Cassius Bar and Cafe

Minneapolis

ANTHONY B. CASSIUS

To talk about the Cassius Bar is to talk about Anthony Brutus Cassius, so we’ll start with his impressive resume. Much of the information below comes from:

- A long article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune published on August 14, 1983, on the occasion of his passing

- An article dated December 8, 1939, in the Minneapolis Spokesman

- Census data from Ancestry.com

A warning that some of these dates don’t match up, which happens when they come from different sources and different memories.

A.B. Cassius was the son of southern slaves; his father was a minister who had run away from a plantation. Census data shows that his father was born in Virginia and his mother was born in Texas.

Anthony was born on June 29, 1907, in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

In 1920, Anthony left his family in Guthrie, Oklahoma at age 13, leaving behind 22 other brothers and sisters. He made his way to St. Paul with $7 in his pocket.

He found work at a hotel and slept on a mattress in its basement while he attended Mechanic Arts High School in St. Paul. He went on to attend Macalester College, where he was a star football player, and the University of Minnesota; he reported to the Census in 1940 that he completed one year of college. The Star Tribune reported that at the U of M, he decided to open a restaurant where blacks would be served on an equal footing with whites.

In 1930 he was a waiter in a hotel restaurant, presumably the Curtis, where he served his apprenticeship.

The Strib reported that in 1936 he left the Curtis to run a series of beer parlors and restaurants, including Dreamland.

In 1939 The Spokesman reported that he had been:

- Business agent and president of Waiters’ Union No 614, A.F. of L.

- A member of the Central Labor Union

- A joint executive board member of the Hotel and Restaurant Workers’ Union

- A member of the Urban League Board

- A member of the Masonic Lodge

- He conducted the Urban League Waiters’ School for two years

DREAMLAND CAFE

In 1939, with partner Thel Collins, he started the Dreamland Cafe. Dreamland did not have a liquor license, but was a fancy, dress-up establishment in the center of the city’s south side black community where everyone felt comfortable.

In 1940, when he registered for the draft for World War II, he reported that he was a waiter at the Curtis Hotel.

CASSISUS BAR AND CAFE

In 1946 he sold Dreamland to buy his own bar with a hard liquor license. He aspired to become the first black man to own a hard liquor license in Minneapolis, but the City Council put one obstacle after another in his way. One argument was that he was still the owner of Dreamland, which he wasn’t. Another was that he was a Communist, because he was friends with the head of the Communist Part in Minneapolis. (Being a strong Union man didn’t help this cause either.) One Alderman even had the nerve to say that black people should only be licensed for “barbeques, shoeshine parlors, and barbershops.”

Finally, after two years and spending all of his savings of $3,500, Cassius got the license, but it left him with no money to set up the bar. He went to Midland Bank and said that he wanted a loan of $10,000. The Vice Presidents laughed and said the only black man they’d ever loaned money to was Cecil Newman, editor of the Minneapolis Spokesman, and that was only $500. But Cassius was persistent and spoke to the Bank President, Arnulf Ueland, and within 15 minutes he had him convinced to give him the whole amount. The note was for 24 months but he paid it off in a year.

207 SOUTH THIRD STREET

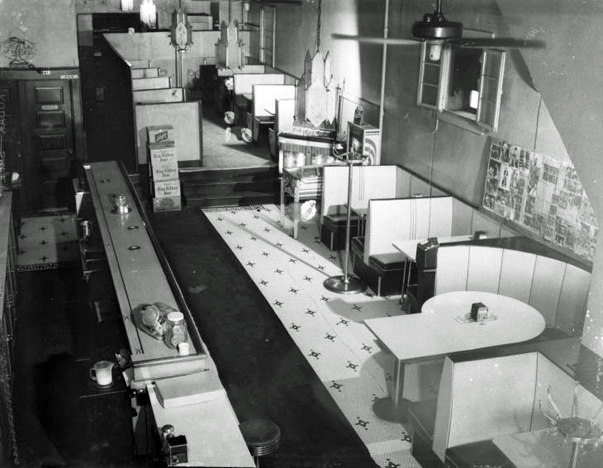

The Cassius Bar opened in 1946 in its original location at 207 So. Third Street in Minneapolis. The Strib described it as a “tough, black-run bar” that he overhauled in interior and reputation, and turned into a hangout for sports figures, performers, and politicians.

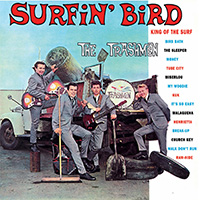

The Bamboo Room opened in September 1949. It was a jazz venue, featuring such local mainstays as Percy Hughes, Irv Williams, Oscar Frazier and the Four Notes, and the Rook Ganz Orchestra. Prince Rogers and his Combo performed there on Friday and Saturday nights in 1951.

It apparently went dark summers, as it had re-openings in September 1950 – ’53.

The Bamboo Room featured Oscar Frazier in 1954.

The extraordinary photo below is identified as “Cassius Bar and Playroom” and was taken by John F. Glanton. It is probably the original location.

318 SOUTH THIRD STREET

In July 1958 the bar was moved to 318 So. Third St. in Minneapolis due to redevelopment of the original area. The building, built in 1908, had two stories.

Kevin Diaz of the Star Tribune article described it:

In its early history, Cassius’ bar was known as a place where whites and blacks mingled in elegant surroundings, dressed in tuxedos and cocktail dresses. In its later history, headlines told of fights, shootings and one well-known police brutality case: A black police lieutenant, Ray Presley, publicly accused two off-duty white colleagues of drunkenness when they arrested a black patron there.

In the 1960s it was the site “Rhythm ‘n’ Blues Time,” a simulcast on KUXL featuring the best in R&B as played by Prime Minister Billy G.

In 1968 Cassius tried to relocate the bar to 401 E. Lake Street, which was outside of the City’s liquor patrol limits. That required a referendum among local residents, which he lost.

On June 20, 1980, the Cassius Bar closed for good. The area had declined for several years, and drugs, violence, and racial turmoil had taken over.

Anthony B. Cassius died on August 1, 1983.

McCREADY’S PUB

McCready’s was run by Pat Mus from about 1980 to 1986, and then sold it to Doc Holiday, who owned it to the end. The manager was Diane Schmidt, who said she had been working hard to “turn the place around.” She said that “It’s been a kind of ‘Cheers’-type place in the neighborhood. It attracts bankers, lawyers, blue-collar types…”

The building burned to the ground on Monday, October 14, 1991.

THE CHINESE GAMBLING DEN

On the second floor of 318 So. Third Street there was a hangout for the elders of the On Leong (Chinese) Merchants Association, accused by the FBI of a big-time gambling operation.

In 1980, five members of a Chinese street gang called the Ghost Shadows held up 150 guest at a Chinese New Year’s party on the second floor, ordering them to undress and hand over their valuables. Retired restaurateur Hugh Wong, working security for the On Leong, which owned the building, shot several of the robbers, who were captured by the police. Wong himself was shot to death four years later, and his killer has not been found. U.S. Marshals confiscated the building from the On Leong in 1990 as part of a national multi-million dollar gambling crackdown against many of the organization’s leaders, including Bloomington’s David Fong. (Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 15, 1991)