Loeb Arcade and the Hale Block

The Loeb Arcade Building and the Hale Block were located at the corner of Hennepin Ave. and So. Fifth Street in the heart of Downtown Minneapolis. The Hale Block, on the corner, was nestled inside the Loeb Arcade. Sadly, the area is a parking lot now, but had been a hotbed of entertainment in the heyday of Minneapolis.

MUSIC VENUES IN THE HALE BLOCK

This page is about the history of the Loeb Arcade and the Hale Block only. There were three addresses in the Hale Block that provided entertainment to the people of Minneapolis and beyond. Because the length of this page got confusing and out of control, I’m going to put each address on a separate page. I hope this causes no inconvenience. Those addresses are:

THE LOEB ARCADE

In February 1914, a permit was issued to demolish buildings at 509 Hennepin and 7 – 13 So. Fifth Street. These were brick buildings that had been built between 1898 and 1906.

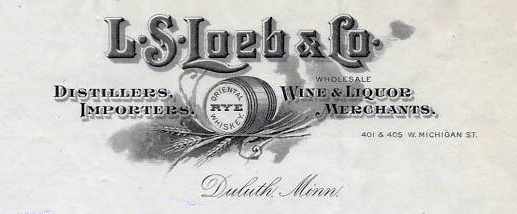

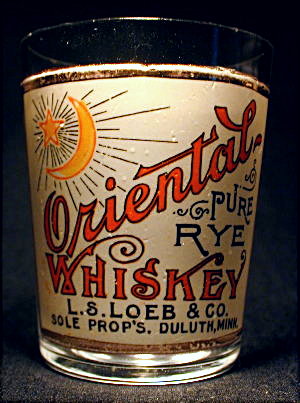

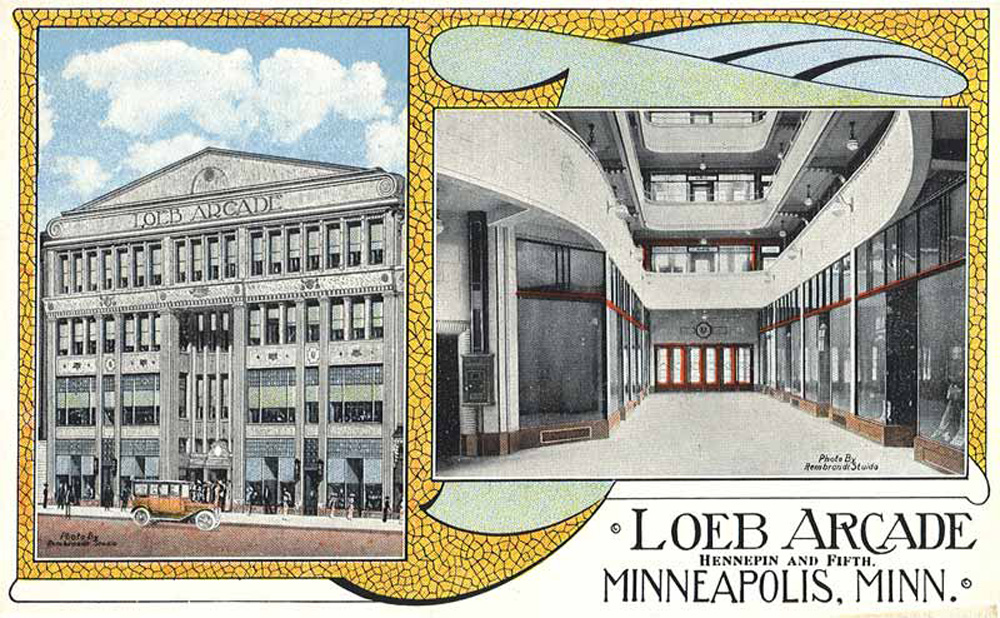

In their place was built the Loeb Arcade, an L-shaped building that literally surrounded the Hale Block. It also had frontage on Hennepin Ave. and So. Fifth Street. The addresses of the Loeb Arcade were 509 – 513 Hennepin Ave. The Loeb Arcade Building was a neo-shopping mall, built by L.S. and S. Loeb of Duluth. L.S. Loeb & Co. was incorporated in 1905 and made some manner of liquor.

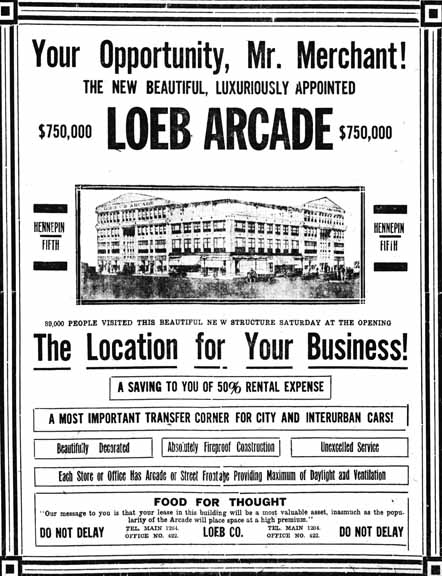

The architect was Ottenheimer, Stern, & Reichert. It was built out of concrete and was five stories high. In late 1913, the Loebs estimated the construction cost to be $300,000. An ad in the Minneapolis Journal (November 8, 1914) indicates that the actual cost came in at $750,000. The building opened on November 7, 1914. In 1922 there was a $40,000 addition to 511 – 513 Hennepin Ave. (88’ x 157’).

Minneapolis Tribune, November 8, 1914

A program described the building:

With reference to the Minneapolis arcade, this structure is pleasing in its modern architectural beauty and represents an investment need bring $750,000. Four stories in height of modern fireproof steel and concrete construction, the exterior is done in a brown Terra-cotta. Spacious entrances on Hennepin Avenue and 5th Street respectively admit into a equally spacious corridor of mosaic flooring presided on either side, according to the arcade idea, by the continuous chain of storerooms appointed in mahogany and white marble basing the corridor some eighteen feet in width leading from street to street affords a convenient meeting place or shelter from the weather and is a shortcut to those passing through.

An upward glance discloses a tastily conceived color scheme of striking white and camel Terra-cotta with rich green and brown Three large balconies completely circling the corridor on either side and bridged at the center of the building permit the comparison of a beautiful amphitheater lighted by a continuous skylight at the top of the structure. A most modern lighting system proves the building is successfully lighted by night as by day.

In his book Lost Twin Cities, Larry Millett explained that the building was patterned after indoor malls built in Europe in the late 18th Century, which had shops “stacked several stories high.” Those malls in Europe catered to the wealthy, but the stores at the Loeb Arcade were aimed at the middle class.

Loeb Arcade lobby, January 1952. Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

One entrance to the Loeb Arcade on Hennepin Ave., 1955. Photo Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Northern States Power had leased about 70 percent of its space, but when it moved to its new headquarters at 414 Nicollet Ave. on about September 1, 1965, the building was left empty, and its building manager stated that it had “no value.”

The Loeb Arcade commenced demolition on March 7, 1967. A large photo of the rubble graced the front page of the Minneapolis Tribune the next day. The first demo permit was taken out on December 30, 1965, but a final lease held up the wrecker for a year. A second permit, with another company, was taken out on November 4, 1966.

Below is a 1967 photo of the remaining Hale Block, where you can see the remains of the Loeb Arcade’s higher floors on the next building.

Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

THE HALE BLOCK

The so-called “Hale Block” stood right on the corner of Fifth and Hennepin. It was completed in March 1880, with seven stores on the first floor, and ten “French flats” on its second and third floors. The idea of putting apartments above stores was innovative at the time, and the Minneapolis Tribune gave it a glowing review when it opened. (March 12, 1880) The architect was the renowned L.S. Buffington, who listed the building in his advertising. It was constructed by E.A. Harmon. The addresses of its storefronts were 501 to 507 Hennepin and 1 to 7 So. Fifth Street The building measured about 60’ x 60’ and was three stories tall.

Like any commercial building, the Hale Block (there were other Hale Blocks, including one in St. Paul) had a variety of different businesses. It also had its share of tragedies. Here are some highlights in its early history:

- In March 1887, a company in Philadelphia made an offer to buy it, tear it down, and build a 10-story office building. Owners E.A. Harmon and his uncle turned it down.

- On September 20, 1887, Phineas Chamberlain, a distraught attorney from Vermont, ended it all by jumping from his third floor window.

- In March 1890 the building was quarantined for measles.

- On August 7, 1890, a storm likened to a cyclone lifted the roof several inches off the building, scaring the bejeepers out of the people inside.

- In November 1896 the building was owned by S.S. Sprague of Rhode Island, as revealed because he died right then.

- On March 19, 1899, a night time fire required firemen to rouse sleeping residents and carry them down ladders to safety. At the time the building was owned by Charles H. Sprague of Rhode Island.

- In September 1901 it was purchased by the Consolidated Land Co., headed by Henry Sprague of Rhode Island.

- In July 1903 the Hale Block was remodeled to add two new stores on the Fifth Street side and expand a storefront on the Hennepin side. Permit cards are unclear whether the dimensions of the building changed.

- On January 25, 1913, L.S. and S. Loeb, who were building the Loeb Arcade around the building, negotiated a 100-year lease from the Consolidated Land Co. The Loebs (again) planned to tear down the building and build a vaudeville theater.

- When the new Loeb Arcade opened on November 7, 1914, once again the Hale was not expected to survive: “Pending the expiration of leases in the building that occupies the corner space, the Arcade will remain as it is. Later it will be added on to by the construction of a building of similar architecture on the corner.” (Minneapolis Tribune, November 8, 1914)

- On June 29, 1921, the Hale Block suffered a devastating fire causing $300,000 in damage and injuring four firemen and the proprietors of two businesses. Fireworks sold in Silverman’s Grocery Store were set off by the flames, making it a spectacular sight, and firemen had a difficult time keeping spectators away. (Minnesota Daily Star, June 30, 1921)

- On December 3, 1926, the Loeb Arcade Building Corp., a group of Minneapolis investors, bought both buildings from the Loebs. The cost was $500,000 for the buildings and $200,000 to buy out their 100-year lease. The new owners, for the third time, planned to tear down the poor Hale Block, and (again) build a 10-story building on the site. The combined footage was 140’ on Hennepin Ave., 157’ on So. Fifth Street, and 192’ in the alley.

- In 1951 the Loeb Arcade, including the Hale Block, was purchased by a syndicate headed by Julius Epstein of Chicago for about $600,000.

FIRE AT THE HALE BLOCK

On October 25, 1954, a spectacular fire swept through the original 1880 Hale Block, totally destroying the three-story building. Ten businesses were destroyed:

- Vic’s Restaurant and Cocktail Lounge, 507 Hennepin

- Foreman & Clark men’s clothing store

- Fanny Farmer Candy shop

- New West Shoe Repair shop

- Sunshine Florists, 503 Hennepin

- Arcade Men’s shop

- Loeb Luncheonette

- Twin City Loan Co.

- McGlynn Bakery

The first alarm came in at 1:36 am. Two more alarms came in within minutes, plus two more alarms for special equipment. A total of 23 fire rigs were on the scene – about three-fifths of Minneapolis’s fire equipment. The rigs and hoses totally blocked off Hennepin Ave.

There was smoke damage to the adjoining Loeb Arcade building, where NSP housed its main office and employed about 250 employees in upper floor accounting offices, but fire walls and doors prevented the fire from spreading.

Four firemen were overcome by smoke and five more were rescued from the roof by ladder before it collapsed into the third floor cafeteria of Northern States Power. The cafeteria eventually ended up in the basement. Other fire fire fighters escaped moments before a marble stairway leading to the Foreman & Clark store on the second floor collapsed.

Big Jay McNeely’s band, which had been knockin’ ’em dead at Vic’s since at least May 1954, suffered an $8,000 loss in instruments and about 30 suits. A.B. Cassius headed a committee that held a benefit dance for McNeely on November 7, 1954, at the Labor Temple “so that they can get back to their homes and maybe a down payment on some new instruments.'” reported the Minneapolis Spokesman. “Hear the Twin Cities’ Finest Musicians.”

The origin of the fire was traced to orchestra’s dressing room in the basement of Vic’s. Although arson inspectors attempted to determine the cause of the fire, the basement was so full of water and debris that an inspection was too dangerous. (Minneapolis Star and Tribune, October 26, 1954)

At the time it was characterized as the year’s worst fire, causing damage estimated at $750,000.

Hale Block fire – photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Hale Block fire – photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Hale Block fire – photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

THE NEW HALE BLOCK (It wasn’t called that anymore but I like the name)

On the day after the fire, city building inspector Donald Erickson ruled that the owners of the building would not be able to reconstruct it, although the outside walls were still standing, because more than 60 percent of the building was destroyed. (Minneapolis Star, October 26, 1954) The old building was demolished (wrecking permit January 25, 1955).

A building permit was approved to build a replacement building on April 25, 1955, in the same spot as the old one. The dimensions of this building were 83’ x 87’, and despite all those plans over the years to replace the Hale Block with a ten-story building, the replacement for the three-story structure was only two stories high. (It would have been three stories if NSP wanted the space.) The architect was Charles Hausler. This building stood on the corner for many years, anchored by Fannie Farmer.

The second Hale Building was demolished in 1986. The corner is now a parking lot.