The King of Wings

You may wonder why a man who sold chicken wings is on a website about music in the Twin Cities, but Leland Carriger didn’t just sell wings anywhere – he made the rounds to the bars around town, where the drinking and dancing crowds were eager to see him and hoped he didn’t run out before he got there! This is the story of a real entrepreneur.

EARLY LIFE

The following information comes from a search of the Minneapolis Star Tribune and Ancestry.com

Leland Marques Carriger was born on January 26, 1920, in Sioux City, Iowa. The 1930 Federal Census shows that his mother was a cook for a private family on Aldrich Ave No. headed by a railroad porter.

An intriguing note is that the 1937 city directory listed his occupation as Entertainer.

He served in the Army during World War II, February 9, 1942 to October 1, 1944. While he was gone his wife Lorraine gave birth to their son Leland Eugene on October 26, 1942 in Ramsey County.

In 1957, a letter to the editor signed Leland Carriger (no middle initial) protested racial prejudices, admitting that although he had a below average education, income and home, he was trying to better himself for his children.

In 1961, Leland Carriger was fined $40 for being found in a tippling house.

In March 1962, Leland M and Lorraine E Carriger divorced.

In 1964, Leland M Carrigan was convicted of Aggravated Forgery and was sentenced to five years in workhouse, stayed pending further action.

THE KING OF WINGS

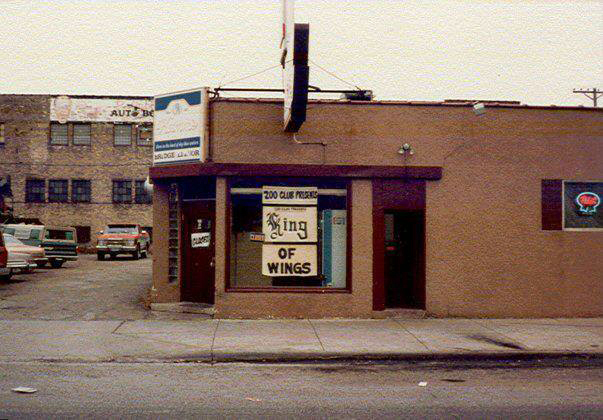

Carrigan became the Wing Man, making the rounds in his white van with his logo on the side.

His headquarters moved to a building by the 200 Club, pictured below.

END OF THE WINGS

In October 1977, Leland M, living in Minneapolis and Detroit, was indicted for tax evasion for 1970. He had reported his income as $1,946 and paid $300 in tax, when the government said he should have reported $43,000 and paid $11,000 in tax. “Carriger was convicted on seven counts involving dealing in heroin and sentenced to 21 years in prison in US District Court in Detroit. (Minneapolis Star, Friday, October 14, 1977, Page 12B)

Rumors swirled that Leland was murdered by some kids on the north side, who collected $83 for their trouble. Surely this would have been reported in the paper, but I found nothing.

Leland M. Carrigan died on January 21, 1993. There was a very short obituary in the paper that gave no clues about the circumstances or where he was living. He was buried at Fort Snelling.

KING OF WINGS RETURNS

On May 30, 2017, the Minneapolis/St. Paul Magazine printed a story by Dara Moskowitz Grumdahl about Robert Patterson, who was bringing back the recipe used by the King of Wings.

Here is the text of the article:

Back in the day, black Minneapolis had its own food truck that drove chicken wings to legendary clubs like the Nacirema and Fox Trap. Now Robert Patterson is trying to bring back the legacy, one wing at a time.

What’s the taste of North Minneapolis? That’s a complicated question. Unlike most African-American urban centers, North Minneapolis doesn’t have an obvious food legacy. There’s no decades-old soul food hub or layer cake specialist linking, say, Prince’s parents to present tables. There is, however, one current in deep food history—and a local man working to turn that link into something strong we can all catch hold of.

The story starts with a man, a legend: Leland Carriger, AKA the King of Wings. He was born in 1920, and he lived in North Minneapolis and worked at Honeywell. In his off hours he worked on his secret chicken wing spice recipe. Once he perfected it, he started driving the wings to bars in a big van. This would have been in the early 1970s. Soon he had a 6-foot-tall mixer just for his spice blend, and went through thousands of pounds of chicken wings a week.

“[Carriger] was the black Colonel Sanders,” remembers Robert Patterson, 53, who went to work for the King in 1978, by which time the business was thriving. Patterson was 14, and his mom knew the King. “One day she said, ‘Bob, do you want to help the King make wings?’ Hell yeah! There was no other answer,” Patterson tells me when we meet at Bunny’s in Northeast. “I knew those wings, everyone did. He’d pull out front, people would see him. ‘Aww the King of Wings is here!’ And there would be a rush to get wings before he ran out. You want those wings before he ran out—definitely.”

On Saturdays, Patterson would show up around noon to the kitchen Carriger had assembled in his tuck-under garage. While listening to tapes of Parliament Funkadelic and Grand Master Flash (played low because Carriger objected to offensive lyrics), Patterson and a handful of other boys would take a torch to the wholesale wings to get any stray feathers off. Then they’d tuck the wing tips under the largest bits to form a neat triangle. They’d fry each one hard, brush it with butter, and hit it hard with the secret spice blend. Three wings got tucked into a foil bag that was stapled shut with a napkin. The bags were stacked 48 to a cooler bucket, and then loaded in the King’s powder-blue van around dinnertime. Once the van was loaded up with 30 or so buckets, the King of Wings would pay the boys and head out into the night.

He’d start in the cultural core of African-American North Minneapolis—at the Elks’ Lodge and the Cozy Bar and Lounge, the latter of which often hosted Prince’s dad’s jazz band. He also hit up the Riverside Supper Club.

After the North hot spots, it was across the river into Northeast, to Tony Jaro’s River Garden, the Polish Palace, the 331 Club, the Vegas Lounge, and the enormous country-western bar that’s now Psycho Suzi’s. He’d hand a bag of wings to the bouncer and wind through the crowds of regulars—a dollar a bag. I ask Patterson about the well-known race tensions between North and Northeast at the time, and he says the King of Wings found his own path through it: “Even if you’re racist, the food is good, and you’re going to eat it.”

Next it was downtown, to the Fox Trap, the dressy center of the world for African-Americans of Soul Train–era Minnesota. The King of Wings would usually draw some customers from the corner arcade, Rifle Sport, too. Next he’d head to Cedar-Riverside, to the Viking Bar, the 400, the Cabooze, and Whiskey Junction. “The bikers, the hippies, they all knew the King of Wings,” says Patterson.

South Minneapolis was the final stop on this side of the river. He’d hit the Spruce Lounge, the Hexagon, Norma Jean’s, Mr. Nibs, an African-American spot called The Temple, and the Nacirema. (I ask if Prince, who would have been hanging out in south Minneapolis in those days, ever tried those famous wings. Patterson expects he must have: “If you’re black from Minnesota in those days, everybody knows everybody,” he says).

Next it was over to St. Paul, to the People’s Choice on Selby, and another Elks’. This world the King of Wings raced through is now gone. The Nacirema, the People’s Choice, the Cozy Bar—the Twin Cities African-American pop culture hot spots have been overwritten by an uncaring world. The Fox Trap, which was also the name of an unreleased Prince song from 1982, is now Sneaky Pete’s, the beer pong hub. “The King is the only thing that is actually legend that we still have,” says Patterson. “That’s why I had to bring it back.”

Patterson left the King of Wings so inspired by Leland Carriger’s work that he went on to spend an entire career cooking in expense-account restaurants like Ruth’s Chris Steak House, Morton’s, Murray’s, and even for Wolfgang Puck at 20.21. Carriger went on to establish a King of Wings freestanding restaurant near the corner of Washington and Broadway, but he died in 1993 and eventually so did his business. Patterson went on to raise five kids, and, after 35 years in professional kitchens, retired. Then he realized what he really wanted to do. He wanted to bring back the taste of the King of Wings. He worked with Carriger’s daughter to decode the recipe the King left behind—it was written with misleading information, to foil recipe thieves. “I made at least 20 test batches,” says Patterson. But he knew the taste—he knew it the way you only can when you’d ride the bus home covered in the spice blend, the taste of your dinner-break wing still on your lips. “Finally—I got it.”

Now he’s bringing this Twin Cities food history back. Patterson’s King’s Royal Seasoning spice blend is being used on chicken wings at the VFW on Lyndale near Lake, at both the Bunny’s Bar and Grill in St. Louis Park and the new one in Northeast, and it’s for sale in a few local stores, including the So Low Grocery Outlet in North, and Sosa Foods on 39th and Minnehaha.

So how can I describe the taste of the wings, which I sample at Bunny’s? The main thing they bring to mind, for me, was the time I had wings at the now-defunct Lucille’s Kitchen on the Northside. They used the King of Wing’s spice. Also, they remind me of the wings at Arnellia’s—the St. Paul jazz club that just closed. They are salty, with a little thyme, a little curry, the barest hint of red pepper. They taste like the Twin Cities—not too spicy, and like nowhere else on earth. Patterson says he runs into old-timers all the time who tell him one thing about his wings: “Those are my wings! That’s them. You brought back my wings!”

If in some strange stroke of luck the King of Wings spice blend takes off and makes him a millionaire, Patterson knows exactly what he’d do. He’d take over the old Sam Goody space on Hennepin off 7th Street, and open a King of Wings restaurant. He’d hand out wings in bags, ones that had a good long time for the butter to mix with the spice blend and get good and dirty. And no sauce, please, that’s not how it’s done. Then everyone could know that taste of North Minneapolis. “I loved it, I want everyone else to love it,” Patterson tells me. “It’s sad to say—but what else is left? What else is there? Hell, we don’t got Prince anymore.” But we do have a little local spice that Prince, and his mom and dad, might recognize.