfield’s or the uniqueness of a Johnny Winter. They play just plain middle class ordinary electric blues, with the right sprinkling of “oh babys” and “oh mamas” to pass.

The whole problem is they got away with it. They had the crowd screaming and whistling and shouting for more.

But, after all, there is no accounting for tastes.

NEW COLONY SIX, NCOH

November 29, 1969, opened by Lemon Pepper

BLUE CHEER, NCOH

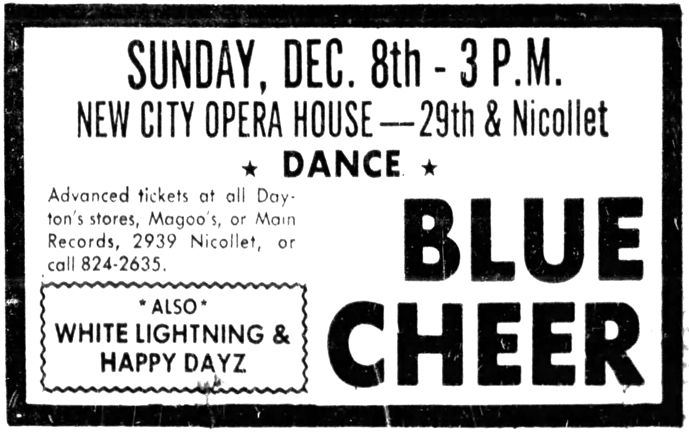

December 8, 1969, opened by White Lightning and Happy Dayz.

ZEPHYR, Magoo’s

December 12 – 13, 1969: Zephyr’s performance was reviewed in the January 16, 1970, edition of the Minneapolis Flag:

Magoo’s audience loved them. I loved them. My old lady loved them. And the ZEPHYR loved them. “Man,” Candy [Gibbons] told me in an interview after the show, “before we came up here we’d heard reports… bad reports…about Minneapolis. We were told we wouldn’t dig it. Our promoters said, ‘Be glad that Minneapolis is your first gig because you won’t like it.’ … But they were wrong. All wrong.” Put that in your hookah and smoke it. ZEPHYR felt the Midwest to be turned on more than they had figured. Nothing but life, love, sex , and energy emerged from this group of fine musicians. They’re definitely not the death rattle of underground music (as they have been called at times). On the contrary, man,… they’re going through some positive and fruitful changes.

1970

COLD BLOOD

January 30 – 31, 1970: Cold Blood was a group from San Fransisco featuring vocalist Lydia Pense.

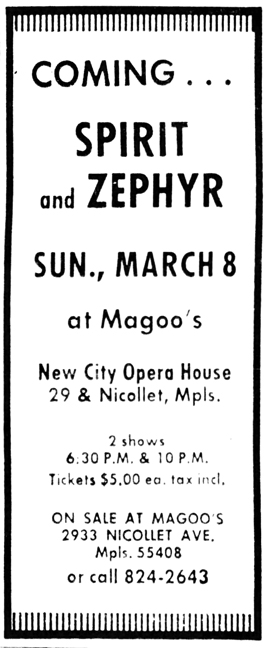

SPIRIT AND ZEPHYR

March 8, 1970. Nova Lights and a new stage.

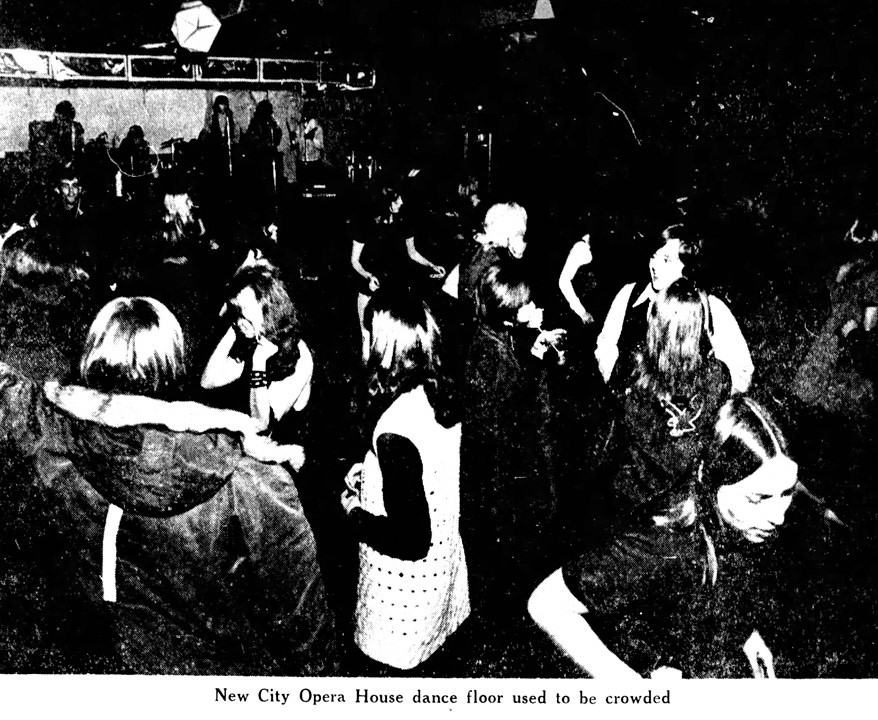

November 14, 1970: An article in the Star noted the lack of business at all of the teen dance halls in the ‘Cities, attributed to the rise of festivals and concerts. At Magoo’s/New City Opera House, only 100 kids were dancing in a space that could hold 1,500. Manager Gary Jorgenson said that if business doesn’t pick up, the hall would close. In January 1971 the Insider reported that owner Bob Roosen turned the NCOH over to the Mystics to run, but that didn’t work out either.

Apparently Bobby Jackson, who rented the Magoo’s side (see below) from November 1970 to April 1971, also ran the NCOH. Both got trashed in the April 1971 riot.

2933 NICOLLET: MAGOO’S

POST OFFICE

In April 1952 a portion of the Friendship Club was altered to create the Lake-Nicollet branch of the Post Office, transferred from 117 West Lake Street. The 9,500 sq. ft. section of the building, with a 58 ft. frontage, was leased for ten years from Mrs. Kathryn Brecheisen, the owner of the Friendship Club. The Post Office had 79 employees, including 68 carriers. The Superintendent was Charles Becker.

In December 1963 it was announced that the space was “inadequate” and a new location was required.

MAGOO’S

1965

Magoo’s pizza parlor replaced the Post Office in April 1965. It was next to Mr. Lucky’s and was under the same management: owner Bob Roosen and manager Brian Lawson.

A long ad announcing its opening was published in the Strib on April 22, inviting people to “Enjoy an Irishman’s Italian Pizza in a Bavarian decor while you listen to cool live jazz in a family atmosphere.” It boasted that it was the world’s largest pizza parlor, seating 432 people and serving 28 kinds of Beek’s pizza. “There’s a giant open hearth fireplace, wooden chairs and tables, a bandstand which everyone can see, and an amusement lounge up front.” Will Jones wrote that the waiters wore lederhosen. He also reported that there was no liquor or beer, but it probably served beer from the outset.

Starting on April 2 – 3, KQRS program director Herb Schoenbohm’s Jazz Trio provided the music on Friday and Saturday nights. By September the Mike Elliott Trio, originally from Denver, played on Thursday and Sunday nights. Will Jones expressed his gratitude for this difference from Shakey’s banjo music. He noted that “between musical numbers, and sometimes during them, the ticket-numbers of pizza orders were boomed over the microphone. An indefatigably polite and pleasant crew of young men kept the system functioning smoothly.”

Owners were so optimistic about the success of Magoo’s that they were planning a second Twin Cities location, and were planning to sell franchises.

An ad from July 1, 1965, had reduced the number of types of pizza from 28 to 14 – perhaps they had dispensed with the tuna variety. Yech! That ad also did not mention beer.

In September, Will Jones compared Magoo’s to Shakey’s Pizza:

The same long, low benches for tables; the same short, sturdy stools; the same kind of serve-yourself setup for ordering pizza and light and dark German-style beer; roughly the same noise level; and the same sort of camaraderie that results from such calculated jammed-togetherness, especially on weekend nights.

In the October 1965 issue of Twin City a-Go-Go, local comedian Danny Klayman likened Magoo’s to an Italian resort with beautiful decor. Tuesdays featured turtle races (bring your own or rent one), and on Monday through Wednesdays they showed “Magoovies” – Three Stooges, Laurel and Hardy, etc.

A large ad in November mentioned the Biergarten and live jazz, but still encouraged people to bring the family. A noon buffet had also been added.

1966

In 1966 the music at Magoo’s changed from jazz to what looks like Dixieland and “singalong” music. The stress was still on a family pizza parlor.

MAGOO’S SURRENDERS TO ROCK ‘N’ ROLL

On August 5, an ad substitutes Rock & Roll for Sing-a-Long, signalling the turning point for Magoo’s.

1967

In 1967 Magoo’s was managed by Gary Jorgensen, who announced that June that the dance floor had been expanded. Owner Bob Roosen had three windows installed in the north wall.

MAGOO’S AND THE NCOH

Concerts between the end of 1967 and the end of 1970 were identified as taking place at Magoo’s, the New City Opera House, or sometimes Magoo’s New City Opera House. Apparently the bands alternated. I have listed all those concerts up above under Magoo’s/NCOH. They were good concerts with a great mix of national and local acts. I’m sure there were more than listed.

The Magoo’s story continues below, in November 1970, when it was leased to the Cafe Extraordinaire.

MAGOO’S AND SONS

Magoo’s closed in May 1970; Will Jones reported that it had gone through a number of changes, suffered a shortage of business, and the owner decided to concentrate on the New City Opera House, “the rock dancehall that continues to bang away next door under the same management.”

Magoo’s refused to die, though, and had another life as Magoo’s and Sons. In June, four friends who had worked there made a deal with owner Roosen to operate it at their own expense and give Roosen a percentage of the receipts. The new proprietors were:

- Keith Smile, 19, a U of M student and head pizza cook

- Randy Larsen, 16, student at Central High and – despite his age – described as having worked there for several years.

- Paul Young, 20, U of M student

- Tim Eaton, 21, the only one old enough to serve beer

The guys decided to turn the place into a venue for folk, blues, and jazz. They got rid of the strobe lights and replaced the big tables “that made it kind of like a barn” and made smaller tables themselves.

Performers included:

June 25, 1970: Lonnie Knight and Shannon Elliot. The venue was listed as Magoo’s and Sons Folk and Blues Club. This may be the show where Lonnie sang his song, “Banging One’s Head on the Moon.”

Poor Howard

The Argirs, a folk-and-blues group featuring “a talented young blonde on flute.”

August 21, 1970: Jerry Rau; venue listed as Magoo’s and Sons Blues, Folk and Jazz Club.

September 3, 1970: Open stage

Things were a little dicey in terms of audience: “One night Lonnie Knight worked for a $10 bill and a sandwich.” Moms brought in pies to sell, and they tried to create a coffeehouse type atmosphere, although they avoided the word. They couldn’t afford to restore the pizza offerings, but were optimistic. Unfortunately, the guys lost their entire $200 investment, but they gave it the old college/high school try.

CAFE EXTRA-ORDINAIRE

The Cafe Extra-Ordinaire, owned by Bobby and Doris Jackson, was a jazz club, originally located across the street at 2954 Nicollet Ave. It’s unclear when it first opened; one source would compute to January 1968, while another would indicate about January 1967. The first ad found is from January 1969.

An article in the December 1969 – January 1970 issue of Metanoia magazine reveals that Jackson was himself an accomplished jazz drummer. A house band included musicians such as Bobby Lyle, Morris Wilson, and Jim Bell.

The purpose of the club was posted on a sign on the door: “To create more respect for the jazz musician and to create an atmosphere favorable to increased public acceptance of true jazz as a great American art form.”

In January 1970, critic Allan Holbert described the original venue:

Inside the Cafe Extra-Ordinaire has an atmosphere not unlike those jazz clubs that thrived in New York’s Greenwich Village during the 1950s. The bizarre modernistic paintings on the walls and the geometric forms on the ceiling take on an eerie glow from the black fluorescent light.

The musicians perform in front of a floor-to-ceiling curtain of aluminum foil that reflects the changing colors of lights that are thrown on it during the hour-long sets.

The chairs are arranged in rows, auditorium style, and sprinkled among them are small tables to hold such coffees as “Cafe Capuccino Mocha” and “Cafe Ravel” or such exotic drinks as “One Step Beyond” and “A Crippled Wing,” which are prepared and served by Jackson’s wife, Doris … [The club did not have a beer or liquor license.]

Except for an occasional “Tell ’em Bobby,” or “Go baby,” the audience of 60 or so jazz buffs was quiet and attentive.

“I know we’re not going to get rich here. I just hope we can keep the place open. What we want to do is help people understand progressive jazz and provide some work for musicians. We got some great jazz musicians in this town. You know what they’re doing? They’re playing in the strip joints down on the avenue. They gotta eat.”

In February 1970, Star critic Peter Altman noted:

The un-selfconsciously interracial audience evinced a very different kind of informality than one sees at the Labor Temple’s rock concerts. Attire was truly come-as-you-are. There was no show, no irritability, no antagonism in the air, just as there was no need for police. All the vibrations were good, the atmosphere was cool.

The night he was there, the audience only numbered about 50, “yet the room was alive and seemed populated with good will.”

Shows at 2954 Nicollet included:

1969

January 7 – 31, 1969: Afro Jazz Quintet

February 14 – 21, 1969: Gene Hubbard Quartet

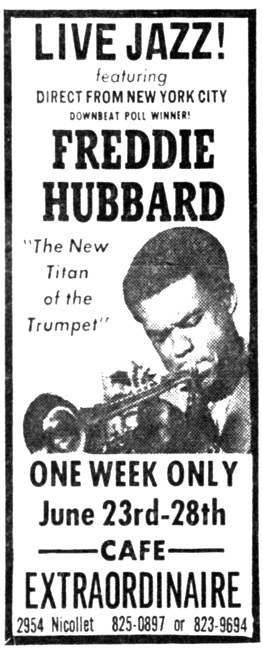

June 23 – 29, 1969: Freddie Hubbard

December 1969: Paul Arko Trio

1970

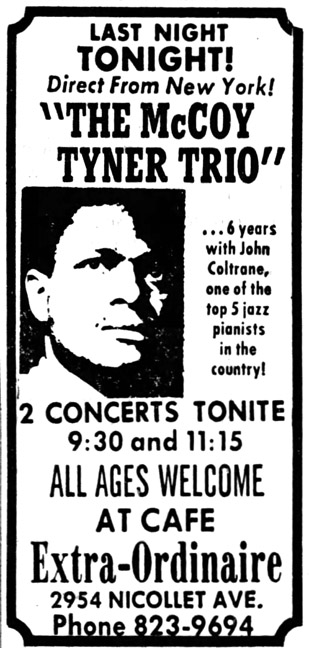

January 13 – 18, 1970: McCoy Tyner Trio

February 6 – 15, 1970: Sam Bevins Quartet

February 27, 1970: Pharoah Sanders Quartet

March 1970: Beau Baily Sextet

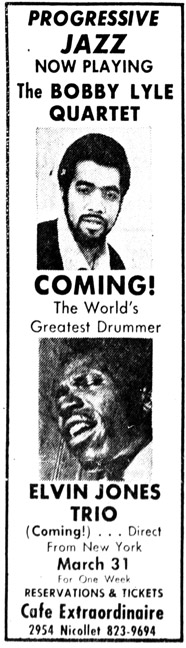

March 13 – 15, 1970: Bobby Lyle Quartet

March 31 – April 5, 1970: Elvin Jones Trio, with Joe Farrell on tenor sax and Wilbur Little on bass. Jones was billed as “the world’s greatest drummer.” The show got an excellent review in the Insider: “Here’s hoping Bob Jackson’s policy of importing national jazz groups will be continued; he does it for the music. His cafe is too small to make money.”

May 19 – 24, 1970: Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Star critic Peter Altman was blown away by the performance of Kirk, who played half a dozen wind instruments. Backing him up were Ron Burton on piano, Jimmy Madison on drums, Vernon Martin on bass, and Texidor on “soundtree (bells, rattles, and percussion devices”).

Kirk is a phenomenon who defies classification. He is a prodigy of energy, a marvel of invention, a master manipulator of moods, and a technical whirlwind. The average person would call his musical style modern jazz; Kirk prefers black classical music. Both terms are helpful, but neither hints at the circus virtuosity of Kirk’s performances … [The performance] stirred emotions up, ever ground them down; ignited, didn’t steamroll; made the audience yell and move, not sit subdued.

June 8 – 13, 1970: Mickey McLain Trio

September 14 – 19, 1970: Sid Farra Trio

Jazz Festival:

September 29 – October 4, 1970: Elvin Jones Quintet

October 13 – 18, 1970: Joe Henderson Quintet, with Henderson on tenor sax, Woody Shaw on trumpet, Lenny White on drums, Ron McClure on bass, and George Cables on electric piano. Star critic Peter Altman noted that the electric piano “at times sounds like a celesta, at other moments suggests a vibraharp … and adds a bright quality to a predominantly heavy sound.” Altman concluded his review with: “Much of the band’s appeal is attributable to the evident joy its members have in playing together. After taking a while to limber up, the quintet really got to swinging, rocking and wailing in the late hours.”

October 20 – 25, 1970: Eddie Harris Quartet

November 1 to 5, 1970: Kenny Burrell (not on the ad)

2933 Nicollet

In November 1970 the Cafe Extra-Ordinaire moved from their tiny club, where they had had some success presenting live jazz, to the much bigger Magoo’s building. Jackson leased the building with an option to buy. It was a big change; capacity grew from 101 to 800, and the lease came with a 3.2 beer license. The jazz shows continued; the house band was the Hubert Eaves Quartet.

Peter Altman described the new digs:

The room is long and rectangular, and the bandstand is set up along one of the long sides, which might mean that if a crowd ever filled the place it would be hard to see well from the most distant tables. But sound carries well and there are surely more good, close seats now than there were before the relocation.

November 17 – 22, 1970: McCoy Tyner Quartet

December 8 – 12, 1970: Freddie Hubbard Quintet. Backing trumpet player Hubbard were Junior Cook on tenor and soprano saxophone, Louis Hayes on drums, Joe Bonner at the piano, and Mickey Bass on bass. Peter Altman reported a small audience on opening night.

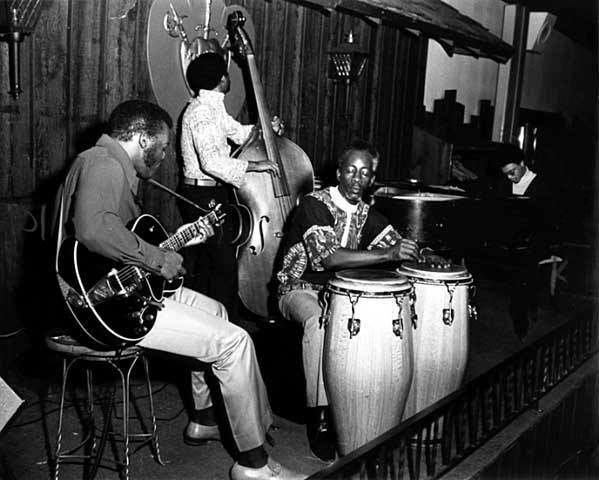

December 15 – 20, 1970: Hubert Eaves Quintet. Photo below (with Magoo’s shield still on the wall) features Hubert Eaves, Joe Hill, Jerry Hubbard and Felix James.

1971

January 5 – 10, 1971: Maurice MacInnis

January 20 – 24, 1971: Organist Richard “Grove” Holmes

January 26 – 31, 1971: Pianist McCoy Tyner

February 2, 16: Lamont Cranston Blues Quartet

THE FAUX BUDDY MILES FIASCO

The Jacksons booked Buddy Miles to appear on April 10, 1971. An article promised sidemen Andrew Lewis on clarinet and organ, Marlo Henderson on guitar, Charlie Karp on lead guitar, Dave Hull on bass, Tom Hall on trumpet, Hank Redd on tenor sax, Mike Fugate on trumpet, and Stemsy Hunter on sax.

But things went awry. Tom Behr shared the story on Facebook:

[My] brother Bob was an agent and the club owner asked him to book Buddy Miles. When Miles’ agent said he’d need a deposit to lock the date in, the club owner told Bob that he would take over the negotiations and send in the deposit. Then Bob was told that Buddy would be coming without the Express Band, so Jr. Trejo’s Saxon Soul was asked to sit in as Buddy’s back up band.

Here’s where the story gets better: Jr. said they had a rehearsal the afternoon of the show and Buddy played drums, but asked Jr.’s singer to sing his songs because he had laryngitis.

The crowd was beginning to sense there was scam going on. [Apparently someone recognized the keyboard player’s B3, which was covered with a blanket, and that’s when people realized something was up.] On the first break Jr. told the club owner that he finally figured out this guy was a sham and they were going to pull the plug on the show. [Jackson] said, “You better play or the crowd will trash the club not to mention your equipment!” Then he says “Hey Jr. can you play something by Chicago?” (I’m serious)

So as soon as they start to play the second set, people where booing, and throwing food, then drinks at the band, one by one the guys get off the stage, leaving “Buddy” to play a drum solo. Now as the riot is on, fake Buddy jumps off the drums, tosses off his Afro wig and out the back door he ran. The epilogue gets better: the Trib had a picture on the front page of the wig sitting on a table with a bunch of beer mugs, and it turned out the fake Buddy Miles was the janitor at Sacred Heart Church on the East side. I’m still laughing at that one!!

Marshall Fine was suspicious; in his review of April 12 he noted that:

- “Miles” was obviously wearing an Afro wig.

- Miles was fatter than “Miles.”

- Miles has a huge ego, but “Miles” stayed in the background in a dark stage.

- “Miles” only sang backup, while at a previous Labor Temple show, Miles “dominated his group with his thin voice, heavy-handed mannerisms and tiresome drumming.”

- “Miles” “did a drum solo at the end that was superior to anything Buddy Miles has done.”

From the Minneapolis Tribune, April 12, 1970 (Terry Farrell):

Youths rip club during disturbance

About 1,000 young people went to the New Cafe Extraordinaire late Saturday to hear black drummer-singer Buddy Miles and got “ripped off,” youthese for “taken.”

So, some of them decided to rip off the Cafe Extraordinaire, 2933 Nicollet Av. And they did.

They smashed the plush music club’s interior stained-glass windows, overturned and smashed tables, damaged some of the band’s equipment, emptied a fire extinguisher on a rug, tore open cash registers and a cigarette machine, broke a plate glass window, hurled glass mugs about the room, and then pushed out onto Nicollet Av.

Police were called about midnight, shortly after the eruption began. Squad cars quickly blocked off that portion of Nicollet. Policemen began to disperse the crowds and about an hour after the disturbance began it was all over.

It began when the predominantly black crowd realized that the performer who claimed to be Miles was an impersonator. And each of them had paid $5 a ticket.

Club owner Bobby Jackson, sitting amidst the ruins of the club, Sunday said he is not “at liberty to say what went on” concerning the impersonation. But, he added, “all responsibility should lie with the real Buddy Miles. A contract was signed with him.”

Jackson, in good spirits despite the loss of a night’s sleep and what he estimated to be $50,000 in damage to his two clubs (the New City Opera House adjoins the Extraordinaire) said “somebody slipped along the line.”

He said he did not think that his insurance would cover the damage to the clubs, valued at $1450,000. “There’s no way we can reopen.”

Jackson, 29 and black, said he “would go back to playing drums for $100 a week.”

He said that when the incident began he “split – there was no reason to stay.” He said he grabbed money from two cash registers and went home.

Soon after Jackson left, the police arrived. For the most part, though at times, gruff, they were restrained and efficient in dispersing the crowds. However, at least one incident did occur.

About six policemen led by an officer and with a police dog, crossed from in front of the clubs to the west side of Nicollet Av.

The officer, billy club extended, shouted to the people who lined the sidewalk to “move it. Go on, get out of here. One black man did not move fast enough. The officer kicked him in the groin, and he was picked up off the sidewalk by two other policemen to a squad car. Another man was also arrested.

No injuries were reported by police. The two men were arrested on charges of breach of the peace, failure to obey an officer and obscenity in public, police said.

Marshall Fine shed more light on the situation on April 15, revealing that the back-up band was called Saxon, led by Gary Winkler. The band had been hired to back Miles, and worked hard to learn the material. They met “Miles” just before the show, and noticed that “He was too skinny, and his hair looked fake.” Then Winkler was told that Miles had laryngitis, and that he’d have to sing all his numbers. Winker reported that when he realized the hoax, “I was embarrassed, man, like really ashamed. It got to the point where I was signing with my back to audience, I was so ashamed.”

It was after the second set started that the crowd turned. “Miles” hit the back door, and owner Jackson hit another door with $7,500 to $10,000 of the ticket money. Neither “Miles” nor Saxon got all the money they were promised. KUXL disc jockey Jimmy Smith, who had emcee’d the show, told Fine that he looked for Jackson, but his apartment had been cleared out and his phone cut off. This turned out not to be true; a subsequent article says that he had come to the police station and given a statement. He told police that when the hoax was discovered he had started refunding money, but was overcome by the crowd and left.

Another article by the Tribune’s Howard Erickson gave this as Jackson’s account:

Although some patrons became upset at what they considered deception and demanded their money back, “most of the people were satisfied, I think.” He said refunds were being made at the box office when “two, maybe three guys started making a big scene. One of them threw a beer bottle through a stained-glass window, hollered ‘Phoney,’ and fired a pistol. That got the whole audience panicky. The band left the stage and everybody else headed for the exits, fast. That’s what produced the damage – most of it was accidental from the crowd’s haste.”

Apparently the real Miles had been in town, but when he didn’t get the front money he was promised, he cancelled and went back to Boston, where he was during the whole thing.

The event was reported in Rolling Stone on May 13, 1971, in an article rather harshly entitled “You’re Not Buddy Miles, You Pig.” The last paragraph reads:

The real Buddy was not available for real comment, but his company, Mercury, claimed that Miles’ manager cancelled out of the gig the day before because Jackson had come up with only $500 of the $1500 deposit required by the contract.

PERRY PEOPLES

Regardless of whether he also worked as a church janitor, the imposter was actually an accomplished local drummer. Perry Carson Peoples, Sr., 40, had been performing around town for decades – one note said he played for the Stan Haugesag Orchestra for many years. In 1958 he led his Interpreters of Jazz at St. Paul’s Red Feather. Members of the combo included Hensley Hill on flugelhorn, Woodson Bush on alto, Irv Williams on tenor, Tim O’Donnell at the piano, David Facen, bass, Ira Pettiford. The group also presented a concert in 1958 at Macalester College. In 1963 Peoples was in Irv William’s Quartet.

Peoples was born in Kansas in 1928, one of nine children. In 1940 the family was living at 706 Rondo Street in St. Paul, and his father was a singer, employed under a WPA project. Three of his sisters were maids. The family had apparently moved to Minnesota in about 1935.

Although an article on Peoples identified him as a professional musician for 25 years, it also quoted him as saying he was the chief engineer at a St. Paul “institution” which he did not identify. In 1972 he was working as the maintenance manager at Crystler City (6800 Wayzata Blvd. in Golden Valley, now the site of Menard’s). But he was back working in music in 1978-1980. References to Perry, Sr. end in 1989 with a letter to the editor indicating that he now lived in North Minneapolis. He died on January 16, 2003.

Both Marshall Fine and Terry Farrell reported that Peoples said that he did not know that he was impersonating Miles and that Jackson had hired him to play “on my own merits.”

END OF THE EXTRA-ORDINAIRE

The incident was investigated by police, and detectives had taken the matter to the county attorney’s office for review, but the it was found that “There wasn’t sufficient evidence for us to prove a felony by any particular individual.” Dayton’s refunded money to those who had bought their tickets there.

However, although no criminal charges were brought, the Minneapolis license inspector recommended that the City Council revoke Jackson’s beer license. And as it turned out, Jackson lost his liquor license for a bad check. Jackson had paid for his license renewal with a check for $650, which bounced. He came back and was able to pay $300 on acccount, and was told to pay the other $350 on April 12, but when he came back to pay the balance, he was refused. When he asked for the original $300 back, the treasurer’s office refused to give it to him. Alderman Robert Denny told him that he “was lucky to get out with that,” and that if the whole $650 had been good, he would have probably lost that “for other reasons,” meaning the riot. As Jackson left the committee room, he was heard to say, “They’re all a bunch of liars in there, man.”

CODA

One of the men arrested on the night of the riot was Oscar Thomas Govan. He was found guilty of making inflammatory statements when the police were clearing the area. Officers testified that he had shouted things like “Kill the pigs,” “Burn the squad cars,” and “Get bricks.” Tribune reporter Terry Farrell (see above) testified that Govan had been kicked in the groin by a police officer and knocked to the ground during the arrest, but the judge said that that was irrelevant. (Govan, a Marine who was wounded by a land mine in Vietnam, received 100 percent disability payments.) He received a suspended sentence of 30 days in the workhouse. Govan died in 1988 at the age of 40.

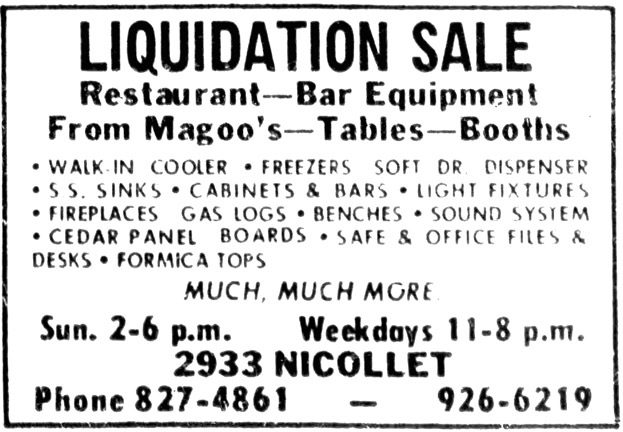

The riot was the end of the line and the music officially died. All fixtures of the building were sold in November 1971.

MAGOO’S TABLE TENNIS CLUB

An interesting postscript is that Magoo’s had apparently become a table tennis venue, and on December 12, 1971, the club moved to new quarters at 1516 E. Lake Street. The club featured 12 tables, balconies for spectators, and a pro shop.

RETAIL STORE

Starting in March 1972 the building was altered to be a retail store, according to permit records. No idea what that was.

DEMOLITION

The building that had hosted so much local music throughout the years was torn down in March 1977. There’s a rumor that the floor was used at a music or ballet school? The City of Minneapolis owns the property, which is leased to K-Mart. Nicollet Ave. was completely cut off in the process.