Labor Temple

117 Fourth Street SE

Minneapolis

Contrary to urban myth and confusion, the Labor Temple is NOT the current Aveda Institute. The Labor Temple was next to that corner building, at 117 Fourth Street SE, Minneapolis, now the Aveda parking lot.

THE AVEDA BUILDING

The photo above is the Cataract Masonic Temple on the corner of Central and 4th St. SE, 1950. This is the building that became what we now know as the Aveda Building, and still stands. In this picture, you can just see the edge of the Labor Temple next to it, on the right.

We actually got a tour of this building by an Aveda employee, who was convinced it was the former Labor Temple. Not only that, he said that Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix had played there, two acts that had never even played at the REAL Labor Temple! Urban Legends are hard to kill!

THE LABOR TEMPLE

EAGLES HALL

The Eagles Hall was built by the St. Anthony Eagles Aerie No. 1247 , which was different from the Minneapolis Eagles No. 34, which still exists today. At the time they began planning for the new building, the organization was located at 501 E. Hennepin Ave., and already had 2,000 members.

The Hall was built in 1923-1924, at a time when fraternal organizations like the Eagles, Masons, Lions, etc., were growing exponentially. The stated goal of the Eagles was not only to provide help to the needy, but to lobby for an old age pension to be provided by the State of Minnesota, in the amount of $25/month. These were in the days before Social Security.

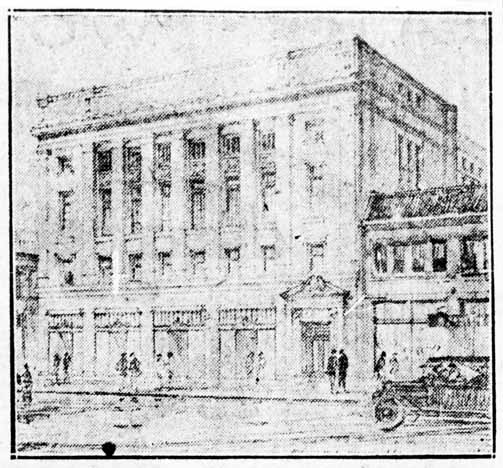

A sketch of the proposed new Hall appeared in July 1923. Note that the Cataract Masonic Temple does not appear to be to the left, and there is a building flush on the right.

1923

Original plans, drawn up by Fallows, Huey & MacComber, called for a four-story building:

- The first floor would have four storefronts to be rented out.

- The second floor lodge room would seat 500. The secretary’s office and other rental offices would also be on the second floor.

- The third floor auditorium would occupy a space of 78 ft. by 112 ft., with a large balcony, with a seating capacity of 2,500. A large dining room would also seat 500.

- In an unspecified area (perhaps in the basement) would also be a bowling alley, billiard and pool tables. (Minneapolis Daily Star, January 13, 1923)

On February 11, 1923, 325 new members were initiated into the St. Anthony Aerie. With 2,000 members already on the rolls, their goal was to have 3,000 members by June 1, 1923.

City records show that a building permit for an 88 ft. x 166 ft. foundation and floor slab was issued on June 20, 1923, and a permit for the construction of the lodge building was issued on September 29, 1923. The total cost of construction was expected to cost $150,000, most of which had been raised. The news report on the first permit said that the application specified that the foundation had to be of strength capable of supporting a three-story, concrete, brick and tile club house and is to be completed by the following fall, when erection of the clubhouse proper was expected to begin. (Minneapolis Daily Star, June 21, 1923)

Work had begun by July 1, 1923; R. Billingsby & Co., Minneapolis, were the general contractors. Specifications called for a 4 1/2 story reinforced concrete structure with brick exterior and Bedford stone trim. The cornerstone of the building was laid on December 2, 1923, by Mayor George E. Leach. The dedication address was made by Conrad H. Mann of Kansas City, the past grand worthy president of the order. At the dedication, another 273 members were initiated.

SALAMANDER STARTS FIRE !

Yes, started by a salamander and fed by some hay, a fire broke out at about 8 am on December 18, 1923, on the unfinished fourth floor of the lodge, causing an estimated $2,000 damage to the woodwork that held the concrete moulds in place and to some scaffolding. H.P. Stone, who lived directly across Fourth Street from the building, said that the heat from the fire was enough “to take the chill from the plate glass in the front door of his house.” (Minneapolis Daily Star, December 18, 1923)

1924

The building was apparently in use in 1924, as there were boxing matches advertised in October, featuring 30 amateurs. Boxing would be a popular activity in the building, in addition to dances.

The official dedication of the new hall was somehow delayed until December 15, 1924, and the cost was reported to be $300,000 – $100,000 over budget. 2,000 people attended the dedication ceremony, again attended by Mayor Leach; it appears that in addition to the Old Age Pension, the Eagles were also advocating for a child labor amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Musical numbers were presented at the ceremony.

1925

DANCE HALLS AND MORALITY

The next order of business was to apply to the City Council for a dance hall license. This led to a two-hour session of some delightfully fiery rhetoric on the part of some of the Aldermen – or, as the Daily Star described it, “a red hot two hours’ scrap.” The problem was that the hall was considered too close to the U of M and would draw students and harm their morals. Mr. Hawley declared that, “with the possible exception of the divorce evil, the public dance hall is the worst menace confronting the American nation.” It leads to “promiscuousness, [and is] responsible for so many young people being led astray.”

Mr. Bastie countered that “they provide a source of recreation for the poorer employed girls who have no homes of their own.”

Mr. Gisslen pointed out that it would be “better for the students to dance in Eagles Hall than in some of the downtown halls.”

Mr. Hanscom noted, “The membership of this organization includes many prominent officials and citizens … it is inconceivable that it would permit anything detrimental to it…” Store that away for later.

The upshot is that the Eagles got their dance hall permit, but then the City Attorney opined that they didn’t need one if they conducted the dances themselves for their own members of if they rented the hall to other organizations for their own members. So the Eagles, not wanting to pay for a license every year, gave it back to the City. (Minneapolis Daily Star, February 14 and 25, 1925)

IT’S A RAID!!

On April 16, 1925, Federal Prohibition agents “battered down the doors” to the Eagles’ Hall and found either 1) members quietly playing cards, or 2) up to 200 members buying beer, whiskey, and moonshine as if they were in a pre-Prohibition saloon. Some of those on scene were arrested for creating a nuisance, and seven plead guilty.

None of the trustees were there, but when trustee H.L. Lennon heard rumors that the Feds were looking for him, he went down to see what was what, and what was what was that he was arrested. What was particularly galling was that Mr. Lennon was a State Senator (one of those prominent officials and citizens). Lennon expressed great outrage in a long article in the Minneapolis Daily Star (May 8, 1925).

In November 1925, ten went on trial: eight officers (including the chaplain), and two employees. Testifying against them were three Prohibition agents who had gone “underground” and joined the Eagles so they could find out about the basement bar. (Minneapolis Tribune, November 4, 1925)

Five of the defendants (including the chaplain) were dropped), and after a four-day trial, the president, secretary, an employee, and two trustees (including Senator Lennon) were convicted. The maximum sentence was a year and a day. Lennon served some time but got a Presidential pardon.

LET’S DANCE!

The large hall on the third floor was rented out to groups who held public and private events. The Eagles (and later the owners of the Labor Temple) were remarkably open minded about the kind of music they hosted, which included:

- Old Time (perhaps polka, since it was often presented by Whoopie John)

- Craziness (Thorstein Skarning’s Norke Hillbilly band!)

- Dance Orchestras

- Jazz

- Rhythm & Blues

- Rock ‘n’ Roll

Many of these dances were advertised in the City’s regular daily newspapers (the Minneapolis Tribune/Daily Star/Star), and the Minnesota Daily, put out by students at the University of Minnesota.

But many others were only found in the Minneapolis Spokesman, which was the City’s Black newspaper, founded by Cecil E. Newman in August 1934. Thanks to my friend Ellen Lewis, I found about about this paper and accessed it on microfilm at the Minnesota Historical Society. The amazing shows I found there, especially in the 1950s, made me wonder if the white population of Minneapolis even knew about them. The City was pretty well segregated when it came to entertainment, which is why the black community relied on their own dances in places like the Labor Temple and the South Side Auditorium; with some exceptions, they were not generally welcome in the clubs downtown. There are even stories about celebrities like Nat King Cole being turned away. I have no way of knowing whether these dances were mixed or not. If I had been the right age, I would have wanted to be there!

Please note that dance season usually started in late September/early October. Summers were too hot to hold regular dances, throughout the entire life of the building.

1927

The ad below announced the opening dance of the 1927 season. Wonder what the Kloss Novelty Orchestra sounded like?

The ad below, also from 1927, announces dancing at the New Eagles’ Ballroom every Thursday, Saturday, and Sunday. Music was provided by the popular Eli Rice – his orchestra at this gig was called the 11 Dixie Cotton Pickers.

1930

Permit cards show that in 1930 there was an entry for an undertaker’s business on the ground floor.

In 1930 the Ballroom was apparently still considered new. Eli Rice’s band was very popular around town. These dances were broadcast remotely over WDGY radio.

1931

In April 1931, music for dancing was provided by the Eagles Orchestra, broadcast remotely over WDGY radio.

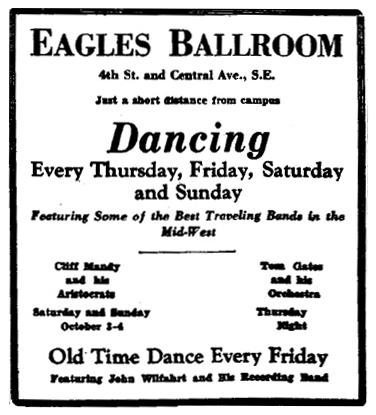

In 1931 and 1932, the Eagles Ballroom features “Old Time Dances” with the legendary Whoopie John on Fridays, and dances with the music of the popular Cec Hurst Orchestra on Saturdays and Sundays.

1933

Before the National Guard Armory was built in Downtown Minneapolis, there was the Kenwood Armory by the Parade grounds. It was a grand building, but built on an unstable foundation, and in 1933 it was condemned by the City. Before the new Armory could be built, the National Guard needed a place to drill, and one of those places was the Eagles Hall.

Even before the Hall was purchased by the labor unions, it was a popular meeting hall and event center for the various unions in the City. The dance below was under the auspices of the Railroad Trainmen.

The Ballroom opened for the 1933-1934 season in October with Old Time dancing with Whoopie John on Fridays and Matt Delong’s Orchestra on Fridays and Saturdays.

1935

On October 31, 1935, Bud Strawn’s Orchestra provided the music for an Old Time Dance, sponsored by the East Side Progressive Club.

1936

The Hall hosted many wrestling matches over the 1936-1937 season.

1937

On January 17, 1937, a 27-year-old young man from St. Paul fell over a third floor banister to his death while exiting a dance.

1938

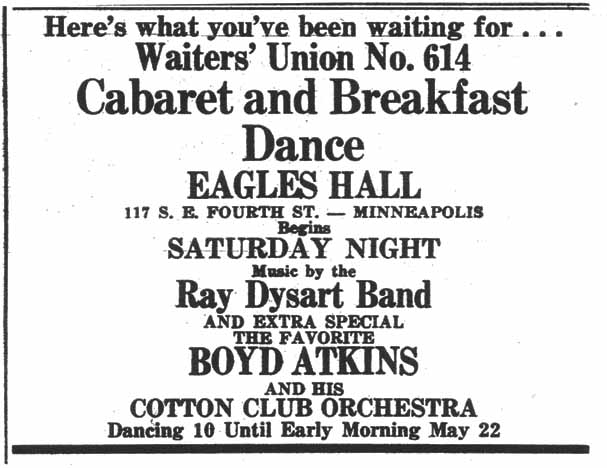

Waiters’ Union No. 614 sponsored a Cabaret and Breakfast dance on May 21, 1938. Ray Dysart’s orchestra played for the first half of the dance, with Boyd Atkins’ Cotton Club orchestra playing the second half. The Cotton Club band was described in the Spokesman as “one of the top bands in this section of the country,” making its “first appearance at a public dance for several months.”

1939

JITTERBUG JINX

The first annual National Negro Jitterbug Dance Contest was held at the Eagles Ballroom on February 13 and 14, 1939. Lloyd Hunter’s 14-piece band, featuring an all girl floor show, provided the music. “50 Contestants Will Jitter,” with $100 in cash prizes. (Minneapolis Spokesman, January 20, 1939)

However, it turns out that Ray Dysart, who promoted the contest, went back on his word about the $100 prize. Seems that cold weather kept attendance down, and Dysart decided to call off the contest. The rest is a little murky: “He offered $5 to the three finalist couples, he said, and it was accepted. The couples, he said, insisted, however, on going on with the contest.”

Anyway, Mrs. Lucia Bowen went to court, suing Dysart for $55, which was first prize in the contest, on behalf of her son Donald, who won the contest, with his sister Barbara as his partner. The judge took the question under advisement. (Minneapolis Star, March 24, 1939)

Internationally-known dancer Jessie Scott appeared as guest star at a dance at the Eagles Hall on April 9, 1939. She recently returned from a European tour. She last appeared in Minneapolis six years prior “and was the toast of the town.” (Minneapolis Spokesman, April 7, 1939)

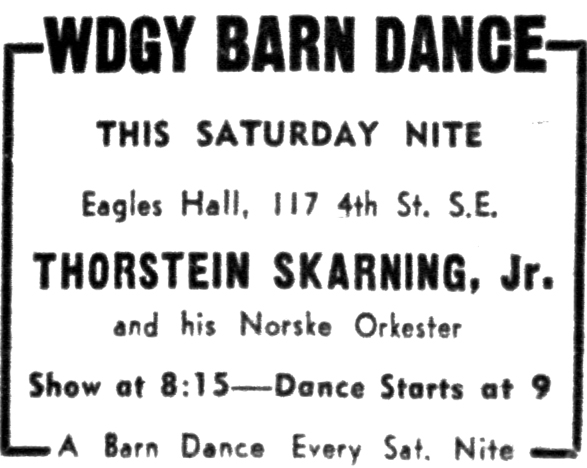

Diversity was evident when Thorstein Skarning, Jr., king of the Norwegian Hillbillies, brought his WDGY Barn Dance show to Eagles Hall on Saturday nights in 1939.

On November 5, 1939, the Ballroom began hosting Old Time Sunday night dances.

1940

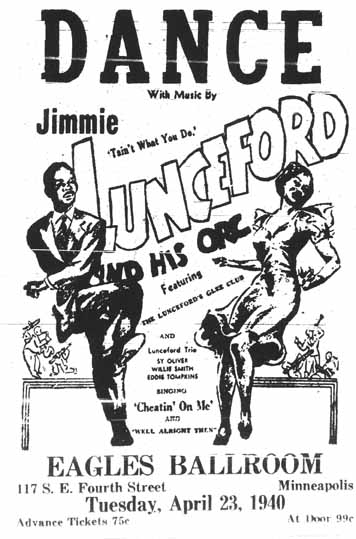

Jimmie Lunceford’s Orchestra came to the Eagles Ballroom on April 23, 1940. Man, does that look like fun!

Unfortunately, one of the promoters of the Lunceford show took $500 of the receipts home with him and hid them in a closet. He went out, robbers went in, and the $500 went missing. Police had two suspects. (Minneapolis Spokesman, April 26, 1940)

Thorstein Skarning continued his Saturday night dances in the winter of 1940.

1941

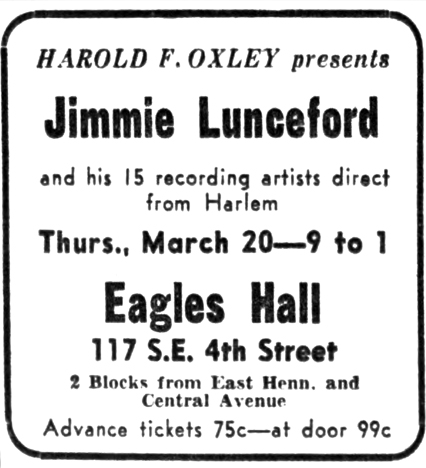

Jimmie Lunceford returned to Eagles Hall on March 20, 1941. A blurb in the Minneapolis Star that day announced:

Jimmie Lunceford, probably one of the best colored orchestra leaders in the business, in town today for his appearance tonight at the Eagles hall, brought with him a curious conviction: Jazz music is becoming tamer. Bill Taylor, local impressario, has rustled a packed ballroom for the Lunceford performance tonight and will have probably 2,000 listeners and dancers.

Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy was a famous stage and radio band, featuring vocalist June Richmond. The orchestra appeared for an Emancipation Ball at the Eagles Hall on August 4, 1941. (Minneapolis Spokesman, August 1, 1941)

Dr. W.D. Brown was elected Mayor of Bronzeville at the second annual Inaugural Ball, held on Thanksgiving night, November 20, 1941, at the Eagles Hall. Check the link for the fascinating story of the Mayor of Bronzeville!

1942

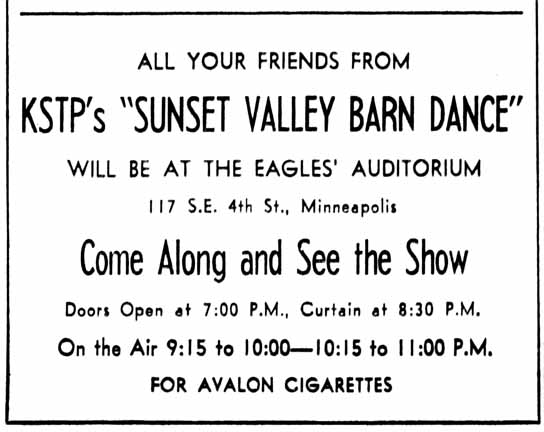

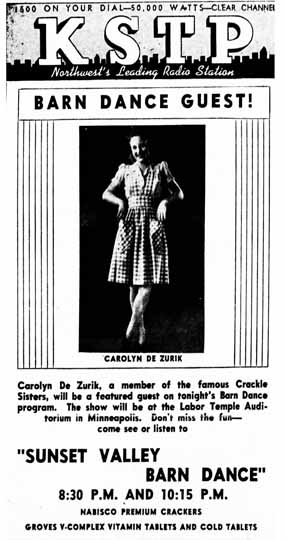

The Barn Dance also appeared at the Eagles Auditorium on May 23, 1942, presented by Shell Oil and Avalon Cigarettes.

THE LABOR TEMPLE

On April 8, 1942, the Eagles sold the building to the Labor Temple Association for $65,000. It is unclear just what happened to this Aerie of the Eagles. It appears that it was to replace a building referred to in a dance ad in the Spokesman as the “Labor Hall.” That ad, dated December 22, 1941, gave the address of the Labor Hall as 720 4th Street So., which is a block northwest of the present Vikings’ football stadium.

Remodeling the Eagles building for occupancy by 43 unions was expected to be completed by July 1, 1942. Plans to house the union affiliates of AFL under one roof had started 17 years prior. At one time there was a plan to take over the city’s old East High School building, located at Fourth Ave. So. and Seventh Street, but it had recently fallen through. East High had closed in 1924. (Strib April 19, 1942)

On June 9, 1942, the deed for the hall was registered in the name of the Minneapolis Labor Temple Association. The building would hold offices for 40 to 50 labor unions and would be remodeled to include 11 meeting halls. The building would be renamed the Olson Memorial Labor Temple in honor of the late Governor Floyd B. Olson. (Minneapolis Star, June 9, 1942)

A 25th Anniversary booklet published in about 1968 revealed that one of the large halls was called Cramer Hall, named after Robley Cramer, “editor of the Minneapolis Labor Review and one of the most militant and fearless labor leaders that the movement ever produced.” The other hall was named after Richard Wiggin, former city attorney of Minneapolis.

In 1942, the new owners continued to rent out the ballroom for concerts and dances.

FLETCHER HENDERSON

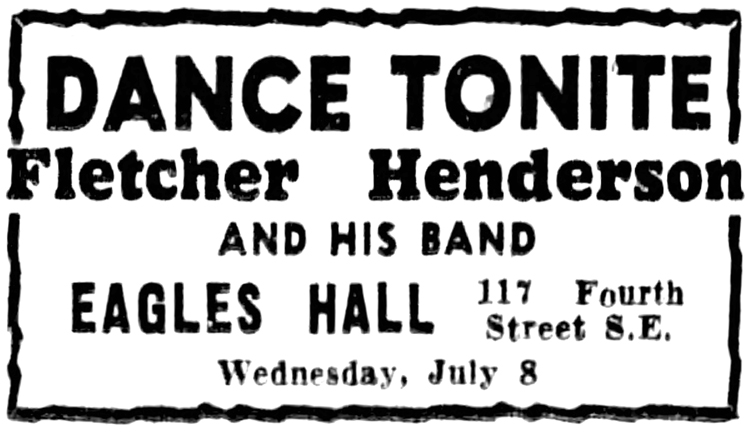

Fletcher Henderson and his 14-piece Orchestra came to the Eagles Hall on July 8, 1942. Henderson’s band was “the first ‘name’ band the localites had an opportunity to dance to for several months,” reported the Spokesman.

Fletcher Henderson possesses the ability which few leaders have to inspire their men to their best efforts at all times. With a peculiar rhythmic swing on the piano that is nevere forgotten entirely by anyone who ever dances or listens to it, he can set a ballroom or theatre afire with his interpretation of both popular and old favorites. (Minneapolis Spokesman, July 3, 1942)

Apparently the name of the hall hadn’t changed yet:

A nice gesture of Fletcher Henderson before leaving town to report for a picture at Paramount studios, is to play tonight for a Negro dance at the Eagle’s hall. The town has been talking about Fletcher and his piano playing, his quiet reserved manner. (Minneapolis Star, July 8, 1942)

1943

Duke Ellington was scheduled to make an appearance at the Labor Temple on Friday, September 18, 1953. The Tribune reported:

Duke Ellington, in the minds of a lot of jazz aficionados the top guy of them all, comes to Minneapolis Friday for an 8:30 concert in Minneapolis Labor Temple, a presentation of D. P. Black, who plans two other fall concerts . . . Ellington for a couple of decades has been in a class by himself as leader, composer, and arranger. His current band includes 15 men and three vocalists, and his program will include such things of his own as “Mood Indigo,” “Liberian Suite,” and “Perfume Suite” . . . He will appear at Sister Kenny Institute Friday afternoon, and will be interviewed by Jack Thayer at 4 pm on WTCN-TV. (Minneapolis Tribune, September 13, 1953)

KSTP BARN DANCE

1944

1946

Ernie Bjorklund’s band was some kind of local/house band that circulated through all the ballrooms in town. An ad shows Ernie playing at the Labor Temple on Saturday nights, the CIO Hall on Sunday nights, and the Marigold Ballroom every Monday and Thursday. Salad days for Ernie’s boys! This scheduled continued to April 1947.

1947

The Elks Antler Guard gave a big dance on February 17, 1947, with Joe Broadfoot and His Orchestra providing the music. The venue on the notice in the Minneapolis Spokesman was given as the “Labor Temple, Formerly Eagles Hall.”

April 16, 1947, brought Sy Oliver to the Temple:

Sy Oliver, best known as an arranger for people like the Dorseys, brings his new orchestra to the Labor Temple Wednesday night. With him will be Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers. (Strib April 12, 1947)

Note that one of the places to buy tickets was the Dreamland Cafe, one of my favorite buildings!

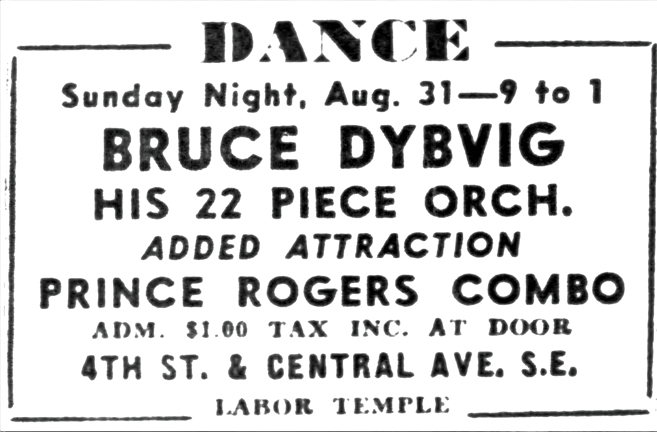

A dance was held on August 31, 1947, with music by Bruce Dybvig and his Orchestra and the Prince Rogers Combo. Dybvig was a white big-band leader; Prince Rogers was the stage name of John L. Nelson, the father of Prince Rogers Nelson. Wikipedia says that Nelson’s career became active in 1948, but this ad shows that it was at least 1947.

A dance at the Labor Temple on October 31, 1947, featured Bessie Givens and a 9-piece orchestra.

The Labor Temple was the site of the Elks’ Big Battle of Music on November 24, 1947, with the Percy Hughes Band battling it out with the New Prince Rogers Orchestra.

The Mayor of Bronzeville Fifth Annual Ball was held on November 27, 1947, at the Labor Temple.

1948

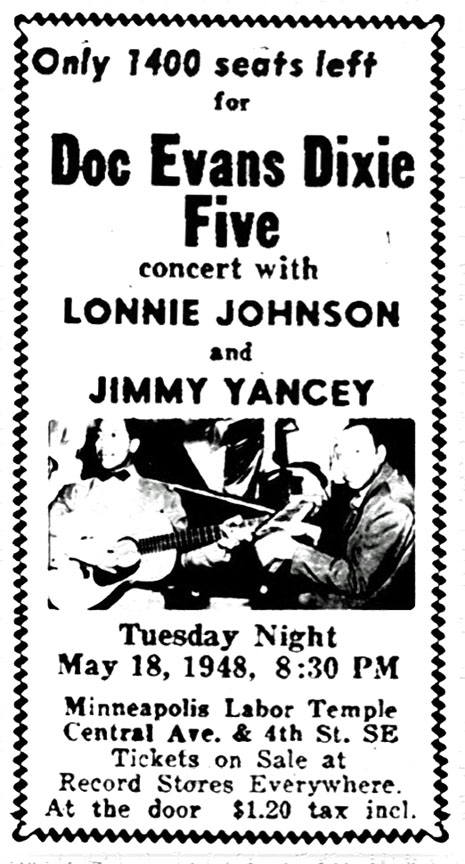

Doc Evans was a Dixieland artist, Lonnie Johnson was a “blues shouter,” and Jimmy Yancey was a boogie-woogie, eight-to-the-bar piano player. It was Evans’ first appearance since the “We Call it Jazz” concerts in the Fall of 1947.

The Elks held a pre-convention dance at the Labor Temple in May 1948, with music by Arty “Fritz” Watkins and His Northern Lights Orchestra.

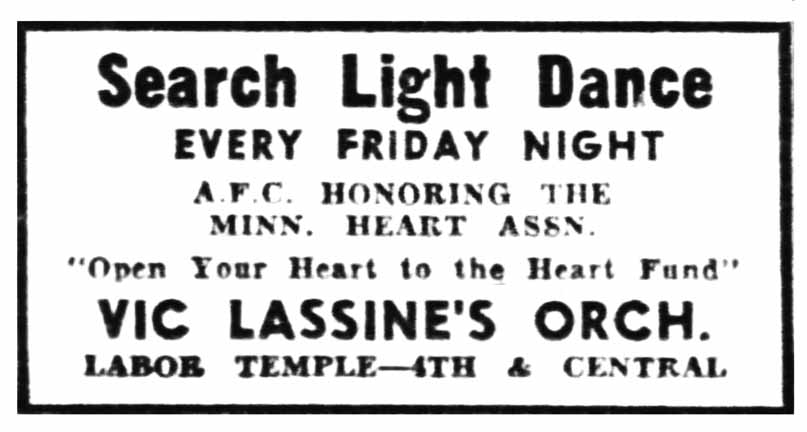

Vic Lassine’s Orchestra provided the music for dancing every Friday night in June 1948.

A Thanksgiving Eve Ball at the Labor Temple on October 24, 1948, featured Lottsa Poppa! (Nat Towles) and his orchestra.

1949

A pre-Fourth of July dance on July 2, 1949, at the Labor Temple featured Nat “Lottsa Poppa” Towles and his new orchestra and entertainers.

Percy Hughes had spent the winter of 1948-49 as the house band at Snyder’s Night Club in downtown Minneapolis and the summer of 1949 at Bar Harbor in northern Minnesota. In September he returned to Minneapolis and played at the Labor Temple, again with singer/wife Judy Perkins.

1950

This ad was in a story about a sudden proliferation of Bingo games in the City.

The DFL Rally featured entertainment brought in from the clubs on Hennepin Ave. Hmmm…..

The Minneapolis Socialite Club sponsored an Easter Sunday Dance at the Labor Temple, featuring the music of Percy Hughes.

A “Pre-Mom Day Dance” at the Labor Temple was sponsored by the Friendly 16 Club on May 14, 1950. Music by Percy Hughes and His Rhythm Boys featuring Dick Mayes.

A June 3, 1950, show featuring Nat “Lottsa Poppa!” Towles Orchestra and Revue with the Edwards Sisters and Tiny Kennedy, King of the Blues Singers, took place at the Labor Temple.

A “Battle of Swing” was swung on September 3, 1950, at the Labor Temple from 3pm to 1am. Percy Hughes and his orchestra battled it out against Bob Bass and his orchestra.

A public jazz concert and dance was held on September 25, 1950, featuring Rook Ganz “and a group of local jazz artists.” Frances Fisher was the vocalist, and Tommy Lewis was m.c.

WEBSTER AND BLACK

From October 1950 to 1956, Rufus Webster and/or D.P. Black brought major national rhythm & blues acts to Minneapolis, almost exclusively to the Labor Temple. Will Jones described Webster as a pianist at Cassius’ Bamboo Room, and that he was going into the promotion of jazz concerts with name artists. Follow the link above to read much more about Rufus Webster. I have not found anything about who D.P. Black was – perhaps Deborah Black?

Shows with an * were promoted by Webster and Black.

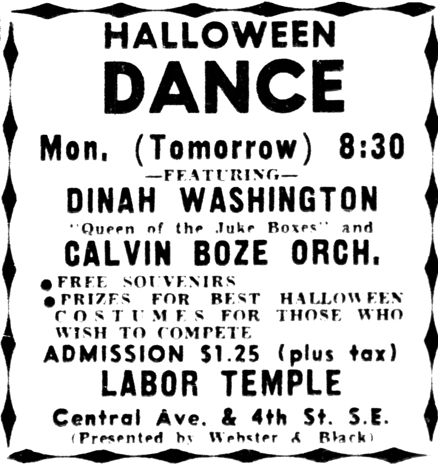

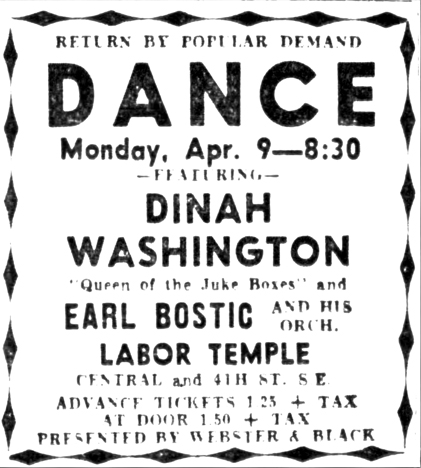

A pre-Halloween dance was held on October 30, 1950, at the Labor Temple featuring Dinah Washington (“Queen of the Juke Boxes”) and the Calvin Bose Orchestra. * This was Webster and Black’s first promotion.

The Duke and Dutchess Club sponsored a Thanksgiving Matinee Dance at the Labor Temple on November 23, 1950, music by Percy Hughes.

1951

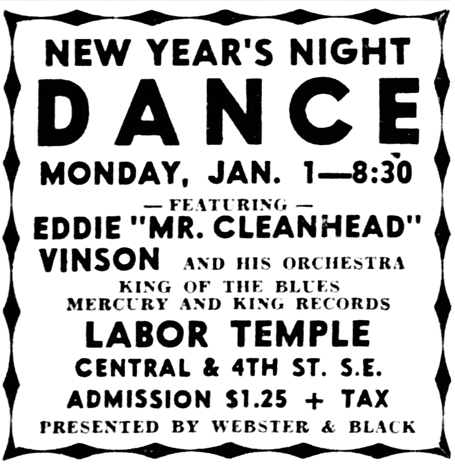

Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson and His Orchestra, January 1, 1951 *

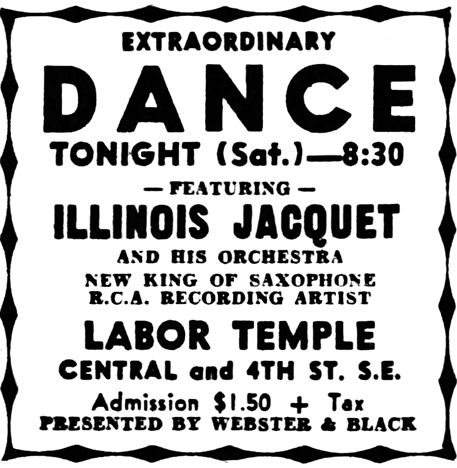

Illinois Jacquet and His Orchestra, January 27, 1951 *

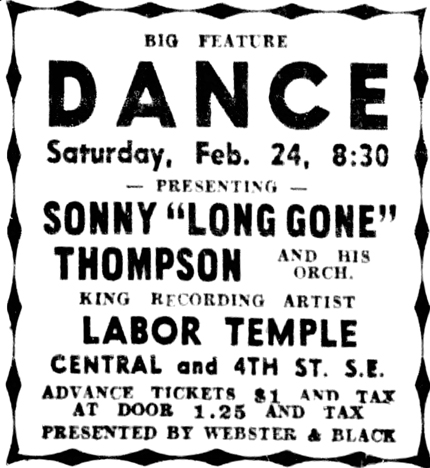

Sonny “Long Gone” Thompson and His Orchestra, February 24, 1951 *

Lowell Fulson and His Orchestra featuring Ray Charles, March 9, 1951 *

Earl Bostic and His Orchestra featuring Dinah Washington, returning by popular demand, April 9, 1951

Cootie Williams and the Ravens, May 29, 1951. “This is Double! The Greatest Attraction of the Year! This is a Sensation and You’ll Enjoy It!!”

BATTLE OF THE BLUES

The “Biggest Battle of the Blues” was staged on July 8, 1951, featuring: *

- Wynonie Harris, “Mr. Blues”

- Annie Laurie, known for her rendition of “Since I Fell for You” and “I’ll Never be Free”

- “Sticks” McGhee – His big hit was “Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee.”

- Eddie Durham and His Orchestra

By this time, Harris had recorded:

- “Who Threw the Whisky in the Well”

- “Grandma Plays the Numbers”

- “Good Rockin’ Tonight”

- “I Feel That Old Age Coming On”

Minneapolis Spokesman, July 6, 1951

Roy Milton, “Mr. Blues Himself,” and His Orchestra, with dynamic vocalist Lillie Greenwood and Johnny Rogers, “the wizard of the guitar,” August 11, 1951

Roy Brown and His Mighty, Mighty Men, September 1, 1951 *

Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, September 22, 1951 *

Percy Hughes and His Orchestra performed at a special NAACP Membership Dance on September 24, 1951

Ivory Joe Hunter and His Orchestra, October 20, 1951

Tom Archer (Wynonie Harris’s sax man) and George Floyd (vocalist with Fletcher Henderson), November 25, 1951

VANDALS WREAK HAVOK AT MPLS. LABOR TEMPLE

Joe Thomas and His Orchestra, December 31, 1951 *

Despite the presence of three police officers, “hoodlums” tore plumbing and a radiator from the wall in the men’s lavatory while the New Year’s Eve dance was going on. “Police believe the vandalism was premeditated and might be the result of a grudge against promoters Webster and Black who have been bringing dance attractions to the hall for the past year.” A “gang of young toughs” broke a pane of glass in a door to get in without paying admission. (Minneapolis Spokesman, January 4, 1952)

1952

Shows with an * were promoted by Webster and Black.

Duke Ellington, January 23, 1952

Arnett Cobb and His Orchestra, March 14, 1952

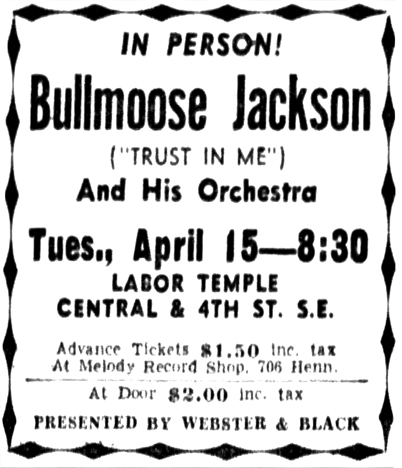

On April 15, 1952, Bullmoose Jackson made an appearance at the Labor Temple. *

Joe Liggins and the Honeydrippers, May 1, 1952

Preston Love and a Mammoth Floor Show with torch singers, dancers, comedians, May 17, 1952 *

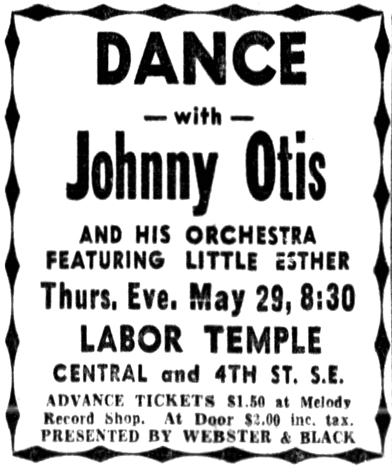

Johnny Otis and His Orchestra, Pre-Decoration Day dance, May 29, 1952 * Otis’s vocalist was Little Esther, a/k/a Esther Phillips. Others in the cast were Mel Walker and Willie Mae Walker. “Otis is known as the only white conductor of a Negro orchestra.” (Minneapolis Star, May 27, 1952)

Todd Rhodes and His Orchestra, June 14, 1952 *

Roy Milton and His Orchestra, with Lillie Greenwood and Johnny Rogers, July 19, 1952

Gene Ammons and His Orchestra, September 14, 1952 *

Jimmy Witherspoon and His Great Orchestra, October 18, 1952 *

Hal “Cornbread” Singer and His Orchestra, “America’s Most Exciting Saxophone Star,” October 4, 1952

Sonny Thompson and His Orchestra, November 1, 1952

Roy Milton and His Orchestra, November 10, 1952 *

Willis “Gator Tail” Jackson, November 22, 1952. Ellis Attraction. “Gator’s Groove” – whatta tune!

Todd Rhodes and His Orchestra, featuring Little Miss “Sharecropper,” who was pictured but not named, but we know her as LaVern Baker. The show was on November 7, 1952. *

Hal “Cornbread” Singer, December 27, 1952

1953

Shows with a * were promoted by Webster and Black. Those with ** were by D.P. Black only.

Jimmy Witherspoon, January 1, 1953 *

Jimmie Forrest (“Night Train”), February 1, 1953 *

Leo “Cool Leo” Parker and His Orchestra, March 7, 1953

The Just For Fun Club sponsored a Beaux Arts Costume Ball on March 22, 1953, with Veet Williams and the All Stars.

Jimmie Forrest, March 26, 1953 **

Sonny Thompson (“Long Gone”) and His Orchestra, March 28, 1953. Ellis Attractions

The Little Esther Unit featuring Little Esther, H-Bomb Ferguson, and Tab Smith and His Orchestra, April 17, 1953 **

5 Royals (“Baby Don’t Do It”), Arnett Cobb and His Orchestra, May 1, 1953 **

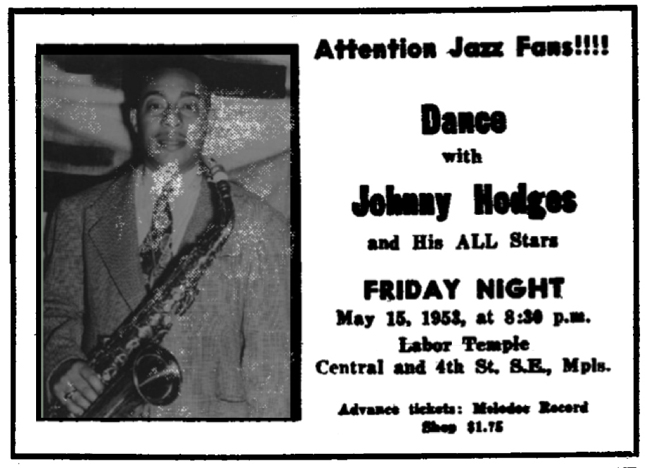

Johnny Hodges and His All Stars, May 15, 1953 **

Anna Mae Winburn and Her Sweethearts of Rhythm, May 24, 1953 **

Lowell Fulson, Lloyd Glenn and His Orchestra, May 30, 1953 **

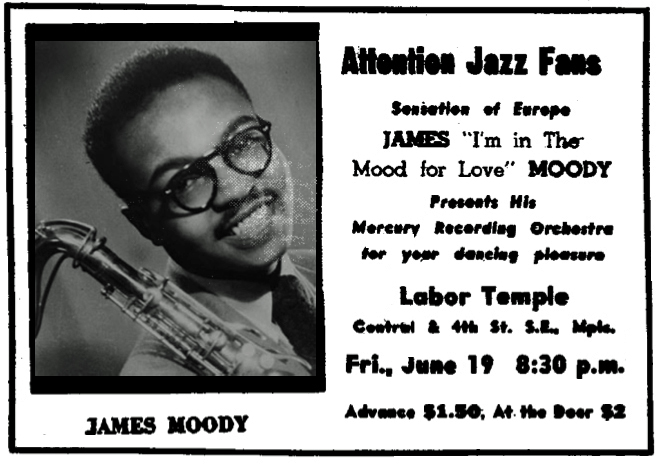

James Moody and His Orchestra, June 19, 1953 **

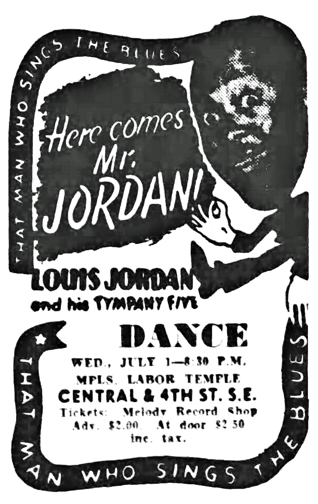

LOUIS JORDAN

Louis Jordan (“The Man Who Sings the Blues”) and His Tympany Five appeared for a dance on July 1, 1953 ** Jordan was extremely popular in the ‘Cities, having already appeared on:

- November 24, 1952 at the St. Paul Auditorium

- April 12, 1953, at “The Biggest Show of ’53” at Radio City with Ella Fitzgerald, Frankie Laine, Woody Herman, and Dusty Fletcher

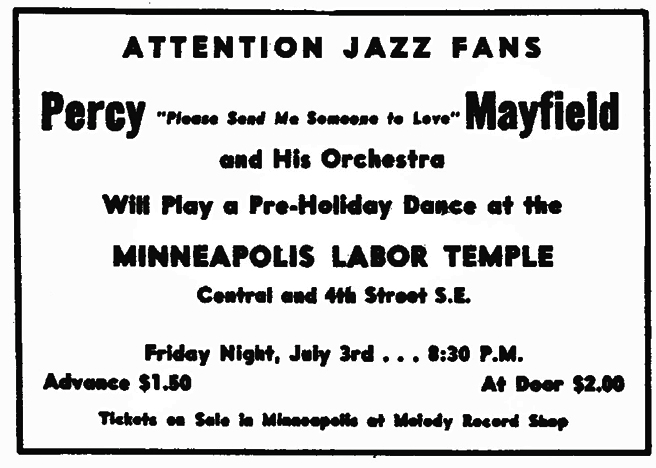

Percy Mayfield and His Orchestra, July 3, 1953 **

The Clovers with Eddy Boyd’s Orchestra, July 11, 1953 **

Todd Rhodes (“Trying”) and His Orchestra – first time in Minneapolis since his Meteoric Rise in the Juke Box Field – Ellis Attractions

Roy Milton and His Orchestra featuring Camille Howard, August 2, 1953 **

Dinah Washington and Her All-American Trio, August 15, 1953 **

Earl Bostic and His Orchestra, September 5, 1953 **

DUKE ELLINGTON, September 18, 1953. **

Ellington’s band included 15 men and three vocalists, and his program included original compositions such as “Mood Indigo,” “Liberian Suite,” and “Perfume Suite.” Earlier in the day he planned to visit the Sister Kenney Institute and be interviewed by Jack Thayer on WTCN-TV. (Minneapolis Tribune, September 13, 1953)

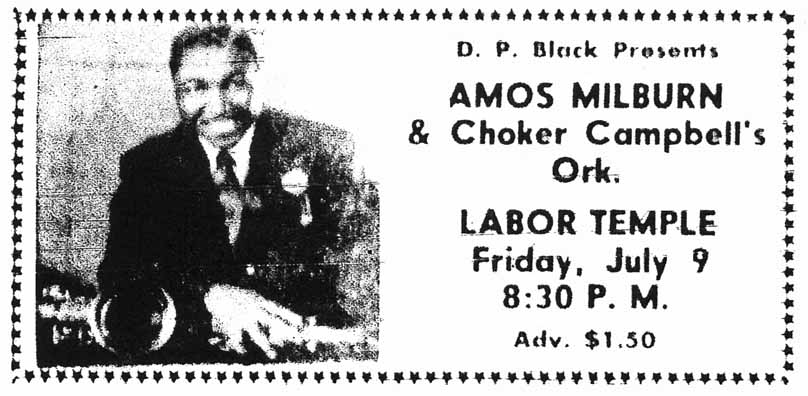

Amos Milburn, September 19, 1953 – first appearance in the Twin Cities by request of many dance fans. **

Johnny Otis and His Orchestra, featuring Marie Adams, October 3, 1953 **

Preston Love, “The Happy Boy with the Horn” and His Orchestra, October 25, 1953 **

Tiny Bradshaw, Rhythm “King” of Kings on Records and soloist Big Tiny Kennedy, November 27, 1953

5 Royals and Charlie Ferguson’s “All-Girl” Orchestra, December 26, 1953 **

1954

Shows with an * were promoted by D. P. Black.

The Clovers, January 22, 1954 *

Johnny Ace and His Orchestra featuring Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, Blues Singer Supreme, February 19, 1954

Roy Milton and His Solid Senders, featuring dynamic vocalist Lillie Greenwood and Johnny Rogers, the Wizard of the Guitar, February 26, 1954 (annual appearance) *

The Orioles, March 4, 1954 *

“Blues Sensational” Lowell Fulson and His Orchestra – “The Big Hit in Swing Jazz in the Biggest Musical Entertainment of the Spring Season,” March 19, 1954

Johnny Otis and His Orchestra featuring Marie Adams, March 26, 1954 *

Cootie Williams and His Orchestra featuring Eddie “Mr. Clean Head” Vinson, March 30, 1954 – “This is the Dance!” *

Red Allen and His Orchestra, Easter Matinee Dance *

Dinah Washington and Orchestra Matinee Dance, May 2, 1954 *

Ruth Brown, May 12, 1954 *

T-Bone Walker and Checker Campbell’s Orchestra, May 23, 1954 *

Todd Rhodes and His Orchestra, May 28, 1954

Faye Adams with Joe Morris and His Orchestra, June 18, 1954 *

Amos Milburn and Choker Campbell’s Orchestra, July 9, 1954 *

The Ravens, July 24, 1954 *

The Spiders and Memphis Slim’s Orchestra, August 28, 1954 *

Eddie “Mr. Cleanhead” Vinson and the Cootie Williams Orchestra, September 3, 1954 *

The 5 Royals with Tab Smith’s Orchestra, September 18, 1954 *

Jimmy Coe and His Orchestra, November 6, 1954 *

BIG JAY McNEELY BENEFIT

On November 7, 1954, a benefit dance was held to raise funds for Big Jay McNeely and his band, who lost all their instruments, music, and clothing at a fire at Vic’s and were left stranded in Minneapolis. The benefit was organized by A.B. Cassius, who hoped to raise enough to get the musicians back to their homes and “maybe make a down payment on some new instruments.” (Minneapolis Spokesman, November 5, 1954)

Will Jones reported:

Musicians from all over town will work free to provide continuous music from 4 pm to 1 am. There have been donations by bartenders, cooks, waters and other bar and restaurant workers and their unions. Meanwhile, there’s been some doubt whether Big Jay’s group will be on hand for the event. They’re busy lining up one-nighters to keep themselves busy – with borrowed instruments. Only McNeely’s saxophone was saved from the fire. He keeps it with him all the time.

Roy Milton and His Orchestra featuring dynamic vocalist Lillie Greenwood and Johnny Rogers, Wizard of the Guitar, November 28, 1954 *

1955

Shows with a * were promoted by D. P. Black.

Bullmoose Jackson, February 17, 1955 *

King Kolax and His Orchestra, direct from the East Coast, March 25, 1955

Percy Mayfield and His Orchestra, April 1, 1955 *

B.B. “Blues Boy” King and His Orchestra, April 11, 1955

Sonny “Long Gone” Thompson plus Lulu Reed, April 30, 1955

Ruth Brown, Griffen Brothers, May 26, 1955 *

Choker Campbell and His Orchestra featuring Lowell Fulson and his Guitar, October 23, 1955

Tiny Bradshaw and His Orchestra featuring “Little” Tiny Kennedy, October 28, 1955 *

Gene Ammons and His Orchestra plus the Spaniels, November 26, 1955 *

1956

Shows with a * were promoted by D. P. Black. By the way, the story about the May 27 scramble below, gives us about the only clue about the mysterious D.P. Black. It names Patricia Black of D.P. Black Presentations, 3619 Portland Ave. This may have been Patricia’s home address, though (they did that all the time in the newspapers) – it’s a duplex built in 1924.

Drifters and Willie “I Don’t Know” Mabon, January 1, 1956 *

WLOL RECORD HOP

Will Jones:

WLOL Disk Jockeys seem to think some of their listeners don’t get enough of the top 40 tunes during the week. So they’re promoting a Disk Jockey hop in the Labor Temple on Saturday night. They’ll charge the fans admission to come watch them play the same records they play all week for free. There will be some live rock-and-roll music by a group called the Big Five Mellowmen.

This great event took place on April 21, 1956!

DANCE HALL ROCK ‘N’ ROLL: BOOTH ROCKS AND COINS ROLL

The Midnighters with Cal Green’s Orchestra, May 27, 1956. *

Turns out the band’s bus broke down en route from South Bend, Indiana, and the 5:00 dance was delayed for hours. Suddenly the ticket booth, manned by Carl Cockrell, was upended and at the end of a mad scramble, $115 was missing from the till. Cockrell blamed the melee on a few “energetic youngsters,” not people wanting refunds. Finally the musicians arrived and “broke into the rollicking beat of ‘Dance if You Want to Dance.’ The customers did, until midnight.” (Minneapolis Star, May 28, 1956)

Ernie Freeman and His Orchestra Plus the Coasters, July 21, 1956 *

Ray Charles and His Orchestra, August 21, 1956 *

Tiny (Mr. Soft) Bradshaw and His Orchestra, Added Attraction “Mr. Bear.” Biggest Ball of the Year – Minnesota-Iowa Shriners Potentates Ball, September 1, 1956

Jay McShann and Priscilla Bowman, September 8, 1956 *

Charles Brown and His Orchestra, November 16, 1956 *

Bill Haley and His Comets – date unknown, but David Anthony Wachter says the show was promoted by T. B. Skarning.

1957

FRENCHY’S MISADVENTURE

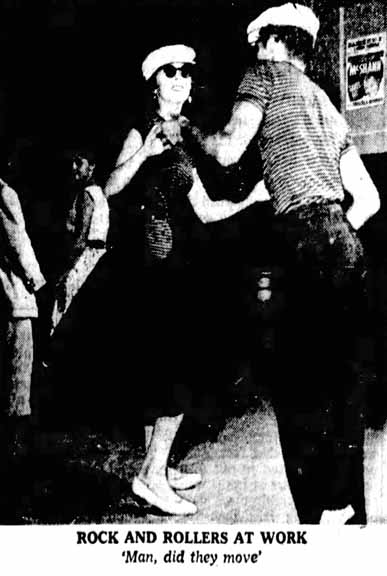

This is the unfortunate story of Lee Thomas “Frenchy” Speicher, whose “real cool” calypso and rock ‘n’ roll dancing at the Labor Temple got him captured on a murder charge.

It all came down this way. It was July 4, 1957, and Frenchy was at North Commons watching the fireworks. An acquaintance named “Lucky or Bucky” came up and asked him if he knew where to get some whisky, so he asked three fellows if they had any for sale. They said yes, took $5 from Lucky, went to their car, but they drove away. Frenchy gave chase, and when the three guys stopped, Lucky went at them with a club.

Frenchy got out and, “as a show of strength,” showed the men in the car his nine-millimeter German luger. As he cocked it, the gun went off, and a bullet went through Robert Varnardo’s neck: a wound that would kill him. The bullet then through Earthia B. Wiley’s arm, into his side and lodged in his back. Frenchy drove Lucky to Lyndale and Wayzata Blvd., then tossed the gun into the Mississippi River near Brooklyn Center.

How they caught Frenchy is a great story. Detective Inspective Charles Wetherille remembered that the dances were operated by a woman who rented the hall (probably Pat Black). From the description of the third man in the car, Black suspected a man she knew only as Frenchy. She did remember that Frenchy’s picture had been in the Minneapolis Star in a story about a “jive session” the previous September. Wetherille contacted the author and the photographer of the story, which turned out to be a review of a Ray Charles concert and dance. The photographer had taken a front shot of Frenchy dancing, but Frenchy asked him to “keep his mug out of the paper.” So the photo appeared with Frenchy’s partner facing the camera.

But the photographer still had the head-on photo on file, and voila! A photo of Frenchy’s face. Wetherille requested a dozen copies and distributed them to detectives. One got a tip, and at 3 am on July 6, Frenchy got rousted out of bed and brought to headquarters.

Once at the station, Frenchy admitted he had the gun, but swore it was unloaded, and that “someone grabbed it and it went off. I don’t know how the bullet got in there.” He was charged with first degree manslaughter, but on the day his case was to go to trial (September 9, 1957), he pled guilty to second degree manslaughter. On November 25, 1957, he was sentenced to a year in the workhouse and four years probation.

A bit more on Frenchy: he was born in 1931 in Milwaukee, and served as a paratrooper in Korea beginning in 1951. He was working as a telephone repairman at the time of the shooting, and was married. He loved to dance! During his jailhouse interview he admitted that he was a “real hot dancer” in the style known as “cool.” “I just go into a frenzy … and I don’t have to get drunk to get that way,” he said. He was temporarily reported missing during the 1965 Fridley tornado, but lived until 1983, when he died in Alaska. He is buried at Fort Snelling.

Here’s to Frenchy, the coolest dancer at the Labor Temple, 1957.

LOUIS JORDAN RETURNS

Louis Jordan brought his sextet to town on July 28, 1957. * It was a matinee dance, from 5:30 to 9:30 pm; travel requirements for a date in Seattle dictated the early time. This was his first appearance in the Twin Cities since he organized the small group, which featured Jackie Davis on electric organ, and Austin Powell on guitar. (Minneapolis Tribune, July 25 and 28, 1957)

1958

Percy Mayfield performed at the Labor Temple on July 3, 1958.

1958 – 1968

During this time it doesn’t appear that there were many, if any, musical events at the Labor Temple. Most of the articles that popped up were for Golden gloves boxing bouts.

1966

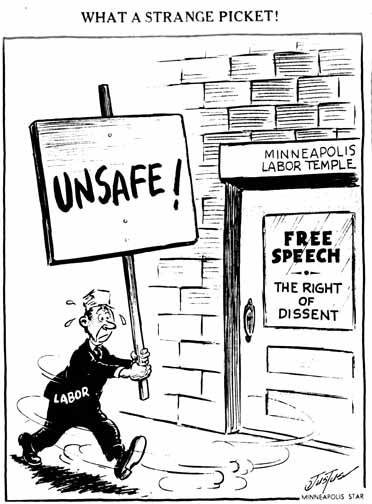

The Minnesota Committee to End the War in Viet Nam booked the Labor Temple for a rally for March 26, 1966. Scheduled to speak were Mulford Q. Sibley, professor at the U of M; Paul Krassner, editor of Realist magazine; Fred Stover, editor of U.S. Farm News; and Sidney Lens, a Chicago journalist.

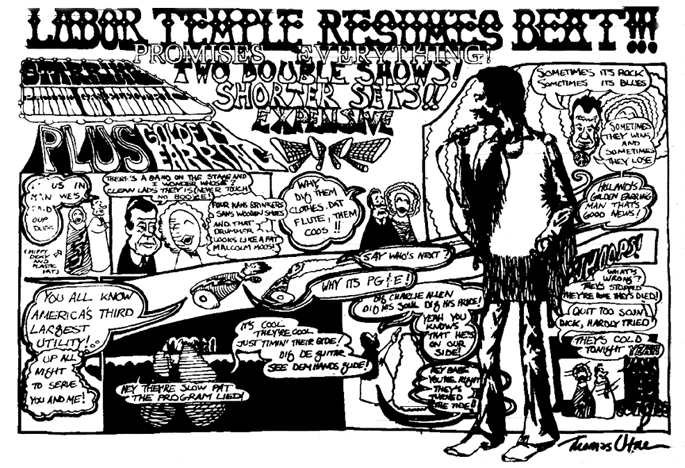

After a great deal of pushback from union members, many of whom had sons serving in Vietnam, the reservation was cancelled. Larry Seigle, Chairman of the Committee, was told that the Labor Temple was open to all groups, but not to “Communistic groups.” The rally was moved to the Unitarian Society, where a spokesman said they viewed the transaction as an “ordinary rental.” (Minneapolis Star, March 21, 1966) The political cartoon below appeared on the Star’s opinion page.

1967

PREACHER DIRECTS WRATH OF GOD AT LABOR TEMPLE

Another cancellation made waves, but in a different direction, in 1967. Rev. Dr. Carl McIntire was a controversial radio preacher from Collingswood, New Jersey. His “Twentieth Century Reformation Hour” was heard on 600 radio stations, and his message was fighting creeping Communism, which in his mind took the form of the War on Poverty programs and the “new morality.”

His reservation at the Labor Temple was cancelled, and he relocated to the Armory, where he drew about 500 people on May 5, 1967. There, he accused Minneapolis of being soft on Communism. “Somebody tells me Minneapolis sent a trade delegation to Moscow. What’s wrong with you people?” And, “What this country needs is not more political and social action and socialism.” (Minneapolis Star, May 6, 1967)

THE HIPPIE ERA

After a considerable lull, music reappeared at the Labor Temple, this time with a completely different cast of characters. Although a lot of the music that the young people of the 1960s were listening to was based on American Rhythm & Blues, one wonders whether they knew of the amazing artists who had performed under the same roof in the ’40s and ’50s.

FILLING A NEED

The closest venue to compare to the Labor Temple was Dania Hall on the West Bank, where concerts and dances had been held for several years. But few of these were advertised, so it’s difficult to document when they were or which bands were featured. In general they were probably not regularly scheduled, and usually featured favorite local groups, especially the Paisleys. Dania Hall was a much smaller venue, and the search was on for a place where bigger groups and larger audiences could be accommodated.

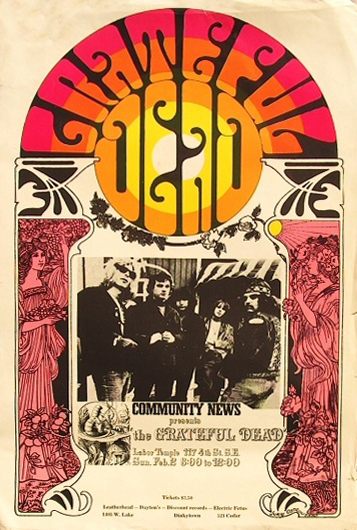

COMMUNITY NEWS

The first set of concerts were “Presented by Community News,” a group headed by Charlie Campbell. After graduating from White Bear Lake High School in 1965, Charlie traveled to California where he “interned” with a group called the Magic Theater, an offshoot of the Merry Pranksters. There he learned the psychedelic light show trade.

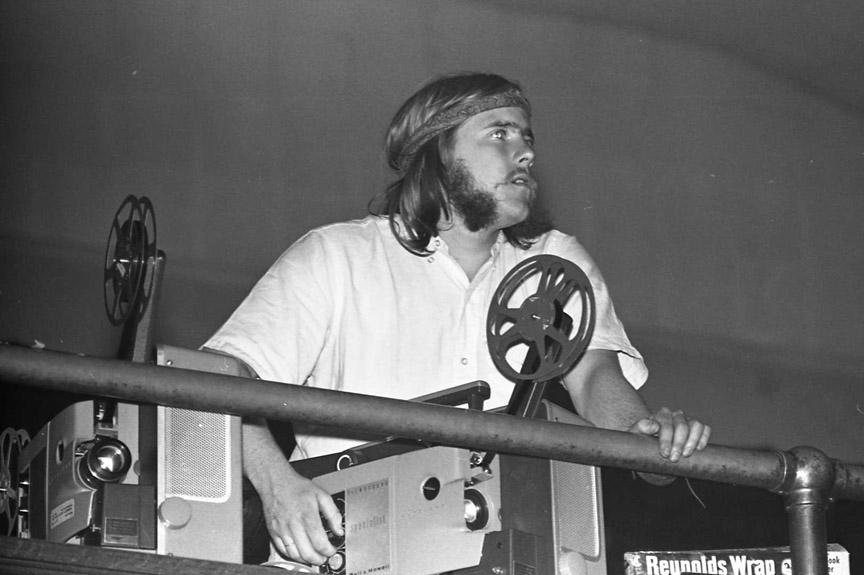

He returned to Minnesota and started a light show group, Community News, with his brother and two others. One manned an overhead projector, one a slide projector, one did the requisite liquid light show with vegetable oil and food coloring (the trick is in the concave clock face), and Charlie had the movie projector. He would check the movies out of the public library – some art films mixed with some Busby Berkley and cartoons.

Charlie:

Our first gig was with the High Spirits at Coffman Memorial Union at the U of M, on May 19, 1967. After realizing that the bands at the time didn’t see the value of splitting their fee with a light show group, I concluded that we needed to put on our own shows and hire the band. We started our run at Dania Hall on the West Bank, which was perfect, in the fall of ’67. The bands we worked with were Noah’s Ark, TBI (True Blues Incorporated), Pandemonium Side Show, Mill City Blues Band, Jokers Wild, and the Litter among others. The Paisleys, with a competing light show, played every other week. It was after a Jokers Wild show there in December ’68 that their manager, Dave Anthony, lamented that there wasn’t a bigger venue to handle the crowds (we were over capacity at Dania) that we revealed our discovery of the Labor Temple.

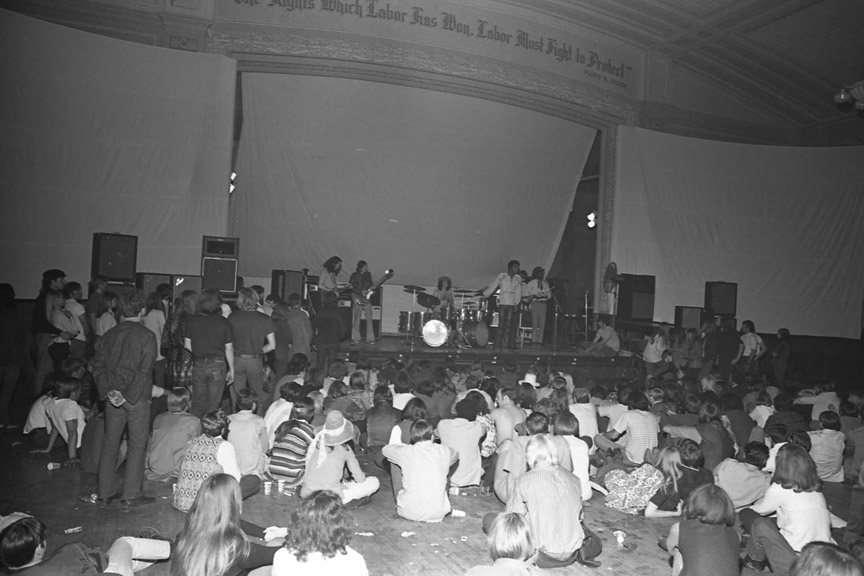

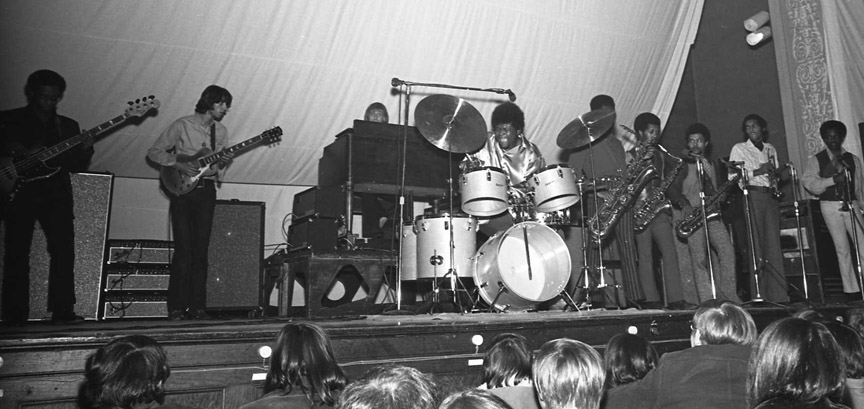

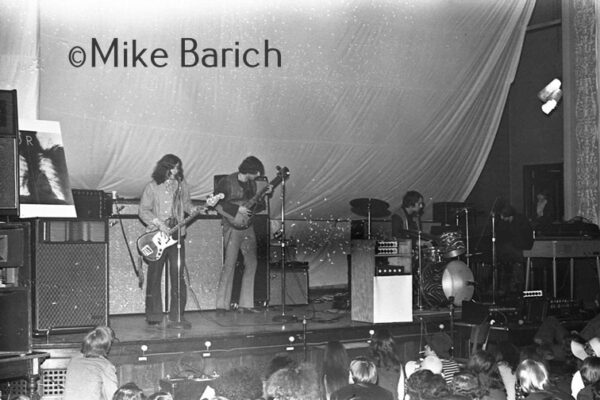

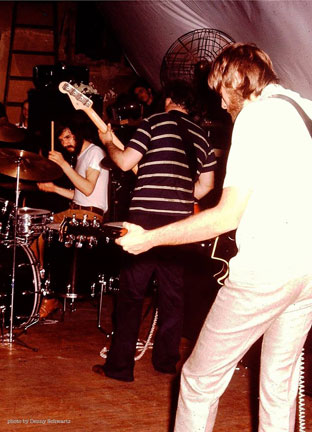

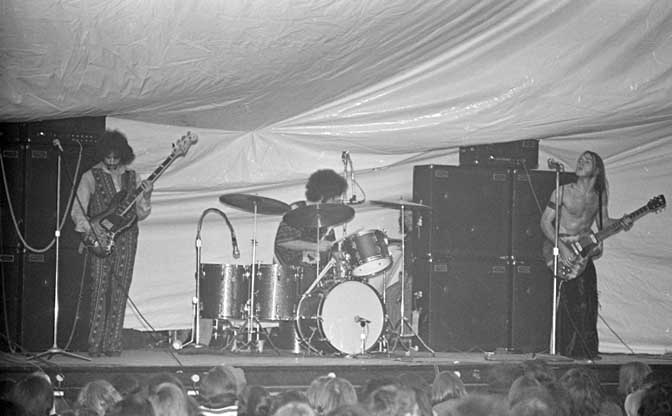

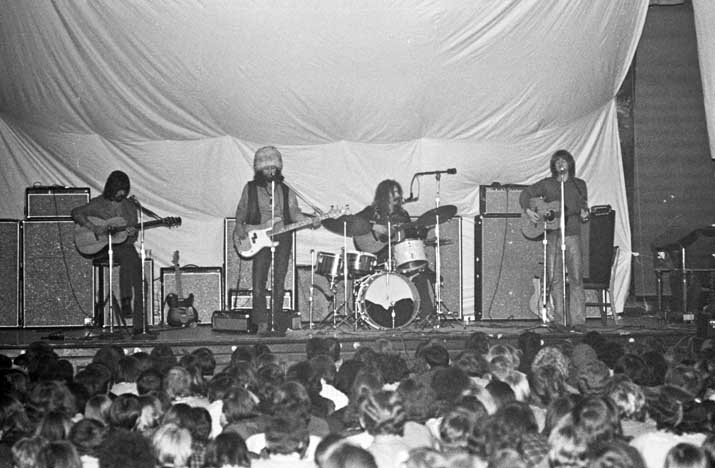

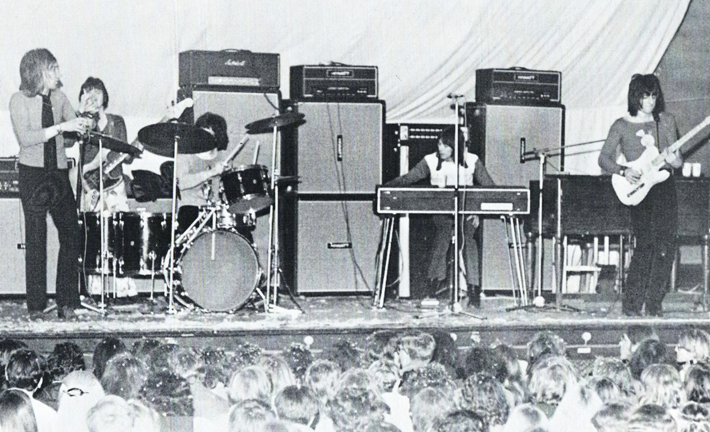

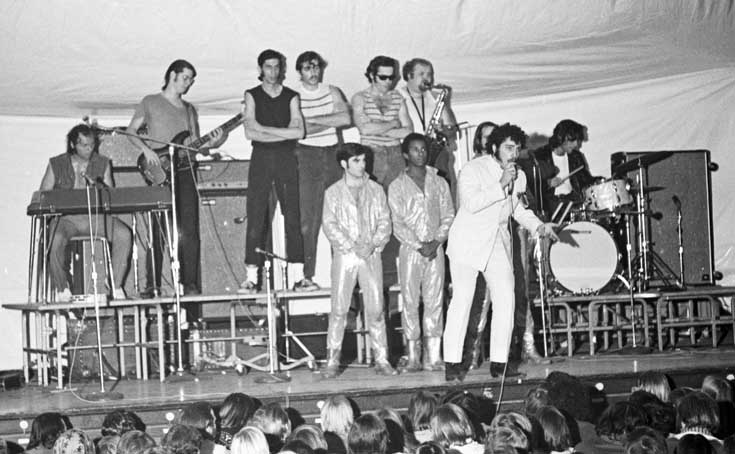

The photo below (from the Spirit show) gives a balcony-eye view of the scene below.

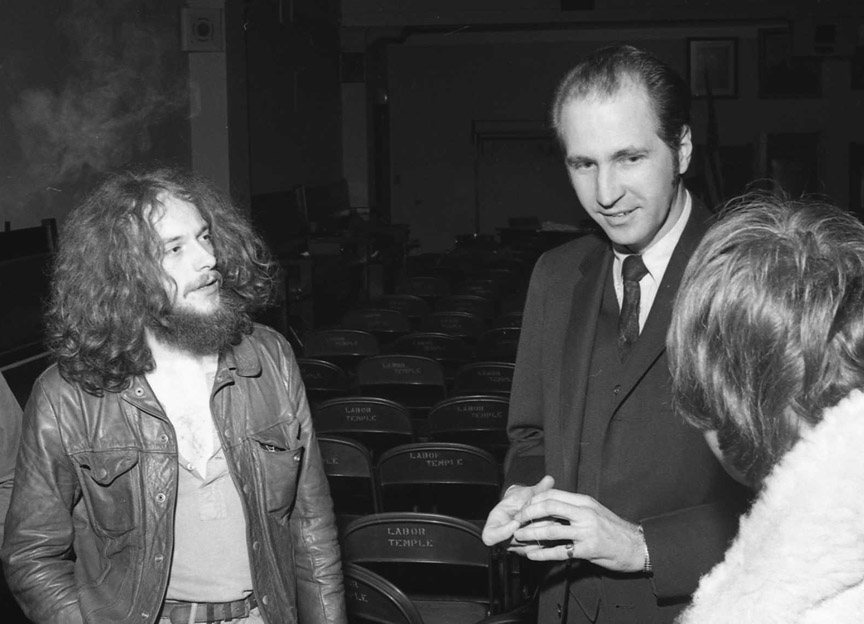

DAVID ANTHONY

David Anthony was a major music promoter and agent in the ’60s. The owners of the Labor Temple wouldn’t rent to a long-haired hippie freak like Charlie, but they would do business with David, so David hired Community News to do the light shows and handle the tickets and posters. In 1969 he started booking national psychedelic acts, some of which were not all that well known yet and couldn’t fill one of the bigger halls. Anthony was easy to find at shows, as he was the only one in a three-piece suit!

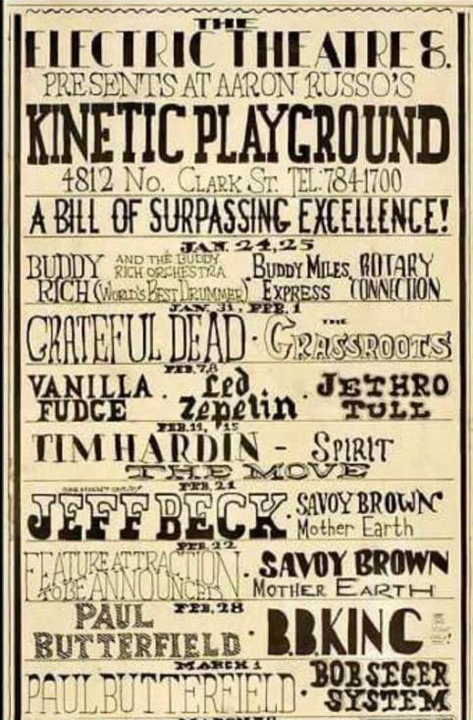

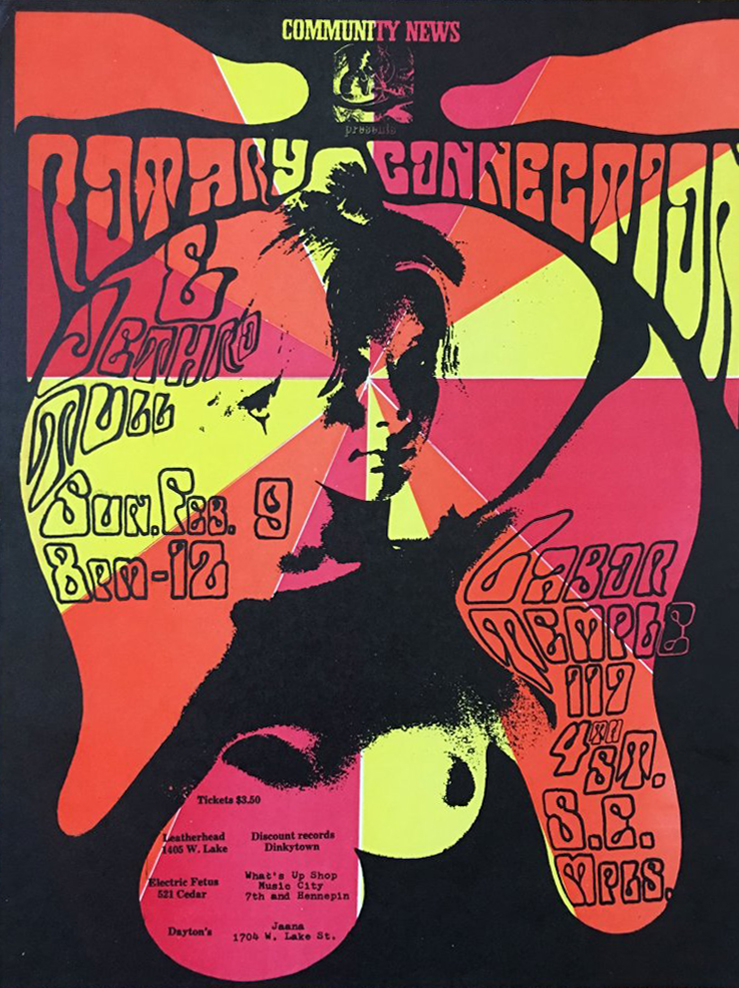

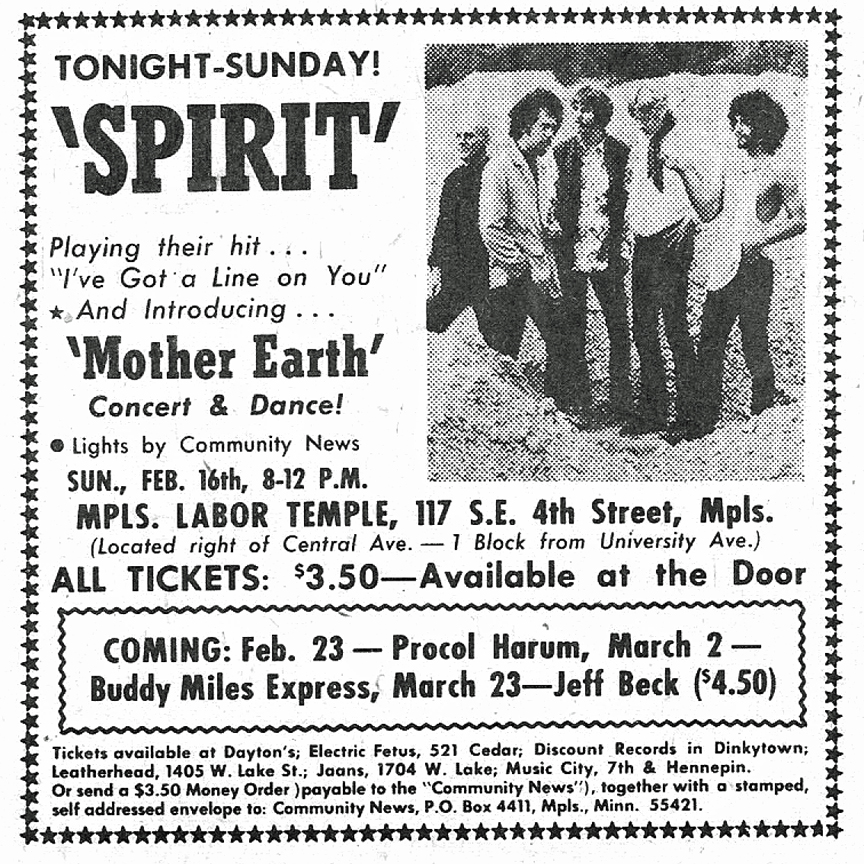

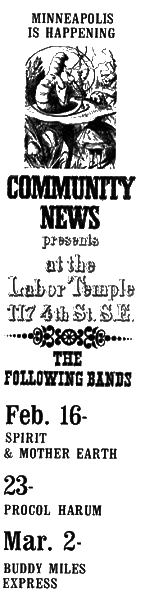

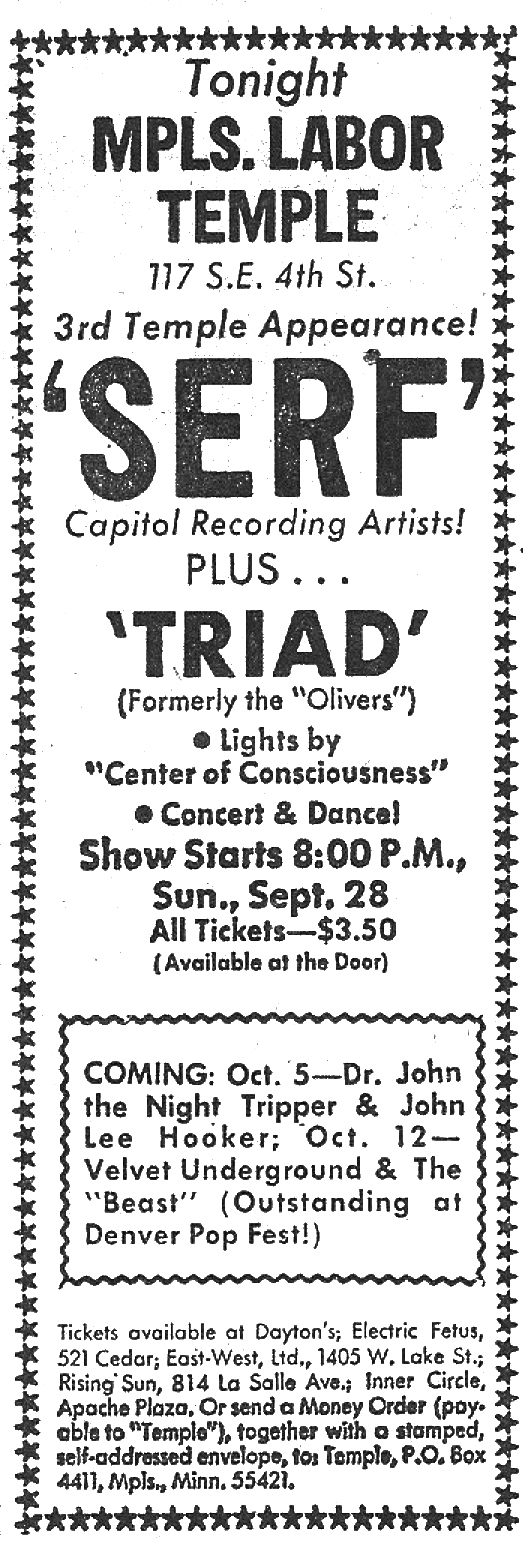

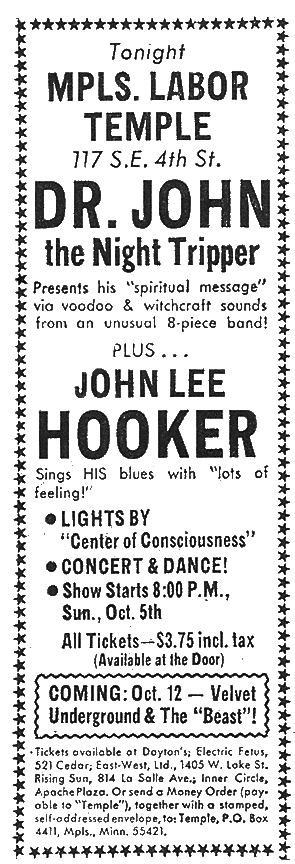

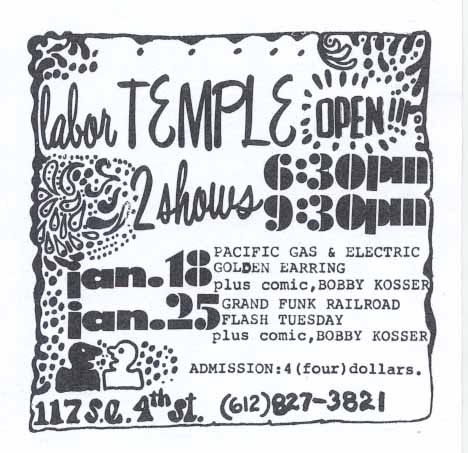

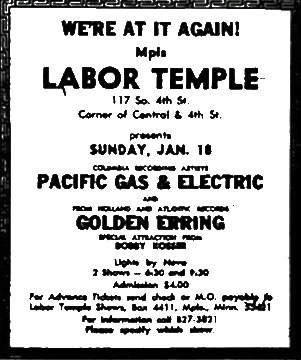

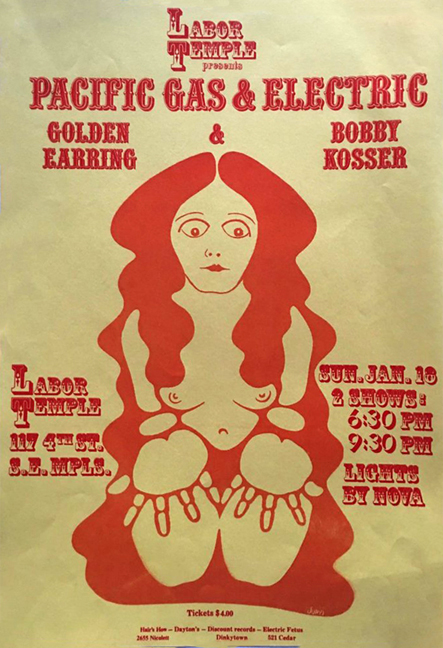

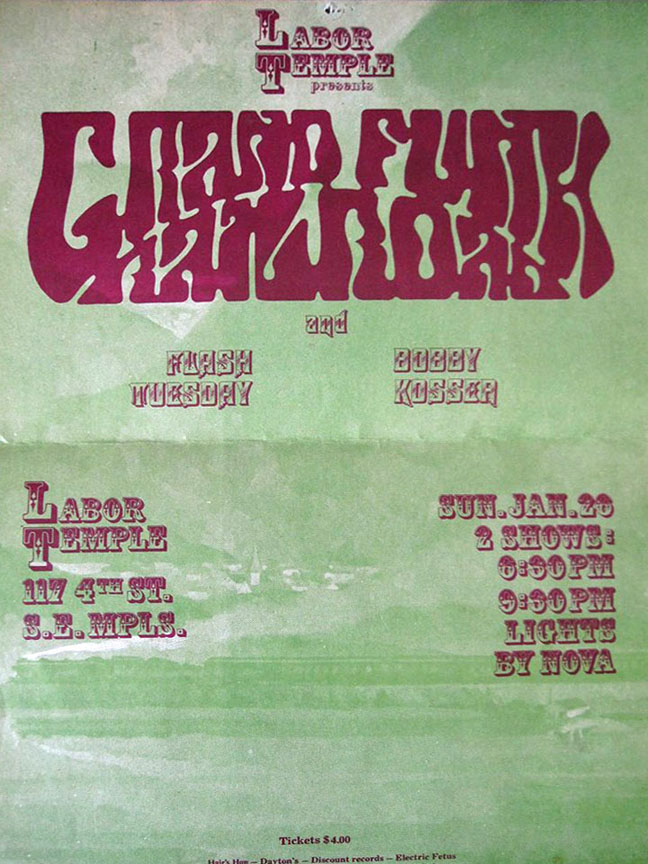

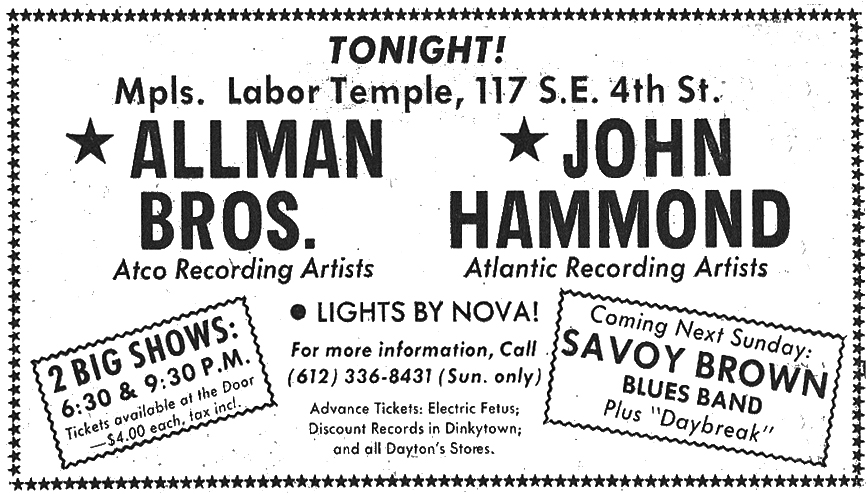

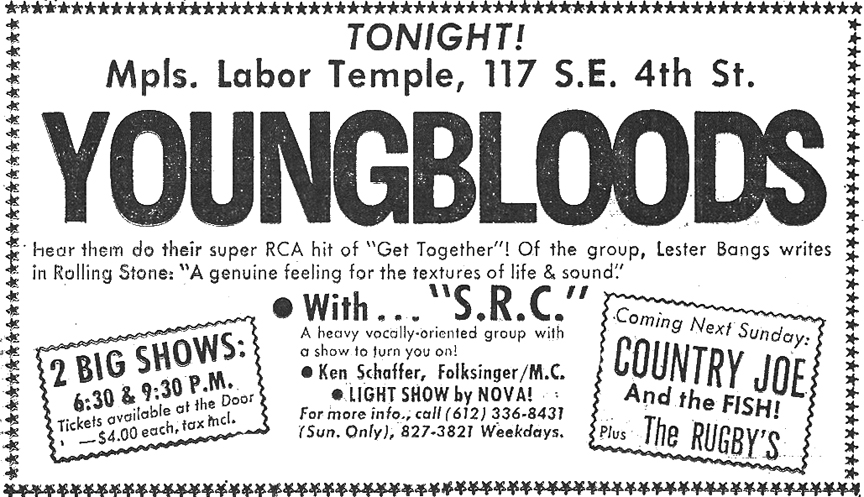

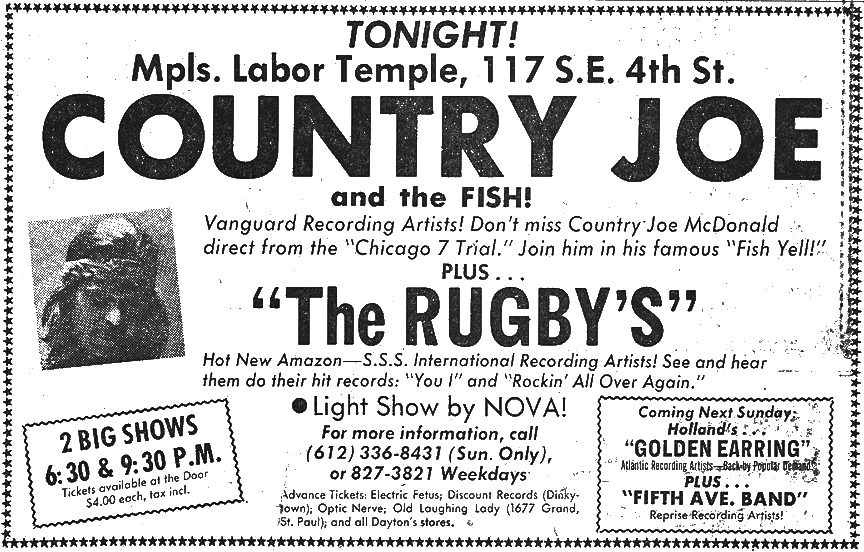

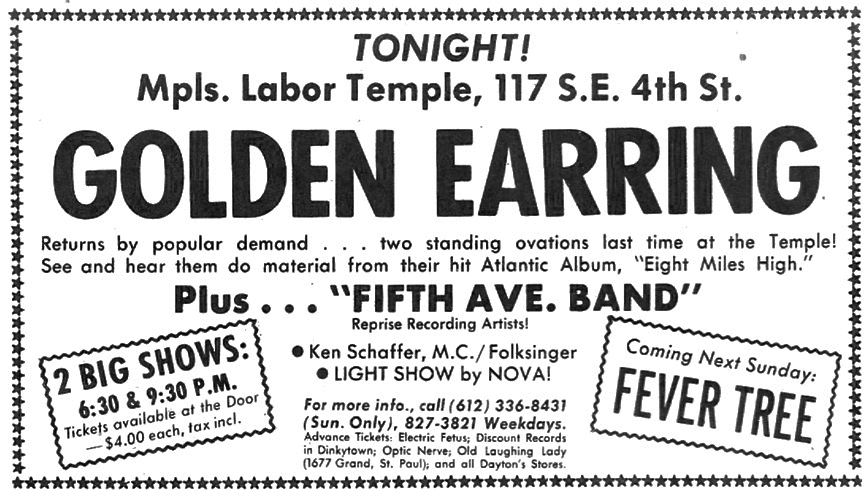

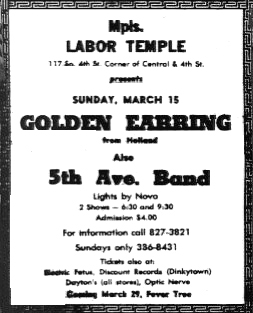

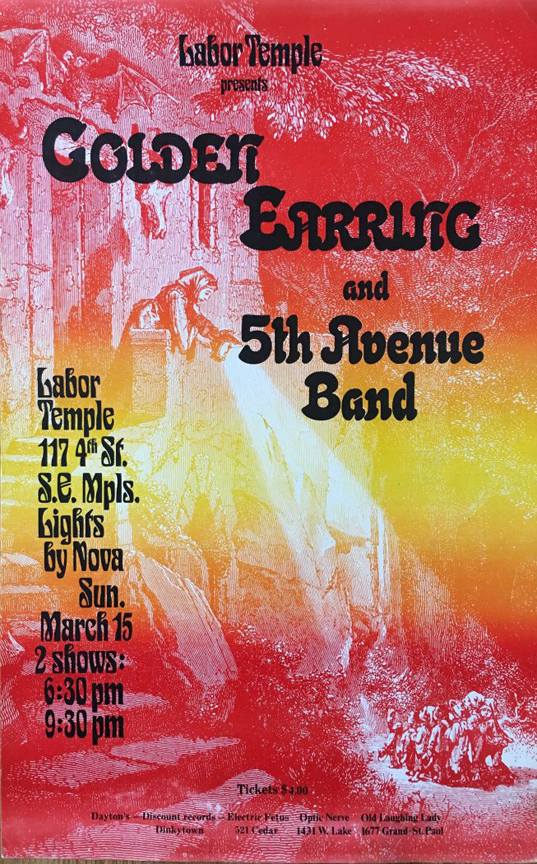

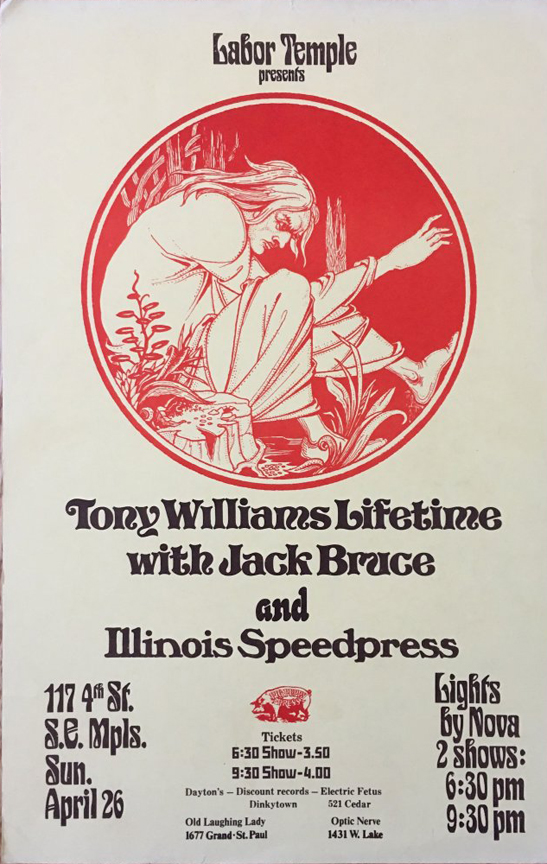

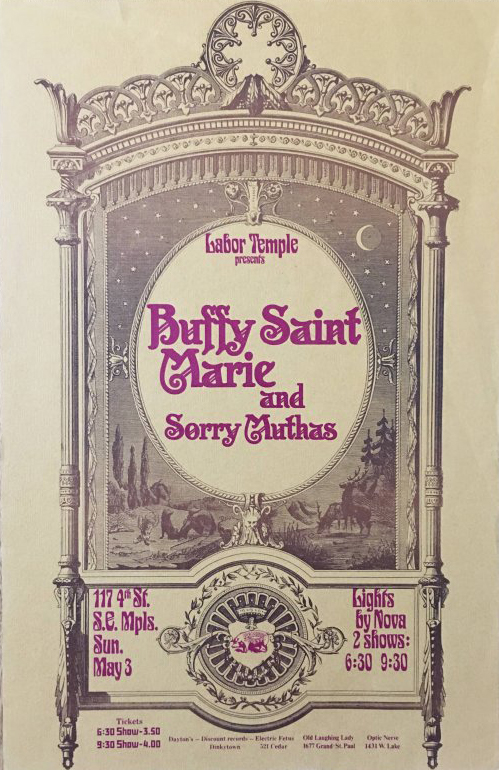

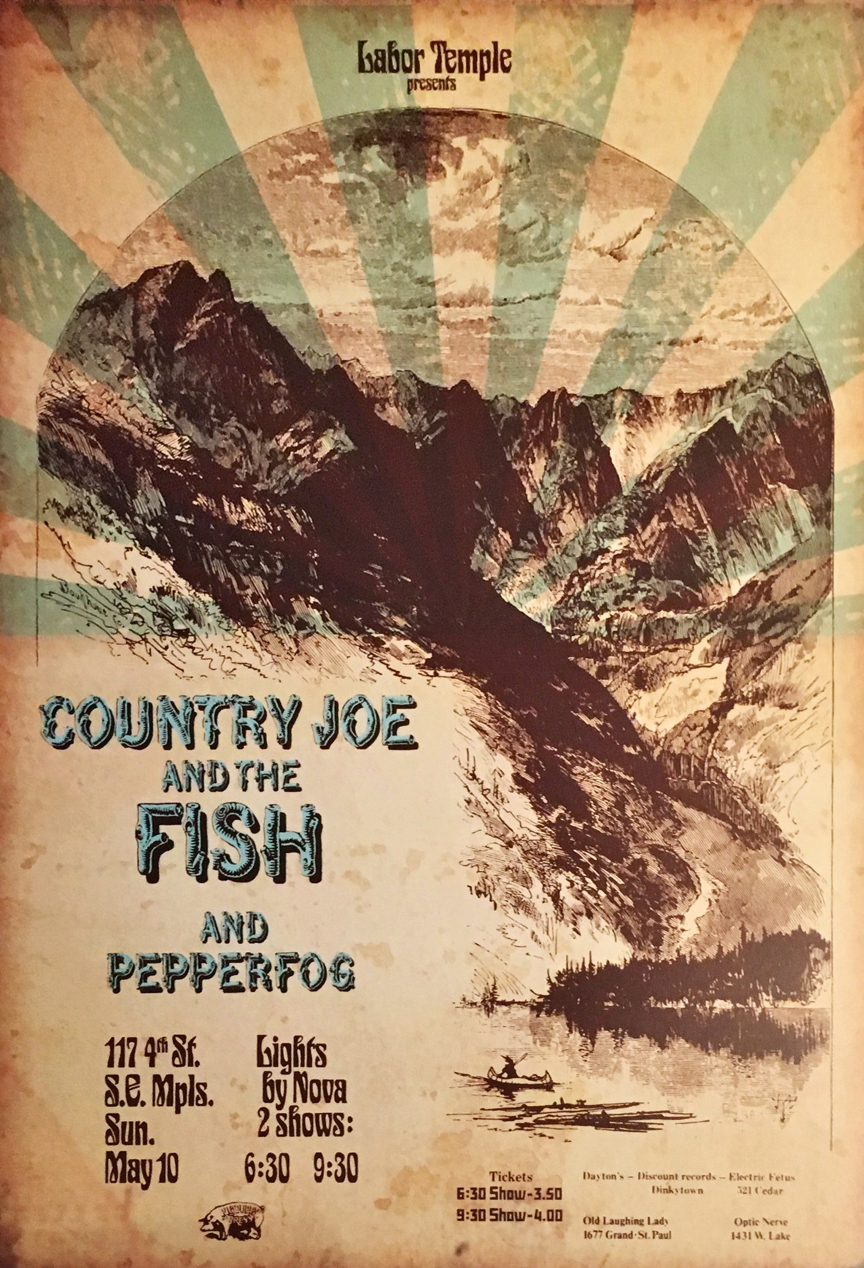

The very first Labor Temple Concerts in 1969 were only affordable because David Anthony was able to get the groups in to town on Sundays after playing weekends in Chicago at Russo’s Kinetic Playground. On the poster below, notice the dates of the weekend performers and compare them to the Sunday night show at the Labor Temple:

Grateful Dead:

Jan 31-Feb 1 Russo’s Kinetic Playground

Feb 2 Labor Temple

Jethro Tull:

Feb 7-8: Russo’s Kinetic Playground

Feb 9: Labor Temple

Spirit:

Feb 19: Russo’s Kinetic Playground

Feb 16: Labor Temple

Mother Earth:

Feb 22: Russo’s Kinetic Playground

Feb 16: Labor Temple

Anthony said he paid between $2,000 and $5,000 for an act, and priced tickets accordingly. Unfortunately, all of Anthony’s archives were destroyed – imagine what he might have had!

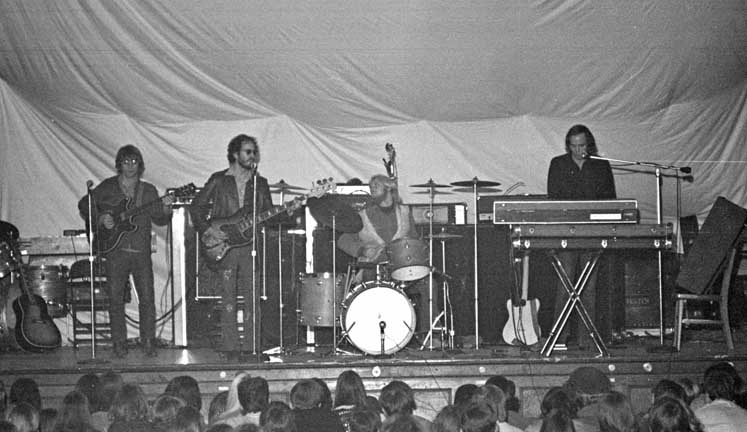

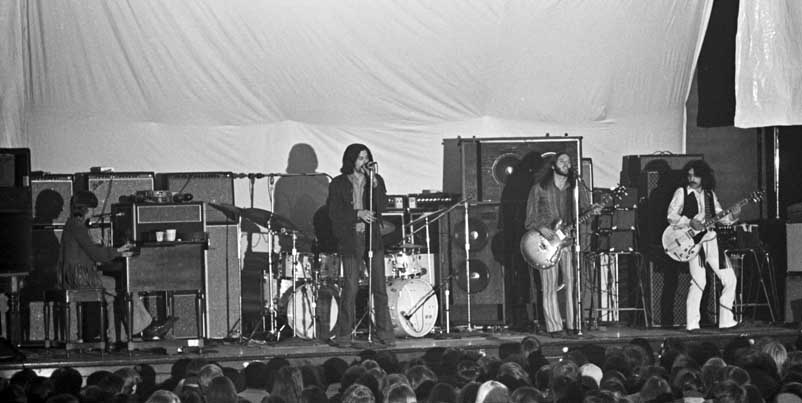

Labor Temple shows were held almost every Sunday night during its run, except during the hot summers). It was stressed in most reviews that this was the first venue in Minneapolis where there were regularly-scheduled rock concerts – something that had been sorely needed. Many compared the venue to San Francisco’s Fillmore West in that regard.

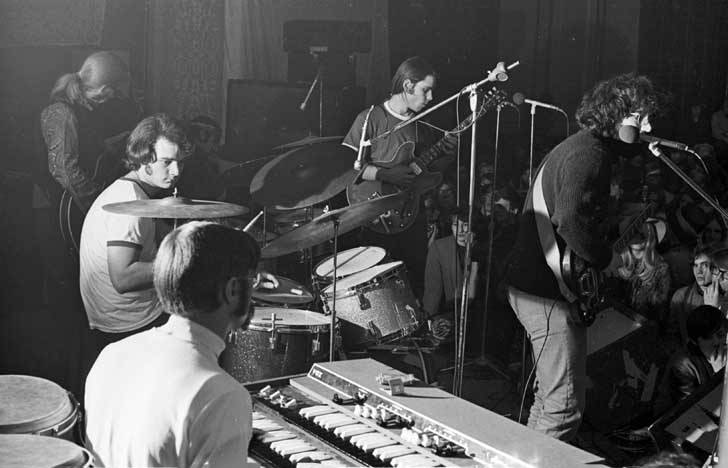

GENERAL NOTES:

- Concerts were on the third floor of the hall. Hauling those Hammond B3s up those marble stairs was a bitch.

- Above the stage was inscribed the quote, “ “Those rights which Labor has won, Labor must fight to Protect.”

- The Manager of the Labor Temple was John Bruchard.

- Anthony hired five off-duty police officers, who generally had nothing to do; one article characterized concert-goers as “lovers, not fighters.”

- The main floor had chairs along the sides; the middle was open for sitting, standing, dancing, enjoying the music.

- The balcony had chairs.

- The capacity was 1,250.

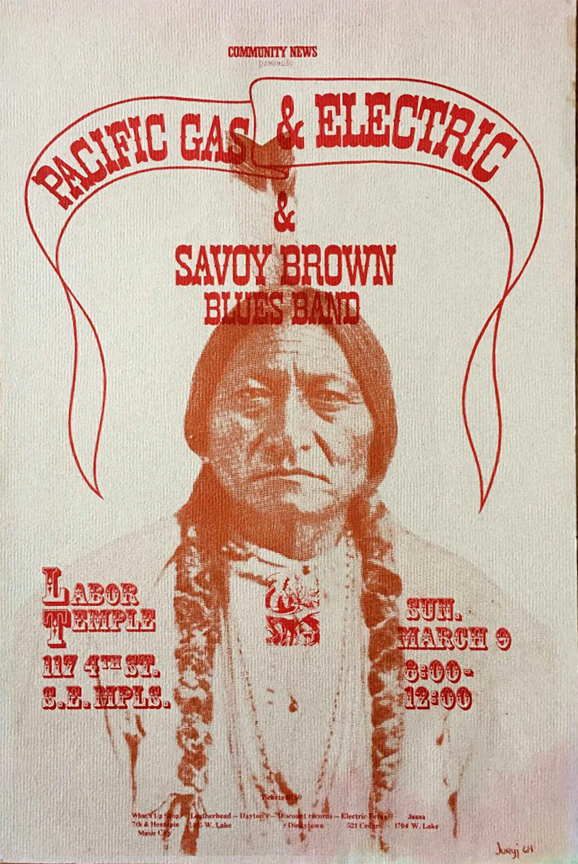

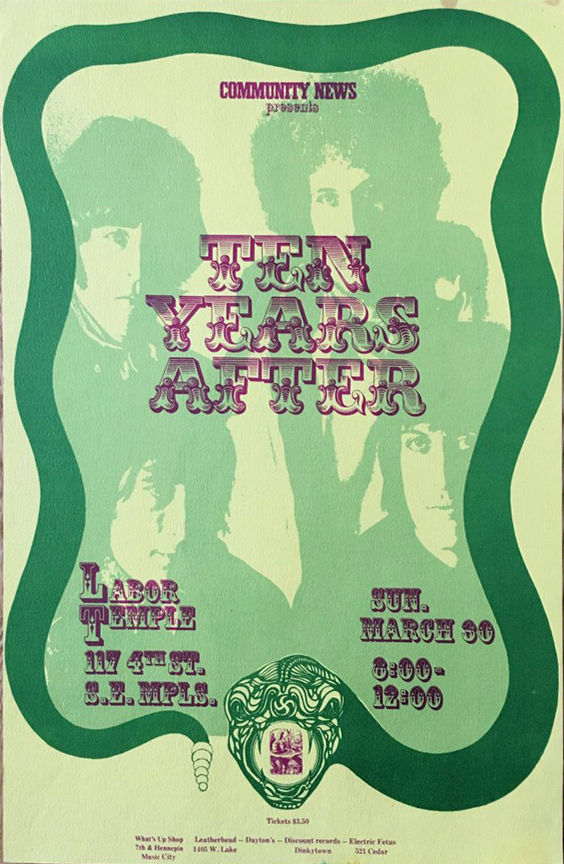

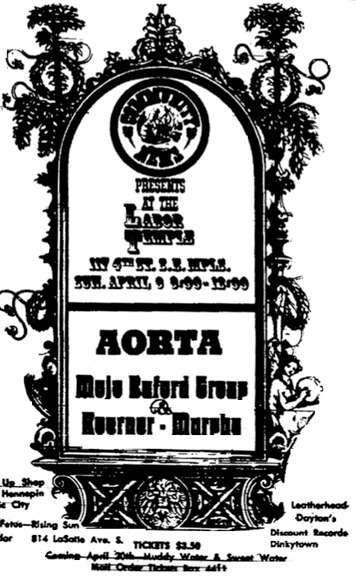

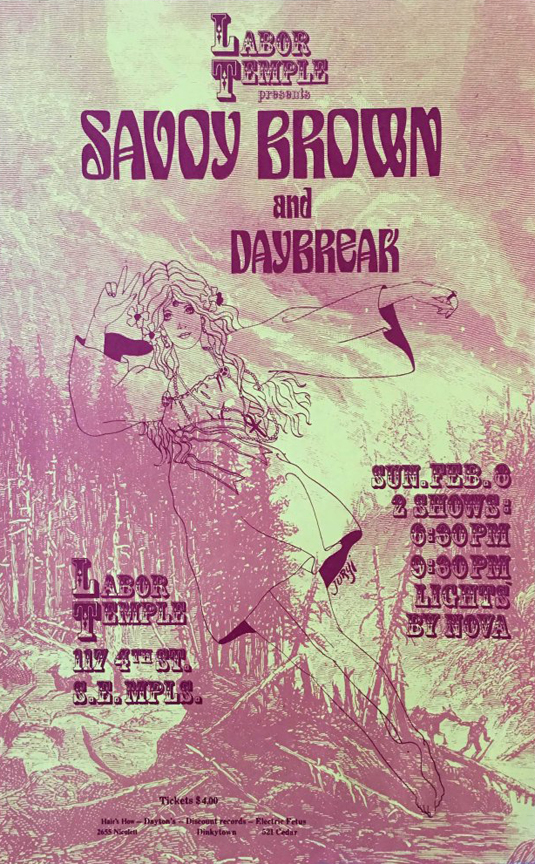

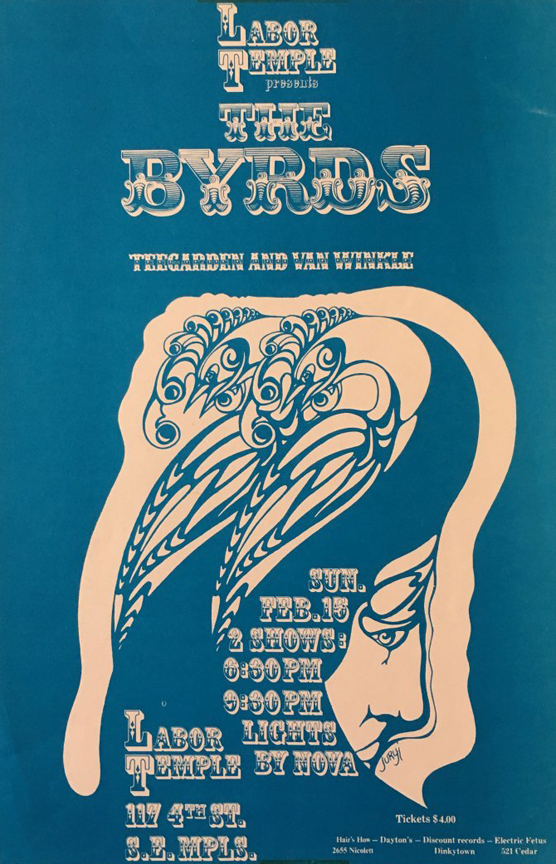

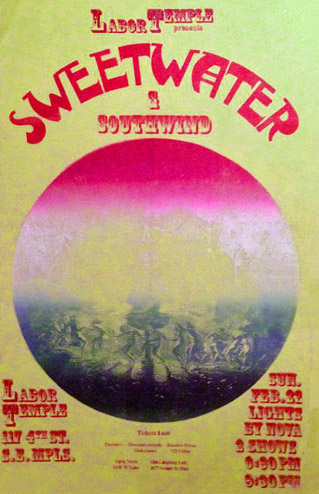

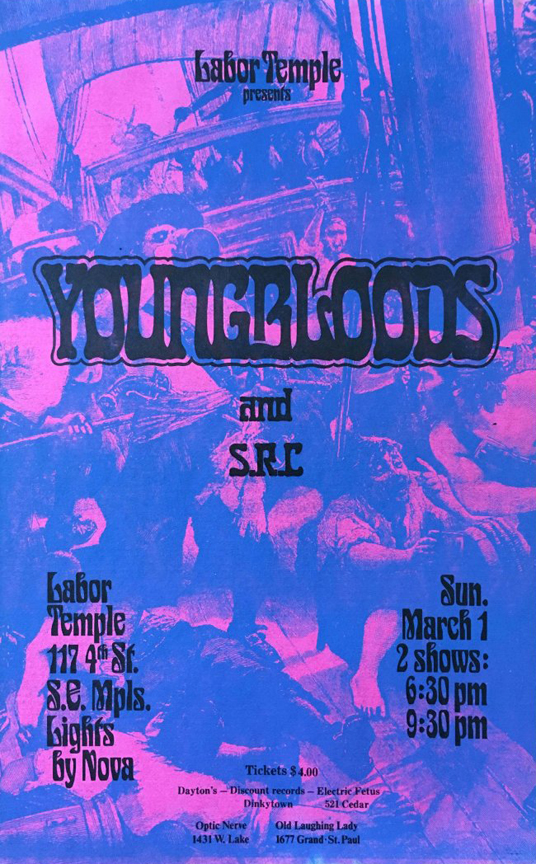

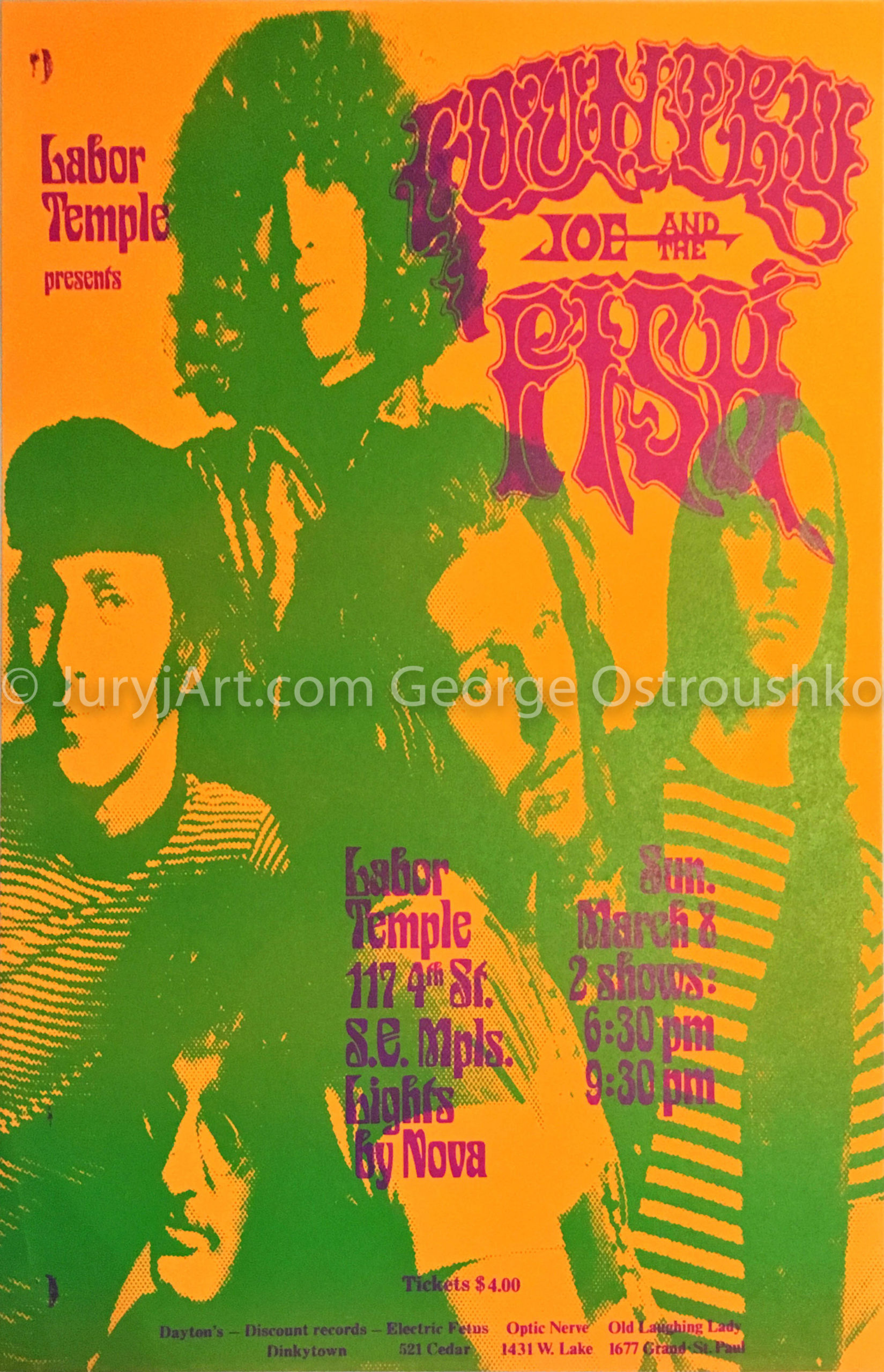

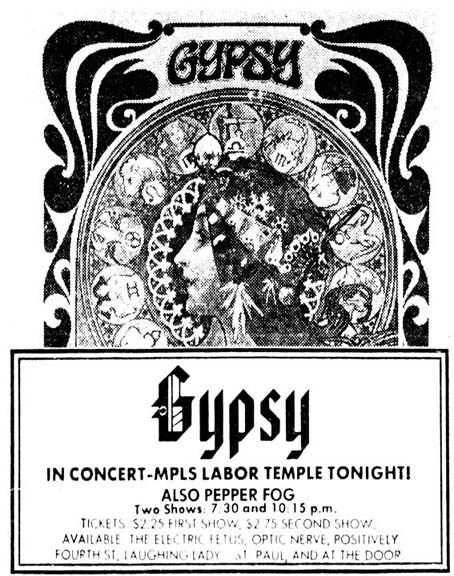

- Posters were created by Juryj (“George”) Ostroushko. Many images can be found on his website.

-

Other poster images are courtesy of poster collector and auctioneer Paul Pash.

- Most of the Minneapolis Star and Tribune ads below are courtesy of Mike Jann.

- Robb Henry had the foresight to capture ads from the Minnesota Daily while it was online; it has disappeared since. I deeply appreciate Robb’s sharing his scans with me to post. See a collage on Robb Henry’s blog.

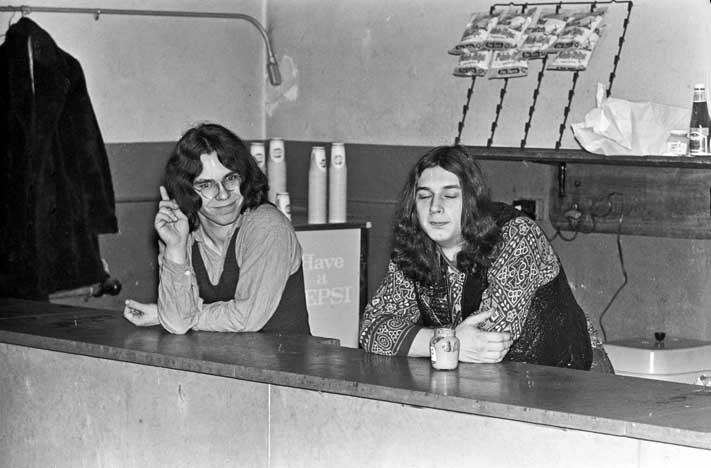

CONCESSIONS

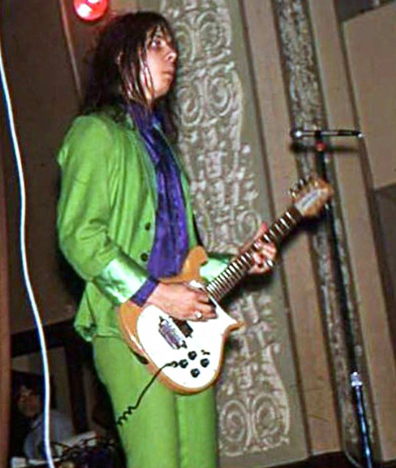

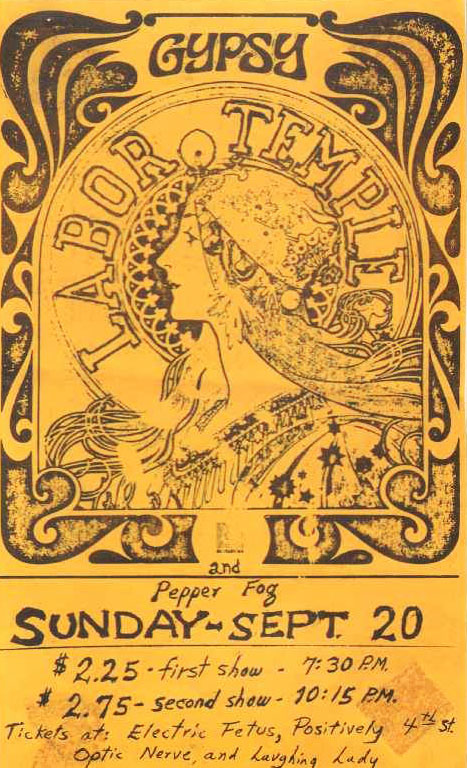

The concession stand was often manned by Gregg Inhofer and Bobby Strength of Pepper Fog (below). An unusual offering was tangerines for 25 cents. No alcohol was sold.

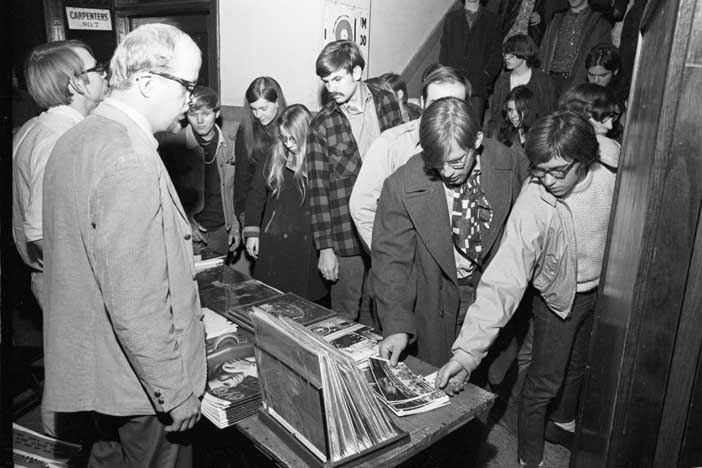

Discount Records sold LPs in the building at some shows. The photo below is from the Spirit show.

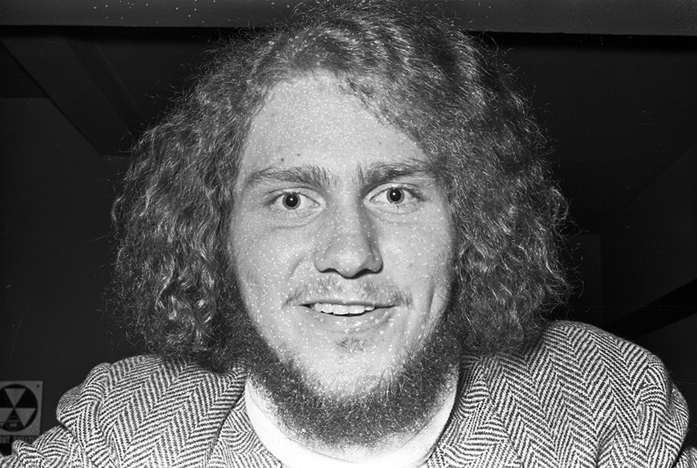

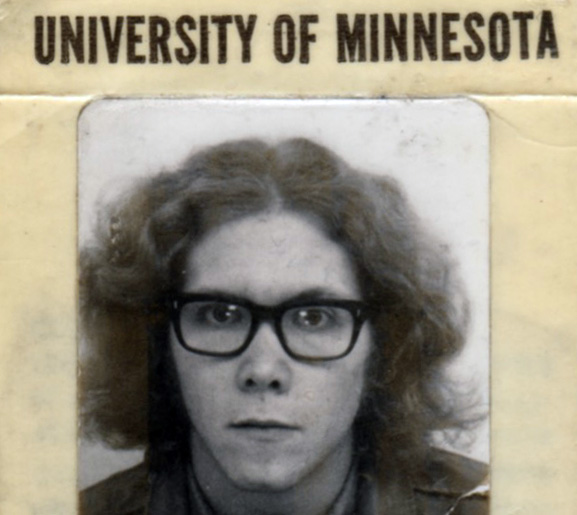

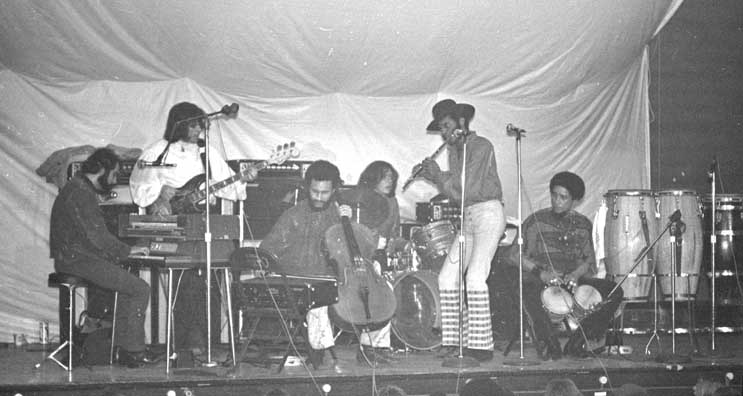

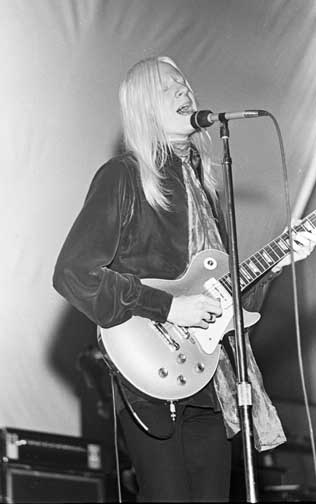

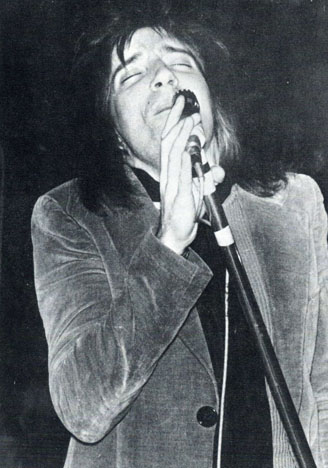

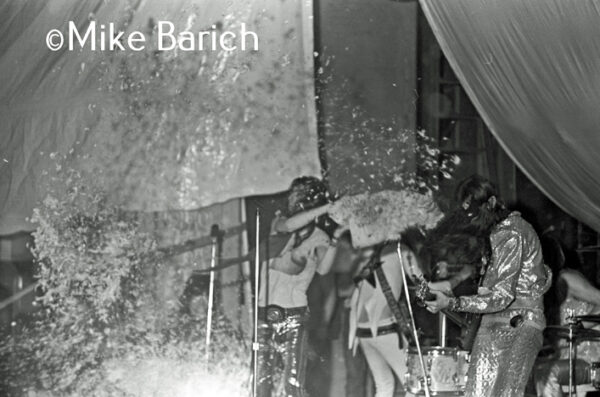

MIKE BARICH

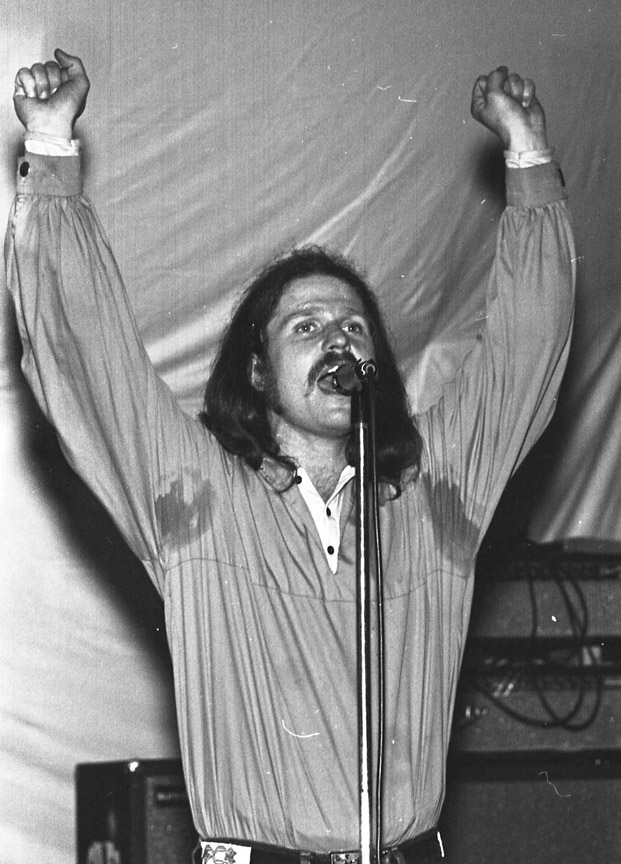

Most of the photographs you see here were taken by Mike Barich, the staff photographer for Connie’s Insider magazine. In 2019 into 2020 (and ongoing), David Roth of tpt has been scanning Mike’s negatives, most of which have been stored in Mike’s basement for 50 years. Mike has generously allowed me to post them, for which I thank him profusely. I have not watermarked them, as watermarks can be removed, but I only post all of my photos at 72 dpi – a low enough resolution so that they can’t be grabbed and sold. We owe Mike a huge debt of gratitude for taking these photos and preserving the negatives over the years. And a huge thank you to David for taking on the gargantuan task of scanning these thousands of negatives, starting with the Depot for his documentary on the 50th Anniversary of First Avenue in April 2020, and then the Labor Temple, my favorite venue!

MARSHALL FINE

Many of the reviews you will see here were written by Marshall Fine while he was a theater student at the University of Minnesota; his reviews were published in the Minneapolis Star. Fine honed his journalism skills at St. Louis Park High School (my alma mater!), working on the school paper, the Echo. His career skyrocketed, bringing him to New York City as a major film critic. Highlights of his impressive resume can be seen on the St. Louis Park Historical Society website.

THE FIRST PRESS

CONNIE’S INSIDER

As usual, Connie Hechter, publisher of Connie’s Insider, was Johnny-on-the-Spot, reporting on the new venue in the January 25-February 1, 1969, issue of his music magazine.

TEMPLE TO FEATURE TOP UNDERGROUND ACTS was the big headline of the issue. David Anthony was quoted: “We will concentrate on booking the top underground talent in the country, and we hope to eventually open on Friday and Saturday nights too, using local-regional talent as well as national acts.”

MINNEAPOLIS TRIBUNE, January 26, 1969

Entertainment columnist Mike Steele:

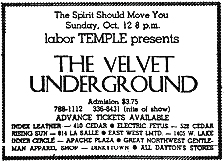

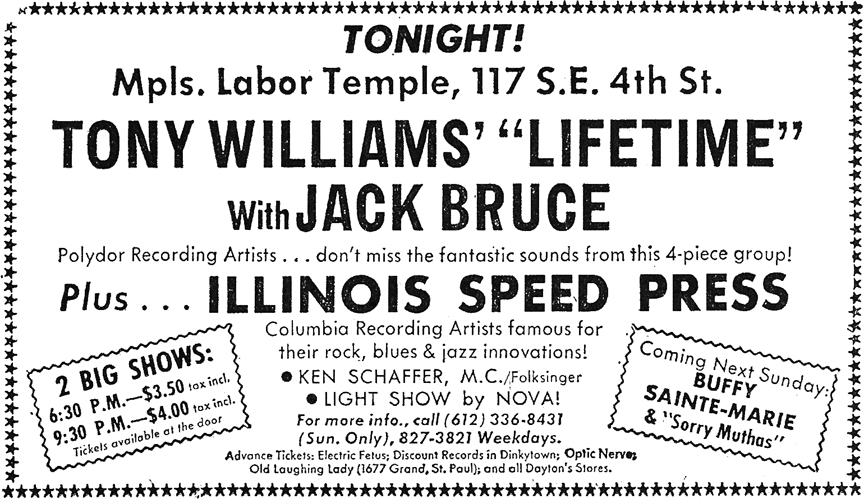

Another attempt at a Twin Cities underground rock – blues ballroom will open Feb. 2 in the Minneapolis Labor Temple, 117 SE 4th St. David Anthony, a local booker of pop music groups, will do the booking for the producers of the hall, Community News, former producers of Dania Hall concerts. It will be called The Temple and open with Sunday concerts only, running from 8 pm to midnight. The Grateful Dead will play the opener, followed Feb. 9 by The Rotary Connection and Jethro Tull. Others on the schedule are The Spirit, Jeff Beck, Ten Years After and the Who. Tickets are $3.50.

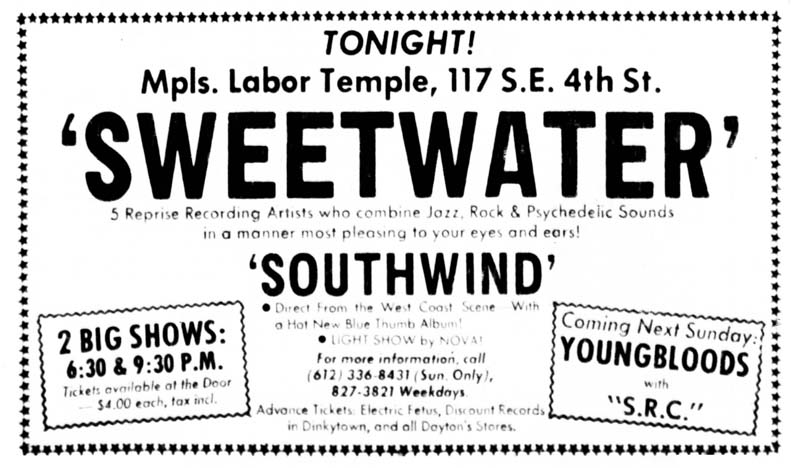

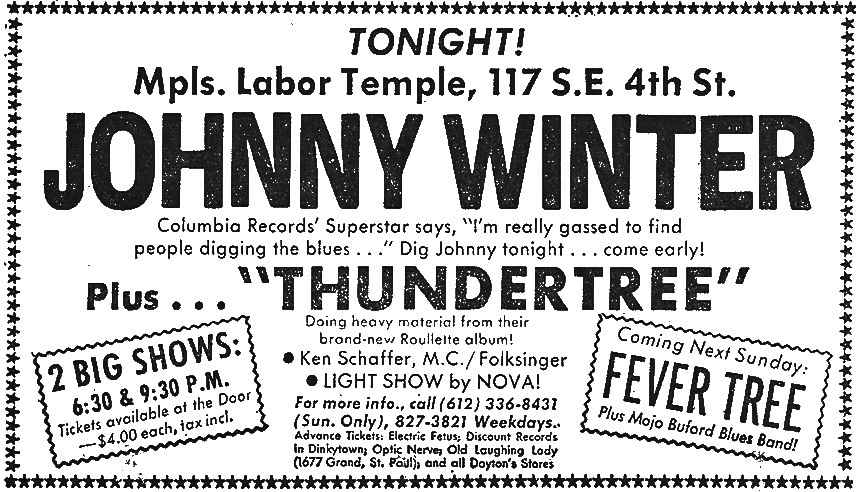

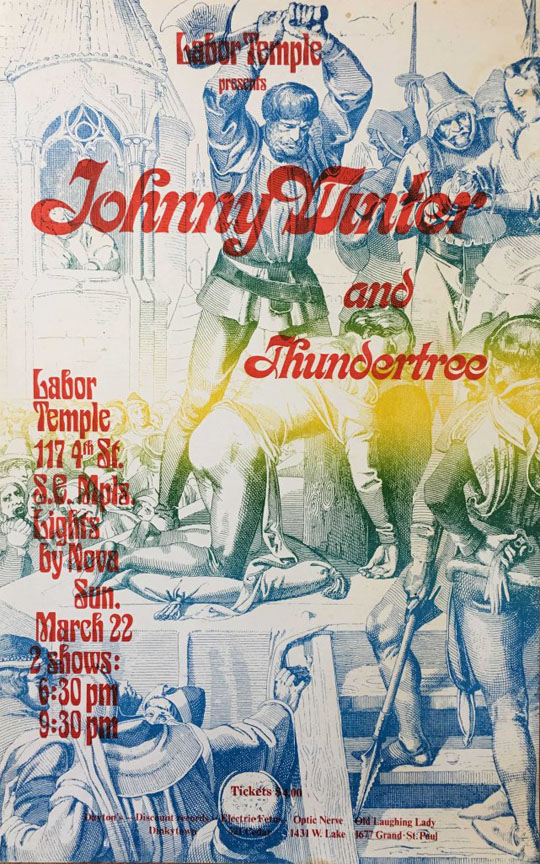

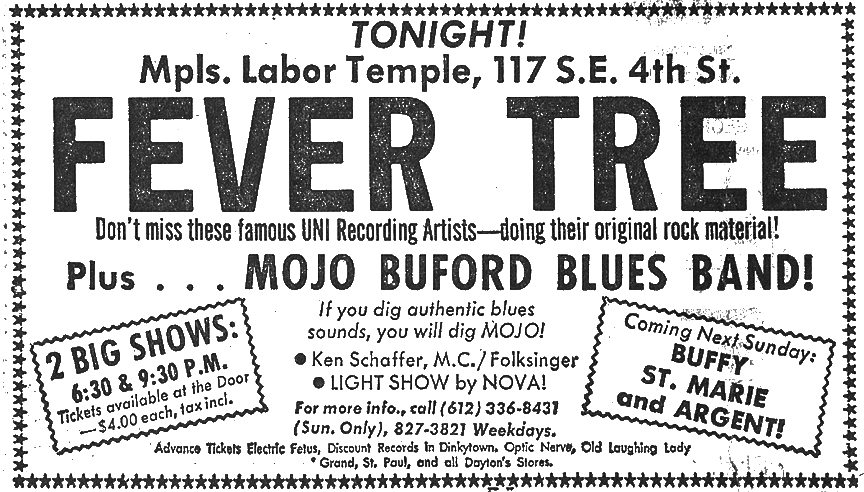

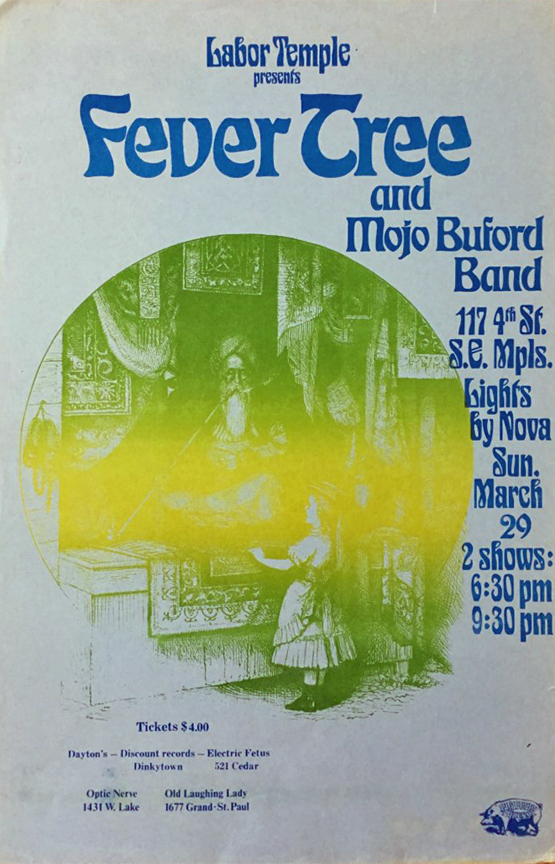

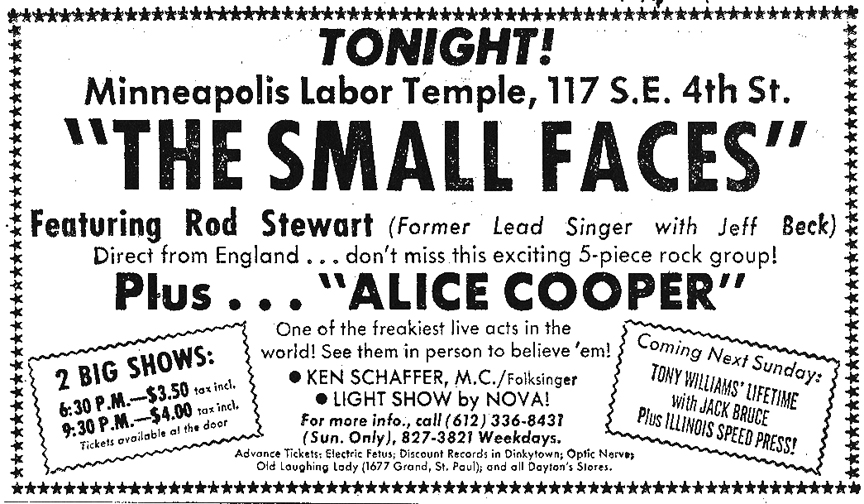

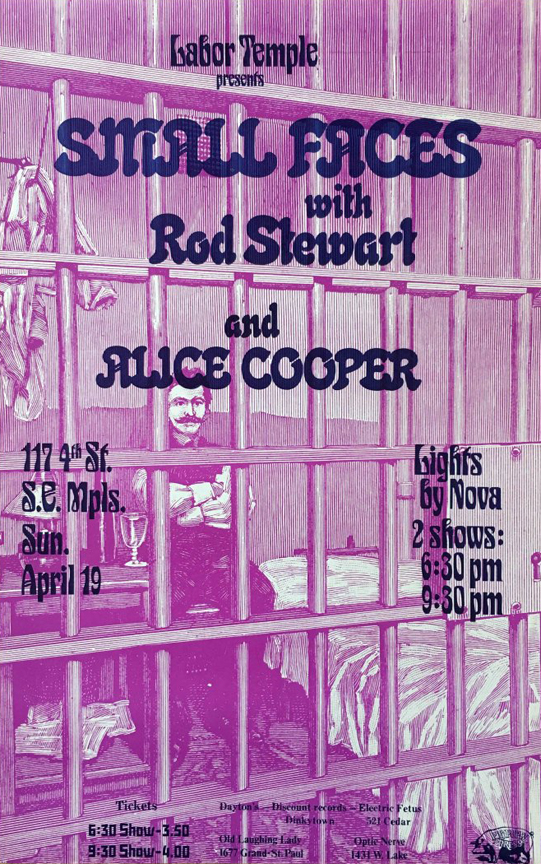

SHOWS AT THE LABOR TEMPLE: 1969 – 1970

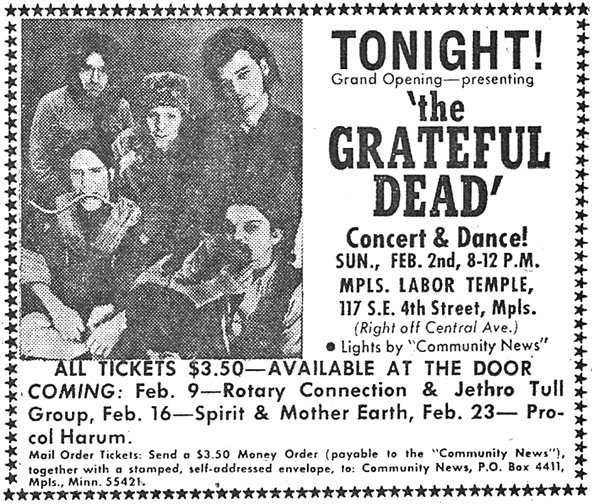

GRATEFUL DEAD AND BLACKWOOD APOLOGY – February 2, 1969

Allan Holbert wrote a column of the impending opening concert at the Temple on February 2, 1969. “Big time rock action begins for the first time in Minneapolis on a regular basis with a combination concert and dance (or whatever you want to do).”

He described the groups to be presented at the Temple as “either nationally known underground rock groups or groups that are just starting to break into the big time.” He reported that David Anthony was to be president of Community News when it became a corporation. (Minneapolis Tribune, February 2, 1969)

Anthony was quoted as such:

We’ll have the Community News light show and people will just come in and mostly sit on the floor in little groups and groove with the music. What we want to achieve is an intimacy you just can’t get in a big hall like the Minneapolis Auditorium or the Armory.

The atmosphere’s just wrong in those big places. There’s the act and there you are and there’s no real good relationship between the audience and the act.

The Dead arrived with an iguana, a rooster, goat, snake, and three kids. Although it was 25 below zero and tickets were an onerous $3.50, the people came.

MINNEAPOLIS TRIBUNE (no byline), February 3, 1969

GRATEFUL DEAD SOCK IT TO 2,000 MUSIC LOVERS

The Labor Temple was packed. The audience, mostly late-high-school and college-age youth, completely filled the chairless main floor, sitting or standing. And all other seats and aisles were taken in the balcony.

As a preliminary to the Grateful Dead, a local group called the Blackwood Apology held forth for an hour or so with the same sort of electric sound. It came on like just what it was: hundreds of watts of electrified musical power pounding out of great stacks and racks of amplifiers.

And above, lights flashed multicolored, changing images of psychedelia on great wide screens. Making it happen was the Grateful Dead, a group billed as the leader of underground rock, as the nationally famed but uncompromised original.

The more than 2,000 young people who jammed the Minneapolis Labor Temple to hear them Sunday night took it quite coolly. They liked it, they clapped a lot, and some of them danced. But mainly, they did what you do with this kind of youth art: They experienced it.

After a long delay for setting up their nearly 100 pieces of equipment, the Grateful Dead came on with a sound like the end of a bad trip. It was a horrendously penetrating hum from an amplifier gone mad. But when they got the amplifier squared away, they showed that they can play as well as make noise. Using some incredibly complex tempos and fine improvisations, they did the mixture of jazz and rock and folk that – along with the lights and, in some cases, marijuana – has been turning on people around the country for several years.

MINNEAPOLIS STAR, February 3, 1969

Johan N. Mathiesen was identified as a Minneapolis writer and critic. For sure he was a fan of the Grateful Dead! Jerry Garcia’s guitar was “deft and lyrical.” Phil Lesch’s bass was “wandering, penetrating.” “Add to that the complex beats of two excellent drummers and you have the finest rhythm section in all of rock and probably beyond.” The performance was “worthy of such rock emporiums as San Francisco’s Avalon or the Fillmore West.” And “despite nearly unbearable heat, they had everyone in the place bouncing and screaming for more.”

As for the venue itself, he gave it a “triple-A rating,” but agreed that it was too small, at least for that particular show.

And as for the opening act, Blackwood Apology somehow became Black Widow Apology in his review. That was the first and last review I’ve ever seen from Mr. Mathiesen.

MINNESOTA DAILY, February 7, 1969

Tim Boxell was impressed by the “massive turnout” and mused, “This may just be what Minneapolis needs.” Boxell wasn’t impressed with the Dead’s music or efficiency in setting up, but liked the venue, although it was way too small for the crowd that showed up.

The market for this sort of entertainment is here, and David Anthony has big talent booked for the future. Perhaps now the Twin Cities can see the best groups for less and the bands that depend on audience involvement can succeed.

MINNESOTA DAILY, February 7, 1969

Another review in the Daily by Marshall Fine was enthusiastically titled “Just what Minneapolis Needs.” “Big time rock music has finally made it fulltime in Minneapolis.” He reported that more than 2,000 people had shown up at the venue, “which had a purported capacity of 1650.”

CONNIE’S INSIDER, February 15 – 22, 1969

After only one show, Connie gave the Temple exemplary marks. Connie was a jazz artist, older, and not a “head,” so he was playing catch-up to this new sound.

LABOR TEMPLE DRAWS HEAD MUSIC FANS

The Minneapolis Labor Temple, converted on Sunday eveningss to a temple of the best in “head, underground or and psychedelic” sound, has become to the Twin Cities what the Fillmore and Avalon have become to the West Coast scene, and what the Kinetic Playground has become to Chicago. The Temple is the showcase for the national acts which do their thing within the categor or framework (if any exists) of this kind of sound. (Note: The Twin Cities has long had The New City Opera House, a showcase for the bes in local-regional underground talent, and the possesser of a first rate light show.)

CONNIE’S INSIDER, February 15 – 22, 1969

The review of the Grateful Dead show itself was written by Will Shapira, the Insider’s regular concert reviewer. He noted that the called the show, which drew 1,600 to the “musty old hall” as “memorable and exciting.” He deemed the solo guitar work absolutely first-rate, on the level of the best jazzmen. He called the booking of the Dead a “masterstroke” as their first venture, and they should be brought back in the near future – which they were!

Shapira found the 90-minute set of the Blackwood Apology highly impressive, including some exciting organ work. They generated considerable excitement among the audience, which then “cooled it for about 45 minutes while electronic problems in the Dead’s equipment were straightened out.”

ROBERT BORCHERT

Bob wasn’t a music critic, but a fan who was there that night. Here are his memories:

The first time I saw the Dead was February 2, 1969, at the Minneapolis Labor Temple. I was an Airplane freak at the time but my friends were already Dead Heads with only the limited exposure of the first Warner Bros album and Aoxomoxoa. They saw to it that I came along.

The Hells Angels were overseeing the entry, stationed along the two flights of narrow stairs leading up to the third floor Union Hall where they were lingering about in the wings. The Minnesota Hells probably had 6-8 members but it seemed like dozens. The stage was about three feet above the main floor which had no seating, at least in the front half. The balcony may have had seating, but I never left the “dance floor.” I imagine the balcony as having a heavy curving wooden railing.

The band never really “took the stage.” People were just milling about. Some picking up instruments. I didn’t know who was who. An impressive looking man with very long hair tied back in a pony tail was at a microphone at the front of the stage. He appeared to be testing the sound and speaking in some kind of musical/audio code to an unseen person. “That’s Lesh,” my friend told me. ” He has perfect pitch.”

They gradually worked into a tune and an hour and a half later we had never stopped dancing. I didn’t even know they were a dance band. We figured we must be the best audience they had ever had, not knowing that the camaraderie and electricity between band and audience was standard Grateful Dead fare. Afterwards, if you asked me, I would have said we danced to “Lovelight” the whole night. When Live/Dead came out I realized, “Oh, yah, they played all that and more.”

Over the years I became confused between what I’d actually heard and what was on Live/Dead and began to doubt my own memory of the show. I downloaded the “tape” of the show several months ago and was delighted that I remembered it correctly. It really was Live/Dead and much much more.

Local band Blackwood Apology performed their rock opera “House of Leather” to open.

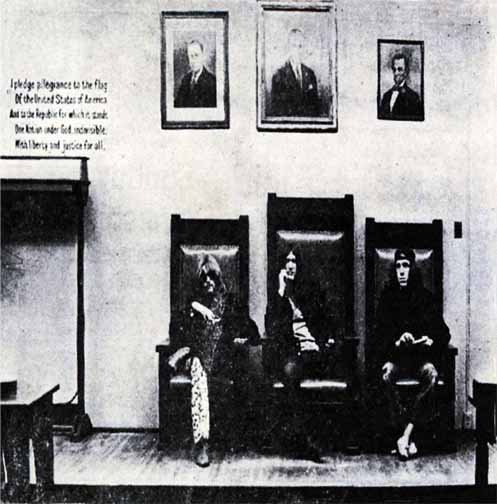

The photo below is of Blackwood Apology just before going on stage. Pictured left to right are Bruce Pedalty, Dale Menten, Joe Piazza, Dik Hedlund, with Dennis Libby in front.

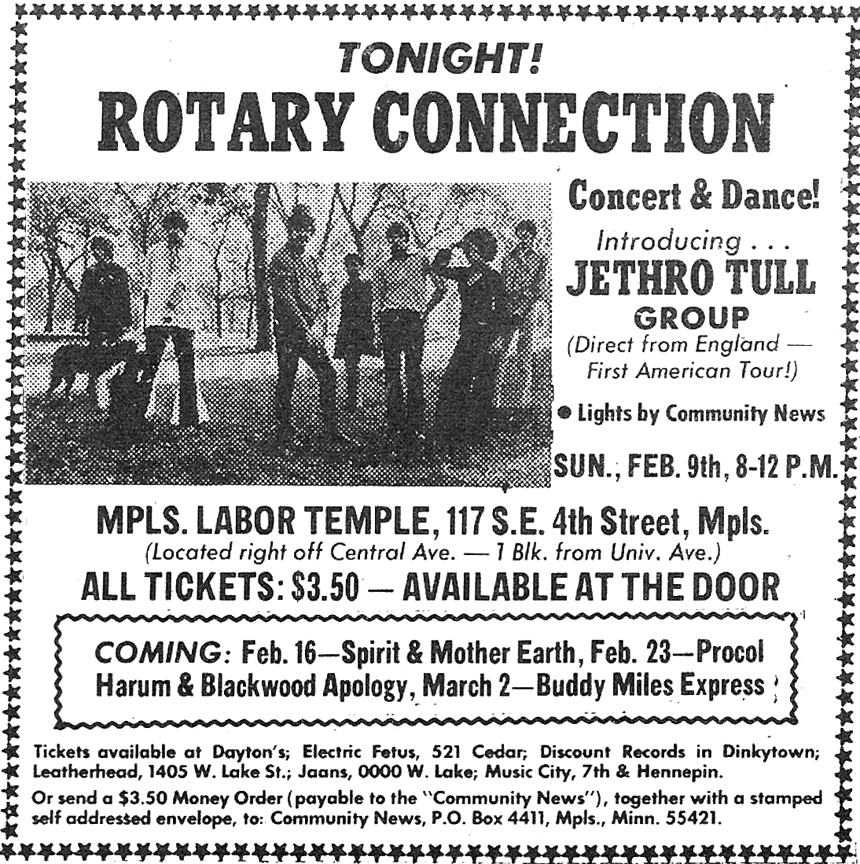

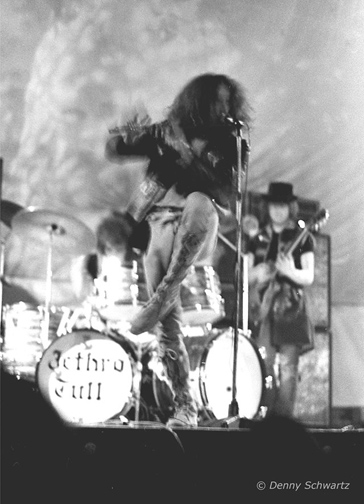

JETHRO TULL AND ROTARY CONNECTION – February 9, 1969

CONNIE’S INSIDER, February 15 – 22, 1969

Will Shapira reported that a good crowd of about 1,000 filled the Temple to hear this four-hour show.

Connection, a six-piece band, pleased the audience with a set of well-rehearsed, always interessting songs, most of which featured the vocalist, Minnie [Ripperton], who somehow is able to do with her voice what John Coltrane did with the soprano saxophone. The lofty sound, over a well-integrated line of organ and guitars, was shrill and exciting, but to some ears tolerable in short bursts only.

This was Jethro Tull’s first American tour and Shapira found him to be “extremely jazz-oriented and talented.” Tull alternated between harmonica and flute, and his solos “swung and soared beautifully.”

During the course of the varied set, Tull and crew presented a jazz flute duet, a transcription for flute of a Bach guitar piece, an extended, solid guitar solo by Martin Barnes, and a rollicking drum solo to close the group’s highly impressive performance.

The most accurate summation of the evening came from Tull himself when he let us in on the current English phrase used to describe a pleasurable occasion or experience: “Supergroovycool!”

WARREN WALSH

As I recall it was another one of those nasty cold Minnesota nights. It was a Sunday night and there couldn’t have been more then a couple of hundred people there. Jethro Tull was just releasing their first album and nobody knew who they were [their first US stop]. We didn’t care much for the Rotary Connection but it beat sitting around on a Sunday evening. We sat on the floor about 10-20 feet from the low stage. Can’t remember the Rotary Connection but Jethro Tull took our heads off! During the break Ian Anderson just stepped down and mixed with the crowd. I remember him sharing some cigarettes with a few of us stand near the front.

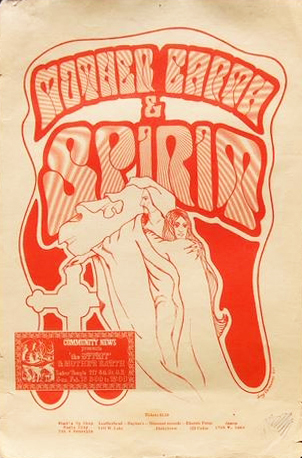

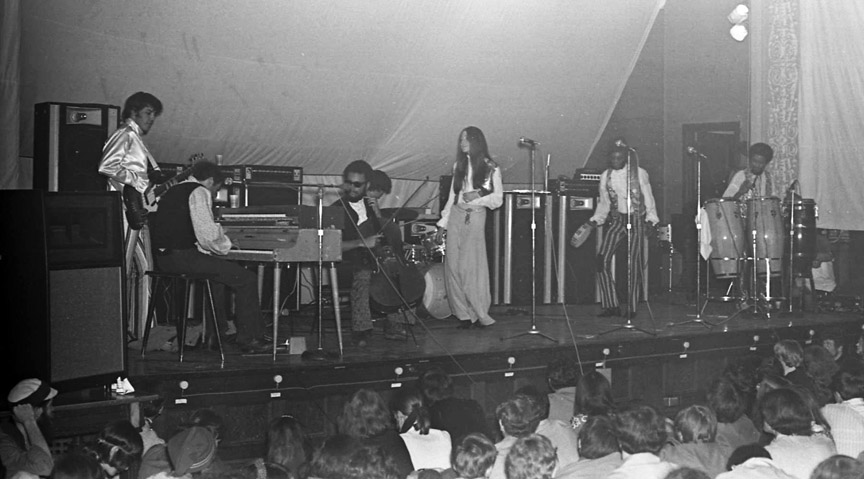

SPIRIT AND MOTHER EARTH WITH CLOVER: February 16, 1969

CONNIE’S INSIDER, March 1 – 8, 1969

Will Shapira noted that it was becoming “squashingly evident” during Spirit’s concert that Anthony and Community News may need a larger hall for their concerts if things continued as they were. A turn-away audience of 1,300 jammed the room.

After running through several of their shorter, better-known songs, Spirit stretched out in an extended suite called “Elijah.” Set in 6/8 time and using a simple but pleasing melody that could have been written by Dave Brubeck, the piece served as a launching pad for extended solo flights by all members of the band. The lead guitarist wanged out some fantasstic, mind-bending electrionic runs which he carried to eardrum-shattering heights, only to switch off completely and take up a down-home blues line that gassed the crowd.

The conga drummer and the trap drummer also contributed some good things, esspecially the latter, whose work, often in 3/4 and 6/8 time, was remindful of ssome of the great techniquest that juzz drummer Max Roach introduced in the 1950s.

Shapira reported that Mother Earth was a large group that alternated between R&B and country rock. Their sound was less celebral, but more people danced. Their singer, Tracy Nelson, had throat trouble, and literally sat out the concert and stuck to her knitting back stage.

KEVIN ODEGARD

Kevin Odegard remembers this about Spirit:

This was the first of two performances by this phenomenal band at the Labor Temple in 1969. Their gear was ragged yet soulful. Fender amps with Ampeg bass amp. Fantastic sound all around on this night.

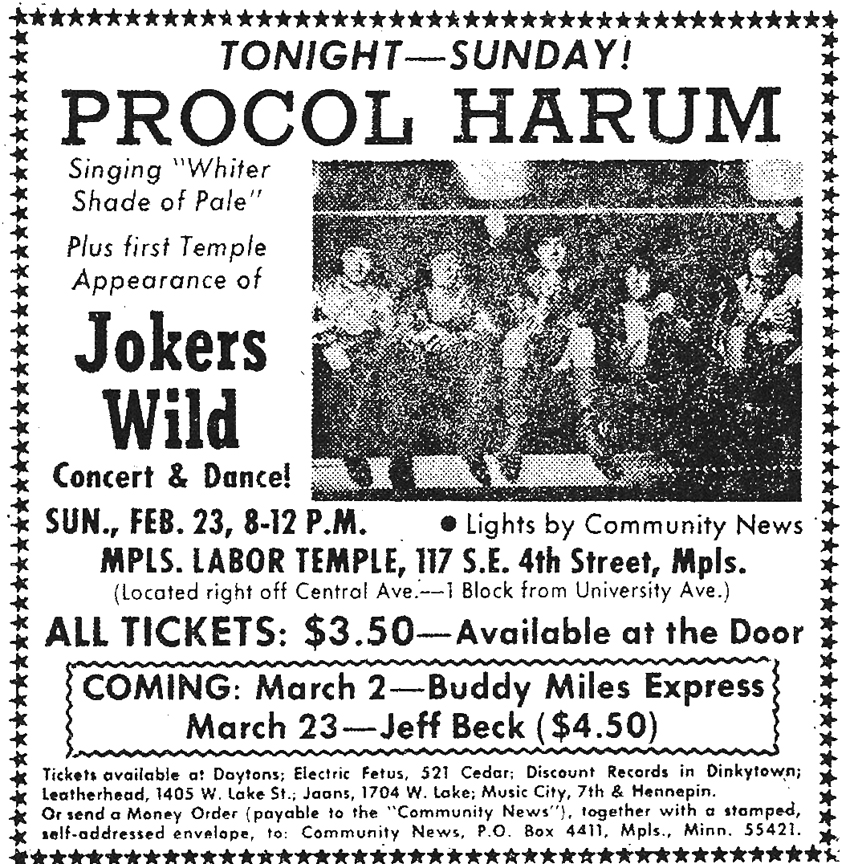

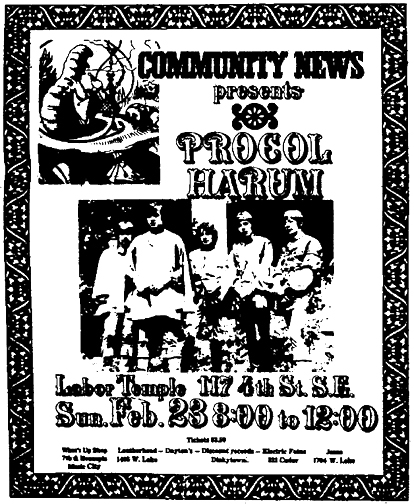

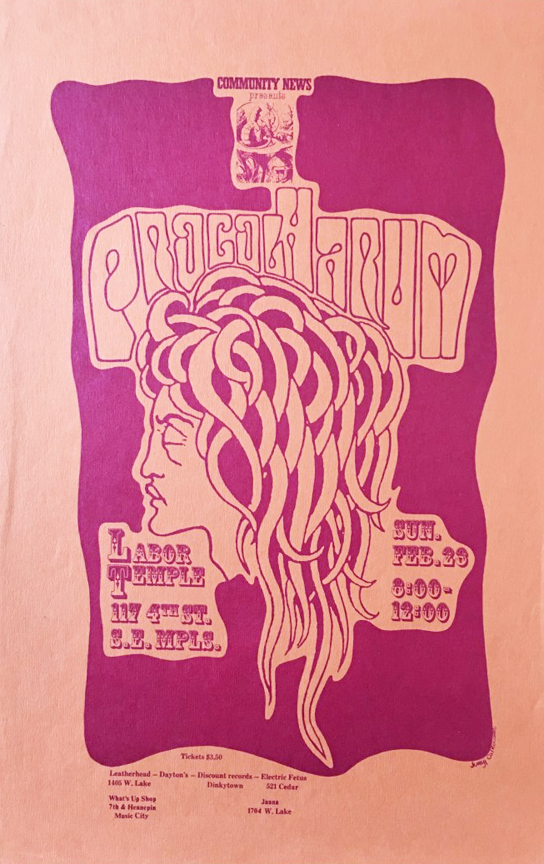

PROCOL HARUM AND JOKERS WILD – February 23, 1969.

Original ad showed Fraternity of Man and Mother Earth.

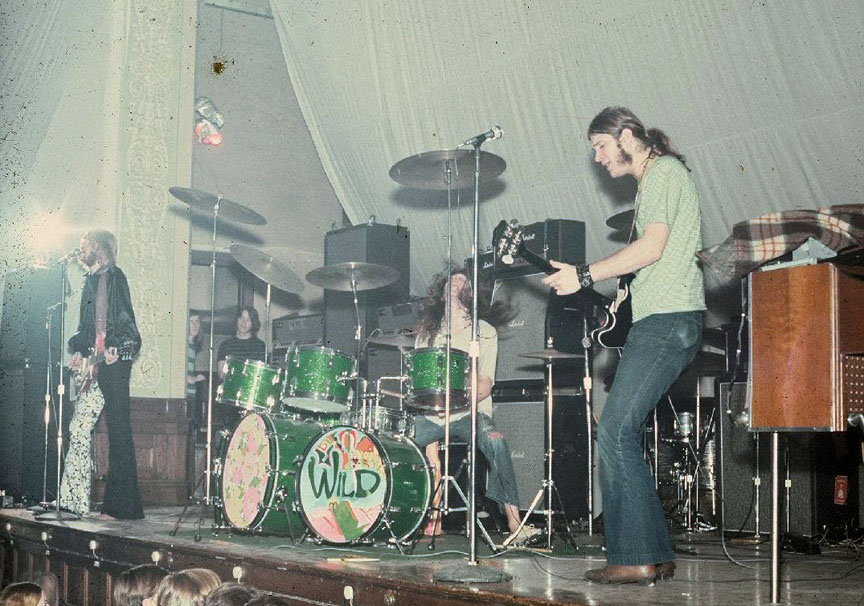

The show was opened by local group Jokers Wild, replacing the originally-scheduled Blackwood Apology. The photo below shows the JW in the crazy three-seat couch thing in the basement dressing room before the show. The photo was part of a spread in the Minneapolis Tribune about the Labor Temple on March 2, 1969.

The following photos of Jokers Wild opening the show are courtesy minniepaulmusic.com

MINNEAPOLIS TRIBUNE, March 2, 1969

Entertainment columnist Allan Holbert reviewed this show and the Temple in general. Holbert seemed extraordinarily interested in all the hair – on the performers and on the listeners.

He was also very interested – or was he making fun of – the “weird costumes” – “see how the nonconformists conform..” He described:

- beads and bell bottoms

- the girl in the long lace dress and no underwear whatsoever. He even thoughtfully provided a photo of this young woman.

- the clever boy who had made himself a cape by splitting an old pair of pants

- Susie Cream Cheeses with their long, straight blonde hair and their big, flowered hats

- funny fur coats they found in grandmother’s attic

Holbert also described Community News’ light show, projected on three giant screens behind and to each side of the band:

weird, brightly colored images keep changing forms. Out of a big, purple, pulsating amoeba rides a cowboy from a black-and-white silent movie. An Andy Panda cartoon starts shaking and is, all of a sudden, a pink-and-orange geometric design. What look like big blobs of blood transform themselves into gaudy, green holes that could be pock marks on a face or craters on the moon.

He even described the air: “Instead of air there is a sweet-smelling, smoky smog caused by heat, sweat, incense and tobacco and maybe other leaves that burn.”

As for the music,

.. the Jokers Wild present some wild, crashing rock that will turn out, in the minds of most listeners, to be better than that to be presented later by the foreign group [Procol Harum].

Well, despite his obviously square, misogynist, and cynical viewpoints, Holbert does give us a window into the Wonderful World of the Labor Temple.

CONNIE’S INSIDER, March 1 – 8, 1969

Connie confessed that he was only there for a few minutes and regular reviewer Will Shapira couldn’t attend, so he couldn’t provide a regular review. Connie was backstage while the Jokers Wild were on, though, and he was impressed at the audience response. He also noted how hard the guys worked; drummer Pete Huber went through eight drum sticks just while he was listening!

Procol Harum’s sound seemed to echo classical works as well as jazz riffs and passages – Connie found the musicians to be outstanding.

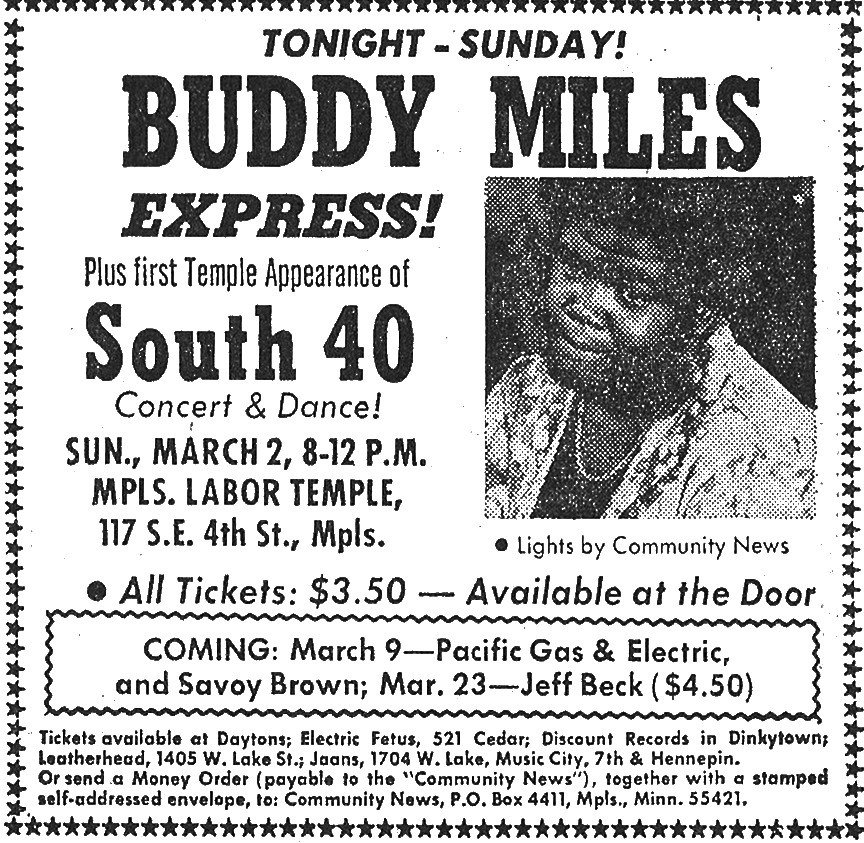

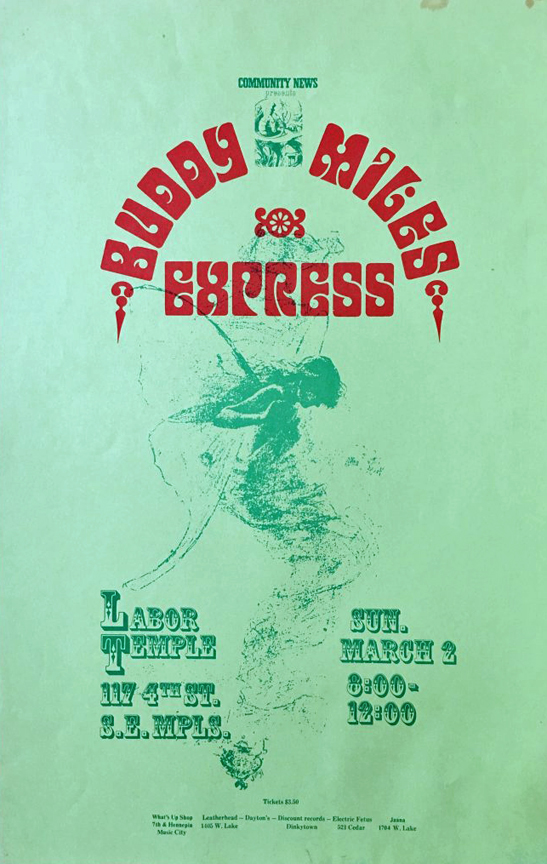

BUDDY MIILES EXPRESS AND SOUTH 40 – March 2, 1969

CONNIE’S INSIDER, March 1 – 8, 1969

Connie admits again that neither he nor Will Shapira were able to see enough of the show to write a full review, and what he wrote may be based on what he heard. I will quote Connie’s remarks; note that his use of the word “colored” was undoubtedly not used as a perjorative, but an indication of Connie’s age. I’ll bet he caught hell for it, and he would go on to write extensively about black musicians.

Buddy is a true cannonball on drums, with one of the best op horn sections in the bussiness. This band plays blues-rock with a twist wich isn’t found in Blood, Sweat and Tears. It’s more colored blues oriiented than the Tears, who lean more towards jazz licks and musicianship. That might be because the horn section was all colored, bix. (sic)

Connie missed the South 40 completely, but heard from fans that they put on a good show. “They’re all good musicians, and they got Denny Craswell on drums, and he’s very good!”

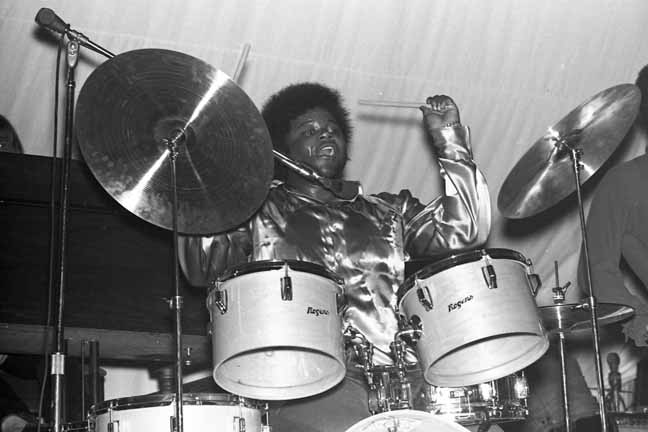

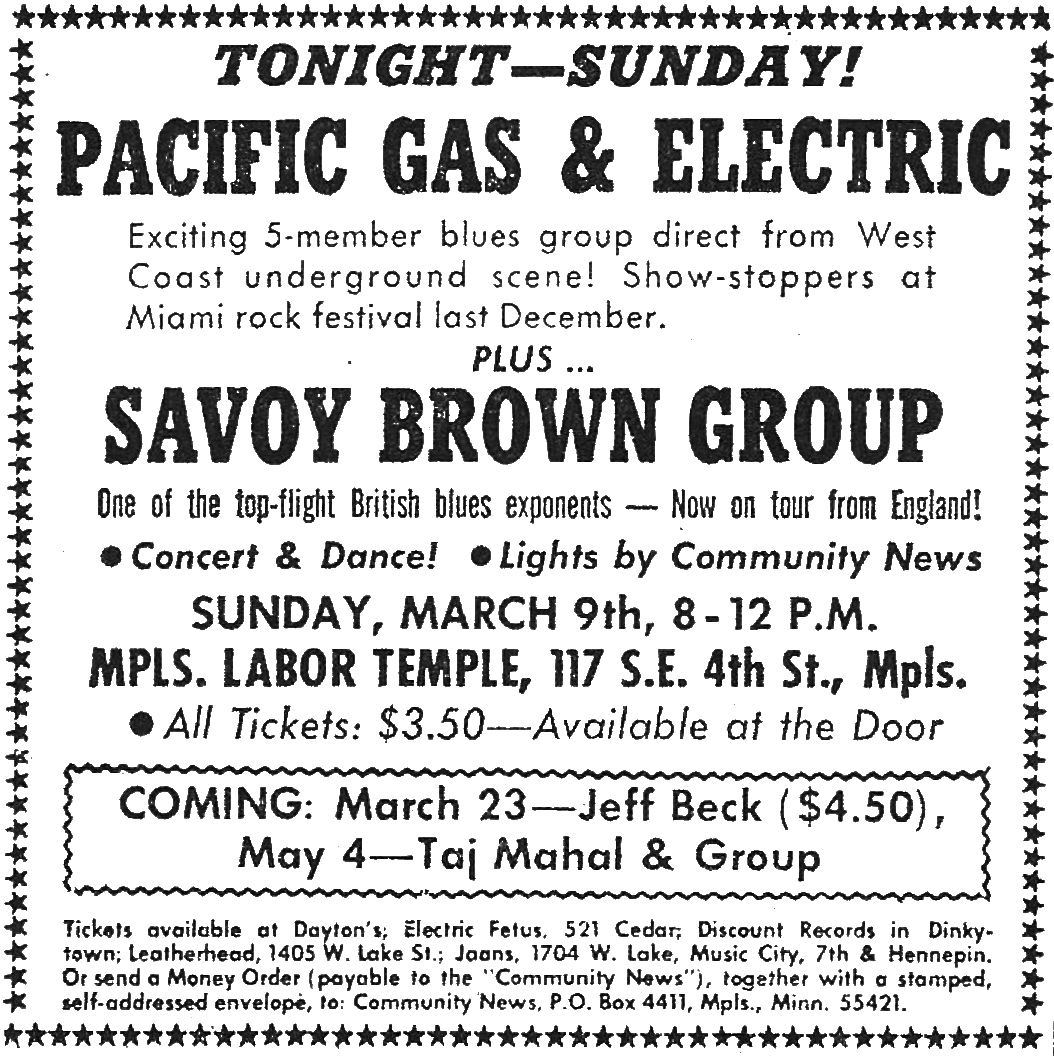

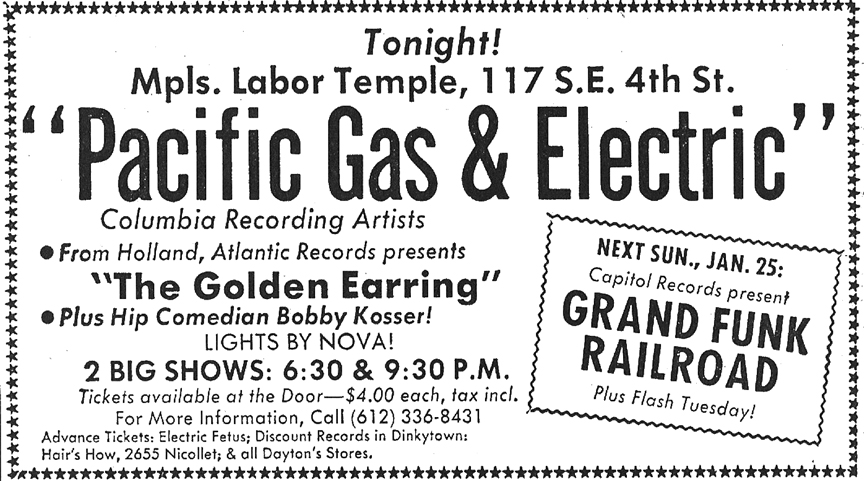

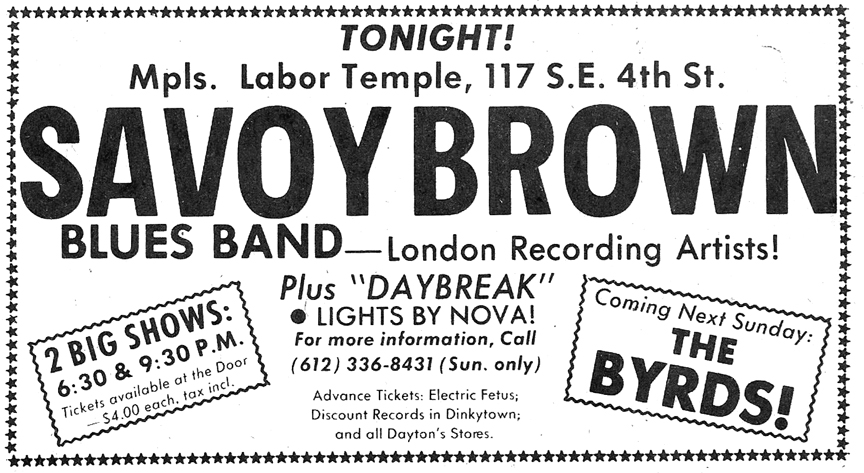

PACIFIC GAS & ELECTRIC AND SAVOY BROWN – March 9, 1969

This was Savoy Brown’s first American tour and they would come back to the Cities many times. Local folk group Dawn opened the show.

CONNIE’S INSIDER, March 22 – 29, 1969

Although no byline was given, this review was probably written by Will Shapira. It was was called the best double-bill yet, with both groups emphasizing a deep, gutty approach to the blues. Savoy Brown stressed instrumental solos, while PG&E’s lead singer “got to the highly enthusiastic audience with his soulful shouts and wails.”

This was Savoy Brown’s first American tour, and they “hauled out and resuscitated such forms as boogie-woogie and rock and roll.” They also presented a satirical montage of boogie and early rock, and the reviewer opined that “it would have been good to hear the group for an entire evening.

PG&E evoked some spirited dancing, hand clapping, and shouting, but didn’t reach the heights of Savoy Brown. Its guitarists did take several high-flying solos, though.

“The concert was another groove in what seems to be a never ending series of grooves.”

DAWN: This was a folk trio with Dean Carr, Joyce Everson and Ken Schaffer. Ken remembers:

Kim, the Lead Guitar Player for Savoy Brown, was quite taken by Joyce Everson and ended up taking her to England for Elton John’s people to help her out. They ended up producing an album for Joyce.

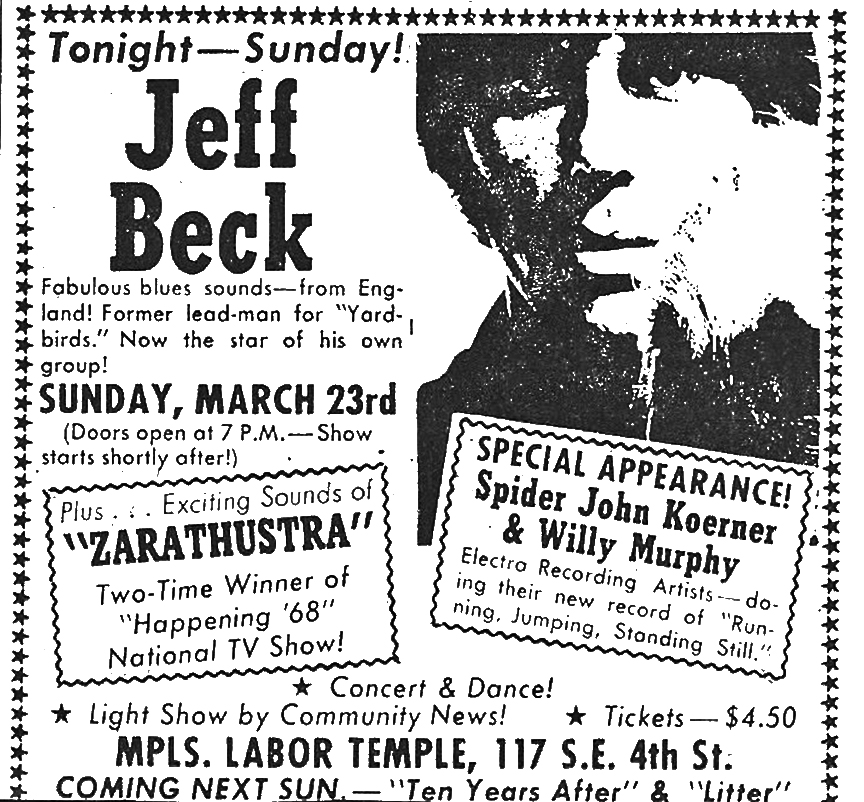

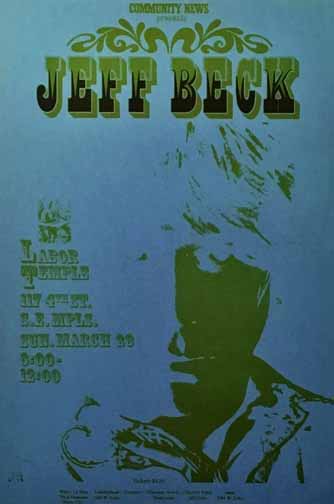

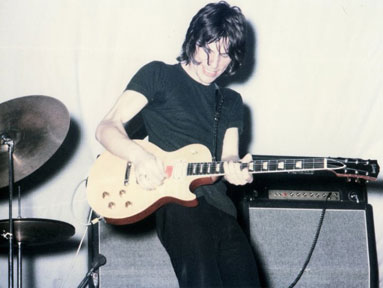

JEFF BECK GROUP, ZARATHUSTRA, SPIDER JOHN KOERNER, AND WILLIE MURPHY – March 23, 1969

At this point Rod Stewart was singing with Jeff Beck, and Steven Adams remembers that “when the sound system kept cutting out Stewart threw the mike stand through an amp and walked off the stage, never to return, despite a standing ovation.” Stewart left the group that July.

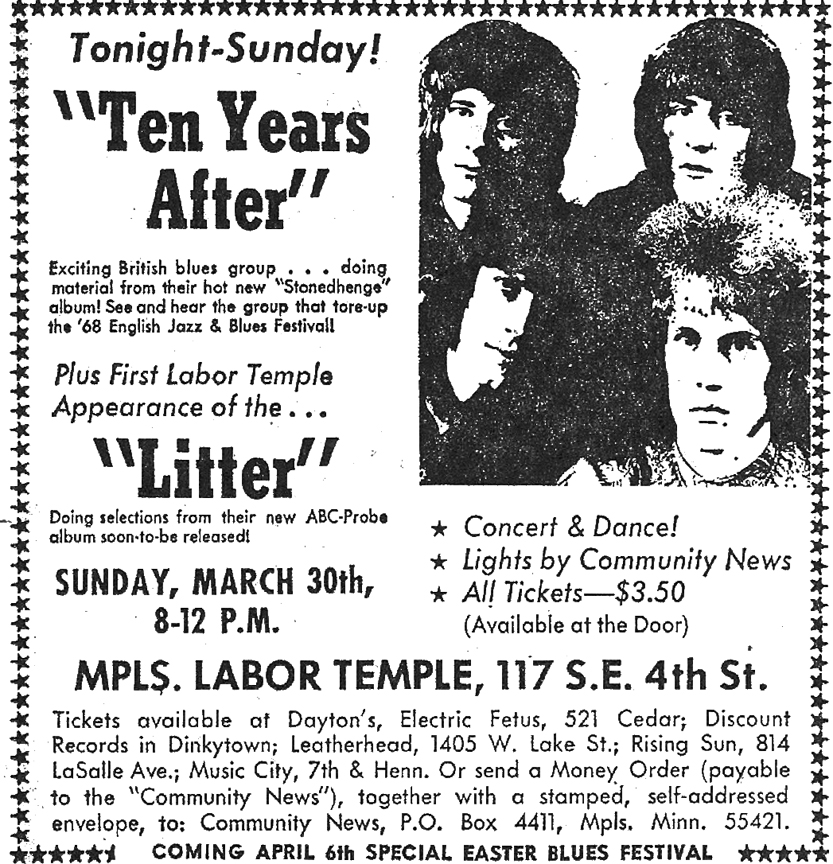

TEN YEARS AFTER AND THE LITTER – March 30, 1969

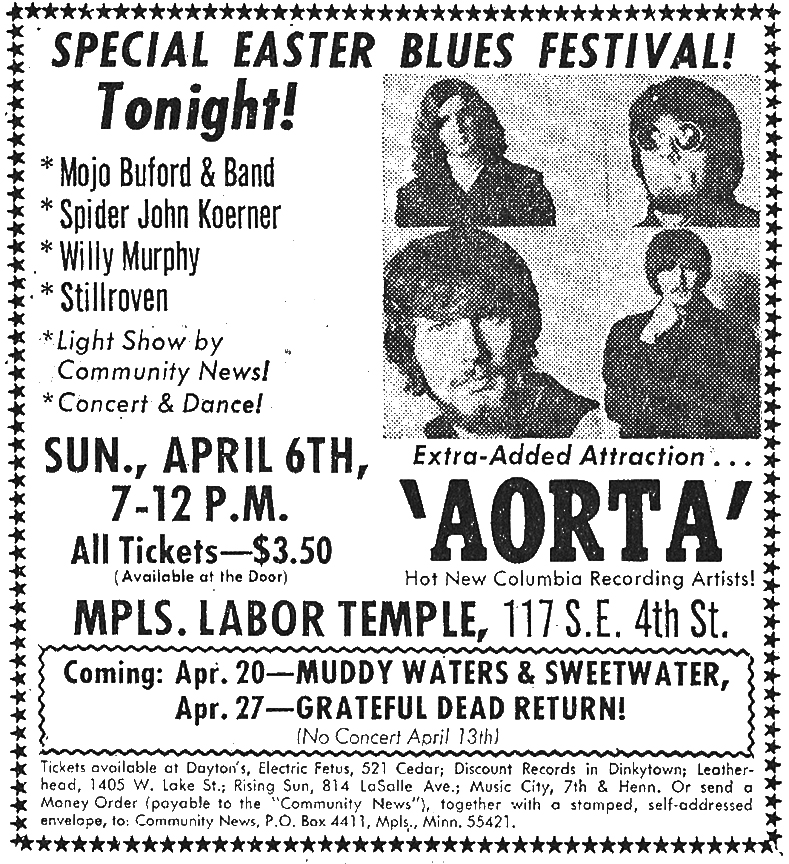

EASTER BLUES FESTIVAL – April 6, 1969

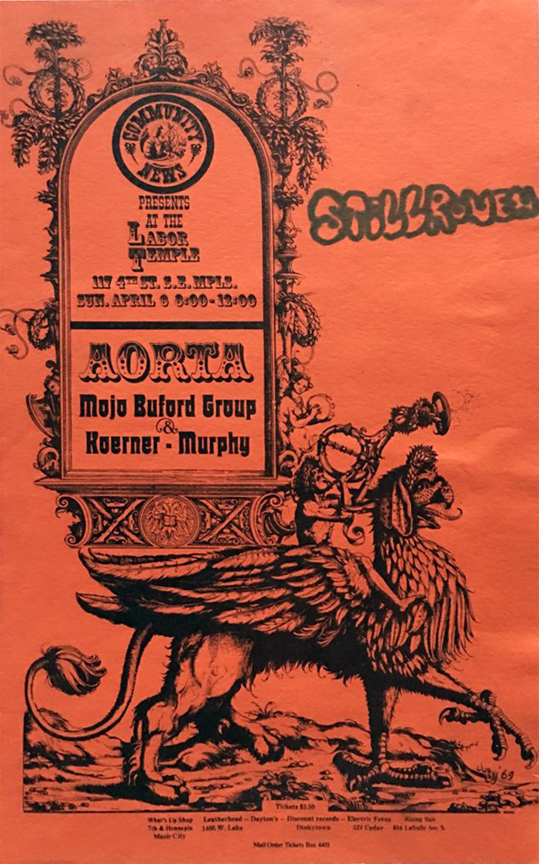

Advertised on posters, etc. were:

- Aorta

- Mojo Buford

- Stillroven

- Spider John Koerner

- Willie Murphy

A blurb in the Tribune on the day of the show also included:

- Tony Glover

- Dave Ray

- The Mill City Blues Band

CONNIE’S INSIDER, April 12 – 19, 1969

Spider John Koerner started the show with “a fine set of gutty vocals, many of which were augmented by some mellow lead guitar and piano solos.”

Mojo Buford was next, alternating with a second lead singer whose name was lost to time and space. They sang “some good, dirty bluess and both wailed nothing but blues on harmonica.”

“The Stillroven produced the smashingest sounds of the evening. Its vocal work was strong and there were several exciting guitar runs … The band sounds better than ever.”

Aorta was a national act with a set that was decidedly not the blues. But the audience dug it, “perhaps because the group was propelled by a slashing, really fine drummer and because its songs were well rehearsed if constructed of rather thin psychedelic material.”

An attempt to describe the two films that Community News showed was so convoluted that I’m too confused to try to translate. Something about Mickey Mouse and Carole Landis.

April 13, 1969: No Concert

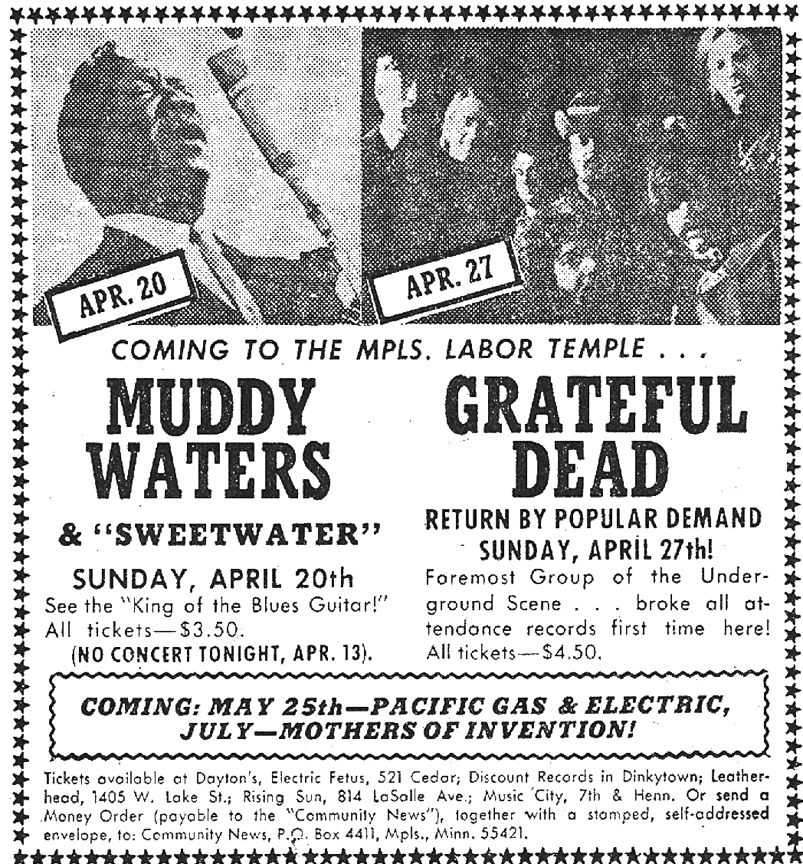

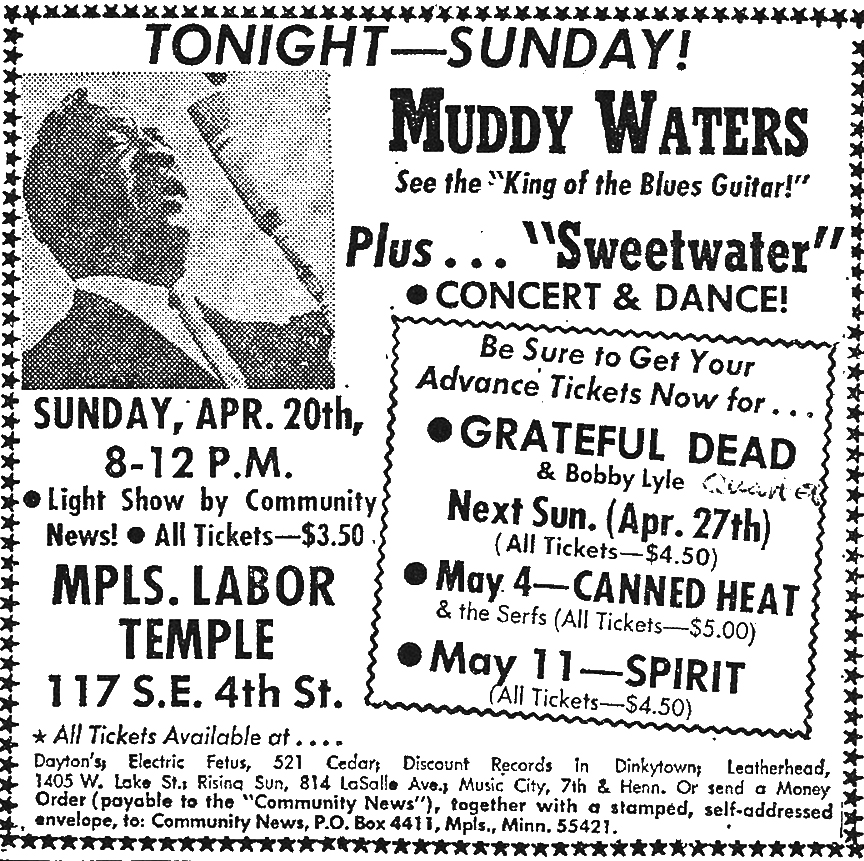

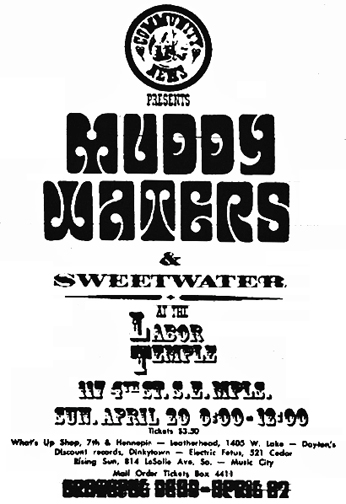

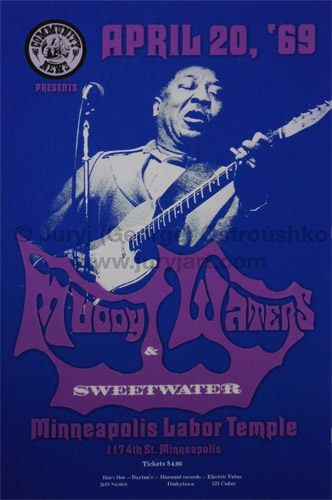

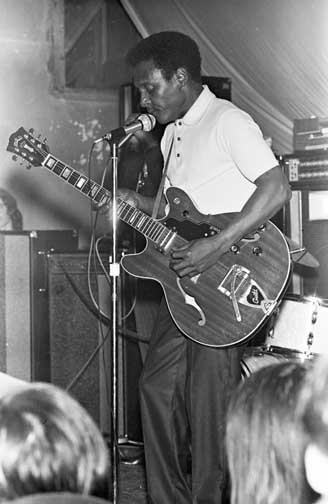

MUDDY WATERS AND SWEETWATER – April 20, 1969

MINNEAPOLIS STAR, April 22, 1969

Marshall Fine, then a U of M student, found the Muddy Waters/Sweetwater show “one of the best musical evenings the Twin Cities has seen in the last six months,” high praise indeed! Muddy Waters began with a short set, sticking to the blues instead of what Fine called the “psychedelic” band on his last album.

After a half hour break, Sweetwater “brought the audience to its feet and onto the stage with their exciting mixture of rock, classical and calypso music.” Muddy Waters came back for three more songs, including his signature “Hootchie-Kootichie Man,” and the crowd went home happy.

CONNIE’S INSIDER, April 26 – May 3, 1969

Muddy Waters appeared with a R&B sextet. His opening set included “Work Song” and “Hoochie Coochie Man,” and several “slow, funky original laments.”

Sweetwater’s conga drums provided an exciting beat, and an electric cello produced effects such as “the ear-piercing psychedelic,” “a jazz-like walking bass, and guitar-like picking.” Other instruments included a flute, electric piano, and vocal soloists. The high point was a half-hour song that featured an unnamed musician on the electric keyboard and harmonica. Dancing and stage rushing ensued.

At the second show, Muddy introduced his second guitar player as “Peewee” – “who also sang well.”

“In all, it was another exciting scene at the Temple and a return engagement for both groups would seem a must, judging by audience response on that warm and groovy night.”

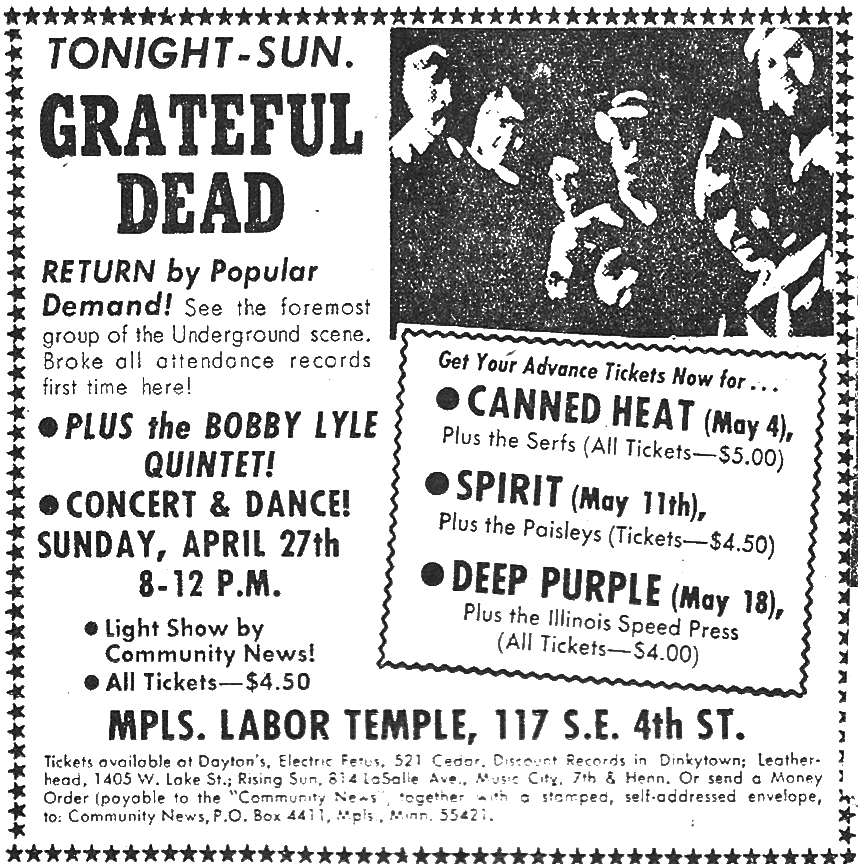

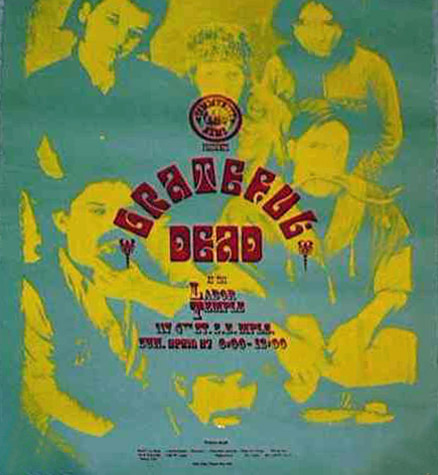

GRATEFUL DEAD AND THE BOBBY LYLE QUINTET – April 27, 1969

MINNEAPOLIS STAR, April 28, 1969

It was a little difficult to tell whether Marshall Fine liked the Dead or not. “They have no distinctive style because they borrow from a number of types of music. Yet the sound, indistinctive as it may be, is their own. The Dead provided a pastiche of styles and a uniqueness of sound.” One song lasted an hour, beginning with “Turn on Your Love Love Light.”

Fine thought that the Bobby Lyle Quintet was out of place, “playing jazz that would have been appropropriate in a supper club,” but “a nice change of pace to the Temple crowd.”

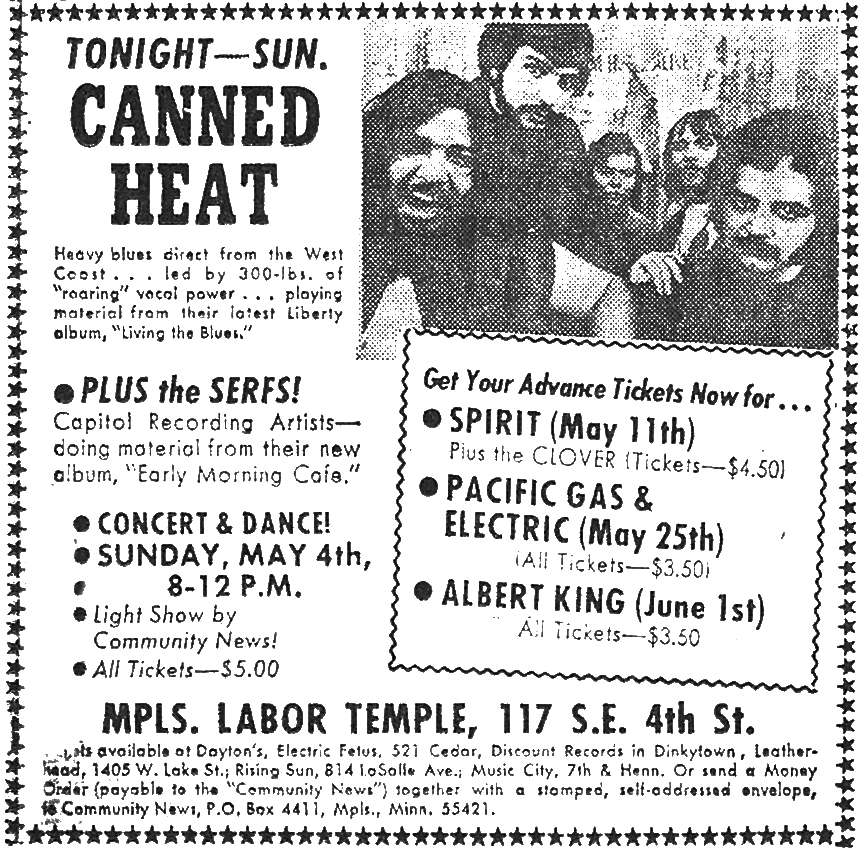

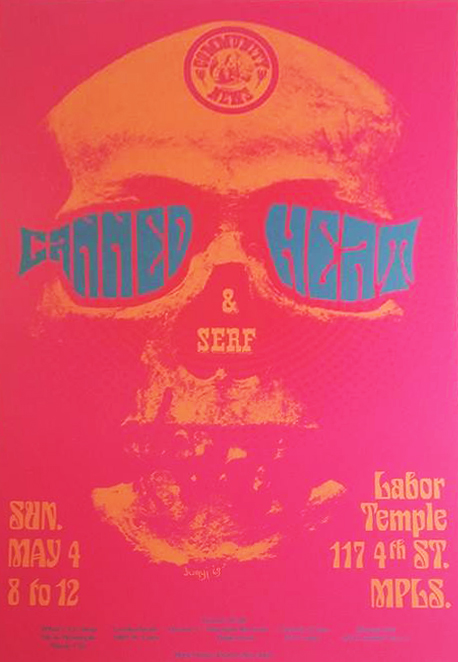

CANNED HEAT AND THE SERFS – May 4, 1969

Taj Mahal was originally scheduled.

The poster below of Canned Heat is not the original printing. George Ostroushko uncovered the original artwork tucked away in one of his portfolios. The poster for this show was actually an oversized silk screen poster and very few were ever printed, so very few if any survived. Georg reissued it using a different color scheme.

Charlie Campbell remembers that when Canned Heat launched into “Boogie” the crowd formed a conga line that snaked outside the building and back in! Vernon remembers the police pulling the plug on the band at 12:30!

MINNEAPOLIS STAR, May 5, 1969

Marshall Fine commented on the “non-discriminatory” Labor Temple audience that cheered at anything. Canned Heat seemed to play more instrumentals than vocals: “They play all right but they don’t know when to stop. There is a line that divides good playing from wretched excess and they are continually crossing it.” The word “narcissism” was used.

The Serfs, from Wichita, were:

fast and tight and tight and knew when to call it quits with their instrumentally oriented numbers. They played a lively combination of rock, blues and jazz and showed the unique psychological know-how of leaving the audience seriously pleading for more. Canned Heat could take a lesson or two in that.

CONNIE’S INSIDER, May 17 – 24, 1969

Canned Heat was a gas until guitarist Henry Vestine lost himself in electronicsland during an extended set-closing performance of “Reef Ride Boogie.” Until then, the band had inspired the audience into a snake dance that twice wound its way from the main level up to the balcony with its sauna-like atmosphere. The group reachess tremendous emotional heights when belting out its patented blues-boogie things and why Vestine had to jump into that unmusical and ultimately boring electronics bag is a mystery.

The Serfs got an excellent review, playing as well or better than Canned Heat. The young jazz-rock band turned in a consistently “interesting and swinging set.” Most of the solos were taken by Freddy Smith on the tenor sax. Rick Margolis played the vibes with “cool, tense, lines.” Larry Faucette added several virtuoso solos on congas. The group was was called back for two encores.

IVORY TOWER

In the May 1969 issue of the Ivory Tower (a publication of the Minnesota Daily,) Tim Boxell wrote a piece on the local music scene, entitled “Rock is Alive in Minneapolis – But is it Well?” In it he discussed several venues, such as Someplace Else, Casino Royale, the New City Opera House, and Dania Hall. Most of his discussion was given over to the Labor Temple, however, and I will quote liberally.

Anthony offers a big-name rock show on a regular basis at $3.50 a shot, a light show, a wood floor to sit or daance on, and a place where the acoustics get the sound to you. The home of the area’s unions was converted to Minneapolis’ Care Package for the music-starved populace. Will it succeed?

So far Anthony and the Community News have managed to overcome difficulties which are by no means small. Plagued by capacity restrictions applied by the Fire Marshal after the initial planning and investment had been made, the lack of a real dressing room, a tiny stage, and a pervasive sense of the temporary, the place has nonetheless made headway. Limited capacity still remains the greatest problem and is truly a hindrance.

[The limited audience limits the amount Anthony can pay bands, and if bands want a percentage of the house, a small house is a disincentive to play.]

Anthony could go commercial and pack the place with boppers by booking Ohio Express, etc. Instead he maintains a definite standard in his choices, and has thus gained an appreciative following. In spite of costs, he has managed to bring in a pleasing variety of talent ranging from blues to acid and art rock. Proximity to Chicago has made Sunday evening in Minneapolis a desirable extra appearance for touring bands would be otherwise difficult to obtain. But the Temple could use a larger building if it hopes to attract the expensive artists.

How long will it last? Avalon ballroom and Kaleidoscope folded on the West Coast for reassons that could apply here. The Byrds, Glenn Campbell, and even the Beatles now are making a transition to the country western sound. Will the market for rock survive? Finally, can rock escape the repressive Establishment powers working against it, plus the indictment that its sound is a cause of early deafness and accompanying strobe lights are seriously damaging to sight?

Dance places, of course, will survive regardless of changes in music. And theatrical productions using rock music, such as the “House of Leather,” might be a successful and lasting development. But unless a better location for the Labor Temple audience can be found, the future for serious listeners looks doubtful.

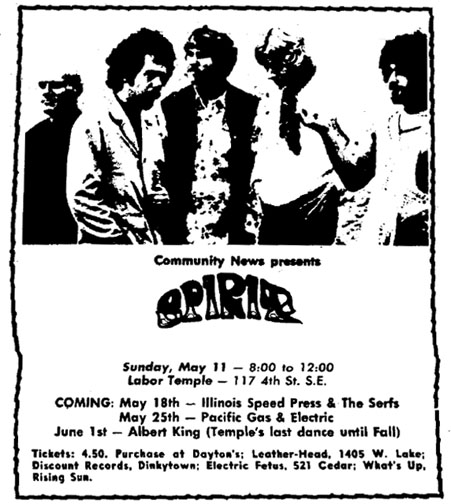

SPIRIT AND CLOVER – May 11, 1969

MINNEAPOLIS STAR, May 13, 1969

Marshall Fine described Spirit’s sound as refreshing – “like a pitcher of iced water on a hot day.” John Locke’s electric piano was “chime-like,” a perfect counterpoint to Randy California’s lead guitar. California sometimes “indulged in little amplifier concertos irrelevant to the song.” Fine’s only complaint was that the volume on the bass and the microphones was so high that the sound was muddy.

KEVIN ODEGARD

Kevin compared this show to Spirit’s February 16, 1969 show:

Seven months after their first appearance, Spirit returned to the Labor Temple with a back line and PA provided and sponsored by Sunn Amplifiers of Portland; specifically a new solid state model not driven by tubes like the Sunns used by The Who. Absent the funky Fender reverb and punch, this set was a mushy, nondescript, cardboard disaster start to finish, as if the band had sold their souls to the devil at the Crossroads.

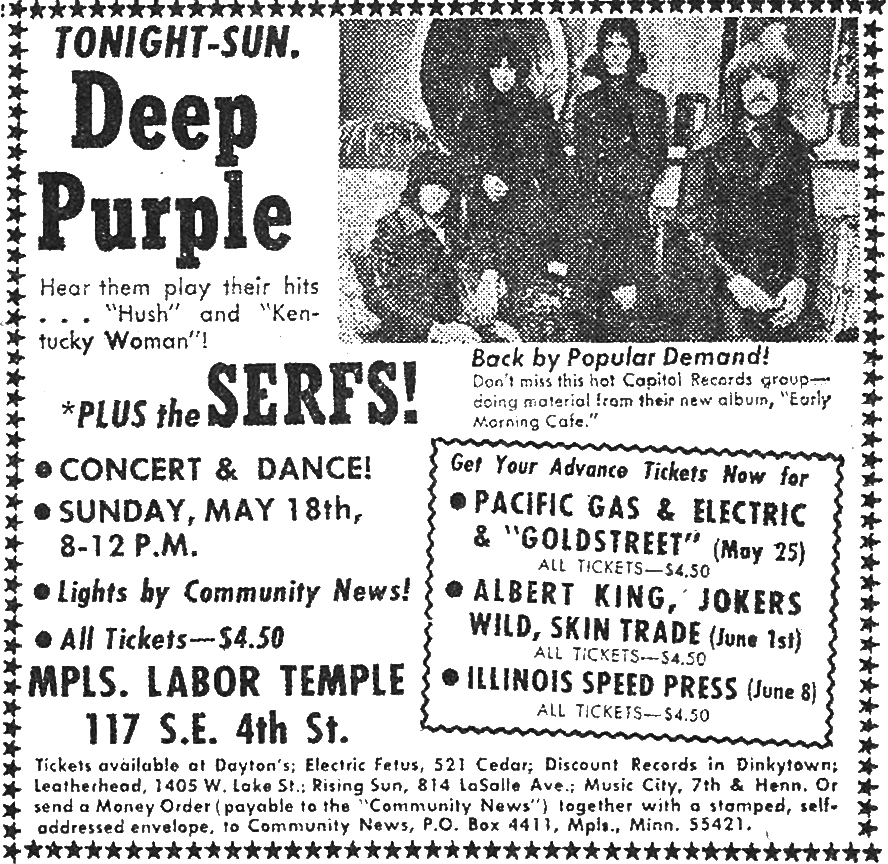

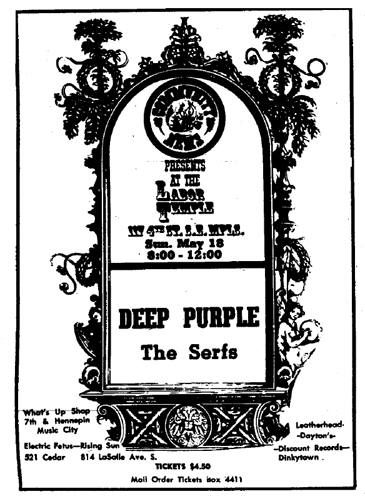

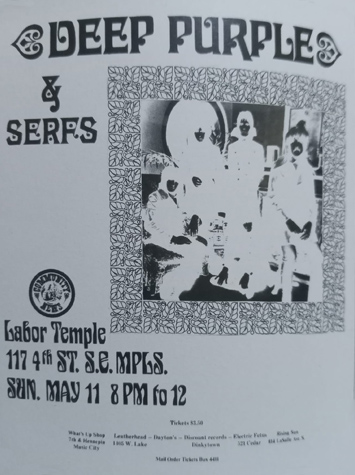

DEEP PURPLE AND THE SERFS – May 18, 1969

Illinois Speed Press was originally scheduled. There is a poster with that lineup, but I don’t have it.

The original poster for the show has been lost, but George Ostroushko, who drew the artwork, has shared the master from which a three-color silkscreen was made.

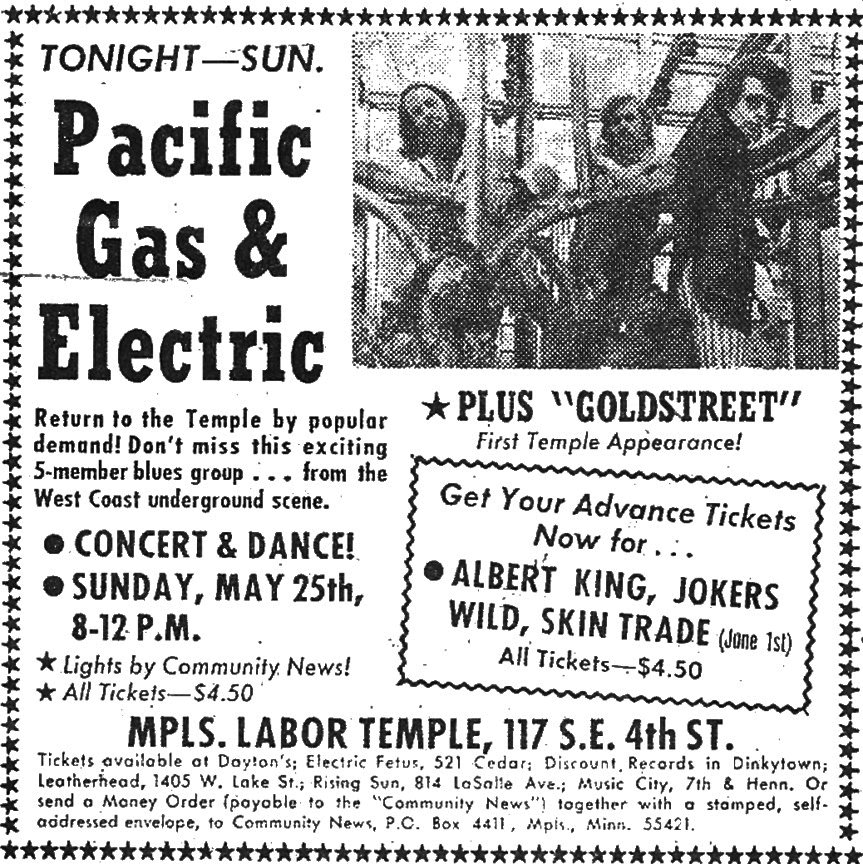

PACIFIC GAS & ELECTRIC AND GOLDSTREET – May 25, 1969

Some ads identified the warmup band as Tradewinds. Tradewinds changed its name to Goldstreet in May 1969. Members of Pepper Fog would later take the Goldstreet name in the early 1970s.

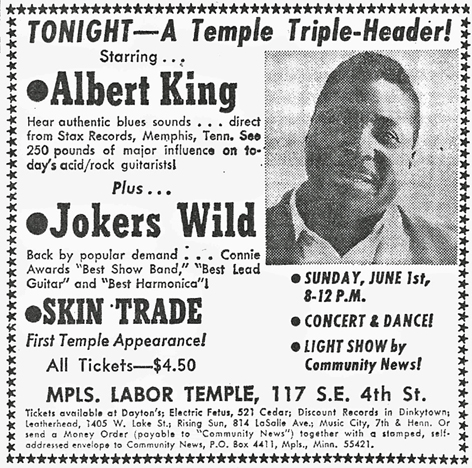

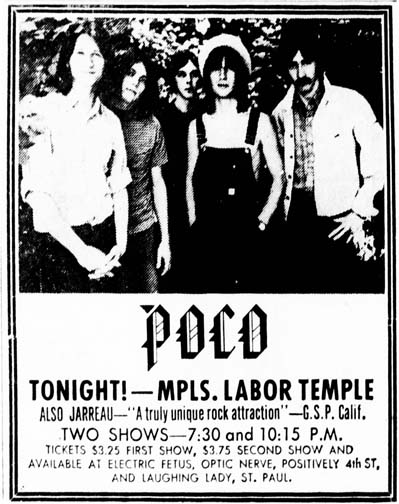

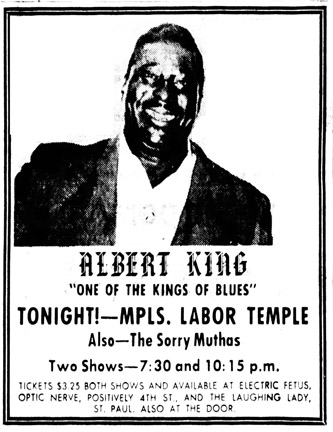

ALBERT KING, JOKERS WILD, AND SKIN TRADE – June 1, 1969

MINNEAPOLIS STAR, June 2, 1969

Marshall Fine described what really happened. Locals bands Skin Trade did 45 minute set, Jokers Wild played for an hour, and Scott Bartell, who was identified as the public relations director for Community News, told the crowd that Albert King was not coming. No refunds were offered, but tickets could be used the next time King appeared. This did not go over well for the 1,000 people who would have not otherwise spent $4.50 to see two local bands, good as they were; Fine reported that Bartell was greeted with “jeers, catcalls and a stream of shouted obscenities.”

EXIT CHARLIE CAMPBELL

There were no more shows in the near future: those planned for Illinois Speed Press (June 8), Paul Butterfield, and the Mothers of Invention never materialized. On July 5, 1969, it was announced that the Labor Temple “has closed for the summer.” Campbell felt that Community News got unjustly blamed for the Albert King fiasco and ended his relationship with David Anthony and the Labor Temple.

SKIN TRADE, C.A. QUINTET, AND UNDERGROUND SOUNDS – July 20, 1969

When Mike Barich sent me Ken Erwin’s itinerary of the C.A. Quintet for part of 1969 that included a show at the Labor Temple in July, I was … surprised. Ken didn’t remember much about the gig except for something very important: it was the night Neil Armstrong first stepped on the moon! Here’s what Ken did remember:

I looked it up and the moment happened right at about 10 pm. Psychedelic!

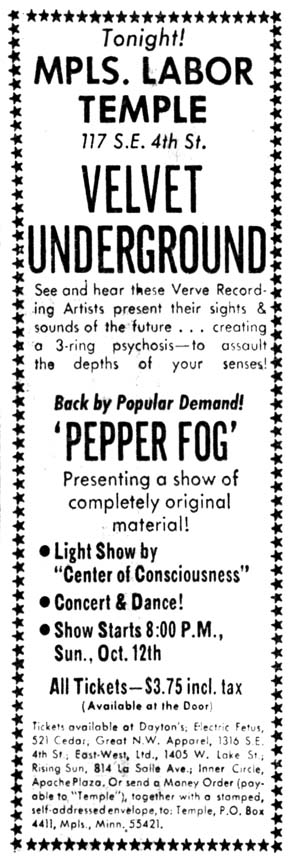

A NEW SEASON

David Anthony began a new season on his own at the Labor Temple in September 1969, with a new light company, Center of Consciousness. He said in an interview that he would have liked to run all summer, but without air conditioning it was impossible. He also mentioned other events such as showing films; “Yellow Submarine” was an example. (Minneapolis Star, September 19, 1969)

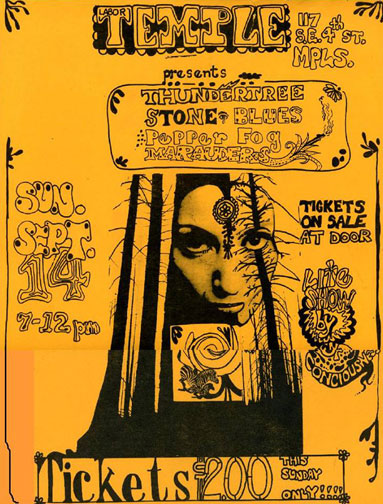

SEASON OPENER WITH FOUR LOCAL BANDS – September 14, 1969

- Thundertree

- Stone Blues

- Pepper Fog

- The Marauders

Unlike all of the others, the poster below was NOT the work of Juryj (“George”) Ostroushko.

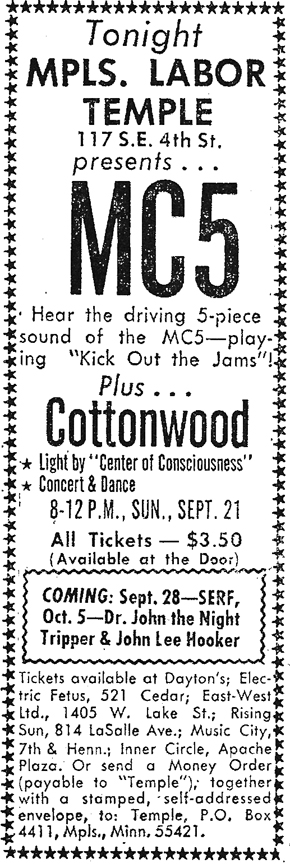

MC5 AND COTTONWOOD – September 21, 1969

MINNEAPOLIS STAR, September 22, 1969

Well, Marshall Fine did not dig the MC5. “Loud, Louder, Loudest,” was the header. The headline was “Rock group was so bad it was funny.” Yipes! He likened it to the old “Batman” series, where something was “so terrifically bad that the only possible reaction to it was fits of laughter.”

Many good lines in this review: