Race, Creed, and Color in the Twin Cities

This page was originally written when I was on the board of the St. Louis Park Historical Society, and appears in a similar form on the Society’s website. I have decided to replicate it on my own site, in order to be able to present it in the first person, and to add my own anecdotes and opinions, as appropriate, to the narrative.

As the title suggests, this page is about diversity, or perhaps the lack of, in the Twin Cities, and people of various races and religions. I don’t purport to include every incident, and I’m afraid I didn’t annotate my sources very well when I first wrote the page several years ago, but as I add information I am mindful to include sources, which I try to restrict to primary vehicles such as newspapers.

It does not include the Jewish Community – you may want to see the companion page, The Jewish Community in St. Louis Park, also on the St. Louis Park Historical Society’s website, for that story.

Please Note:

- The term Ojibwe is used in this document instead of the term Chippewa.

- The term Dakota is used in this document instead of the term Sioux.

Many items come from the St. Louis Park Echo, the newspaper of the St. Louis Park High School, my alma mater.

If you have any additions, corrections, or other issues, please feel free to contact me.

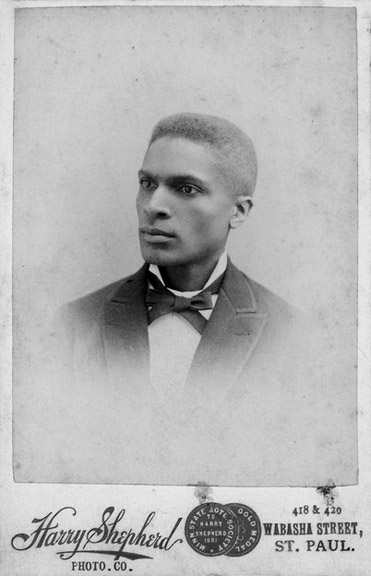

GEORGE BONGO

The first known African-American in Minnesota was said to be Pierre Bonga. A story by Curt Brown in the Star Tribune tells the story of the Bongas:

In the late 1700s, British military Captain Daniel Robertson lived at a fort on Mackinac Island in Lake Michigan. He owned slaves named Jean and Marie-Jeanette Bonga, whose lineage traced from Africa to Jamaica and then the French-speaking West Indies. When Robertson died in 1787, he freed the Bongas. They went into fur trading, as did their son Pierre – George’s father – who traversed northern Minnesota and established a trading post near Pembina, North Dakota, on the Canadian border across from Winnipeg.

George was born near Duluth in 1802, one of five kids of Pierre and his Ojibwe wife, Ogibwayquay. Pierre was successful enough to send his children to school in Montreal, where George mastered French and learned writing skills…

George wrote letters to government leaders alerting them to corruption among the white Indian agents, according to Barry Babcock, a Bemidji-area historian writing a book about Bongo. He helped lead Michigan Territory Governor Lewis Cass’s 1820 Exploration that tried, but failed to find the source of the Mississippi River. When Bongo was 65, he helped negotiate the treaty that established the White Earth Indian Reservation.

George was a fur trader, translator, canoe guide, and storyteller. He stood 6′ 6″ and was famous for singing Voyageur songs while carrying hundreds of pounds of pelts and goods through northern Minnesota’s swampy, mosquito-thick portage trails. In the 1820s and ’30s he served as a guide and fur trader for the American Fur Co. When beaver trapping diminished in 1842, he ran a lodge on Leech Lake. In 1850, he was one of only 14 black people counted in the Minnesota Territorial Census. George Bonga died in 1880 at age 78.

1820

In 1820 the Missouri Compromise banned slavery in the Louisiana Territory north of the southern border of Missouri.

1823

The first African-Americans to come to Minnesota arrived as the slaves of Major Lawrence Taliaferro, who came to Fort Snelling on May 2, 1823. He sold some of the slaves to his friends at the Fort and freed the rest. The slaves of other officers came as well.

1849

When Minnesota became a Territory in 1849, a census recorded 40 free blacks, 30 of which lived in St. Paul. Maria Haynes was the only black resident living in present-day Minneapolis. They were prohibited from voting on congressional, territorial, county, and precinct elections. In 1851 the ban was extended to village elections and in 1853 to town elections.

1850

The 1850 Minnesota Territorial Census counted 14 black people.

1851

In 1851 the US Government signed treaties with the Dakota at Traverse des Sioux and Mendota, opening up southwestern Minnesota to white settlers.

1854

The Territorial legislature considered a bill in 1854 that required African-American residents to post a bond of $300 to $500 as a “guarantee” of good behavior.

In a move to contest the right of foreigners to vote, the Know Nothing Party proposed a 21-year waiting period before immigrants could become citizens, as opposed to five years. The secretive Know Nothings were formed in 1854 to try to keep Irish Catholics out of the US. The St. Paul Pioneer Press pointed out that 8 of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence were not native-born Americans. The “party” fell apart over the issue of slavery just before the Civil War.

1855

In 1855 the US Government and the Ojibwe signed a treaty in Washington, DC.

1857

DRED SCOTT

Slaves Harriet and Dred Scott came to Minnesota with their owner, a Fort Snelling surgeon named Dr. Emerson, in 1836 [1834]. In 1857 Scott sued for his freedom, since Minnesota was not a slave state, but a far-reaching Supreme Court decision ruled that he could not claim freedom because his owner had a right to his property.

The Minneapolis Spokesman reported that the first group of free blacks arrived in in 1857, when eight families came up the Mississippi River from Missouri, Arkansas, and Illinois and settled just above St. Anthony Falls.

Slaves of southerners who vacationed in Minnesota were residents here in the 1850s and ’60s.

During the constitutional convention in 1857, a compromise restricted suffrage to white males in exchange for Democratic support of a simpler method of amending the constitution in the future.

1860

Although Minnesota was admitted as a free state in 1858, there were those who supported slavery. In March 1860, the Democratic party put forth a bill that would allow slave owners to bring their slaves into Minnesota and keep them here for six months without challenge. That bill was defeated, and Republican Abraham Lincoln roundly defeated Democrat Stephen Douglas that same year.

The 1860 Census reported 13 black people in Hennepin County.

1861

Katharine Luella Smith was thought to be the first black child born in Minneapolis proper, on May 4, 1861. She died on January 29, 1941, at the age of 79. Born of free parents, was educated in Minneapolis public schools and the MacPhail School of Music. She was the chief soprano soloist in the Twin Cities, as well as a pianist, composer, and arranger. “Among the best known songs Mrs. Smith wrote was the successful ‘Let My People Go.’” (Minneapolis Spokesman, January 31, 1941)

1862

The Homestead Act of 1862 offered 160 acres to qualified settlers who agreed to live on and improve the property for five years.

THE DAKOTA WAR

The US – Dakota War broke out on August 17, 1862. On September 6, 1862, Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey sent a telegraph to President Lincoln: “This is not our war, it is a national war … send us 500 horses. … Answer me at once. More than 500 whites have been murdered by Indians.”

By the end of the day, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had created the Department of the Northwest, headquartered in St. Paul. Major General John Pope arrived in St. Paul on September 17, 1862, and wrote of his plans for “exterminating or ruining all the Indians engaged in the late outbreak.” Two days later, Sibley began his march up the Minnesota River valley in search of Little Crow, finding him on September 23, 1862. The Battle of Wood Lake resulted, with the Dakota badly defeated and scattered. Pope vowed to follow them and “utterly exterminate” them. On October 7, 1862, more than 1,600 Dakota prisoners, mostly women and children, were ordered to be moved to Fort Snelling. They arrived at the Fort on November 14, 1862. Franklin Steele, who actually owned the Fort and was renting it to the Government, made a fortune on the scrip issued to the “half breeds.” Another 303 men were marched to Mankato, where 38 of them would be hanged in largest mass hanging in US history. The entire story is told in the article “The Great Treasure of the Fort Snelling Prison Camp,” by William Millikan, in Minnesota History, Spring 2010.

1865

Many black soldiers who had joined the Minnesota regiments came to Fort Snelling for discharge after the Civil War and settled in the St. Anthony Falls black community that had been established in 1857. The Spokesman also says that “There were also barge-loads of Negroes who came to St. Anthony Falls as ‘Contrabands of War’ under the colonization plan of President Abraham Lincoln in which he endeavored to alleviate the distress of homeless freed slaves.”

Also after the Civil War, the advent of railroads facilitated immigration and the establishment of towns along the lines.

1866

THE KLAN, PART 1

The Ku Klux Klan, originally organized as a social group, was formed by former Confederate soldiers in 1866.

1867

By 1867, the black settlement at St. Anthony Falls had grown to about 200 people.

In 1867 the State legislature created the State Board of Immigration to encourage immigration to Minnesota.

1868

Black men, “civilized” Indians, and mixed-bloods over the age of 21 first won the vote in Minnesota on March 6, 1868, after two previous referenda turned it down.

Also in 1868, the Sons of Freedom was formed, open to all African-Americans in the State who needed assistance in jobs and trades, or in maintaining their personal property.

1869

On January 1, 1869, black residents of Minnesota held a convention at Ingersoll Hall in St. Paul to “celebrate the Emancipation of 4,000,000 slaves, and to express… gratitude for the bestowal of the elective franchise to the colored people of this State.”

Also in 1869 the state legislature abolished segregation of Minnesota public schools, which ended a ten-year practice in St. Paul.

1870

The Census reported 109 black people in Minneapolis in 1870, or 0.8 percent of the population.

Locally there were 16 black families that lived in Edina from the end of the Civil War until the late 30s, when they moved to Minneapolis. Many of these were in the Yancey family.

1871

The Civil Rights Act of 1871 ended the first iteration of the Ku Klux Klan.

1880

The black population of Minneapolis in 1880 was 362, or 0.8 percent, according to the Federal Census.

1882

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 attempted to stem the tide of Chinese to the west coast. The U.S. Bureau of Immigration was created in 1891 to enforce the law.

1887

The Spokesman noted that in 1887, Andrew F. Hilyer was the first Negro to graduate from the University of Minnesota.

1888

The Minneapolis Spokesman reported that at one time, Minneapolis had its own all-black Fire Department. Its captain was John W. Cheatham, a former slave who came to Minneapolis when he was eight years old. He was appointed to the Fire Department in 1888, and served as the first and only captain of the special unit.

1889

Fredrick L. McGhee moved to St. Paul in 1889 and became Minnesota’s first black attorney.

From MNOPEDIA, by Kate Roberts:

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Fredrick McGhee was known as one of Minnesota’s most prominent trial lawyers. In 1905, he was one of a group of thirty-two men, led by W. E. B. Du Bois, who founded the Niagara Movement, which called for full civil liberties and an end to racial discrimination.

McGhee’s road to the state’s courtrooms followed an unlikely route. He was born in Mississippi slaves’ quarters in 1861, just months after the Civil War broke out. He and his family made their way to Knoxville, Tennessee, after the war, where Fredrick graduated from college, and then to Chicago, where he worked as a waiter to pay his way through law school. In 1889, he settled in St. Paul, where he became the first African American admitted to practice law in Minnesota.

Had McGhee spent all his time in Minnesota advocating for his clients, his contribution already would have been significant. He was known as a powerful, forceful orator, a formidable presence in the courtroom. But McGhee’s influence didn’t end there. After he converted to Catholicism, he became one of the founders of St. Peter Claver Church, still an important gathering place for St. Paul’s African Americans. He became involved in national politics, first as a Republican and then as a Democrat. And in 1905 he was one of a group of thirty-two men, led by W. E. B. Du Bois, who founded the Niagara Movement, which called for full civil liberties and an end to racial discrimination. The Niagara Movement was the catalyst for the 1909 founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). McGhee founded Minnesota’s first NAACP chapter. Years later, the group’s chairman, Roy Wilkins, recalled that “it was through him that the NAACP reached St. Paul and [our house at] 906 Galtier Street.”

“McGhee was not simply a lawyer,” wrote W. E. B. Du Bois in a 1912 obituary for his friend. “He was a staunch advocate of democracy, and because he knew by bitter experience how his own dark face had served as excuse for discouraging him and discriminating unfairly against him, he became especially an advocate of the rights of colored men.”

1890

THE THREAT OF CATHOLOCISM

On September 29, 1980, Rev. J.J. Faude, rector of the Gethsemane Episcopal Church, preached the third in a series of sermons on the growing danger of Catholicism to a standing room only crowd. His tenet was that Catholics were striving to take over the government of the United States, and lately were showing unusual aggression to achieve this goal. He said that one of their methods was to evangelize inmates of state prisons, not just for their votes, but for their “brute force, with which Romanism sooner or later expects to win the day.” Also, “Let me remind you of the effort to sweep negroes into the Catholic church…” He saw the Catholic religion as a political institution, bent on seeking control as a foreign power in the U.S., “making the pope head of all.” The remedy was to “Quit patronizing those fools, who are trying to make Romanists of your children. Give nothing to Catholic institutions and desist paving the way for them. If there is benevolent work to be done, do it yourself without their agency. Watch closely every move that is made against our liberties, and the government we now own allegiance to.”

But there was optimism in some areas: The Minneapolis Tribune of November 13, 1890, reported, “Barriers of Creed – Rabbi Samuel Marks Thinks a Common Charity is Breaking Them.” On the basis of Jewish and Gentile attendance at the Hebrew Charity Ball, Rabbi Marks opined that “the barriers of creed and doctrine are gradually being torn away.”

The black population of Minneapolis was reported as 1,354, or 0.8 percent, in the 1890 Census.

1891

The U.S. Bureau of Immigration was created, in part to enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

1892

In Minnesota History Magazine, Summer 2008, Iric Nathanson wrote of “African Americans and the 1892 Republican National Convention, Minneapolis.” 1892 was the height of Southern lynching, with 161 black men murdered at the hands of white mobs. On May 31, 1892, the African American population of Minneapolis participated in a national day of fasting and prayer, and 1,000 people gathered at the Labor Temple to “protest the crimes of colored people in the South.” The principal address was delivered by William R. Morris, a local black attorney and community leader. The Minneapolis Tribune reprinted the address, which said, in part:

The Negroes of this country have been at the mercy of certain white citizens, who, goaded by an insane desire for blood and unprovoked prejudice and hatred… have ruthlessly and openly, seemingly without fear of God or man, slaughtered, butchered and murdered them.

In fact, the American people have become so accustomed to those open violations of law that scarcely a passing notice is given them. That such an offense as the butchery of citizens should be allowed to go unpunished.. is simply incomprehensible.

It was a prelude to the Republican National Convention which was held in June 1892. There were 116 black delegates to the convention – about 13 percent. After Reconstruction, African-Americans would be shut out of the political process for decades.

1894

Minnesota’s first Mexican resident was Luis Garzon, a trained oboist and graduate of Mexico City’s Conservatory of Music. He came to play with the Mexican National Band at the Minneapolis Industrial Exposition in 1894 and stayed. His children were the state’s first Mexican-Americans.

1898

John Frank Wheaton (1866-1938) arrived in Minnesota in 1893 and attended the University of Minnesota Law School, becoming its first African American graduate in 1894. He became the first black person elected to the Minnesota State Legislature, elected to the House in 1898 and serving in the 1899-1901 session. After his term in office he moved to New York City and became a prominent civil rights attorney.

1900

The black population in Minneapolis was 1,548, or 0.8 percent, according to the 1900 Census. Of the state’s 1.7 million residents, there were under 5,000 African-Americans, most of whom lived in St. Paul.

In 1900 there were only about 200 Chinese residents in Minnesota.

1901

The Minneapolis Tribune of June 4, 1901, carried the headline:

Colored People Talk of Organizing a Golf Club

The club would be beyond the Minikahda Club toward St. Louis Park. The whimsical article reads:

One day last week Scott Blake went boldly into a sporting goods store and bought a driver. One of Scott’s golfing patrons had told him that the first essential in the matter of clubs was a driver. On the same day another colored dignitary purchased a lofter. That evening the two enthusiasts struck out for open country and lost four new golf balls in something under an hour, but on the way back down town both these new made golfers were as happy as clams, Scott because he had drive his first ball so far that it landed beyond human ken, and the other man because he had biffed the such a crack with his lofter that it soared a good hundred feet in the air and landed within 15 feet of the starting point.

When the tidings of this initial success reached the colored community there was much excitement. To be sure, Blake and the other man had stolen a march in being the first out, but there was nothing to prevent the rest getting into the game with customary enthusiasm. Charles Britton and Howard Phillips bought a full set of clubs on the following morning and ever since there has been a rush for golfing outfits by the colored folks of the locality.

“I’ve been thinking of taking up golf for a long time,” said Scott Blake. “Some of the people who play the game have told me that it was the best anti-fat remedy in the market, and the only difficulty has been in the matter of a course. The best golf territory in this part of the country has already been annexed and we have had to do some searching to find suitable links. I think that before long we shall be able to close a deal for the use of land that will give us a very good nine-hole course, and when the deal is made you will see some fun.”

1903

The assassination of President William McKinley by an anarchist in 1901 led to the Anarchist Exclusion Act in 1903.

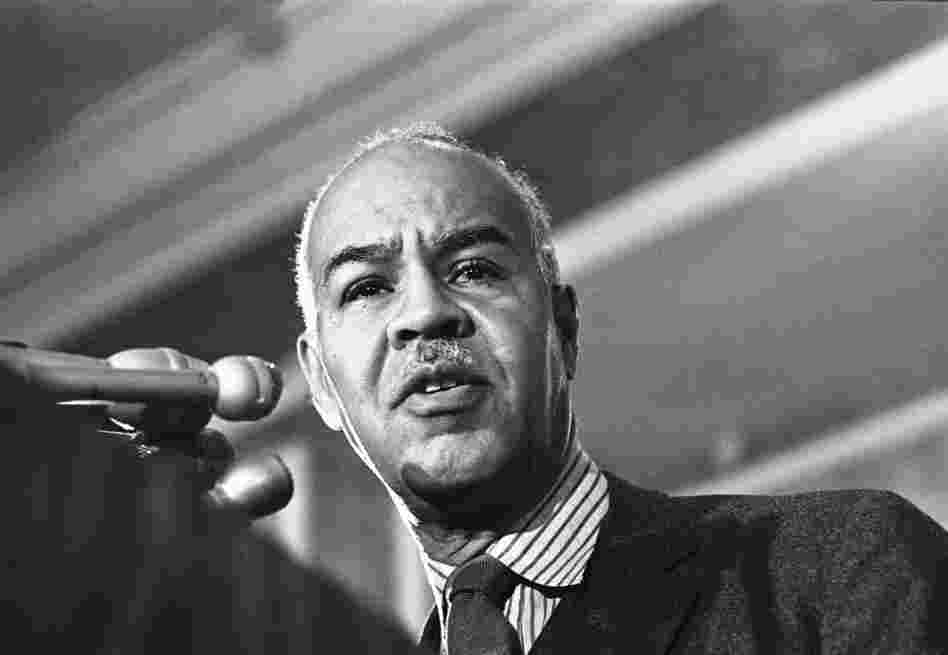

1905

Roy Wilkins, born in Mississippi in 1901, had moved to St. Louis as a child. When his mother died when he was 4, his father sent him to St. Paul to live with his aunt and uncle. He attended Whittier School, Mechanic Arts High School, and the U of M, majoring in Sociology and Journalism. To pay his tuition he worked as a caddie, railroad waiter, and in a slaughterhouse. While at the U he became the first black reporter at the Minnesota Daily. He went on to work for the St. Paul Appeal, a black community newspaper in St. Paul. On graduation in 1923 he left Minnesota for good. He tok an editor’s job at the Kansas City Call and then joined the NAACP’s national staff in New York in 1931. , going on to become the head of the national NAACP from 1955 to 1977. He died in 1981, and in 1985, the St. Paul Auditorium was renamed the Roy Wilkins Arena in his honor. (Curt Brown, Minneapolis Tribune, April 2, 2015)

1907

In 1907 Congress established the Dillingham Commission to investigate the impact of immigration on the U.S. The 42-volume report favored northern Europeans and resulted in quotas on immigrants from southern and eastern Europe in the 1920s.

Mexican migrant workers were known to be in Minnesota as early as 1907 to work in the sugar beet farms. Most returned south for the winter. (St. Louis Park’s sugar beet factory burned down in 1905.)

1910

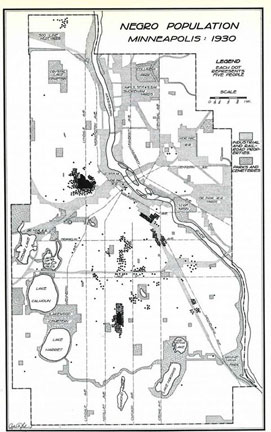

By 1910 the black community in Minneapolis was beginning to move from the Seven Corners area into the North Side, already starting to be vacated by the Jewish community.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) estabished its national office in New York City in 1910.

The 1910 Census reported 2,592 black citizens in Minneapolis (0.9 percent of the population).

1912

In an interview in 1995, Tela Burt, the son of a slave, told Randy Furst of the Minneapolis Star Tribune that

discrimination against blacks was not so bad when he moved to Minneapolis in 1912. “There weren’t enough of us to bother with.” (July 8, 1995)

1914

The Minneapolis branch of the NAACP was founded in 1914. The same year, J. E. Spingarn, the chairman of the national board, came to Minneapolis to preach that whites and blacks should band together to seek rights for blacks. Spingarn was white, as was his audience. The first president of the Minneapolis chapter was Samuel N. Deinard, a rabbi. The group was conceived as a multiracial organization, and blacks and Jews both felt discrimination (and lived in the worst parts of the city). The St. Paul branch had been established in 1913. (Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 8, 1995)

1915

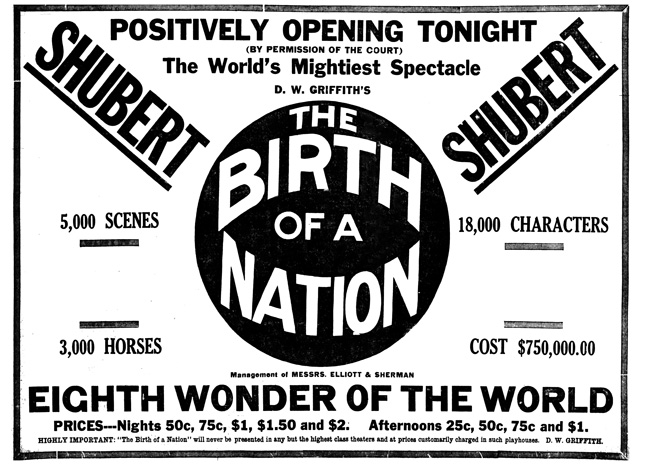

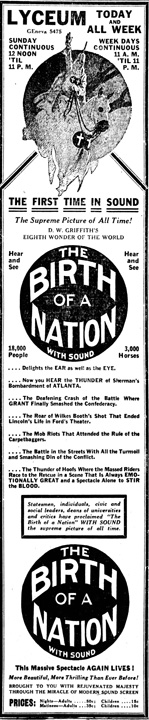

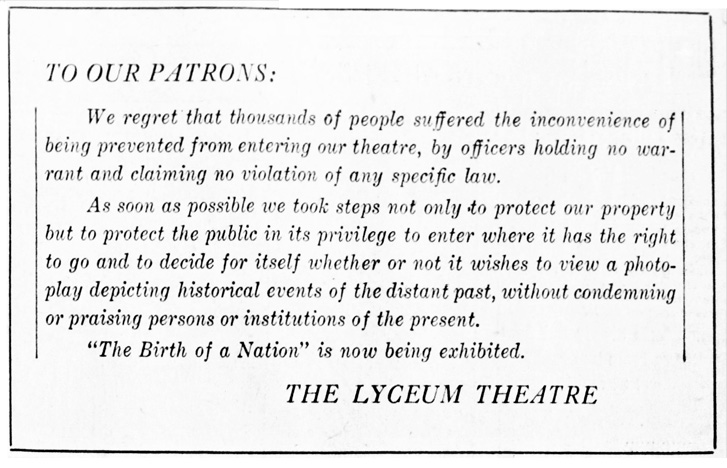

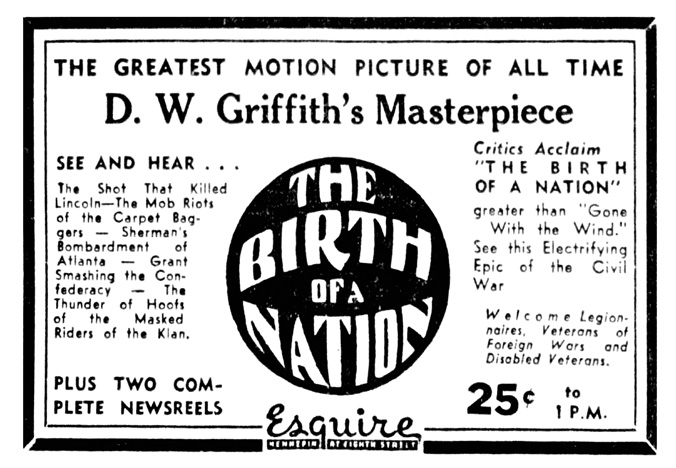

BIRTH OF A NATION, PART 1

D.W. Griffith’s epic 3-hour silent film “Birth of a Nation” came to the Shubert Theater in Minneapolis in October 1915, with controversy right on its heels. The previous April, Mayor Nye had banned the film from being shown, despite the fact that the Superintendent of Schools approved it as educational for school children. (Tribune, October 17, 1915) Its depiction of the Civil War, and especially of the Reconstruction period, with white men playing former slaves in black face, was horrifying, with people leaving the theater wondering, “could that really be true?” The film depicted the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and their role as defenders of Southern womanhood.

Despite the Mayor’s ban, reiterated twice in October 1915, A. G. Bainbridge, Jr., the manager of the Shubert, booked the film to begin showing on October 31 “for an infinite stay.” On October 27, it was shown to a private audience of 1,000 invited guests, including a “jury” of 50 appointed by Nye to give him their opinion of the film. (Tribune, October 28, 1915)

Nye threatened to revoke the theater’s license if it didn’t stop showing the film. Meanwhile, overflow crowds came to see the film, as they did all over the country. (It had been shown in St. Paul on October 23.) The theater filed and injunction against the Mayor, and the issue went to court. (Tribune, October 31, November 2, 1915)

After court hearings, Judge Steele determined that the Mayor did have the power, after a hearing, to revoke the theater’s license. Bainbridge stopped showing the film on November 10, 1915, to avoid losing his license. He said that he had shown it 21 times to 30,000 people without any trouble, and could not understand the Mayor’s concerns. (Tribune, November 14, 1915)

In St. Paul, the city comission revoked the license for the theater showing the film there on November 9, on the grounds of a violation of promises made. (Tribune, November 10, 1915)

The influx of Slavic immigrants into Northeast Minneapolis created the need for a settlement house, in this case the North East Neighborhood House in 1915.

1916

In 1916 the first permanent Mexican-American settlement was established on St. Paul’s west side. Residents formed the Sociedad Anahuac, with the purpose of promoting civic, social and religious activities of Mexicans and Chicanos.

1917

During World War I, blacks were encouraged to come north to work in the factories, but with the return of the servicemen, were considered “loathsome competition,” according to historian Wyn C. Wade.

THE MINNESOTA COMMISSION OF PUBLIC SAFETY

From a MNOPEDIA article written by Matt Reicher:

On March 31, 1917, State Senator George H. Sullivan of Stillwater called for the formation of a seven-member commission to be led by Governor Joseph A. A. Burnquist. The group was to be given broad powers to act to ensure public safety in wartime. Only the laws specified in both the state and federal constitutions limited it.

The U.S. entered World War I on April 6, 1917. Minnesota legislators worked quickly to pass war-related laws before the end of their spring session. As a result, the Sullivan bill saw very little debate. It passed both houses and was signed into law by Burnquist on April 16, 1917. The MCPS took control of many of the state’s regulatory, public safety, and military functions.

Throughout its tenure the MCPS provided useful services. It distributed food, controlled the prices of goods, and conserved fuel. However, it is best known for its use of secret surveillance, intimidation, and other extreme tactics in the name of protecting Minnesota’s citizens.

Ensuring clear-cut loyalty to America eventually overtook the MCPS’s other efforts. Commissioners regarded any lack of patriotism as rebellion. Political beliefs were irrelevant. Governor Burnquist maintained that there were only two parties during the war: “loyal” and “disloyal.” He and the MCPS praised the former and tried to eliminate the latter.

The MCPS scrutinized the state’s immigrant population. It targeted German Americans, considering them suspicious. Loyalty to the Kaiser, the MCPS claimed, could inspire those with German heritage to sabotage the U.S. war effort. They issued orders in 1917 obligating Minnesota schoolteachers to instruct their students exclusively in English. In 1918 they required non-citizens to register their property and report family data.

The Nonpartisan League (NPL) established offices in Minnesota in 1917. The populist advocacy group sought to give farmers better financial control over the products they needed to do business. In the eyes of the MCPS, this made them a “menace” bent on toppling the state’s political and industrial status quo. Rather than engage NPL members on the merits of their views, the MCPS instead tried to silence them.

Lacking the legal power to stop the NPL outright, the MCPS denounced them as un-patriotic. They tacitly encouraged communities to shut down local NPL meetings. In the 1918 Republican gubernatorial primary, the MCPS promoted Burnquist’s reelection campaign. NPL candidate Charles Lindbergh Sr. faced resistance and even violence from MCPS-allied protesters at many of his campaign stops.

The primary Minnesota chapter of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was based in downtown Minneapolis during this time. Trying to take advantage of a labor shortage during the war, they pushed for higher wages, shorter hours, and union recognition. Their actions drew the suspicion of the MCPS, which worked to end labor disturbances across the state. The Commission worked to keep the IWW from assembling. They closed many Minneapolis saloons—key IWW meeting spaces—and passed vagrancy ordinances for other meeting areas.

In the summer of 1917, the MCPS and other groups pushed the Justice Department to take action. On September 5, 1917, federal officials raided IWW offices in Minneapolis, Duluth, and Iron Range towns. This led to the arrest of many of the group’s leaders. Soon after, the MCPS advanced a status-quo resolution that denied employees statewide the right to unionize for the length of the war.

World War I ended on November 11, 1918. The MCPS voided its orders in mid-January 1919, and waited for instructions from the legislature. On April 14, 1919, a House bill calling for the abolition of the MCPS passed 107-12. The Senate voted to keep the Commission. However, while officially still in force until December of 1920, the MCPS never returned to power.

1918

The Federal Alien Registration Act required all aliens to register, to declare their holdings, and explain why they had not become citizens.

Between 1918 and 1919, 136 black people were lynched in America, including women, children, and Veterans in uniform.

1919

A 1919 state law prohibited restrictive covenants on the basis of religious faith or creed but not race.

Tela Burt, the son of a slave, reported that

after World War I, blacks flowed into the city and discrimination increased as whites campaigned to keep them out of their neighborhoods, and restaurants became white-only. (Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 8, 1995)

He also said that the Minneapolis NAACP was largely inactive in the 1910s and ’20s.

The International Institute of Minnesota was founded in 1919 to provide services to immigrants from Northern Europe.

1920

In Minneapolis, the 1920 Census showed a black population of 3,927, reaching 1 percent for the first time

LYNCHING IN DULUTH

On June 15, 1920, black carnival workers Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, aged 19 and 20, were accused of raping a young white woman in a field just behind the circus tents while the carnival was in Duluth. Racial tensions were high after U.S. Steel had brought in black field hands from the South to break a strike. A mob of more than 5,000 whites stormed up Superior Street, breached the jail, and lynched three of the suspects, hanging them from a lamp post. No one was convicted for the crime.

1921

THE KLAN, PART 2

The showing of “Birth of a Nation” in 1915 brought on the resurgence of the of the Ku Klux Klan, particularly in the South. By the 1920s, one third of its membership was from the Midwest. But while the target of the Klan in the South were the former slaves, in the Midwest, where the black population was less than 1 percent, the target was Catholics and recent immigrants, particularly from non-Scandinavian countries. And even so, according to historian Richard K. Tucker, the organization appealed to people who were not filled with the urge to lynch Catholics and foreigners but regular people who were “caught up in a rush of nationalism, nativism, and the perceived need for self-preservation.” The Klan in Minnesota was very different from the Klan in Georgia.

In August 1921 North Star Klan No. 2 came to Minneapolis, holding meetings at Olivet Methodist Church on East 26th Street and at Foss Memorial Church at the corner of Fremont and 18th Ave. No.

Minnesota passed the nation’s first anti-lynching law on April 18, 1921. The bill was authored by Nellie Griswold Francis, president of the Minnesota State Federation of Colored Women. The law imposed a $7,500 fine on perpetrators and provided for suspensions of police officers who failed to protect prisoners from mobs.

The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 set limits on the number of people of all nationalities allowed to immigrate in accordance with the number already in the country.

1922

THE MASONIC CONNECTION

The Masonic Observer, newsletter of the Minneapolis Masons, was first published in 1911. By 1919 it was difficult to distinguish from the Klan newspapers for its anti-Catholic rhetoric, even opining on the Catholic/Protestant clashes in Ireland. I have personally read hard copies of these newsletters from September 30, 1919 to August 30, 1924.

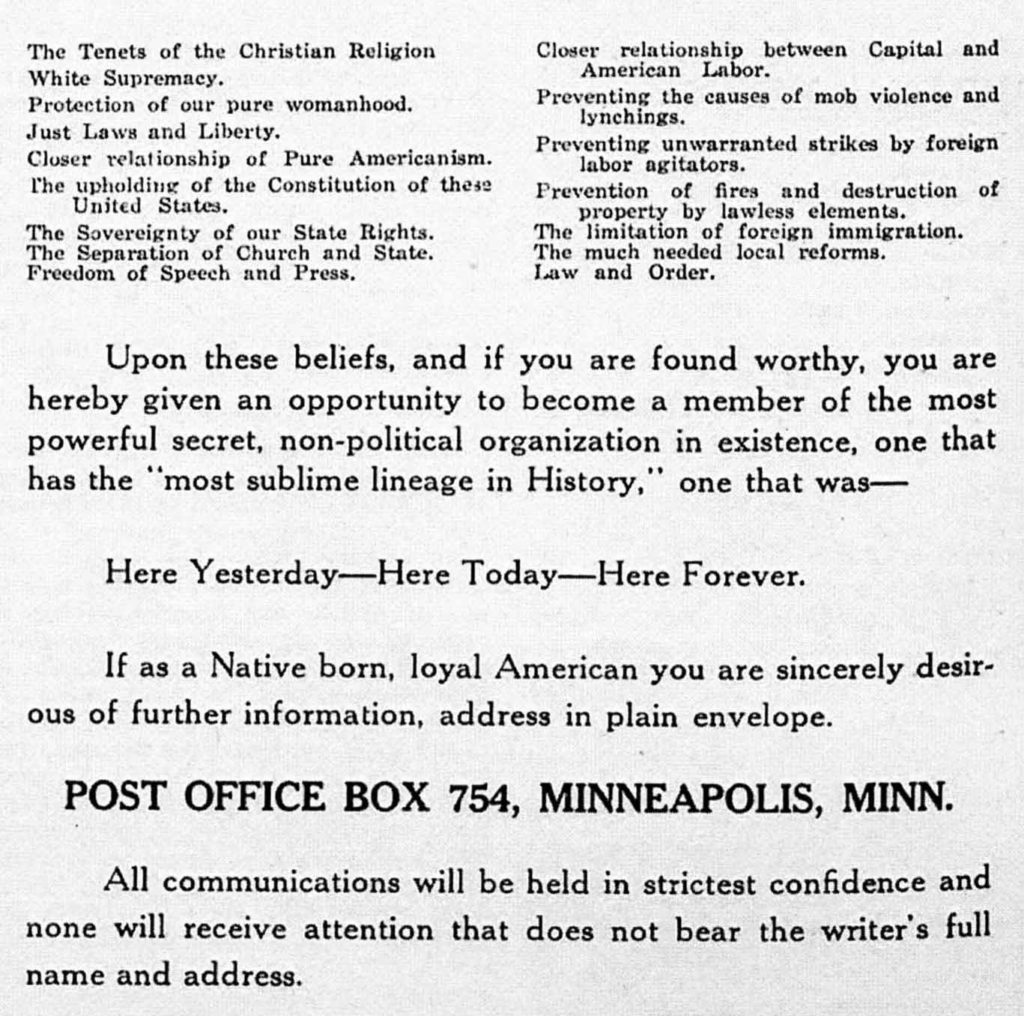

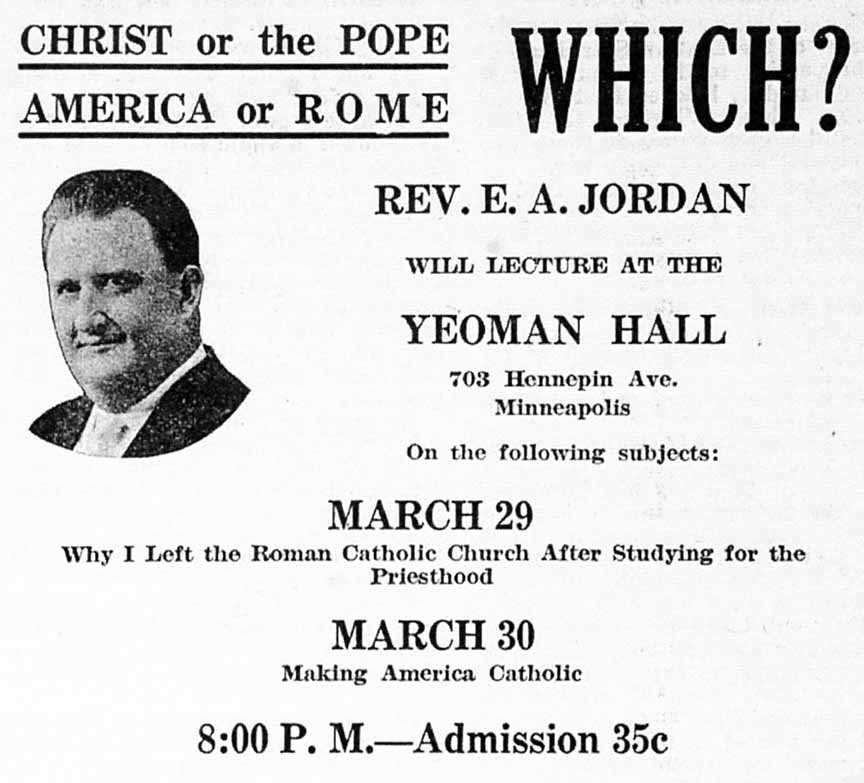

The relationship between the Masons and the Ku Klux Klan began to be seen in 1922. The advertisement below appeared in the Masonic Observer in March 1922.

The ad came with this Note:

The above is a paid advertisement, accepted by the Masonic Observer on the same terms as all other advertising. The Ku Klux Klan is not endorsed either by the Masons of Minnesota or the Masonic Observer, neither is it condemned. We consider our readers to be of higher than average intelligence, fully competent to judge for themselves the merits, or lack of merit, of the organization running this advertisement. — Ed.

DISTURBANCE ON SIXTH AVE. NO.

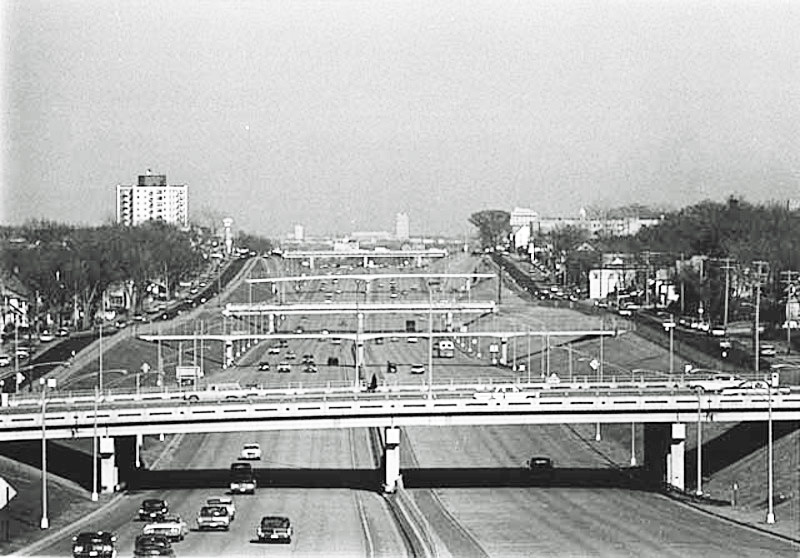

Sixth Ave. North, the black entertainment district for many years until wiped out by Highway 55, was the scene of some acrimony between residents and the police on June 20, 1922.

The Tribune I

The Minneapolis Tribune of June 21, 1922, had this alarming headline:

Armed Negro Holds Crowd of 500 at Bay: Battles Patrolman, Steals His Gun, Threatens Spectators

The article reported that the day started with a crowd gathering as two policemen had trouble arresting four Negroes for disorderly conduct. Another crowd formed an hour later.

That night, yet another incident occurred in the same area. The Tribune‘s account said that police officer George H. McNamee was attempting to arrest a Negro man for “disorderly conduct after complaints had been received that he had been speaking to white girls.” The man resisted arrest and they began to fight, falling to the ground. McNamee got off four rounds, but failed to hit the man. The man grabbed the gun and McNamee “lay in the street while the Negro constantly threatened to shoot him if he moved.” The man backed away, keeping a crowd of 500 people at bay, and made his escape, running west on 6th Ave. toward Colfax. The crowd “refused to help McNamee, although they did not openly hoot him.” A “gun squad” searched for the perpetrator but didn’t find him.

The incident caused the police to take immediate action to end simmering race troubles which have arisen in that district recently. Several Negro clubs were ordered closed later in the evening and an added force of police were assigned to patrol the district. No serious troubles have occurred so far, but police say the race feeling there is such as to warrant precautionary measures.

The Tribune II

On June 23, 1922, a group of citizens wrote to the Tribune to refute its account of what happened.

The fundamental facts of the case were erroneous, the whole account exaggerated. Such accounts as this only cause friction and agitation which eventually culminate in race riots in which innocent as well as guilty suffer. This affair was quite uncalled for. There are eye-witnesses who can refute the statements which you made. It is not quite fair to members of either race if this is not corrected. The Negro and white citizens live in comparative harmony in this locality.

The trouble took place on Aldrich and Sixth avenue. a colored boy was sitting on a railing outside of the drug store, talking to a friend, when an officer of the law approached him, asked him what he was doing here. The boy answered, “sitting here talking.” He then asked the boy where he worked when he answered on the East side, the officer cursed him in a brusque manner. The boy got down off the rail, the officer hit him with his club. The boy told him not to do this and then he grabbed the boy by the collar, attacking him, they fell to the ground. Then the officer drew his revolver. When the boy saw this he became frightened and grabbed the officer’s hand with the gun just in time to avoid being shot. The officer of the law, however, fired four shots. The boy took the guy away from him then and jumped up. The boyed backed away and when the officer, realizing that he had little chance without his gun, disappeared around the corder. The boy then ran down Aldrich Avenue.

During this whole affair there were hardly over a dozen people collected, and not over two hundred collected afterward. There has been no racial disturbance. Below are names of prominent citizens of both races who are willing verify the above statements. An officer of the law should feel it is his personal responsibility to keep all disturbances down and not let himself be the instrument of agitation.

The Bulletin

A different take on the incident appeared in the June 24, 1922, issue of the Northwestern Bulletin, a black newspaper:

Crowd of 500 see Cop Get Worst of Struggle For Gun

Negro Refuses to be Bullied by White Policeman; Takes Cop’s Gun in Fight Then Escapes.

Encounter Marked 3rd Clash Within 24 Hours

Mill City Police Take Steps to End Simmering Race Troubles in 6 Ave. N District

The Bulletin said that the man and a friend had been sitting on a railing at 6th and Aldrich when a policeman came up and ordered them to move on. When the men failed to comply, the policeman struck one of the men with his club and a struggle ensued. The policeman reached for his gun and fired four shots; the man managed to twist the gun and avoid getting shot. The man ended up with the gun, backed away, and ran up Aldrich Ave. toward Fifth Ave. N.

The Bulletin described the other two events differently from the Journal. The first was when police tried to break up a crowd of Negroes at Lyndale Place and Sixth Ave. No. Four men were arrested for disorderly conduct and several others were badly beaten. An hour later police broke up another crowd and closed all Negro clubs.

A committe of citizens has been formed to investigate conditions and ascertain the complaint that Negroes have been speaking to white girls and otherwise conducting themselves in a disorderly manner in that district.

THE KLAN REVEALS ITSELF

The Klan made its first public appearance on September 7, 1922. The next day the St. Paul Daily News gave this report, reproduced in full:

Ghostly Garbed Forms Gather on Knoll Near City

Strong Organization of Invisible Empire in St. Paul and Minneapolis Revealed – Principles Denounce Lawlessness

Daily News Man Taken to Scene in Closed Car

The Ku Klux Klan organized with more than a thousand members in St. Paul and Minneapolis last night. Headed by the fiery cross and robed in the flowing white habiliments of the invisible empire – uniforms surmounted by high-peaked headdress – Knights of the Ku Klux Klan marched 1,000 strong to a field on the outskirts of St. Paul. It was the first active appearance of the organization locally, although, according to klan members, the St. Paul and Minneapolis klans, now numbering over a thousand, have been in existence for more than a year.

On a knoll south of St. Paul, under most ghostlike conditions, an impressive ceremonial, led by the king kleagle of Minnesota, North and South Dakota, concluded early today with the initiation of a class of more than 100. The purpose of the Twin City klan is similar to those elsewhere, the king kleagle told the candidates:

-

- To uphold true Americanism.

- To combat the foreign elements.

- To keep the United States first in the galaxy of nations.

The tenets of the klan forbid lawlessness and offer assistance in the suppression of crime, the kleagle said. He further stressed the vows to uphold the sanctity of the home and American womanhood. A Daily News reporter was one of only two outsiders who witnessed the initiation, although outside of hearing distance of the ritual.

Pursuant to a mysterious invitation, the reporter waited at Lake st. and Calhoun Boulevard, Minneapolis, until 9 pm, when he was met by a closed car. The machine passed outside the city and into the open country. It stopped after an hour near an open knoll south of St. Paul. A solid mass of white figures greeted the visitor.

A moment later electric torches flickered and a score of horsemen dashed up. The visitors were met by the horsemen and escorted into the center of a semicircle made up of several hundred automobiles. In the center of the circle stood a blazing cross. Ahead of it was an American flag. The only other figure in the circle was an altar. On it lay a draped flag, and open Bible and an unsheathed sword. “I am the king kleagle,” said a solemn voice.

“We are here to protect that,” the marked figure garbed in a flowing robe surmounted by an elaborate headdress, said as he pointed to the flag. A chorus of lusty cheers arose. “This is our altar,” the supreme knight continued – “the draped flag, the sword and the open Bible. It is open to the 12th chapter of Romans. Read it. It expresses our sentiments, our purposes and belief.” Following these words the visitors were escorted several hundred yards away where they would be able to witness the initiation, but would be unable to hear the ritual.

Before the initiation began the visitors were warned not to attempt to recognize any of the knights, nor to take any notes, or attempt to determine their location. The King Kleagle raised his hands to the altar and the initiation began. For more than an hour a steady stream of white figures passed by the altar. But one man was taken out of the line. “Take him out,” a loud voice ordered. Then the initiation was resumed.

When the initiation neared its close two horsemen drew up and instructed the visitors to prepare to leave. “It is time to unmask and you must leave,” they were told. A closed car, curtained in on all sides, drove up and the visitors entered. Within an hour the car stopped at Hennepin ave. and Calhoun boulevard, the starting place. The visitors stepped out and the machine drove away.

The Northwestern Bulletin, a black weekly newspaper, reported on the event in its issue of September 16, 1922. (Although the issue was dated September 16 and refers to “last Thursday,” in all probability the event was the one on Thursday, September 7.)

Believe it or not, they’re here!

The Klu Klux Klan held a weird meeting last Thursday night in a neck of the woods at Cedar Lake, near Minneapolis, for the purpose of initiating 100 new klansmen into the membership of the Knights of the Invisible Empire. The meeting while only slightly attended served to advertise the organization’s presence in the Twin Cities.

The services, it is reported, were conducted in practically the same manner they have been advertised heretofore – the fiery cross, the white robed klansmen, white-robed horses and horsemen. Standing before the fiery emblem of the klan, the head klansmen rehearsed the principle of the klan which everybody knows are anti-Negro, anti-catholic, anti-foreigner, in other words, anti-American. To these principles, it is understood nearly 100 new members from the Twin Cities were sworn into the Minnesota legion in the far reach arm of the Invisible Empire.

Klan officials are reported as saying the membership of the organization … total 1,000. They also claim that they have been in existence here for several months but last Thursday night’s meeting was the first meeting here at which outsiders have been allowed to be present.

The publication of the story of the klan’s presence in St. Paul and Minneapolis has caused little or no anxiety here.

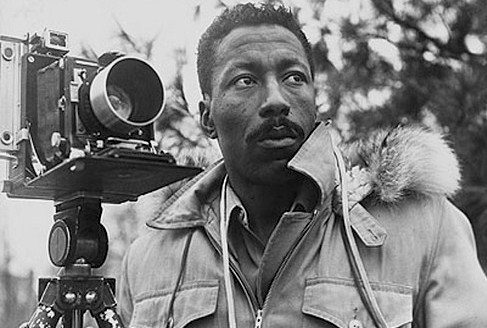

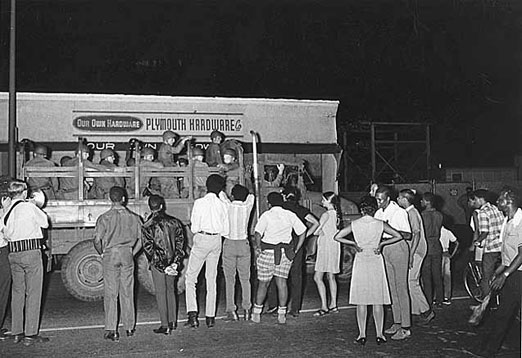

The photo above accompanied both articles with the caption, “A meeting of the inner circles of Klansmen preceded the organization of the secret order. The photograph was snapped with permission of the K. K. K. officials.

KLAN LOCKED OUT

On September 26, 1922, a talk had been scheduled at the Minneapolis Auditorium by Dr. C. Lewis Fowler, Klan official from Atlanta, speaker from the American Educational Foundation, and author of The Ku Klux Klan, Its Origin, Meaning and Scope of Operation. When Fowler arrived, the hall was dark, the doors were locked, and no one had the keys – something about some rental provision not having been met.

The Northwestern Bulletin (September 30, 1922) reported, “Somebody erected a gas jet in the alley southeast of the Auditorium. Dr. Fowler’s driver ran his automobile into the alley to provide a rostrum and the speech was delivered. Dr. Fowler’s address consisted chiefly of an attack on the Catholic religion, the Jews and Colored people.” The Bulletin reported that 3,000 people attended, and “Only the white robes were lacking to give the meeting the traditional Klan atmosphere.”

Several committees of citizens protested the proposed meeting of the klan at the Minneapolis Auditorium and the action of the officials in preventing the meeting is regarded as the first move to put an end to the klan activities here.

The same issue of the Northwestern Bulletin included an editorial entitled “We Must Fight Them.” The strongly-worded piece stated, in part,

The denial of the use of the Minneapolis Auditorium for the purpose of holding a meeting of Ku Klux Klan and their sympathizers last Tuesday night, certainly tends to show that the invasion of the Knights of the Invisible Empire into this field will meet with a cold shoulder.

Now that the K. K. K.’s are among us, we must organize, Negroes, Jews and Catholics, to oust these outlaws. We must be there to fight them at every turn for there is not room here for a government and a klan, too. We must not tolerate these riders of the night.

1923

DR. DIGHT AND EUGENICS

Charles Fremont Dight helped found the Minnesota Eugenics Society in 1923 and began to campaign at the Minnesota Legislature for a sterilization law. In a letter to the editor of the Minneapolis Morning Tribune dated March 19, 1921, he responded to an article about “incorrigibles” with this advice:

This country for many years has been the dumping ground for inferior people from Europe. This accounts in part for our excess of incorrigibles. It is estimated that from 6 to 7 per cent of the immigrants who have recently been arriving are feeble-minded. From 1900 to 1910, 8,500,000 immigrants came here. A United States health authority says that probably only 5 per cent of the mentally deficient were detected and kept out. In 1910 at one of our ports where 1,483 immigrants certified by the inspecting surgeons as unfit to land because of serious mental or physical defects 1,370 were landed anyway.

In view of the grave situation it is almost criminal to continue to absorb European undesirables. To get rid of the over-load of mentally sub-normal people which we already have is the big problem. To do this requires three things:

First, that state and national pedigrees of families who are free from, and those not free from serious inheritable defects be assembled and made available as an aid to better marriage matings. This work is now being done by the Carnegie Institute, aided by institutions in various states.

Second, that adults who are mentally sub-normal and obviously unfit shall be prevented from reproducing, either by segregating them, of course under good conditions, during their reproductive period, or by performing on them the operation of vasectomy. This operation is now legalized in 12 states. It is simple and safe, and when it and its effects are explained to persons on whom it is proposed many of them welcome it.

Third, that young people be instructed on the great facts of heredity that have been discovered in recent years, and on the vital importance to themselves and their children of shunning marriage with one who is socially unfit.

By these means the incorrigibles will disappear. Industrial democracy will be established by good human stock that will appreciate and maintain it. A better era for mankind will be ushered in. – Dr. C.F. Dight.

The local Masons, at least those who were publishing the organization’s newsletter, were becoming more and more virulent anti-Catholics. The ad below was published in the National Observer, which succeeded the Masonic Observer on February 10, 1923.

In June 1923, the National Observer warned Masonic women to stay away from the newly-formed Auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan – “at least for now.” It was also reprinting KKK addresses by leaders in Texas.

The Twin Cities Urban League was founded in 1923, despite fears of the Chamber of Commerce that it would only encourage more black migration to the area. In 1938 the organization split and there were separate Urban Leagues for Minneapolis and St. Paul.

SHERIFF EARLE BROWN

In her book The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota, Elizabeth Dorsey Hatle writes that longtime Hennepin County Sheriff Earle Brown of Brooklyn Center:

was accused of and later admitted (to a Minneapolis grand jury in April 1923) to having joined the Minnesota Klan – membership no. 4. Sheriff Brown told the grand jurors that he joined the Klan because he realized that it was becoming a powerful organization, and he wanted, as an officer of the law, to “be on the inside.”

was solicited to join the Klan by a Mr. Henson of Omaha in the detective service of the Bell Telephone company in 1921.

was initiated in the Klan organizer’s room in the Dyckman Hotel a few months before April 1923. The Dyckman Hotel was regularly reported on in the Midway News as being the meeting spot for the Twin Cities Klan activities.

As Sheriff in the 1920s, did nothing during his tenure to stop the Minneapolis Klan chapters from meeting or burning their crosses in Hennepin County.

“Earle Brown candidate for Governor, Republican, is considered a Robbinsdale man, and keeps his fraternal and social relations here although he lives over the line in Brooklyn Center.” (unattributed quote)

First of all, it is important to understand the Klan in Minnesota in 1923. With a population that was less than 1 percent black, it wasn’t the Klan of the South. Instead, the Klan of the Midwest was a nativist, Protestant, virulently anti-Catholic, anti-foreigner, anti-Jewish organization made up of ordinary people who just did not like all the immigrants who were coming to the United States. As Tela Burt reiterated, there were just not enough black people to bother with. That doesn’t make them nice people, but they weren’t out lynching black people.

And if Brown was a Klan member, Hatle does not prove her case. A high school history teacher, she backs up this claim as the “Earle Brown Papers,” four boxes at the Anderson Library at the U of M. She does not cite a particular document in those boxes. I am a big believer in primary documentation, and she does not provide any.

I would also like to point out that it was not illegal to be a member of the Klan. During the 1920s, hundreds of thousands of men were members – perhaps your grandfather – in misguided visions of white, native-born supremacy. The organization fell apart in 1925 in scandal, and even the editor of the newsletter expressed regret that he had been involved. But in the heat of popularity, what they did was march and burn crosses. That is what they did. The Sheriff had no authority or reason (or probably ability) to stop it.

Another puzzling item is that Grand Jury testimony is secret. On April 21, 1923, the Minneapolis Tribune reported that, although another witness had named him as a member of the Klan, Brown declined to make a public statement, citing the secrecy of Grand Jury testimony. How did Hatle get it?

Wikipedia:

Grand jury proceedings are secret. No judge is present; the proceedings are led by a prosecutor; and the defendant has no right to present his case or (in many instances) to be informed of the proceedings at all. While court reporters usually transcribe the proceedings, the records are sealed. The case for such secrecy was unanimously upheld by the Burger Court in Douglas Oil Co. of Cal. v. Petrol Stops Northwest, 441 US 211 (1979) The dissenting opinion was joined by Justices Burger and Stewart but concurred with the Court’s opinion as to the importance and rationale of grand jury secrecy. Writing for the Court, Justice Powell found that “if preindictment proceedings were made public, many prospective witnesses would be hesitant to come forward voluntarily”; “witnesses who appeared before the grand jury would be less likely to testify fully and frankly”; and “there also would be the risk that those about to be indicted would flee, or would try to influence individual grand jurors”. Further, “persons who are accused but exonerated by the grand jury [should] not be held up to public ridicule”.

United States v. Procter & Gamble Co., 356 US 677 (1958), permitted the disclosure of grand jury transcripts under certain restrictions: “a private party seeking to obtain grand jury transcripts must demonstrate that ‘without the transcript a defense would be greatly prejudiced or that without reference to it an injustice would be done’” and must make its requests “with particularity. Further, First Amendment protections generally permit the witnesses summoned by a grand jury to discuss their testimony, although Dennis v. United States, 384 US 855 (1966), found that such public discussion permits release of the transcripts of their actual testimony.

The Jencks Act, 18 U.S.C. § 3500, requires the government to disclose to the defense any statements made by the accused to the grand jury, and, with respect to non-party witnesses, that after a witness has testified on direct examination at trial, any statement made to the grand jury by such witness be disclosed to the defense.

An Earle Brown scholar has read all of his diaries, and has concluded that he probably went to one meeting, consistent with his contention that he did go to check it out.

On April 29, 1923, the Tribune reported a line of questioning in which Brown was asked whether a member of the Klan was a proper person to be a Deputy in his office, and he replied, “No, I do not.” He had fired several Deputies who had been found to be members. “A deputy under me can have no outside interests,” he said.

If Earle Brown was a member of the Klan, I think we deserve better documentation. And if he was a member, we’d have to look at his motives. And if he really was a member, it really doesn’t look like he joined because he hated black people.

KU KLUX KLAN NEWSPAPERS

The following information is based on my reading of all of the available newspapers on microfilm at the Minnesota Historical Society.

VOICE OF THE KNIGHTS OF THE KKK

Voice of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan began publication on February 8, 1923, by the North Star Klan No. 2 of Minneapolis. In its statement of what the organization stood for, the emphasis was on how it was law-abiding. Telling sections are:

The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan is an organization of Native-Born American, White, Gentile, Protestant Citizens, formed to oppose, by all legal means, every lawless element in our country.

Also,

You will find every Bootlegger, Blindpigger, Dive and Resort Keeper, every Dope Seller, every Crook and Criminal in the United States individually and collectively opponents of the Ku Klux Klan, and lined up with these… will be found every Anarchist, every I.W.W., every “Red” Radical, every enemy of the Public Schools, every Servant of a Foreign Pope and every Alien Enemy of our country…”

REMEMBER: Klansmen are not Reds, Radicals, Arson Fiends, Thus and Murderer. They are loyal American Citizens, your own neighbors, the friends you meet and are glad to greet every day. Klansmen eat at your table, regulary transact business with you and attend church with you, where you listen to sermons preached by Klansmen from protestant pulpits all over our land proclaiming the gospel of that Christ who is ever their example. Klansmen are honored men in the communities in which they reside.

The February issue featured a letter to members of the Minnesota State Legislature signed by the “Exalted Cyclops,” and provided a guide to what it stands for, which is freedom of religion, but not for Catholics in politics.

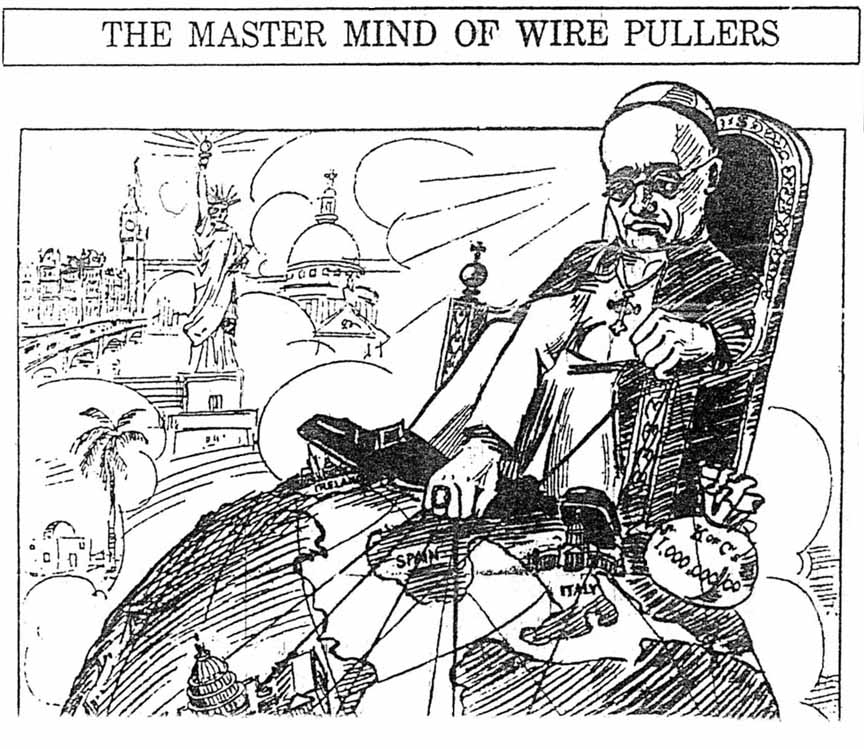

The April 10, 1923, issue made it clear – the screaming headline read “Plot of Rome to Grasp Control of U.S. Bared in Expose of Amazing Documents.” A cartoon shows the Pope sitting on the globe, pulling puppet strings and aided by a bag of money contributed by the Knights of Columbus. Apparently the KKK saw as many Catholics infiltrating the government as McCarthy saw Communists.

CALL OF THE NORTH

The Call of the North came out of St. Paul, edited by P.J. “Twighlight” Orn (real name Peter Sletterdahl). Here are some highlights of the issues available:

Issue 1, July 27, 1923: With a pressing of 10,000 copies, the masthead read “Eternal Vigilance is the Price of Liberty.” The paper had a heavy morality bent, naming as its enemies the “gambler, bootlegger, burglar, libertine, wife beater, dope peddler, crooked politician, Bolshevist, and disloyalist.” Immigration was identified as the “most pressing problem of the hour.” Most of the news was of outstate or out-of-state happenings, but that first issue did report on a meeting held on July 23, 1923, in St. Paul, where a class of candidates was naturalized and a flaming cross could be seen by thousands all over the city. A goal of membership was set for 25,000 by next year.

Issue 2, August 3, 1923: A 28 ft. cross was burned in Washington County on July 30, 1923, a combined effort of St. Paul and Stillwater Klans. It also announced the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, Believing in:

The Tenets of the Christian Religion

White Supremacy

Protection of our Pure American Womanhood

Closer Relationship between Capital and Labor

Preventing unwarranted Strikes by Foreign Labor Agitators

Upholding the Constitution of the United States of America

The Sovereignty of our State Rights

The Promotion of Pure Americanism

Limitation of Foreign Immigration

Education for Worthy American Citizenship

Protection of the Weak and Innocent; Defense of the Helpless

Relief of the Injured and Oppressed, the Suffering and Unfortunate

Freedom of Speech and Press

Public Education

Separation of Church and State

Issue 3, August 10, 1923: This was the first issue with ads. An article railed against Jews in the movies. It also reprinted an article from the St. Paul Dispatch that described a 20 ft. cross burned “on the hill facing Little Bass lake, seven miles north of St. Paul, while at least 100 robed followers of the Ku Klux Klan and perhaps 400 men in civilian clothes held a Klan meeting in the hollow close to the lake.” [Owassa Boulevard runs between Big Bass Lake and Little Bass Lake.] The property was owned by Charles Chapman, a black man. The National Observer reported that the ceremony included a silent tribute to the late President Harding.

Issue 4, August 17, 1923

Issue 5, August 24, 1923: A state convention was announced for October 7, 1923. On August 20, a crowd was naturalized in Ramsey County.

Issue 6, August 31, 1923

THE KKK INITIATION OF AUGUST 31, 1923

Issue 7, September 7, 1923: Issue 7 described the first Klan parade in Minnesota, held in Albert Lea on August 31, 1923. A crowd was naturalized at the county fairgrounds. Rain plagued the proceedings, along with bad roads, which forced the 250-man delegation from Minneapolis to miss the initiation, but they did make the parade. Three 35 ft. crosses were lit.

After a barbeque at the bottom of a sandpit “in a cow pasture outside the city limits on the Jefferson highway near Victory Memorial Drive,” 500 white robed members of the Minneapolis Klan initiated 50 new members. The pasture was patrolled by “ghostly guards who forbade entry to person who could not give the Klan password.” “The road off of the highway leading to the field was jammed with 200 automobiles.” “At the edge of the pit, a small platform had been erected and near it a large cross which, when lighted, attracted the attention of hundreds of motorists.” Peter J. Orn, editor of the Call of the North, was in charge of the initiation ceremony. “Clark F. Gross, acting grand dragon and king of the klan in Minnesota, was in charge of the meeting.” (Minneapolis Journal, September 30, 1923)

On October 6, 1923, the National Observer reported about the initiation in great detail: “the largest class ever initiated at one time by any Klan in Minnesota.” The ceremony took place “in an amphitheatre developed from an abandoned sand pit just outside the limits of Minneapolis, near Victory Memorial Drive.” [Liberty Highway between Minneapolis and Robbinsdale] The men were inducted into the North Star Klan No. 2. The event started with a “genuine old-fashioned southern barbecue, to the accompaniment of one of the best saxophone quartettes in the country. Following this the ritualistic work was completed, while a great fiery cross blazed above the assemblage, and then short addresses were made and special entertainment features witnessed by all.” The entertainment consisted of a wrestling match and a “Swedish dialect specialty.” The article went on to correct misinformation reported by the Minneapolis Journal, and then recapped a speech by a Klansman from Iowa, who railed against the Catholics in his town. At the end of the article was this statement, which made no bones about the relationship between the paper and the Klan: “This is submitted for the benefit of those few well meaning, but misinformed, Americans who still hold that there is no need for an organization like the Ku Klux Klan.”

Issue 8, September 14, 1923

Issue 9, September 21, 1923. This issue reported that the St. Paul Klan met on September 17, and despite the rain, initiated a large class of candidates. 500 attended.

Issue 10, September 28, 1923

Issue 11, October 5, 1923

Issue 12, October 15, 1923. This issue reported on the state convention (Klorero), which began on October 7, 1923. Saturday night featured a “frolic, where St. Paul Klansmen royally entertained their visiting brothers putting on a series of ‘stunts’ that brought continuous uproars of laughter.” Sunday morning revealed that there were 27 fieldworkers in the state. Sunday afternoon featured an inspirational address by the King KlEagle for Minnesota. On Monday a crowd of men were naturalized in Ramsey County despite more rain. The paper reported 500 attendees.

Issue 13, October 24, 1923

Issue 14, October 31, 1923: The Klan had a goal of 10 million members by July 4, 1924. The American Legion declared the Klan UnAmerican.

Issue 15, November 7, 1923: “St. Paul: A Crook’s Haven?”

Issue 16, November 14, 1923: New motto on masthead: “The Voice of Militant Protestantism in the Northwest”

Issue 17, November 21, 1923: A 10 ft. high cross was set up across the street from the St. Paul Cathedral with a sign “Americans join the KKK.” 200 people came and kicked it down.

Issue 18, November 28, 1923

Issue 19, December 5, 1923: This issue pointed out that America’s Founding Fathers were Protestant.

Issue 20, December 12, 1923

KERFOOT VS. THE KLAN

One incident with at least a passing connection to St. Louis Park concerns Dr. Samuel F. Kerfoot, who was, very early in his career, pastor of the St. Louis Park Methodist Church from 1892 to October 1894. From 1912 to 1927 he was the president of Hamline University, where he had graduated in 1889. On December 12, 1923, the Call of the North printed a letter that Kerfoot had written in response to criticism that he had let the National Vigilance Association use his name. He said that his understanding was that the organization was for the conservation of law and legal procedure under the Constitution. This organization apparently also had an interest in fighting to destroy the KKK “which is a matter in which I have only passing interest.” But he was also blunt in stating that he was opposed to the KKK’s “un-American method of covering up their identity and their procedure in frequent cases of taking law into their own hands.” He also called the organization “so radical and un-Christian as to endeavor to develop divisive methods between races and religions.” P.J. Orn, editor of the Call of the North, denied all charges in a letter published next to Kerfoot’s, but what is telling is that he signed his letter “Yours for Protestants that Protest.”

Issue 21, December 19, 1923

Issue 22, December 26, 1923

Issue 23, January 2, 1924

Issue 24, January 9, 1924

Issue 25 (missing)

Issue 26, January 25, 1924

Issue 27, February 1, 1924

Issue 28, February 8, 1924

Issue 29, February 15, 1924

At this point the Call of the North was renamed the Fiery Cross – see 1924.

JACK TRICE

Jack Trice was born in 1902, in Hiram, Ohio, the son of a former Buffalo Soldier. His parents sent him to Cincinnati to live with his uncle and better his educational opportunities. He starred on his high school football team. His coach, Sam Willaman, was hired as head football coach for Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. He asked Trice and a couple of his football teammates to attend the school and play ball there. Trice accepted.

Trice worked hard at Iowa State both academically and physically, cleaning locker rooms to pay for his education. By his sophomore year all the hard work paid off in good grades and making the varsity team. A lot of college conferences did not want Blacks to play in their leagues, so Trice’s first game was an exhibition game.

On October 5, 1923, Iowa State University headed to Minneapolis where they were scheduled to play the Gophers the next day. When they reached the Curtis Hotel, the manager told them no Negro (i.e., Jack Trice) could stay in a room or eat at the restaurant. The team found Trice a place to stay at the Phyllis Wheatley Settlement House. That’s where he wrote the letter that would later be read at his funeral.

On the day of the game, the KKK was at the stadium and there had been a float sponsored by the Klan in the homecoming parade. A man campaigning for the mayor of St. Paul, openly a member of the Klan, was also at the game. Trice was unaware of the danger surrounding him.

Through the first quarter he blocked every play that he could, even though his collar bone was broken on the second play. When Trice was on the field, the U of M players were berating him, calling him racial slurs, kicking and spitting on him. In spite of all this, Trice refused to leave the game.

By the third quarter, Trice was badly injured, lost consciousness, and was rushed to the University of Minnesota Hospital as the Gopher fans mockingly chanted, “So sorry, Ames” over and over again. Minnesota won the game 20 to 17.

A few hours later, after the doctors declared Trice fit to travel, he rode the train with the team back to Ames, even though he was still suffering serious abdominal pains. There he was again rushed to the hospital with internal bleeding. Two days later, Jack Trice died of his game injuries.

Much speculation surrounds the play that resulted in Trice’s death. Many of his teammates said after the fact that he had been targeted throughout the first two quarters because of his skin color. The grandfather of University of Minnesota sports historian Bob Patrin had attended the game and was terribly upset. Patrin said his grandfather told him, “Jack roll-blocked three Gopher players, and after the play the three players start beating and stomping him. Grandfather…knew that those players would kill that Negro football player, and he left the game.”

Trice’s funeral was attended by more than 4,000 people including family, friends, students, faculty, community members, and the Iowa State University president, who read the letter Trice wrote at Phyllis Wheatley. It read:

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life: The honor of my race, family, and self is at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped, I will be trying to do more than my part. On all defensive plays, I must break through the opponents’ line and stop the play in their territory. Beware of mass interference. Fight low, with your eyes open and toward the play. Watch out for crossbucks and reverse end runs. Be on your toes every minute if you expect to make good.

As a result of this incident and Trice’s death, Iowa State University did not renew its contract to play the University of Minnesota. The two teams did not meet again for 65 years.

The playing field in Iowa State’s Cyclone Stadium was named Jack Trice Field in 1975 to honor the school’s first African American athlete and the school’s first athlete to die of injuries sustained during an athletic competition. In response to student demands, the stadium itself was renamed Jack Trice Stadium in 1997, the only such Division I stadium to be named after an African American.

(From a story by Ken Foxworth in the Minneapolis Spokesman-Recorder, February 9, 2020)

THE KLAN’S MAYORAL DEBACLE OF 1923

David Mark Chalmers, in his book The First Century of the Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1965, tells the story of Minneapolis Mayor George E. Leach, who had originally been a conservative, but whose policies raised the ire of the anti-labor Citizens’ Alliance and Committee of Thirteen, an outgrowth of the wartime American Protective League. The Klan turned against him when he:

- Hired a Roman Catholic as his secretary

- Dined with the Knights of Columbus

- Forbade the police to join the Klan

- Launched an investigation into reported Klan activity at the U of M

North Star Klan #2 decided to put their Exalted Cyclops, Roy Miner, up for Mayor, with the platform of stamping out gambling and vice.

Now the problem was to collect proper campaign materials. They found them in the city jail. A woman domiciled there claimed that she had been intimate with the mayor. Candidate Miner went to call upon her, and the Klan printed her story and distributed it about town.

The April 10, 1923 issue of the Voice of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan had included an affidavit from “woman of the underworld,” Gladys Kennedy, that “George E. Leach, Mayor of Minneapolis, has upon three or four occasions visited my house and gone into private rooms with girls of my acquaintance and stayed in the room with them for several hours.”

A grand jury thought that the story was libelous. Farmer-Laborite Floyd B. Olson, on his way to the governor’s mansion, handled the prosecution. The case attracted wide attention outside the state and Klan notables traveled to Minneapolis to witness what they anticipated would be a Klan exoneration and triumph. But such was not to be the case. The Klan’s star witness, on leave from jail, admitted chronic drunkenness and the falseness of her claims of intimacy with Mayor Leach and other prominent men…. The Protestant jury, which included a Methodist minister and several Masons and Shriners, brought back a guilty verdict and the five accused Klansmen went to jail.

Five people were convicted of libel:

- Roy Miner, who served 90 days in the Workhouse

- George S. Silk, Editor of the Hennepin County Enterprise (Hopkins), who printed the libelous edition of the Voice. Silk died in 1924 before his appeal came up.

- Thomas E. Sullivan, who transported the issues of the Voice from Hopkins to Minneapolis

- Shurley Reichert, a University of Minnesota student. He was fined $50, with an option of 30 days in the Workhouse.

- Gladys Kennedy, presumably; although Hatle’s book doesn’t mention her, she was, after all, the one who signed the affidavit that the Mayor had slept with her prostitutes.

Milton Elrod, editor of the Fiery Cross, tried to get the North Star #2 chapter to surrender its charter, but it refused. Elrod pushed another opponent of Leach, former State Senator William Campbell, who denied he was presently a Klansman. Leach won by more than 5,000 votes. Thus ended the Klan as a political power in the state.

The National Observer, mouthpiece of the Minneapolis Masons, continued to strengthen its relationship with the KKK, with headlines such as “Numerical Strength of the Ku Klux Klan” (September 8, 1923); “The Ideals and Inspiration of the Ku Klux Klan” (September 29, 1923); “The Real K.K.K. Becoming Known in Spite of Garbled Press Reports,” (December 8, 1923); “Right and Wrong Activities of the Ku Klux Klan,” (December 29, 1923)

1924

MORE KLAN NEWS

January 2, 1924: The Call of the North used a great deal of newsprint to tell the tale of Turner Starks, who bought a lot on St. Clair Street in the Groveland Park neighborhood of St. Paul in order to build a barber shop. Although the move was objected to in the story in terms of setbacks, zoning, proximity to a school, etc., it consistently referred to “Negro Starks” and placed a lot of blame for the situation on Den E. Lane, a “community organizer” who sold the lot to Starks. The Groveland Park Improvement Association was informed of the excavation for the 15 x 50 ft. building on May 14, 1923, and passed a resolution that read: “Be it resolved that the Groveland Park Improvement Association is unalterably opposed to the erection of a colored barber shop on St. Clair St….” Two emissaries went to present the resolution to Starks at his current barber shop on Grand Ave. After his offer to sell the lot back to them for the outrageous price of $3,000, Starks became angry and used “(oaths too vile to be printed.)” He got a gun and shot one of the men’s hat off. Apparently Starks thought that the Klan was behind the move to bar his barber shop. Eventually Starks pleaded guilty to attempted assault in the second degree, and was sentenced to one year in the state pen. But the sentence was suspended, which really was the crux of the article’s outrage.

Also on January 2, 1924, the Call of the North printed a long editorial, “No Race Settlement Possible.” The piece had three points:

- In the first place, both sides must learn to take people just as they are.

- Then the negro must be considered both as a race and as individuals.

- Finally the negro must be considered, both as to his future development and his present standing. We must try to help the negro to become a better worker and citizen.

THE FIERY CROSS

After 29 issues, the Call of the North changed its name to the Fiery Cross on February 22, 1924. Numbering of issues stayed the same.

Issue 30, February 22, 1924: Tri-State Music Publishers of Memphis placed an ad for a song called the “Ku Klux Blues Fox Trot.” “Sing American Made Music” Apparently this was available in both sheet music and piano roll form.

Issue 31, February 29, 1924

Issue 32, March 7, 1924: The Minneapolis Jewish community was opposed to the “Johnson bill” that proposed a change to the current immigration law. The paper reported that the proposed changes in the formula “would exclude a large number of Jews, Italians, and other peoples that do not assimilate readily.” The language was strong:

For our national life we must prevent this country from becoming the dump-yard of the world; we have no need for the polyglot riff-raff that other nations wish to disgorge. Every American who truly loves the United States should let his congressman know that he wants legislation which will stem the alien tide of undesirables.

On March 8, 1924, the Fiery Cross reported a series of attacks on men selling the organ of the Klan on Hennepin Ave. The trouble started at 5th and Hennepin, and the “anti-Klan mob composed mostly of Jews” moved up the street, getting rowdier and rowdier until the newspaper sellers at 8th Street were beaten up pretty badly.

Issue 33, March 14, 1924

Issue 34, March 21, 1924

Issue 35, March 28, 1924

Issue 36, April 4, 1924

Issue 37, April 11, 1924

Issue 38, April 18, 1924

Issue 39, April 25, 1924

Issue 40, May 2, 1924. Reported that on April 16, 1924, 31 Klansmen from St. Paul traveled to North Branch for a lecture, followed by the burning of a cross “on the other side of the railroad tracks. Four natives and two cows witnessed the spectacular feat.”

Issue 40 also told the sad tale of Harold Prouellett, age four, and Alice Tanner, age six, who disappeared in February 1924. After months with no clues, Mr. Tanner expressed concern that the Klan had assisted the girl’s father, his wife’s ex-husband, in kidnapping the child. The Minnesota Star took up the story, which was emphatically denied by the Fiery Cross in its April 11, 1924, issue. On April 25, the bodies of the children were found in the Mississippi River, proving the Klan theory wrong.

Issue 41, May 9, 1924

Issue 42, May 16, 1924

Issue 43, May 23, 1924

Issue 44, May 30, 1924. This was apparently the last issue of the Fiery Cross.

COUNTRY CLUB

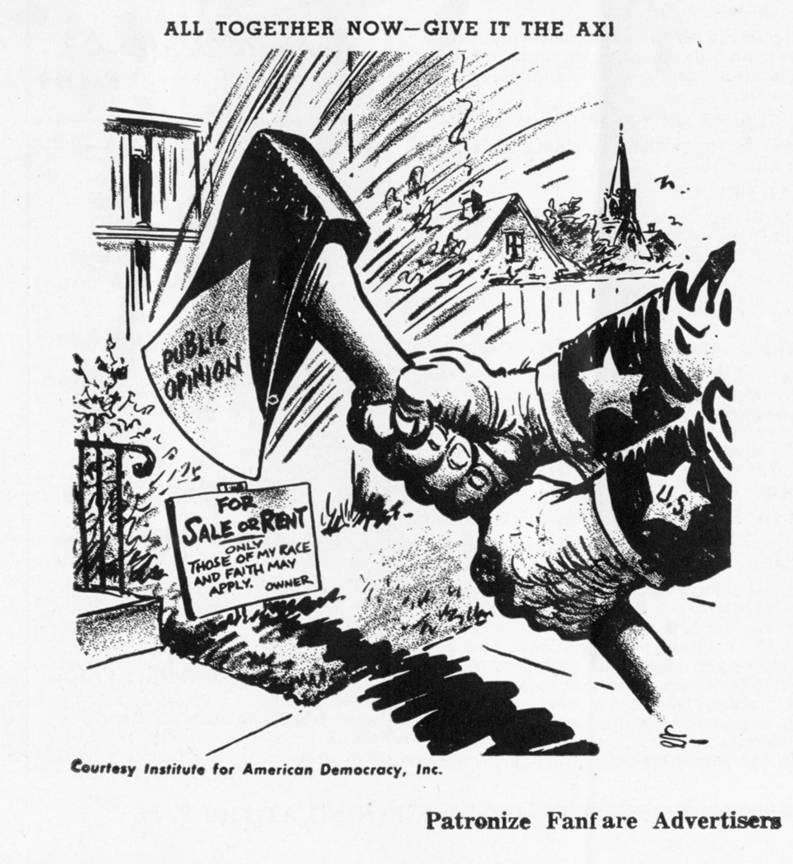

In 1924 the Country Club District of Edina was platted. The subdivision, built by Samuel Thorpe, was based on a similar subdivision in Kansas City and from the first was meant for the higher classes. The first house, sold in June 1924, was located on Browndale Avenue in the heart of the development. By 1927, 200 houses and a golf course had been built. Homebuyers faced many restrictions as to the cost of the houses they built, the kinds of trees they could plant, the animals they could keep, etc. Most notably, occupants were strictly restricted to the “white or Caucasian race.” All restrictions were to expire on or before January 1, 1964, except the one regarding race, which was to remain in force forever. All such race-specific real estate covenants were invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948. Such attitudes contributed to the movement of the Settle, Lucas, and Yancey families, black families that had lived in Edina for generations, to move to Minneapolis.

The Oriental Exclusion Act was enacted in 1924.

The U.S. Border Patrol was created in 1924 to prevent smuggling of illegal substances (Prohibition was in effect) and illegal migrants.

Tela Burt, the son of a slave, reported that

The Ku Klux Klan set up a camp near Anoka about 1924 or 1925. They had a tent and burned a cross. They were after Jews. There weren’t enough Negroes to deal with. (Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 8, 1995)

From 1924 to 1927, St. Paul’s Midway News published a directory of persons who held membership in the Ku Klux Klan, noting that the organization included many men who were also members of fraternal orders such as the Masons and the Shriners. (I do not have a citation for this.)