Guthrie Theater

THE WALKER ART CENTER

Although the concerts listed here were held at the Guthrie Theater, the vast majority of them were booked and sponsored by Walker Art Center. The Walker is a museum that actually started as a collection of items that lumber baron T.B. Walker kept in his mansion at 803 Hennepin Ave., now the site of the State Theater and the Walker office building. In 1926, Walker built a gallery to house his collection on the site of the present Walker Art Center. That building was demolished in 1969 and a new building replaced it in 1971. It was expanded and modernized in 2005. Ironically, instead of holding T.B. Walker’s collection, his museum became known for its collection of modern art.

THE WALKER CENTER ARTS COUNCIL

According to material in the Walker’s institutional records, the Center Arts Council (CAC) was a volunteer organization under the aegis of the Walker Art Center that organized performing arts for the Walker. It was active from 1954 to 1971. Staff coordinators were James Elliott, John Ludwig, and Jay Belolli.

SUMMER JAZZ SERIES

Before the Guthrie was built, the CAC sponsored various events, notably an outdoor jazz concert series featuring local cornetist and bandleader Paul W. (Doc) Evans. The concerts were held in a remodeled open-air court at the rear of the Walker, newly painted and equipped with a stage and canopy, lighting, and greenery. This series, always featuring Evans, began on June 30, 1953, and the first concert drew 700 people, according to Norman Houk of the Minneapolis Tribune, reporting the next day. In 1958, Herb Pilhofer and his modern jazz group took over a significant part of the schedule. In 1959, attendance for opening night was a record 1,250. The series continued through 1961.

In 1962 the Minneapolis Star and Tribune were on strike, but the Minneapolis Daily Herald reported that the Walker sponsored a program called “Jazz ’62-II,” on the south yard of the Walker Art Center.

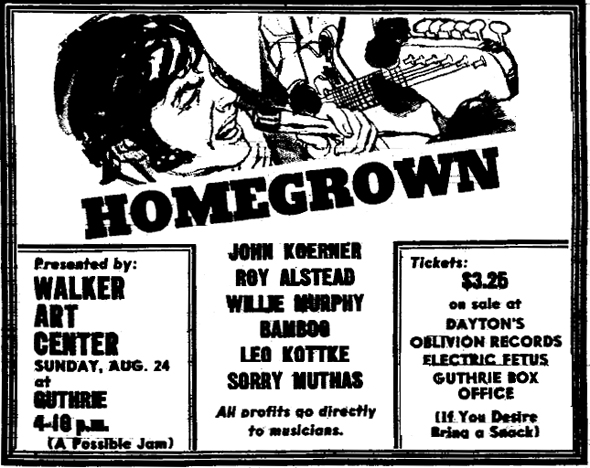

Another interesting CAC event was called “A Happening in a Mushroom Cave,” featuring artist Allan Kaprow in the Wabasha Caves on November 17, 1962. Other notable events sponsored by the CAC were Bottlenecks I (1970) and II (1971), which were frolics in Loring Park with local bands, theater happenings, etc.

Between the Walker’s first concert at the new Guthrie Theater in May 1963 and John Ludwig’s appointment as the Coordinator for the Guthrie and the Walker in the spring of 1964, one would suppose that it was the CAC that technically booked the first year’s shows at the Guthrie.

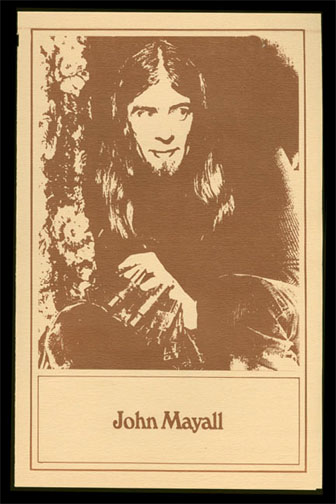

JOHN LUDWIG

According to his biography in the Walker’s archive, John Ludwig (1935 – 1995) was appointed coordinator for the Guthrie Theater and the Walker Art Center in the spring of 1964. He was responsible for scheduling events in the Guthrie Theater when the theater company was not using the space. It was Ludwig, also continuing to rely strongly upon recommendations from the volunteers of the Center Arts Council, who began booking pop and rock performers in the late 1960s, such as Janis Joplin (August 1968), Blood, Sweat and Tears (January 1969), Led Zeppelin (May 1969), and the Who (June 1969). One CAC member, Suzanne Weil, was in particular a driving force behind the bookings of these concerts that also included dance events along with rock, jazz, folk, blues, and world music shows. In January of 1969, Ludwig began to devote most of his efforts to the Center Opera Company, which ended its association with the Walker Art Center that same year.

SUZANNE WEIL

Suzanne Weil was hired as a consultant during this transitional period to formalize her longstanding involvement in shaping the Walker’s concert program through her active role in the CAC. Ludwig left the Walker to become the full-time general manager of the Center Opera Company in July 1969. Weil was appointed full time Coordinator in July 1969 and greatly expanded the Walker’s performing arts program with the opening of the Walker’s Barnes building in 1971.

She was active on the Jazz Committee and became president of the CAC in 1969. In January 1969 she was hired as a consultant to assist the Performing Arts Coordinator Ludwig, as he prepared to leave.

It appears that Weil had a great deal of influence on the acts that were booked before she was officially appointed to the Coordinator’s position in July 1969. In an article by Robert T. Smith in the Minneapolis Tribune dated June 10, 1969, he has already identified her with that title and he wrote that she took the job six months ago. He said that she brought in Pete Seeger (March 22, 1969), Led Zeppelin (May 18, 1969), and Blood, Sweat and Tears (January 16, 1969).

Weil’s biography in the Walker archives reads, in part:

Under Weil’s leadership, the Performing Arts department presented dance, music, poetry, theater events and residencies. The program framework that Weil developed continues to shape the Performing Arts at the Walker Art Center.

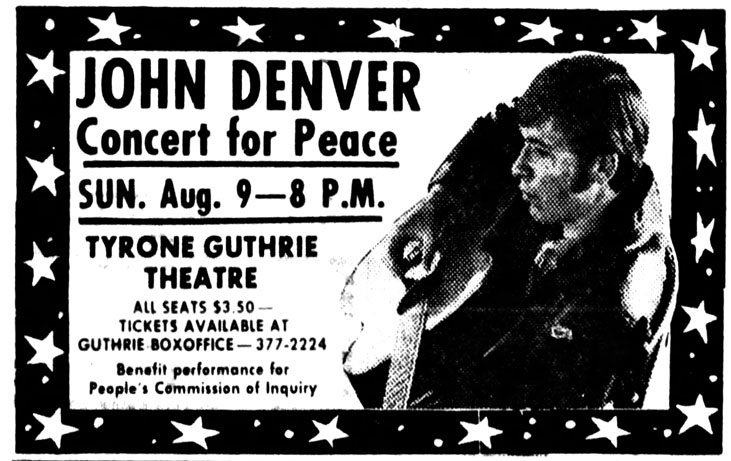

Weil also became known as a rock promoter after she began scheduling rock concerts on Sunday evenings at the Guthrie Theater. Weil booked legendary rock musicians at the start of their careers. Among the artists she brought to the Twin Cities were Elton John, the Grateful Dead, the Mothers of Invention and Patti Smith. The concerts served to fill many gaps. Bands on a tour general traveled Sundays without stopping for a performance. The Guthrie Theater was dark on Sunday nights. Weil connected the dots and booked acts on Sunday nights, thus providing the area with a popular series of Sunday night concerts. The concerts also provided much-needed revenue to present poets, choreographers, and avant-garde musicians; the core of the Walker’s performing arts program.

Weil had a personal and easy style with the artists she presented, as reflected in her correspondence. She made sure she knew what the artists required for their visits, as well as their preferences for things as food, housing, and transportation. Often artists would stay at her house and her hospitality became legendary.

Case in point: in his column in the Tribune dated June 10, 1969, Robert T. Smith reported that when Pete Seeger came to town, she met him at the airport, drove him to his hotel, and then went home and baked him some some bread. “What do you do for Pete Seeger?” she said. “He makes you want to bake bread.”

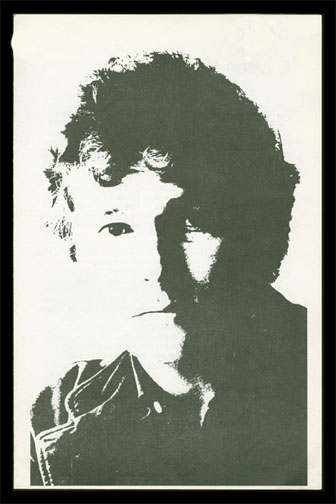

Photo of Suzanne Weil copyright Mike Barich

**It should be pointed out that rock acts had been booked at the Guthrie as early as November 1967 with the Butterfield Blues Band, and would have been earlier if the Blues Project hadn’t cancelled in July 1967. Janis Joplin had appeared in August 1968. Also, the text above might be a little misleading, in that the Grateful Dead and the Mothers of Invention had been to the Twin Cities several times before their Guthrie appearances.

An article called “The New Rock Concert Promoter” in the September 1972 Insider says this about Mrs. Weil:

Her Guthrie concerts are part of the Walker Art Center’s commitment to displaying contemporary art forms. The concerts consistently lose money because she usually brings in acts before they break nationally. Weil picks acts on instinct and on advice of friends, other artists, and anyone else who offers it. Her only criterion is that the artists be developmental or experimental…While Weil has capital to work with, she is only interested in breaking even and exposing the talent.

[The assertion above that none of the concerts made money is not necessarily true. Many Guthrie shows made money that Weil could then use to pay for dance and other events that needed subsidy in the pre-grant era.]

In October 1976, Weil accepted a new position at the National Endowment of the Arts in Washington, CD, as the Director of Dance Programming. Nigel Redden became the Walker Art Center’s Performing Arts Coordinator in November 1976. Weil subsequently served as senior VP of programming at PBS (1982-1989) and executive director of the Sundance Institute.

SUE MCLEAN

With Sue Weil’s departure from the Walker, the Guthrie cemented its interest in controlling the booking of music concerts in-house, eventually hiring Sue McLean as its concert booker, first as a Guthrie staff member, then continuing when she went independent and forming her own agency that had great impact in the Twin Cities music scene. The Walker did continue to occasionally book a few notable concerts at the Guthrie in subsequent years, such as the opening concert of the New Music America Festival in 1980 which featured a triple bill of David Byrne with a string ensemble, Philip Glass and the art ensemble of Chicago, or later concerts with Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time Band.

The Guthrie Theater opened on May 7, 1963. Its first production was Hamlet, directed by the theater’s founder, Sir Tyrone Guthrie. Guthrie and friends Oliver Rea and Peter Zeisler had been disenchanted with Broadway, and wanted to create a theater with a repertory company that would present the classics. The repertory company included George Grizzard, Hume Cronin and Jessica Tandy. The group advertised in the New York Times, soliciting cities that would be interested in sponsoring such a theater. Of the seven cities that responded, the founders were impressed with the demographics but mostly the enthusiasm of the Twin Cities for the project.

The theater was built on donated land behind the Walker Art Center. It was planned by architect Ralph Rapson and completed in 1963. Its 1,441-seat thrust stage was designed by Tanya Moiseiwitsch, with a seven-sided asymetrical platform measuring approximately 32 by 35 feet, raised three steps above floor level.

1966 photo of the Guthrie Theater by Terry Garvey courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Inside the original Guthrie

Michael Bjornberg remembers that

there was a small bar accessed from the seating area that was typically not monitored by security (in those days) – I think it was the “dram bar” perhaps. It would be possible to slip back after shows and mingle with bands.

CONCERTS AT THE GUTHRIE

The Guthrie was not built as a concert venue – it was built to present plays. There were no pillows on the floor, no drinking, no smoking, no dancing, and it was not an interactive experience like the Labor Temple and the Depot had been. Ticket prices were higher, too. But it was a way to fill the seats during the off season, and present visually and acoustically perfect music to 1,437 lucky ticket holders. At first, the Guthrie was used to continue the Walker’s Summer Jazz Series.

Below is a listing of mostly national musical acts that have been presented at the Guthrie, probably 99 percent of which were presented by the Walker Art Center. There are some exceptions here and there, including comedians and local icons such as Koerner, Ray, and Glover. Some performances that were held in the Walker Auditorium are also listed, either because there are photos, or because they include people like Patti Smith or Allan Ginsberg. My sources are listed at the end.

1963

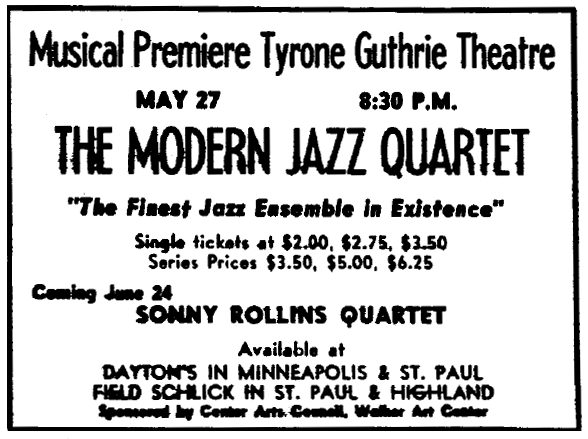

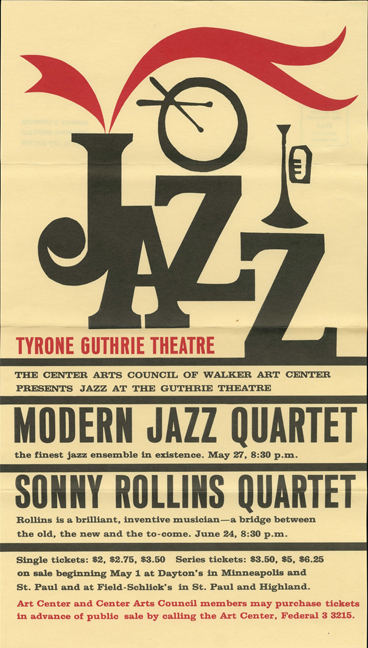

MODERN JAZZ QUARTET

The first musical performance in the new venue was held on May 27, 1963, by the Modern Jazz Quartet. It was billed as part of the Walker Art Center’s 10th Annual Summer Jazz series, given that the original series started in 1953 (see above).

Ad from Minnesota Daily, courtesy Robb Henry

The Modern Jazz Quartet started in 1951 as four members of Dizzy Gillespie’s band, strictly to give Gillespie a break during performances. The members performing in 1963 were leader John Lewis on piano, Milt Jackson on vibraharp, Percy Heath on bass, and Connie Kay on drums. They wore formal cutaway coats on stage, and leader Lewis had two degrees at the Manhattan School of Music.

SONNY ROLLINS

Sonny Rollins and his Trio played to a sold-out crowd on June 24, 1963. The performance was also part of the Walker’s 10th Annual Summer Jazz series.

Dan Sullivan of the Tribune called the music “angry, perverse, often fascinating and ultimately exhausting.” Sullivan didn’t like it, but he said that “you cannot deny that their music is a frighteningly accurate picture of an age unsure of anything but the force of its will to destruction.” Sonny Rollins’ saxophone was “voiced in burps, squeals, shrieks, strangled gasps and just plain clinkers.”

Rollins’ Trio featured Paul Bley on piano, Roy McCurdy on drums, and Henry Grimes on bass.

Poster for the Walker’s Jazz at the Guthrie series, 1963. Source unknown

PRESERVATION HALL JAZZ BAND

Kid Thomas and His Algiers Stompers came to the Guthrie to play – not Dixieland, but New Orleans jazz on July 22, 1963.

It was a large band, featuring George Lewis – the Tribune’s Allan Holbert described him as one of the greatest clarinetists of this century. The band was playing at several places around town during the week. Apparently this was not part of the Jazz at the Guthrie concerts.

1964

The Walker’s Center Arts Council sponsored a series of American Folk concerts in early 1964:

Mountain String Band and Banjo Songs, January 25, 1964: About 1,100 people, “very few in dungarees,” came to hear American mountain music.

- New Lost City Ramblers of NYC: Mike Seeger, John Cohen, and Tracy Schwartz. Dan Sullivan of the Tribune called them “smart enough to have smoothed mountain music into a profitable commodity and wise enough not to have perverted it. They are synthetic but not pseudo.”

- Roscoe Holcomb of Daisy, Kentucky: Dan Sullivan deemed them to be the “genuine article – two modest, simple men who remember all the old songs nobody ever bothered to write down.”

- Dock Boggs of Norton, Virginia

Sullivan congratulated John Pankake, co-editor of the Little Sandy Review for insisting on the real thing for this concert.

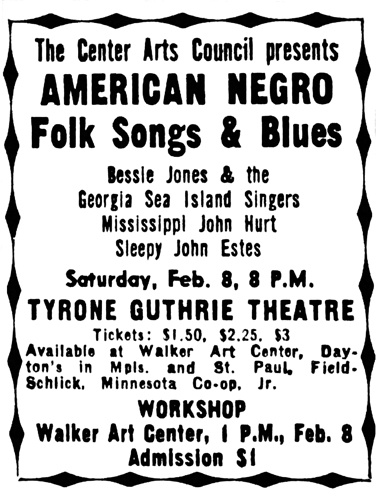

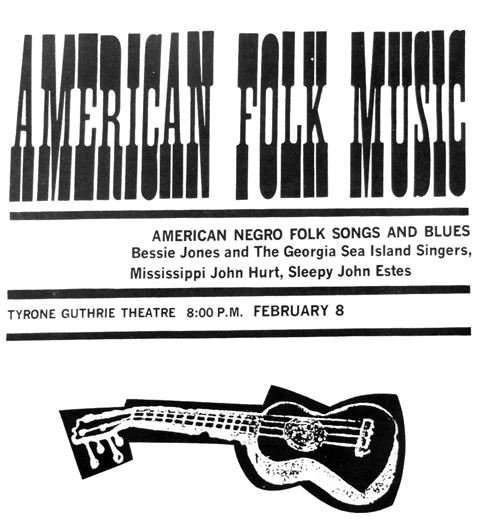

American Negro Folk Songs and Blues, February 8, 1964:

Bessie Jones and the Sea Island Singers of St. Simon’s Island, Georgia. Program notes consisted of a lesson in the Georgia Sea Islands, and a short biography of Bessie Jones, written by Alan Lomax himself.

Mississippi John Hurt, Avalon Mississippi. Program notes provided a biography of Hurt, written by Dick Spottswood of Arlington, Virginia. Will Jones reported that Hurt, 72, was rediscovered about a year prior by record collector Tom Hoskins from Washington, DC. Most collectors of his 1928 records had assumed he was dead. Hoskins found Hurt at home in Mississippi and told him he was going to take him to Washington to record. Hurt was convinced that the record buff was really from the FBI: “I knew I hadn’t done anything sinful, but I went along anyway. Now I’m sorry the FBI man didn’t discover me a few years earlier.” (Minneapolis Tribune, January 24, 1964)

Sleepy John Estes, Lowry County, Tennessee with Hammie Nixon and Yank Rachel. Bob Koester’s program notes indicated that Estes had gone missing for many decades, and most afficionados of his music assumed that he was much older than he was. But when he was rediscovered in 1950, he was only 60 years old, and his career was restarted.

This concert (above) included a folk music workshop at 1 pm.

Minneapolis Star, February 1964

Program image courtesy Grant Johnson

Traditional Ballads and Folk Songs, February 22, 1964:

- Jean Ritchie of Viper, Kentucky

- Doc Watson of Deep Gap, North Carolina with Fred Price and Clint Howard of Mountain City, Tennessee

THEODORE BIKEL

Folk singer Theodore Bikel made his first Twin Cities appearance on February 23, 1964, at the Guthrie, presented by the Minneapolis Chapter of the Hadassah.

Minneapolis Tribune, February 1964

JOHN CAGE

The Merce Cunningham Dance Company appeared on February 25, 1964, accompanied by the music of John Cage and David Tudor – a Walker Center Arts Council concert.

Dan Sullivan of the Tribune called Cage and Tudor’s music a “medley of squeaks, squeals, yowls, yammers, explosions, and general clatter.”

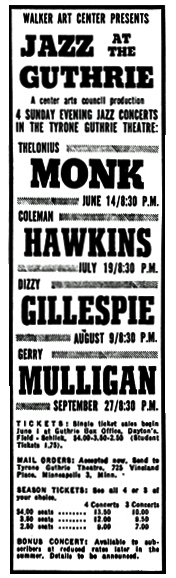

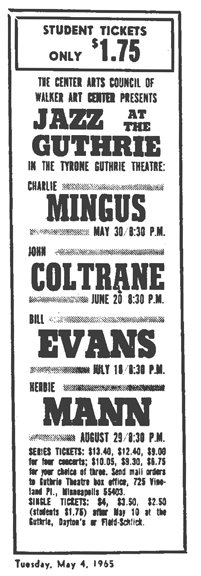

JAZZ AT THE GUTHRIE ’64

The Walker Art Center presented a series of four Sunday evening jazz concerts at the Guthrie starring four of the greatest jazz performers of the era. The series was called the Walker Center Arts Council summer Jazz series. Incredibly, tickets for these concerts were $2.50, $3.50, $4.00, and $1.75 for students.

Minneapolis Tribune, June 1964

The Thelonious Monk Quartet appeared on June 14, 1964. An article (presumably from the Minnesota Daily) said:

Monk’s compositions and innovations in rhythm and harmony have provided major inspiration to modern jazz musicians. He has played a major role in the birth of be-bop and the avant-garde movement in modern jazz.

Dan Sullivan of the Tribune complained about the short concert of only 75 minutes. Monk played piano and his sidemen were Ben Riley on drums, Gene Taylor on bass, and Charles Rouse on tenor sax.

The Coleman Hawkins Quartet appeared on July 19, 1964. With him were Eddie Locke on drums, Paul Neves on Piano, and Major (Mule) Holly on bass. Hawkins played played tenor saxophone.

The Dizzy Gillespie Quintet appeared on August 19, 1964, before a capacity crowd. He and his band played for 2 1/2 hours. In his Quintet were James Moody, on Flute, tenor and alto saxes; Christopher White on bass; Kenny Baron Piano, and Rudy Collins on drums.

The Gerry Mulligan Quartet, with Dave Bailey, Bob Brookmeyer, and Bill Crow, appeared on September 27, 1964.

The Preservation Hall Jazz Band with Sweet Emma Barrett and Her Boys performed on October 18, 1964. Sweet Emma was the “belle gal,” dressed in a flaming red suit and beany to match. Around her right calf was her trademark band of bells. She danced and (this is unclear) played banjo while seated in a straight backed chair. Sidemen included Percy Humprey, Emanuel Sayles, Alcide Pavageau, Jim Robinson, Josiah Frazier, and Willie Humphrey, Jr. This was a bonus Jazz concert for summer Jazz at the Guthrie subscribers. The album “Sweet Emma and Her Preservation Hall Jazz Band” was recorded at this session. Presented by the Walker in association with Jass Inc.

1965

GEULA GILL

Geula Gill & Company brought her show to the Guthrie on February 27, 1965, presented by the Minneapolis Chapter of Hadassah. Ms. Gill was an Israeli singer and actress, and had appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1948. She could sing in a few languages and several octaves. She was accompanied by a bass player and two guitar players, who sometimes sang with her.

Allan Holbert of the Tribune said that she and her group were so appreciative to Peter, Paul, and Mary for the song “If I Had a Hammer” that they thought about changing their name to “Abraham, Isaac and Sarah.”

Minneapolis Tribune

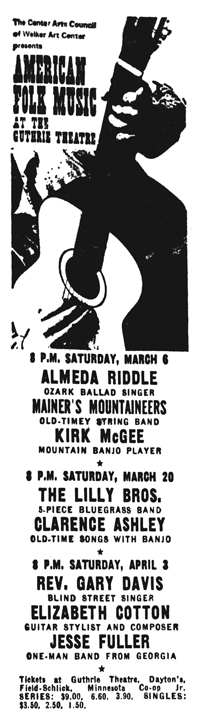

AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC SERIES

The Walker Center Arts Council presented three Saturdays of Folk music in the Spring of 1965.

Folksingers Almeda Riddle, Mainer’s Mountaineers, and Kirk McGee appeared on March 6, 1965.

Folksingers the Lilly Brothers and Clarence Ashley appeared on March 20, 1965.

Minneapolis Tribune, February 1965

Reverend Gary Davis, Elizabeth Cotten, and Jesse Fuller performed on April 3, 1965.

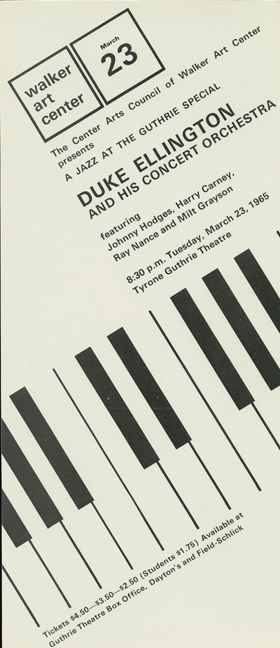

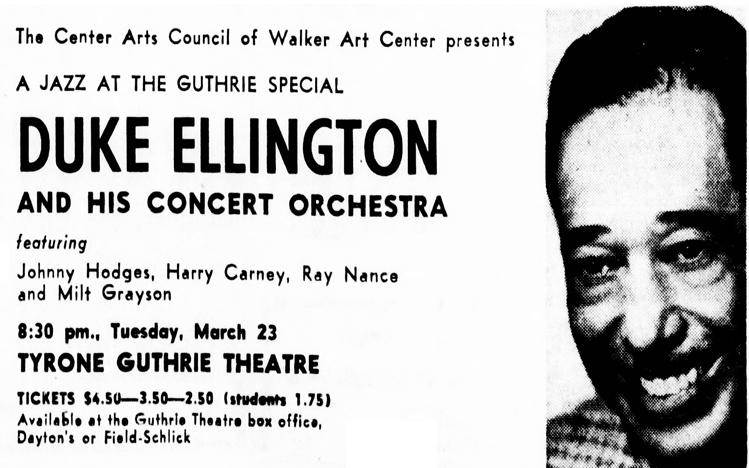

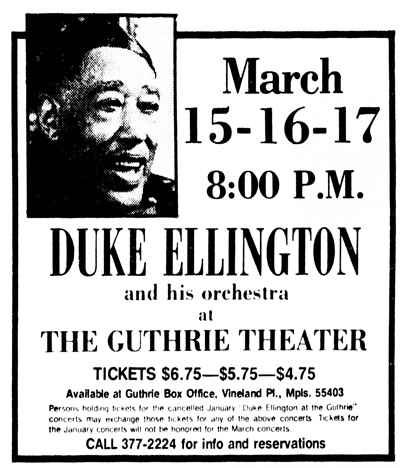

DUKE ELLINGTON

Duke Ellington and His Orchestra, , performed on March 23, 1965, to a sellout crowd, presented by the Walker Center Arts Council.

Minneapolis Tribune, March 1965

Don Morrison, Star columnist, reflected that he had seen a Duke Ellington show 19 years ago and it was still the same, and still excellent. Some of the old stars in the band were still alive; Cat Anderson, Paul Gonsalves, Sam Woodyard, Harry Carney, Lawrence Brown, Johnny Hodges, Cootie Williams, Ray Nance, Milt Grayson, and Mercer Ellington.

JAZZ AT THE GUTHRIE ’65

The Walker Art Center again presented a series of four jazz concerts at the Guthrie starring four of the greatest jazz performers of the era. The series was called the Walker Center Arts Council summer Jazz series.

CHARLES MINGUS

The Charles Mingus Quintet, performed on May 30, 1965. The audience was not sold out, numbering about 1,200.

Ad from Minnesota Daily, courtesy Robb Henry

Allan Holbert of the Tribune found the concert for the most part “stimulating, fresh and skillfully presented.” Sidemen were Dannie Richmond on drums, Charles McPherson on alto sax, Lonnie Hillyer on trumpet, and Jaki Byard on piano. Mingus played bass.

Charles Helm:

I stumbled upon info that this Mingus concert, sponsored by the Walker at the Guthrie, was recorded and issued on albums twice. The Guthrie concert was first issued on the Mingus album “My Favorite Quintet” (Fantasy label, 1965) https://www.discogs.com/release/2072924-Charles-Mingus-My-Favorite-Quintet

Then in 1980 it was reissued as one album of the double album set “Portrait” by Charles Mingus on the Prestige label (the other album in this package was a 1964 live show from Town Hall in NYC).

https://www.discogs.com/release/2429223-Charles-Mingus-With-Eric-Dolphy-And-Jaki-Byard-Portrait

For the release of the 1980 Portrait double album the great jazz pianist Jaki Byard, who played with Mingus for both concerts, wrote liner notes. Below is an excerpt of Jaki’s liner notes for Portrait where he describes the generous treatment and reception for the Guthrie show and his encounter with a local woman who was a CAC member (Mingus was infamous for being cantankerous and rude) plus some details on “My Favorite Quintet” and “Portrait.” Cool that this concert was recorded and issued twice on albums and it included this insider info on WAC’s Center Arts Council in action hosting concerts. Mingus’ band at this concert is well deserving of the album’s title My Favorite Quintet.

EXCERPTS FROM JAKI BYARD’S LINER NOTES on the 1965 gig at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis

“……Before the concert, red carpet treatment was in full bloom: limousine service from the airport, cocktails and hors d’oeuves, seminar, then dinner. I noticed this charming older women, all agog over Mingus, just a-chatting away. Finally, she came over to me and right away I asked her: “What the hell is it that you find so intriguing about Mr. Mingus?” She said, “I adore his impudence, he has such enthralling surliness, like an English lord, ya know!” I said, “Uh-huh” (and half understood what she meant). But her statement really helped to turn me on to the behavior of the late Charles Mingus, and I think after that I was more tolerant than ever before of his weird ways.”

“My entire association with Charles Mingus was an honor and a treat — including all the moods, temperaments, personality clashes, cooperation, and feelings of accomplishment and self-gratification. I can’t find any superlatives strong enough to define what those years meant to me. I left Mingus in 1968 primarily because of domestic obligations, and also because I felt an urge to pursue in my own ways some obligatory missionary work in the growing jazz community. But I continued to appear with him, off and on, until 1976.

Jazz, in my language, is a four letter word spelled L-O-V-E. Charles Mingus was one of the people who taught me to spell.”

— Jaki Byard

JOHN COLTRANE

The John Coltrane Quartet performed on June 20, 1965. It was a capacity audience.

Allan Holbert of the Tribune reported that two of his usual sidemen, pianist McCoy Tyner, and bass player James Garrison, had missed a plane somewhere, so local musicians Dub Frazier took over on piano and Maurice Turner filled in on bass. Elvin Jones was there as his regular drummer, and Coltrane played the sax. After the first tune after intermission, Garrison and Tyner finally arrived, and Holbert called it a “striking improvement in the caliber of the ensemble work.”

HERBIE MANN

Herbie Mann performed on August 29, 1965 with his octet.

Mann was described as “the bossa nova pioneer,” and an article said that he had created a new “ethnic jazz” by combining African and Latin American rhythms with American jazz. His sidemen were:

- Dave Pike, vibraharp

- Jack Hitchcock, trombone

- Mark Weinstein, trombone

- Jane Getz, piano

- Earl May, bass

- Bruno Carr, drums

- Carols Valdes, conga drums

BILL EVANS

The Bill Evans Trio performed on September 19, 1965, as part of the Walker Center Arts Council’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series. The audience numbered about 1,100.

Evans was originally scheduled to perform on July 18, but illness forced a postponement to a later date. Evans’ sidemen were Chuck Israels on bass and Arnie Wise on drums. Evans played piano.

Allan Holbert from the Tribune wrote that a lot of local bass players were at the show to see Israels, calling him “tasteful and articulate.”

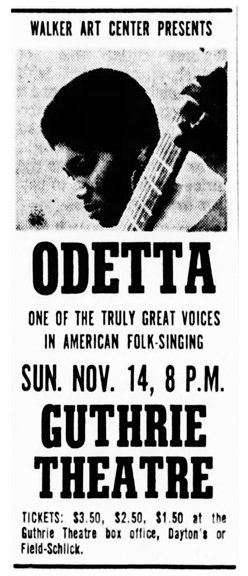

ODETTA

Odetta performed at the Guthrie on November 14, 1965, presented by the Walker. This was Odetta’s first appearance in Minneapolis. The concert was sold out.

Minneapolis Tribune

Critic James Fuller of the St. Louis Park Dispatch gave this review on November 18, 1965:

Odetta… is the only woman folk singer around who could get away with doing the kind and variety of songs she does. Her contralto is recognized as one of the great contemporary voices in folk singing.

The opened the program with some cliches of the folk song business – tunes like “If I Had a Hammer” – and with her warm, honest approach made them sound new. By the middle of the the second half of the program, the crowd was clapping with her on the chain gang songs, and on her third encore, the one “freedom” song she sang all night, the audience joined in the singing and clapping without an invitation.

As reported above, Allan Holbert of the Tribune reported that she started with some overworked folk songs, followed by some more obscure material. She stayed away from the contemporary protest songs, although she did announce that the next number dealt with a racially mixed marriage. Then she launched into “Froggy Went a-Courtin'” She was backed by Leslie Brinage on bass and Bruce Langhorn on tenor guitar.

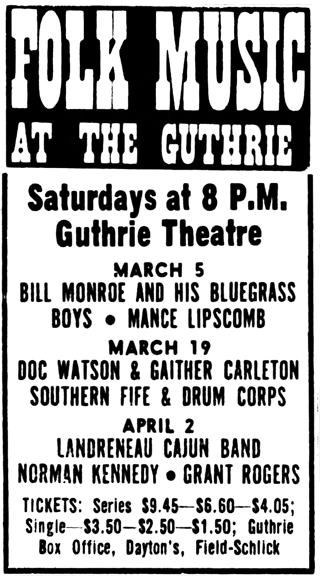

1966

The Walker Art Center ran two concurrent series of musical shows in 1966 – one was the “Jazz at the Guthrie” series, and the other was the “Folk Music at the Guthrie” series. Both genres were quite popular at the time, and the Walker brought in the best of the jazzmen and the most authentic folk music purveyors.

The Modern Jazz Quartet performed on January 21, 1966, as a special Walker Center Arts Council’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” concert.

BILL MONROE AND MANCE LIPSCOMB

Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, with Mance Lipscomb, performed on March 5, 1966, as a part of a Folk Music at the Guthrie series.

Monroe was accompanied by guitar, banjo, bass, fiddle, and Monroe’s mandolin. Maury Bernstein acted as m.c. and told the crowd that the performs would conduct a folk music workshop on March 6, 1966, at the Walker.

Allan Holbert at the Tribune reported that while Lipscomb was a bit hard to understand, he was indeed the real thing.

Tom Scanlan at the Star mused at how many genres Lipscomb sang, and the influence of American “rural Negro music” on music today.

Minneapolis Star, March 1966

The American Jazz Ensemble performed on March 18, 1966, as a Walker Center Arts Council’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” late-night special.

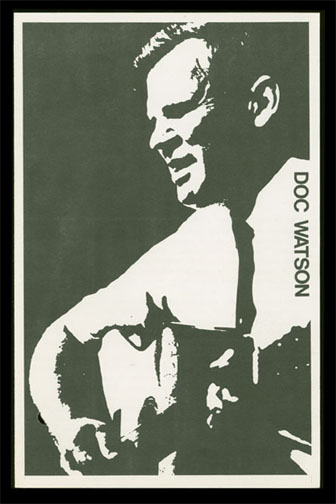

DOC WATSON

Doc Watson, Gaither Carleton, and the Southern Fife and Drum Corps performed on March 19, 1966, as a part of a Folk Music at the Guthrie series. Watson also appeared with his son Merle. He played the guitar, banjo, harmonica, and 12-string guitar.

Tom Scanlan of the Star wrote:

On the same day (March 19, 1966) of Doc Watson’s concert, was a performance of the Southern Fife and Drum Corps. This group was made up of Ed Young, Lonnie Young, and G.D. Young from Como, Mississippi. Despite their name, they didn’t play military music, but “a strange, African-sounding blend of complex rhythms and haunting melody.”

But the high shrill, can fife of Ed Young floating over the driving polyrhythms of the bass and snare drums created a memorable experience. The visual content was almost equal to the musical, with half handing of the player an inseparable part of the artistry. Their music, a remnant of slave culture popular as late as the last decade in rural Southern areas, was difficult and wearing, but for all that, hypnotically powerful.

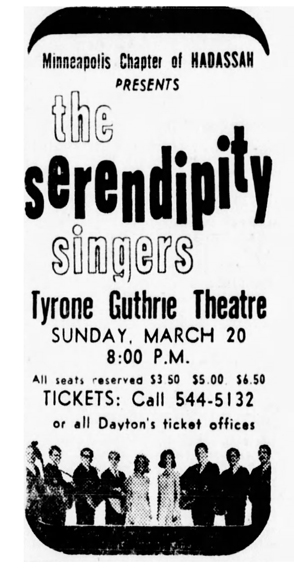

SERENDIPITY SINGERS

The Serendipity Singers appeared on March 20, 1966, presented by the Minneapolis Chapter of Hadassah.

Minneapolis Tribune

The Landreneau Cajun Band, Norman Kennedy, and Grant Rogers performed on April 2, 1966, as a part of a Folk Music at the Guthrie series.

- Grant Rogers, from Walton, New York, sang and played in a “Northeastern” American genre

- Norman Kennedy was from Aberdeen, Scotland and sang Scotch and Gaelic songs of his country

- Adam and Cyrien Landreneau were from Mamou, Louisiana, and they sang in French.

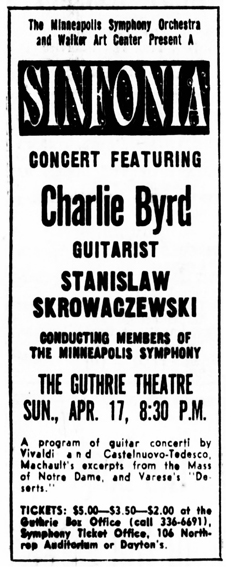

CHARLIE BYRD

Jazz guitarist Charlie Byrd performed two concertos with the Minneapolis Symphony on April 17, 1966, presented by the Minneapolis Symphony and the Walker.

Minneapolis Tribune

Allan Holbert of the Tribune found his performance to be a disappointment. Holbert is rough, calling the first of the two concertos “an artistic failure,” saying “he forgot notes, he missed notes, he produced a tone that is beneath his capabilities.” The second concerto was better, wrote Holbert.

ELLA FITZGERALD

Ella Fitzgerald performed two shows on April 21 and 22, 1966, part of the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series. Both shows were sold out. This may have been the first time that two shows were scheduled at the Guthrie.

The normally reticent Minnesota audience clapped appreciably before and after each song. She came with a trio headed by pianist Jimmy Jones.

Clark Terry and the Bob Brookmeyer Quartet performed on May 22, 1966, part of the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

CHARLES LLOYD QUARTET

The Charles Lloyd Quartet performed on May 22, 1966, part of the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

Lloyd’s sidemen included Keith Jarrett on piano, Cecil McBee on bass, and Jack Jonette on drums. Lloyd played tenor sax and flute.

Where magazine’s promo said that “Lloyd, along with John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, is considered one of the foremost men of contemporary jazz. He infuses the tenor saxophone and flute with a new sound that promises to be the epitome of the New Wave in jazz.” (April 6, 1968)

The headline of Peter Altman’s review in the Star was “Charles Lloyd Quartet Concert is Quite Bizarre.” Peter goes on to call it “incredible, frenzied” and said that at least “at least 100 persons huffed out in indignant and conspicuous protest.” He talks about weird harmonies and unpredictable sifts of tempo. He writes that “the quartet is not an ensemble, it is a conflict. Its members have imagination, strength, and force. If you can stand it.”

Similarly, Allan Holbert at the Tribune called the performance a “puzzlement.” Sometimes the jazz was cool, spontaneous and exciting. At other times it was loud and monotonous, almost if the players were putting us on.”

OSCAR PETERSON

The Oscar Peterson Trio performed on July 24, 1966, part of the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

The Trio had been hit recently by retirements, so the personnel had been changed Bassist Sam Jones had replaced Ray Brown. Drummer Louis Hayes had replaced Ed Thigpen

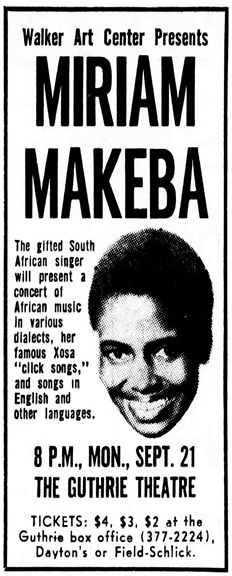

MIRIAM MAKEBA

South African singer Miriam Makeba performed to a near-capacity crowd on September 12, 1966, presented by the Walker.

Minneapolis Tribune, August 1966

Reviewer Thomas Scanlan of the Star wrote that Makeba “dazzled everyone within hearing. Singing a repertoire that alternated among her own African music, Brazilian jazz and a variety of songs in English, Miss Makeba seemed to please an enthusiastic audience with everything she tried.” She could sing in three or four languages, and she received a standing ovation.

Jim Fuller of the St. Louis Park Dispatch noted that she was backed by a trio whose names were not in the program, and she had trouble with feedback from the sound system.

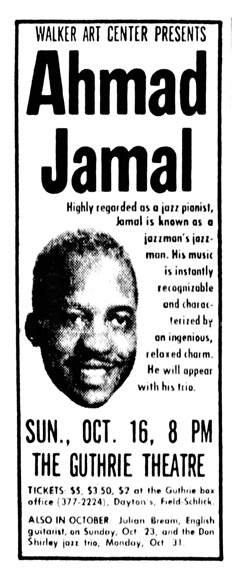

AHMAD JAMAL

Ahmad Jamal performed on October 16, 1966, presented by the Walker. It was a capacity audience.

Minneapolis Star

Although the audience was very appreciative of Jamal’s work on the piano, Peter Altman’s review in the Star is headlined “Ahmad Jamal Trio is Short on Soul.” Jamal’s sidemen were Jamil S. Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on Percussion.

DON SHIRLEY TRIO

The Don Shirley Trio performed on October 31, 1966, presented by the Walker.

Lew Reeve in the Star reported that Shirley had an interest in playing the diverse musical forms of Americana. During the show the trio played a show tune, Protestant hymn, Negro spiritual, military march, and a Scarlatti Sonata. Members of the trio were cellist Juri Taht and Kenneth Fricker. Mr. Shirley played the piano.

1967

ORNETTE COLEMAN

The Ornette Coleman Trio, performed on April 30, 1967, part of the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series. The event attracted half a house.

The rest of the trio was David Izenzon on bass and Charlie Moffett on drums. Coleman played the also sax, the musettte, the violin and the trumpet.

Reviewer Allan Holbert of the Tribune wrote that some of the pieces were avant garde, and some were more accessible, traditional, which got more applause

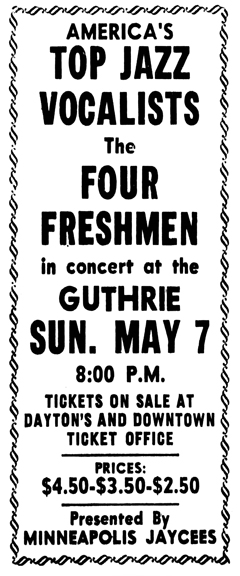

FOUR FRESHMEN

The Four Freshmen, billed as Jazz Vocalists, appeared on May 7, 1967.

The Four Freshmen were Ross Barbour, Ken Albers, Bill Comstock, and Bob Flanigan. The Show was sponsored by the Minneapolis Jaycees’ Arts and Culture Committee.

Minneapolis Star, May 1967

CANNONBALL ADDERLY

The Cannonball Adderley Quintet, with Nat Adderley, performed on May 21, 1967, part of the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

THEODORE BIKEL

Theodore Bikel appeared on June 11, 1967, sponsored by Friends of Torah Academy.

Minneapolis Tribune, June 1967

NINA SIMONE

Nina Simone performed on June 18, 1967, part of the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

Allan Holbert’s review in the Tribune spent half its space focusing on Ms. Simone’s outfit:

She was dressed in a sleeveless, formal pants-suit made of what looked like white basketball net. It was lined, incidentally, with a silky fabric which, in color, could not be distinguished from her skin. Add to this gold-colored, high-heeled slippers, while, tassled armbands and earrings jangling and swinging three inches from her ears and you have my nomination for wildest-looking soloist in the next Downbeat poll.

The photo below is screen grab from a TV performance on YouTube, and it might be the same outfit:

As for her performance, Nina was backed up by her own trio of guitar, bass, and drums players. Holbert wrote,

Hers is an unusually straight-toned voice that penetrates like a not needle. It weeps on the sad songs and crackles with fury on the mad songs. … She does about everything – pop, protest, blues, gospel, folk.

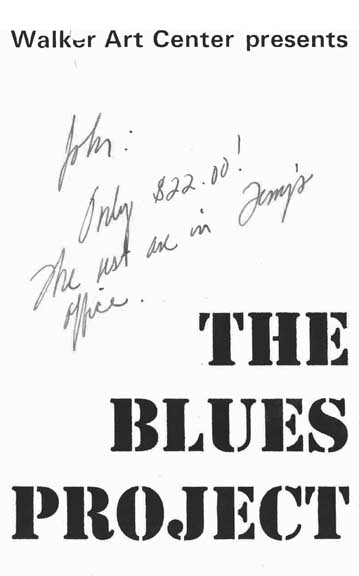

BLUES PROJECT – CANCELLED

The Walker scheduled a concert by The Blues Project at the Guthrie on July 9, 1967. The show was cancelled 48 hours before it was to go on, ostensibly because of the illness of lead singer Danny Kalb. This was just after Monterey Pop, and the band was losing its members, according to Wikipedia.

Minneapolis Tribune, July 1967

Because of the short notice, tickets had been sold and programs printed. The program below was found in the file at the Walker Archives.

Image of Program courtesy Walker Art Center Archives, Performing Arts, Coordinator John Ludwig, Box 5 F8

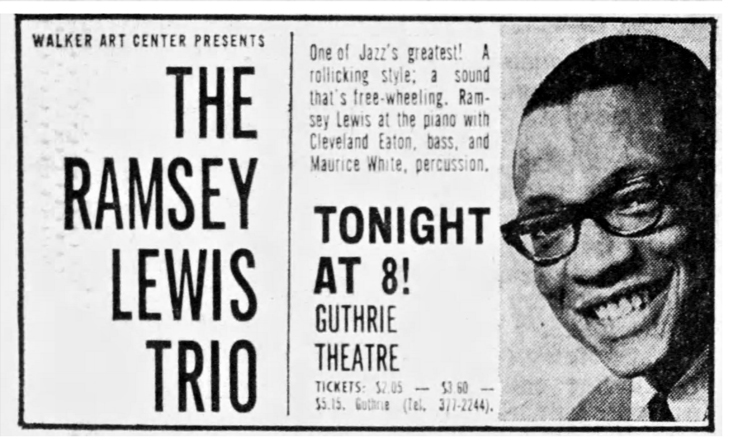

Image of Program courtesy Walker Art Center Archives, Performing Arts, Coordinator John Ludwig, Box 5 F8

The file reveals that the opening act was to be a local folksinger named Kay Huntington, who was to play for 15 minutes, and the the Blues Project was to play for 37 minutes. The show was described as being divided into two halves – the two acts would trade off, but it doesn’t sound like it was intended to be two shows.

John Ludwig, the program director at the Walker who had negotiated the contract, was hopping mad at what he called the “arbitrary” cancellation, and in a letter to the group’s agent at William Morris in New York, seemed to be calling for proof of Kalb’s illness. The Walker was out $450 in printing costs, and he threatened to pass those costs on to the group. Apparently that was a lot of money to lose in the Walker’s tight budget, and Ludwig was rethinking his decision to book rock groups again.

If this had gone on, this could have been the first rock act (“New York Folk Rock”) at the Guthrie.

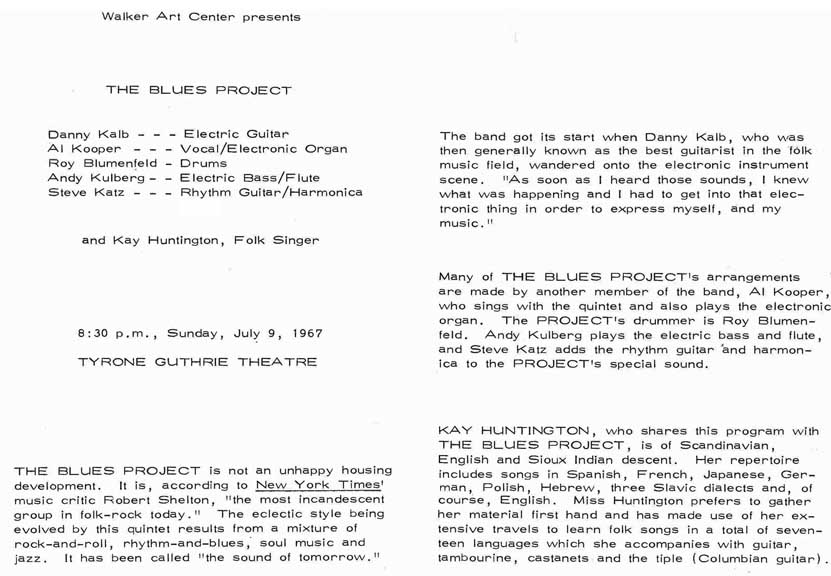

HORACE SILVER

The Horace Silver Quintet performed on July 30, 1967, part of the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

Minneapolis Star, July 1967

Allan Holbert of the Tribune deemed Silver’s music to be pleasant and highly listenable – a little old fashioned, but with a desire to connect the the audience, which a lot of the newer jazz groups didn’t have. Silver’s men were Woody Shaw on trumpet; Tyrone Washington on tenor sax; Larry Ridley on bass, and Roger Humphries on drums. Silver played the piano.

BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE

Buffy Sainte-Marie performed on September 10, 1967, presented by the Walker.

Tom Scanlan of the Star reported that the in-depth series of traditional jazz and folk music concerts have been replace by “a wide-ranging slate of offerings.” Perhaps as a transition, Buffy St. Marie was booked as a folk singer, although she eschewed the name. Scanlan tried to describe Buffy’s “Unique, Exciting” songs, and his final line in the review was “It is engaging madness.”

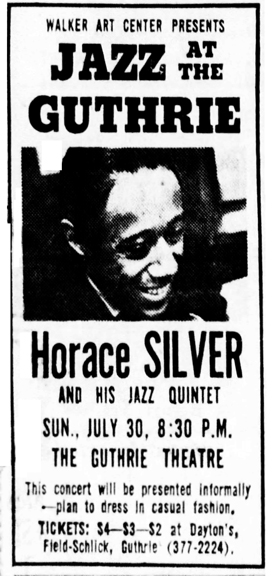

RAMSEY LEWIS TRIO

The Ramsey Lewis Trio performed on September 24, 1967, presented by the Walker. It was a near-sellout.

Minneapolis Tribune, September 1967

Allan Holbert at the Tribune crabbed that even though people enjoyed the show, there was nothing new or experimental about it, therefore, it wasn’t stimulating. He wanted the Walker to bring in “the new, the adventurous, the unproven jazz, the jazz that could practically be exhibited an place else in town.” Lewis’s sidemen were Cleveland Eaton on bass, and Maurice White on drums. Lewis played keyboards.

BABATUNDE OLATUNJI

Babatunde Olatunji, a troupe performing African music and dance, came to the Guthrie on November 5, 1967, presented by the Walker. This performance was in connection with the gallery’s show of Art in the Congo.

Peter Altman of the Star called it “the most relentless, enervating, overpowering total experience to be seen here in months.”

The troupe consisted of five dancers, three drummers; Olatunji was one of the drummers. He was “spreading the gospel” by taking the show around the world. He also hoped to give U.S. Negroes a sense of pride in being black by aletring them to their native cultural traditions.

PAUL BUTTERFIELD

The Butterfield Blues Band performed on November 12, 1967, presented by the Walker.

There were recent personnel changes: Elvin Bishop on guitar, Paul Butterfield on vocals and harmonica, Mark Naftalin on piano, organ, and guitar; Bugsy Maug on bass, Phillip Wilson on drums, and a three-man brass section.

A review by Jim Berman in the Minnesota Daily says that the first show was a disaster, but got better in the second. They were moving away from being a blues band and going into electric jazz. Berman especially applauded Naftalin’s keyboard skills.

Peter Altman’s review in the Star was mixed – the headline read “Almost all Electronics & No Content,” while the last line said that the concert “moved and grooved.” Again, good marks for Naftalin, who Altman called the melodic center. Butterfield’s harmonica provided the most distinctive sound, a “real Negro blues feeling.” But he felt that the group was uncohesive, and that the music was almost all electronic technique and almost no content.

Altman’s review gave no indication that there were two shows.

ROCK COMES TO THE GUTHRIE

The way I see it, the Butterfield show was the first rock act to be staged at the Guthrie. The group was not jazz, not folk, but an electric blues band that had performed at Dayton’s in May 1967, and would appear at the Depot in 1970.

Curiously, it would take a few more rock acts – notably Janis Joplin in August 1968 – for the press to pick up on the change. It wasn’t until June 1, 1969, that the Tribune had this to say:

Walker Art Center, formerly famous for its Jazz at the Guthrie concerts, is now getting into more of a Rock at the Guthrie thing.

IAN AND SYLVIA

Ian and Sylvia performed on December 1, 1967, presented by the Walker.

Ian Tyson and Sylvia Fricker were Canadian folk singers who were making their first visit to Minneapolis in six years – they used to sing at the Padded Cell. Sylvia had written “You Were on my Mind,” and Tyson had written “Four Strong Winds.”

RICHARD DYER-BENNETT

Richard Dyer-Bennett, folksinger, performed on December 9, 1967, presented by the Walker. An audience of 700 came to see him.

According to a review by Phillip Gainsley in the Star, Dyer-Bennet divided his program into four parts: three of which are geographical and one being poems of Shakespeare set to his own music. He accompanied himself on the guitar and lute. He was called back for several encores, in which he demonstrated his mastery of dialects and inflection.

1968

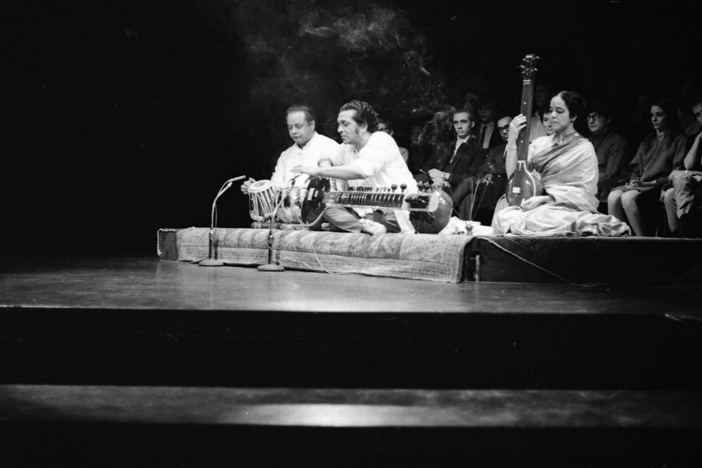

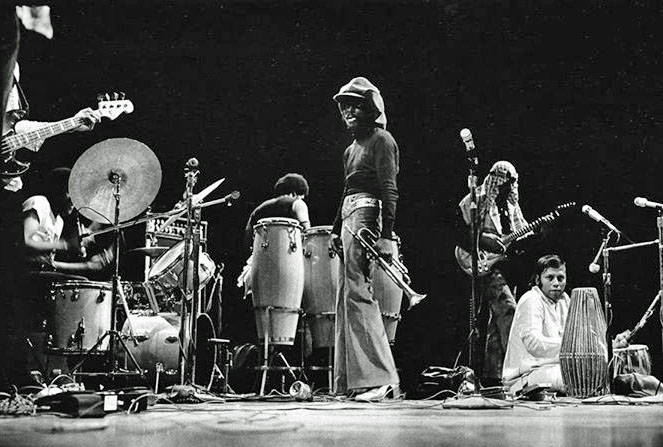

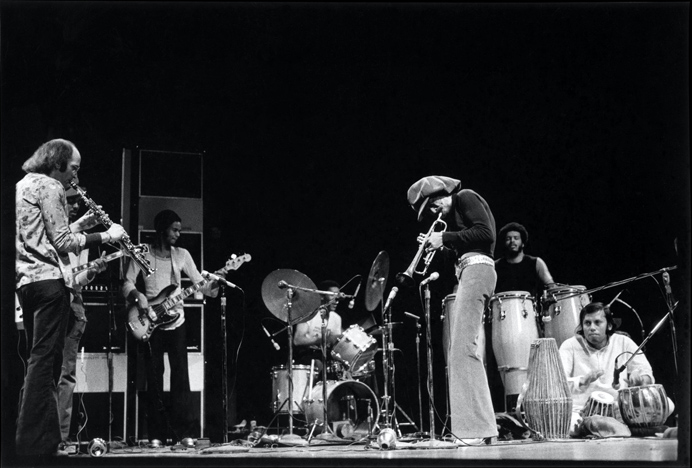

RAVI SHANKAR

Ravi Shankar performed on January 17, 1968, to an audience of about 1,500 – about 200 beyond capacity, as chairs were set up on stage behind the performers. He was supported by Alla Rakha on tabla and a woman tamboura player.

The Walker Art Center planned a lecture-demonstration the evening before Ravi Shankar’s concert. The program about the Sitar and Sarod was presented by Tony Glover and J. Pease, “students of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan” at the Walker.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

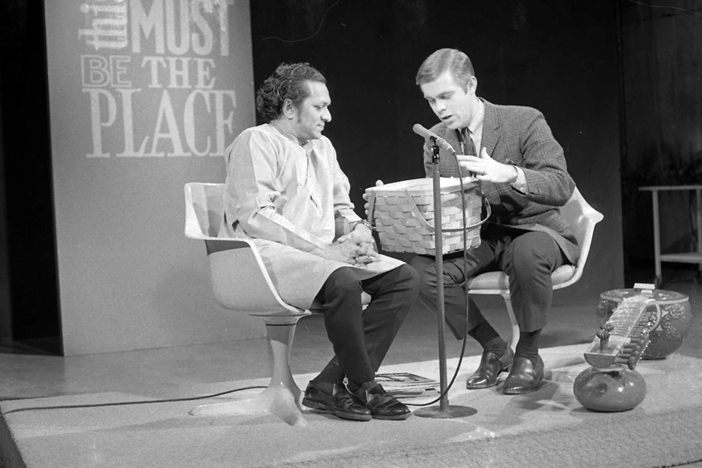

Either before or after the show, Shankar appeared on Bill Carlson’s show “This Must be the Place.”

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Where magazine wrote that Shankar had left his brother’s famous dance company at age 17, where he was a star dancer, to renouse all worldly posessions and retreat t a small central Indian town to master the art of playing the sitar. After 7 1/2 years of constant practice, he began his determined mission to bring Indian music to Western audiences. Raga was enjoying an ever-growing popularity in the U.S., especially because of it by the Beatles and other rock groups.

Peter Altman of the Star noted that Shankar was voted “scenemaker of the year” in the annual Pop Eye poll of the Village Voice, and the entire “in crowd” of the Twin Cities was out in full force to see the genius of the sitar in his first local appearance. Altman deemed the performance “part brilliant artistry, part extension-division course in Oriental music, and part hip milieu.” Shankar provided copious and relatively coherent explanations of the theories behind Indian classic music, the structural elements in sitar and tabla improvisation, and the principles of Indian harmonics.

The audience came dressed in saris, Mao suits, hip-high boots, and brightly painted neckties, and Altman said they would have come away infatuated had Shankar played 653 choruses of “Three Blind Mice.” But what he did play was five pieces: an opening sitar solo, and then the long second piece involving conversation with the tabla, supported by the background of the tamoura. After intermission there was a tabla solo, another sitar solo and a second ensemble piece.

Allan Holbert of the Tribune noted that the ragas began slowly and thoughtfully, then developed into wild, swinging, entrancing climaxes. In the final number, the melodic and rhythmic action was traded back and forth between the sitar and the tabla. Holbert concluded his review with “An evening of sitar music is an exotic place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there every Friday night.”

JUDY COLLINS

Judy Collins performed on February 18, 1968, presented by the Walker.

She was supported by Bill Lee on bass, and Paul Harris on electric organ. Miss Collins occasionally played piano.

Collins left Peter Altman of the Star speechless, saying she makes her listener wish that he were a better person. The headline of his review read “Judy Collins Exposes Her Soul and All its Anguish.” Further into his review, he says, “She has a golden alto, breath control and vocal range that outdistance any of her rivals.”

Allan Holbert of the Tribune wrote that Collins’ material – mostly about love and war – could be called contemporary folk music, presented simply and with very little physical mostion, but with great emotional intensity.

JAZZ AT THE GUTHRIE ’68

The Walker Art Center presented another Jazz at the Guthrie series in the Spring of 1968.

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

CHARLES LLOYD

The Charles Lloyd Quartet performed on April 7, 1968, presented by the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

Lloyd’s Quartet included Keith Jarrett on piano, Ron McClure on bass, and Paul Motian on drums. Lloyd played tenor sax and flute

This concert was only three days after Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated, but thankfully Minneapolis was spared violent protests and it was determined that the concert would go on. There was no mention of Dr. King at the concert, reported Allen Holbert of the Tribune.

Holbert described Lloyd’s music as “wild, far-out jazz that has been described as ‘post avant garde.'”

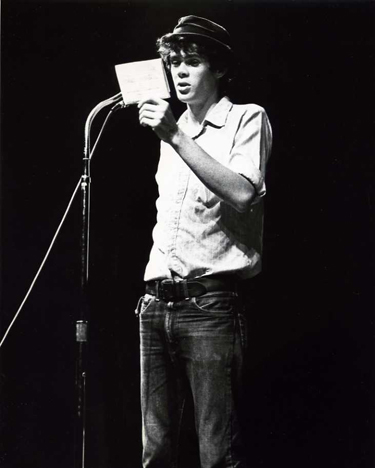

ARLO GUTHRIE

Arlo Guthrie performed on April 20, 1968, in a show sponsored by the Walker.

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

Peter Altman of the Star noted that the audience for this show was young and overappreciative of the talent of Guthrie. Altman found Guthrie to be funny and ready to be an opening act, but not the star.

The obscure, sitar-flavored, semi-agonized singing lacked charm, individuality, life and impact. Guthrie’s flair is for comedy – droll, slow, anti-authority comedy – and he should stick to it… I found his concert dull and misdirected. For a short program, it was too long.

JAZZ ’68

GARY BURTON

The Gary Burton Quartet performed on April 28, 1968, presented by the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

Burton was formerly a sideman with George Shearing and Stan Getz, and his group’s sound was described jazz/rock, a new sound in the jazz field. Burton played the vibraharp (vibes), and his group was Larry Coryell on electric guitar, Steve Swallow on bass, and Bob Moses on drums. (Where magazine, April 27, 1968)

Allan Holbert of the Tribune wrote that Burton’s jazz, based mostly on original tunes, required more than one hearing to be fully appreciated. The result of the music is fascinating, but not easy to comprehend.

MILES DAVIS

The Miles Davis Quintet performed two concerts on May 26, 1968, presented by the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

Davis’s backup musicians were Wayne Shorter on tenor sax, Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, and Tony Williams on drums. Davis played trumpet.

Peter Altman of the Star called Davis “supercool and hypertense at the same time,” walking offstage whenever he wasn’t playing. He performed one number before intermission and three nonstop afterwards afterwards, for a total of 1 3/4 hours of playing time.

MOSE ALLISON

The Mose Allison Trio performed on June 23, 1968, presented by the Walker’s “Jazz at the Guthrie” series.

Allison performed with two sidemen: Pete Magadini on drums, and Walt Booker on bass.

Allan Holbert of the Tribune explained that Allison was a white man from Tippo, Mississippi who sounded black. At the beginning of each half of the concert, Allison did some straight piano instrumentals. “He has a voice like a lazy, velvet – toned, tenor saxophone.” Holbert wrote that Allison’s jazz wasn’t avant garde, or even modern. “But it was melodic without being repetitious and it makes you want to listen and it makes you want to move.”

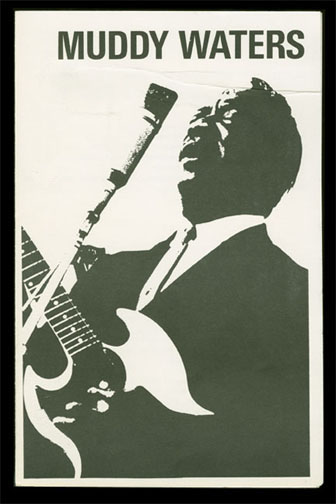

MUDDY WATERS

Muddy Waters and his Band performed on July 14, 1968, presented by the Walker. See an ad on Robb Henry’s blog.

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

Muddy Waters (guitar and vocals), Otis Spann (piano and vocals), Sammy Langhorn (lead guitar), Luther “Georgia Boy” Johnson (bass and vocals), S.P. Larrie (drums), Paul Oscher (harp).

Tom Scanlan of the Star wrote that Waters and his band blew the roof of the Guthrie. Waters opened with a half dozen slow, intense numbers from the 1940s and ’50s before turning over the rest of the first set to his rock band. In the second half, Waters returned to do three numbers, using “weird chords and odd jumps … at once more old-fashouned and farther out than anybody on stage.” Then Otis Spann took over.

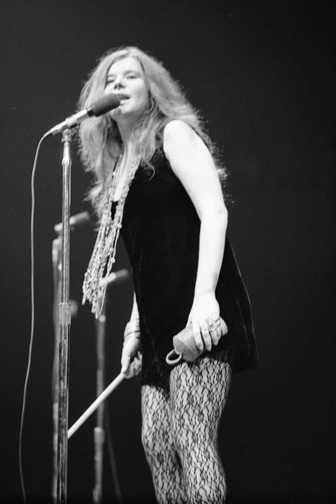

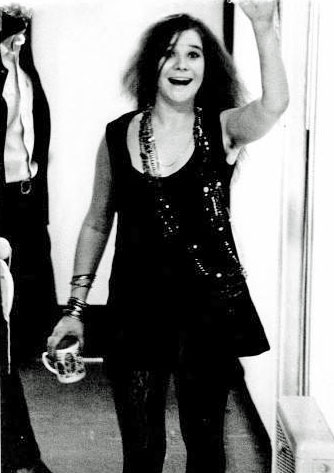

JANIS JOPLIN

Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company performed on August 18, 1968, presented by the Walker. The date had been changed from August 11.

Janis was 25 years old at the time, and had been with Big Brother since 1966. Members were Peter Albin on bass, David Getz on drums, James Gurley and Sam Andrew on guitars. The group’s LP “Cheap Thrills” had just been released that month.

The Promo in Where magazine is slightly amusing:

Another folk-rock group, this one from the West Coast, performs at the Guthrie Theater Sunday, August 18. Big Brother and the Holding Company, a four-man and one-woman group, is being sponsored by the Walker Art Center. The woman of the group is 25-year-old Janis Joplin, a Texan who is considered the top while blues singer today. She joined the Big Brother group when it was formed in 1965. The five project the emotions about which they are singing with a power that has nearly mesmerized audiences. The present an exciting combination of blues, rock, folk and spiritual rhythms from the irreverent to the zany, with a good measure of humor. (August 1968)

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Janis waves as she leaves the building. Mike says the photo below was the last frame on the roll, accounting for her fingers being cut off. Also, there was (of course) Southern Comfort in her cup.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Allan Holbert of the Tribune didn’t like the volume or the talent of the band, but he deemed Janis “an exceptionally talented performer. She has stage presence bursting out all over the place. Really confident. She bumps and grinds like and kind of a young Mae West. She has a fantastic voice that will do about anything for her, although she does seem to mistreat it.” He compares her performance to a minstrel show, where, instead of using black face, she uses black voice.

Daniel Marston of the Star was quite descriptive of her performance:

Janis sang, screamed, stomped, pleaded, and cried, holding the audience in a spell until the last cooing syllable – and thunderous, cathartic, ear-splitting crescendo. The concert felt like a baptism, like a rite of purification and cleansing.

Somewhere I read that Big Brother noted that it was the first time they had played in a theater venue with no light show and no dancing, but I have no citation for this.

DOC WATSON

Doc Watson performed on September 15, 1968, presented by the Walker. He was accompanied by his son Merle.

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

Peter Altman’s review in the Star reveals that Watson was a blind guitarist and singer from North Carolina. He was a scholar of folk and bluegrass music, tracing the histories of songs as far back as Elizabethan England. The first half of the program was dedicated to old-time music. After intermission he played songs by popular country singers.

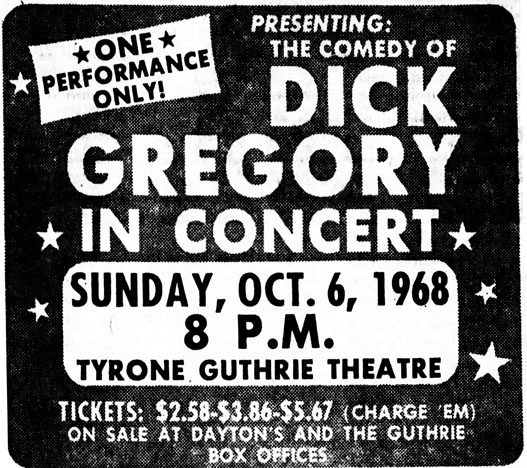

DICK GREGORY – CANCELLED

Dick Gregory was scheduled to appear on October 6, 1968, sponsored by the Institute of Afro-American Studies. The appearance was cancelled because too few tickets were purchased.

Minneapolis Tribune, September 1968

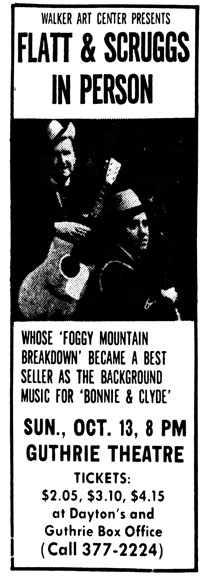

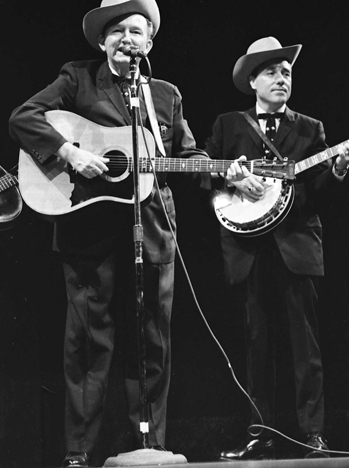

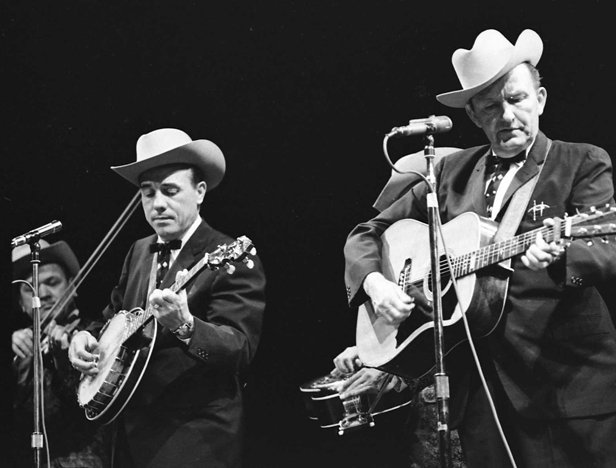

FLATT AND SCRUGGS

Flatt and Scruggs, with the Foggy Mountain Boys, performed on October 13, 1968, presented by the Walker.

Minneapolis Star, September 1968

Flatt and Scruggs – Photo copyright Mike Barich

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Daniel Marston’s review in the Star called Flatt & Scrugg’s music “fast and friendly,” and their humor refreshing. They played their most famous song, the Theme from the Beverly Hillbillies” and presumably songs from the soundtrack of the film “Bonnie and Clyde.” They were accompanied by the Foggy Mountain Boys, who were not listed in the program.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA – DID NOT HAPPEN

There was one ad that the band The United States of America was to perform on October 20, 1968, presented by the Walker. But then no more was said about it. Wikipedia says that the band was seriously breaking up about this time.

Charles Helm wrote:

I’m a fan of this band and was surprised to see them listed in Walker’s own archival list of past shows. I dug out my CD reissue of their only album – the leader Joseph Byrd wrote extensive liner notes for this reissue that describe the very few live shows they played on the “tour” they attempted after the album came out. They only played three or four cities and Byrd described in detail each show in each town; most went badly. Minneapolis (and Guthrie) wasn’t one of the cities they played…they broke up after the tour. Guessing that a Guthrie date was, at some point in the works, hence the file on them or single ad listing but no one threw away the file when the gig didn’t come together or was cancelled.

ODETTA

Odetta performed on November 17, 1968, presented by the Walker.

Minneapolis Star, November 1968

Peter Altman of the Star wrote that Odetta’s music seemed dated, and when she tried to be more contemporary, she seemed to be contriving her act superficially. She still had her huge, deep voice. Disturbingly, Altman observed, “She talks, like many people nowadays, about love and togetherness, but one cannot ignore in her remarks an unadmitted undercurrent of racial hostility and resentment.”

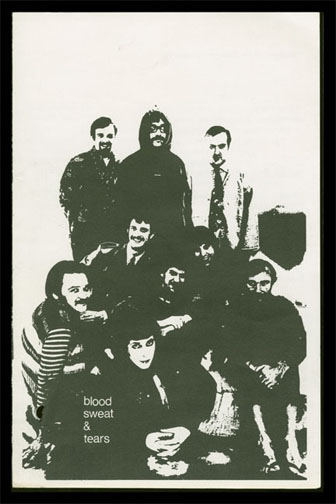

Blood, Sweat & Tears was originally scheduled for December 8, 1968, but the concert was postponed due to illness. The show was held on January 16, 1969.

1969

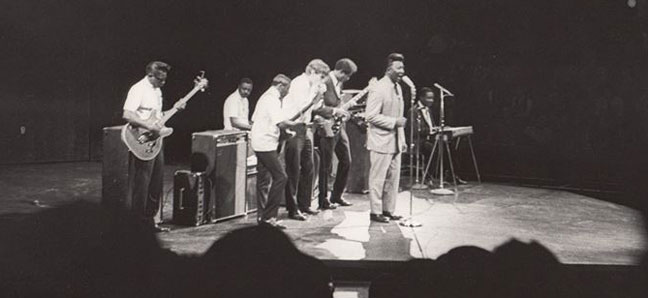

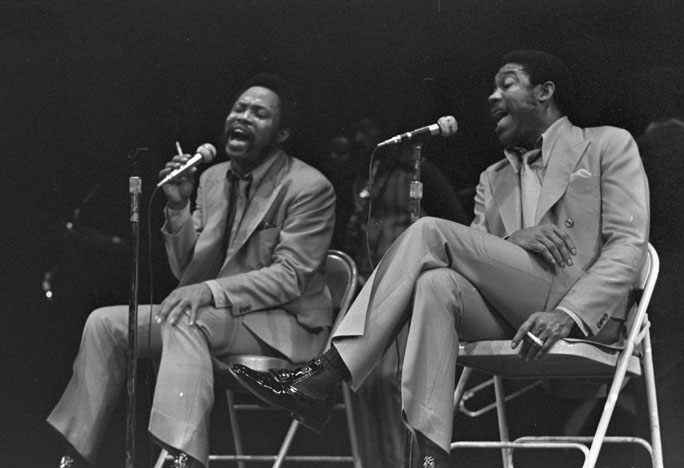

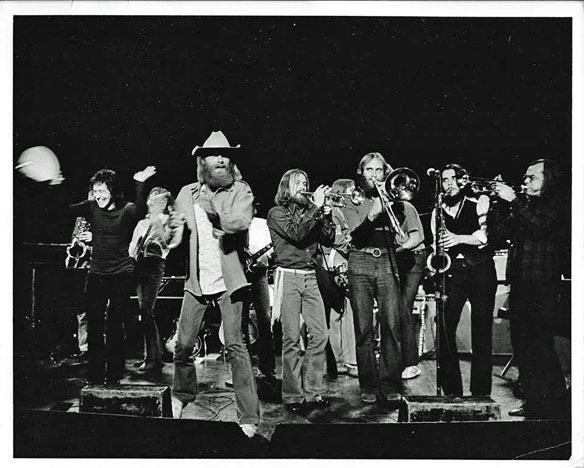

BLOOD, SWEAT & TEARS

Blood, Sweat & Tears appeared at the Guthrie on January 16, 1969, presented by the Walker.

Program Cover Courtesy Walker Art Center

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Their eponymous album came out that February. Warren Walsh: “I was disappointed as I expected the Al Kooper line-up but quickly forgave them when David Clayton-Thomas powered up.”

The show started almost an hour late, because one of their nine members – a trumpet player – couldn’t make it and they had to do a bit of extra rehearsing with a substitute. When it did start, the show lasted less than an hour. But reviewer Allan Holbert of the Tribune called it “one of the most exciting hours of music – classical, jazz, rock, or anything – that’s been heard around here in quite a while.” He was mightily impressed with Clayton-Thomas’s voice, which he thought sounded as black as can be. He noted that the sound wasn’t perfect because the group had to borrow local equipment for some of their own which was lost or broken in transit.

Peter Altman of the Star wasn’t as forgiving. The 45 minute wait to get in was “outrageous amateurism,” and the short show left their fans “disgruntled even more than waiting had.” The “noise” could have “drowned out an atomic explosion,” and when the whole band plays at once, it is a “deafening cacophony.” But all in all, those things could be overcome, and he saw much talent in several of the players, and wrote that the group’s music has “force, complexity, imagination, and soul. On a more professional occasion, I’d like to hear more.”

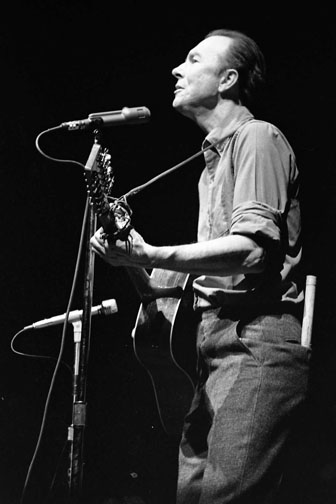

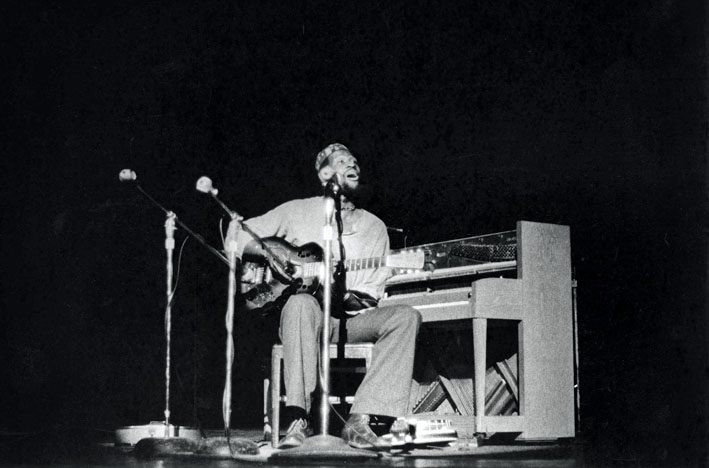

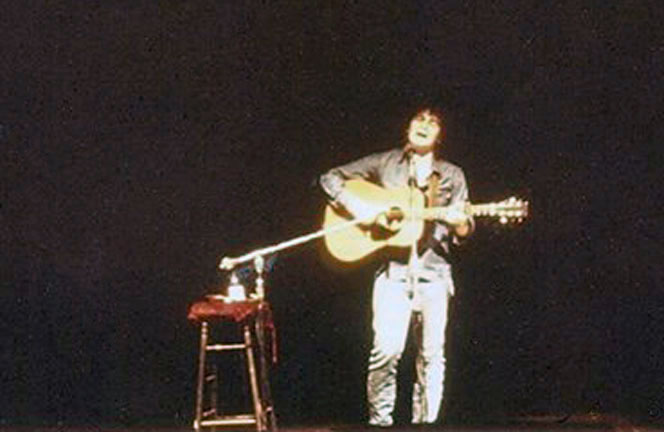

PETE SEEGER

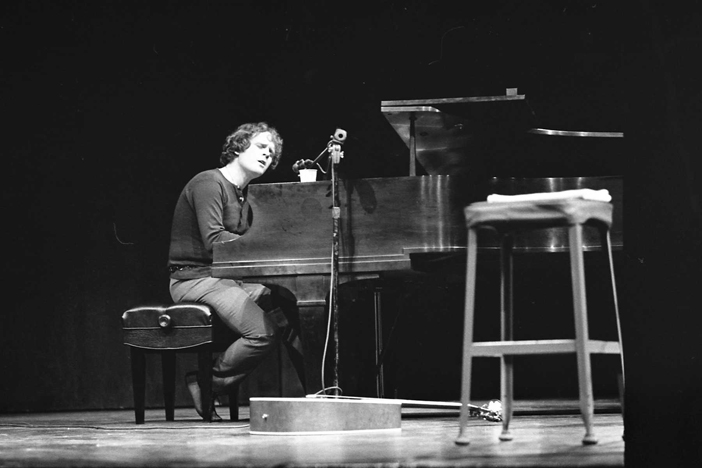

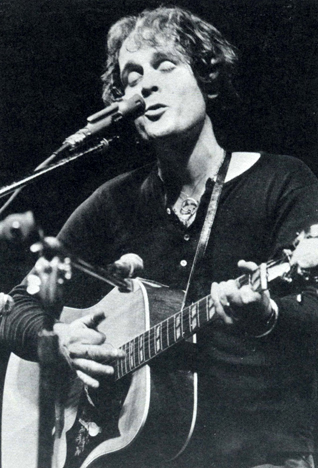

Pete Seeger performed on March 22, 1969, presented by the Walker. It was a sellout crowd, with overflow seating on the stage behind him.

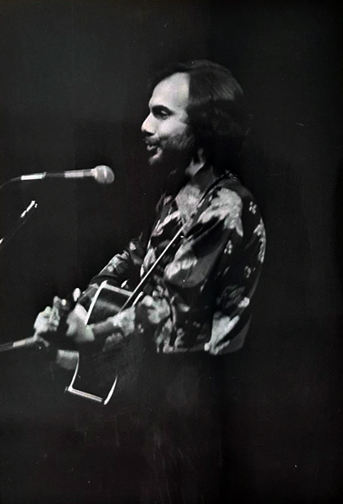

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Accompanying himself on the banjo or the 12-string guitar, Seeger ran the gamut of folk tunes, including love songs, protest songs, sing-a-long songs (not popular among shy Minnesotans), old songs, and his own songs. He moved from one side of the stage to the other in consideration of the people seated on the stage behind him.

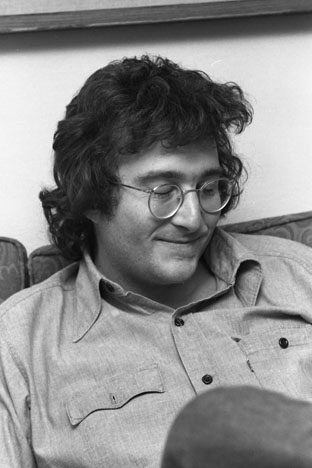

MICHAEL LESSAC

Local folk singer Michael Lessac, with Music Projection, performed on March 30, 1969.

Michael Lessac

Allan Holbert of the Tribune wrote that Lessac was a guitarist, singer, composer, and teller of not-always-funny stories. His songs and lyrics could be described as in an “urban folk style.” Lessac was once in the Metropolitan Opera children’s chorus and his father is a voice teacher. He was backed by Bill Perlman on guitar, Doug Kenny on electric bass, and Tony Glover, who played mouth harp on a couch the entire evening.

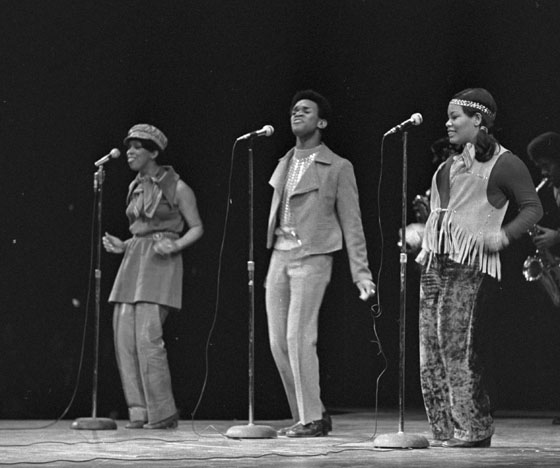

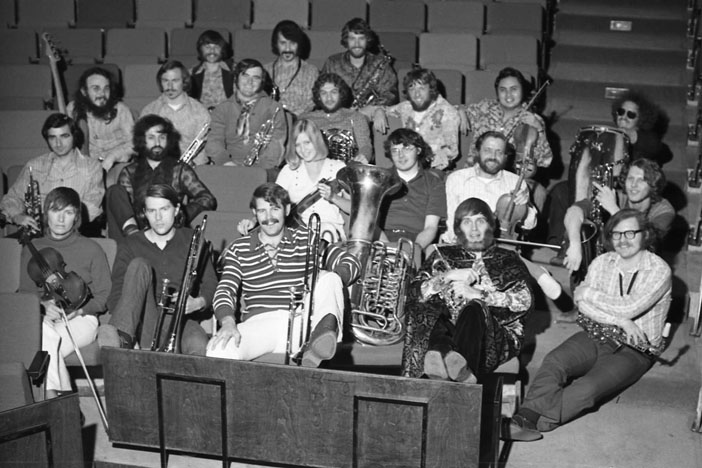

Music Projection

The warmup group was called the Music Projection – four guitarists, a drummer, and two girl singers who Holbert wrote did an excellent job.

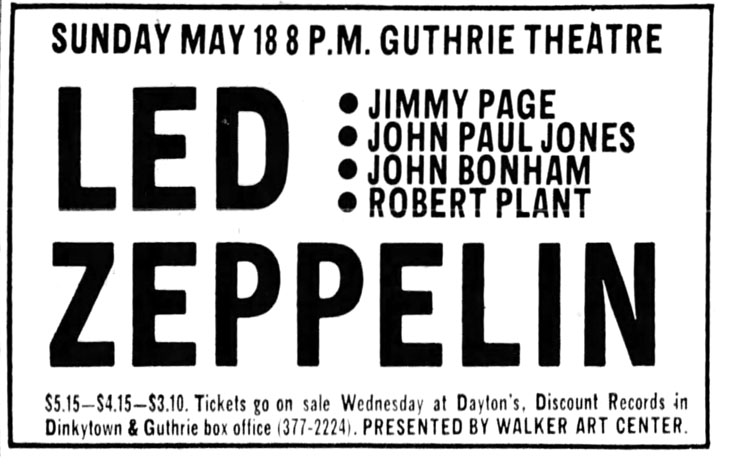

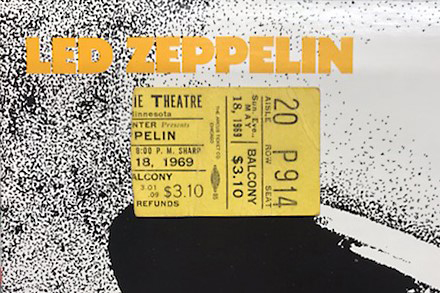

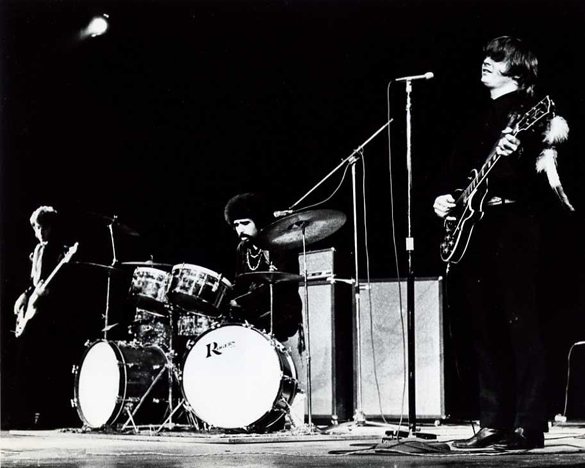

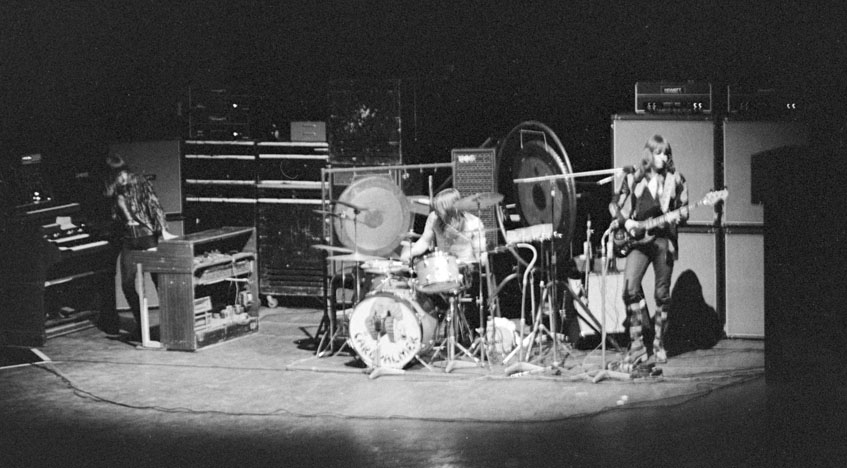

LED ZEPPELIN

Led Zepplin played the Guthrie on May 18, 1969, presented by the Walker.

Minneapolis Tribune, April 1969

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

The band started late; they had trouble with the borrowed equipment they had to use when their own PA system was damaged in transit. And reviewer Peter Altman of the Star complained about how loud it was. But this time it was Altman who said it was the the strongest music heard in the Guthrie in quite some time. “It revealed not just four players of extraordinary talent but a group which understood that ensemble playing implies communication and mutual stimulation among its members. And all seemed to respect the audience.”

The leader was guitar player Jimmy Page, formerly of the Yardbirds. The others were John Bonham on drums, John Paul Jones on bass, and singer Robert Plant, who Altman described as “a masculine Janis Joplin He tortures and strains his voice to communicate desperation, uncontrollable agony and delirious joy. Plant is overwhelming.”

It was reported to be an Amazing Show – they played for 2 1/2 hours with no opening act.

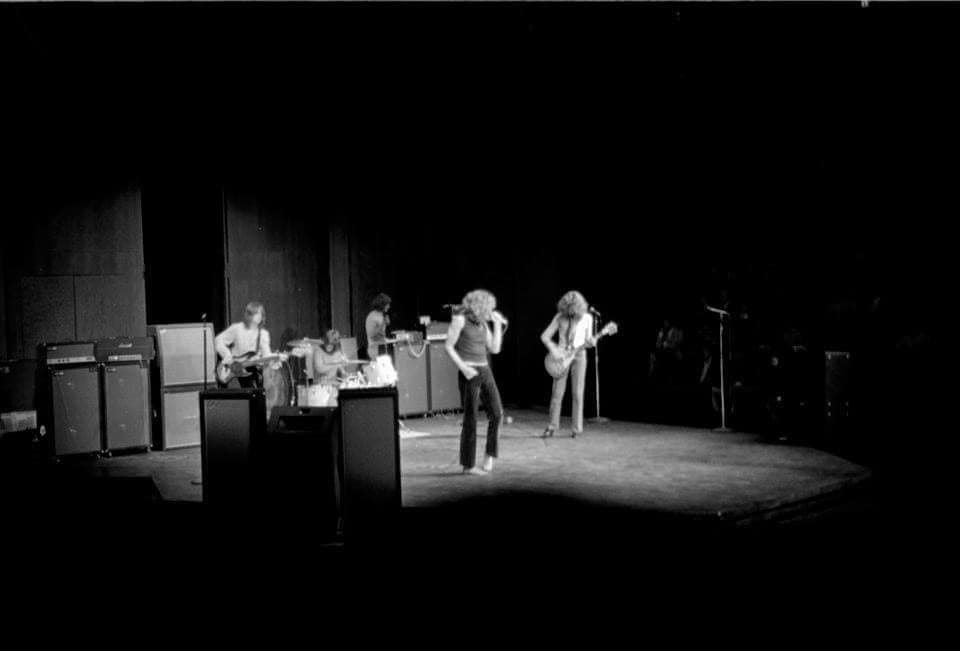

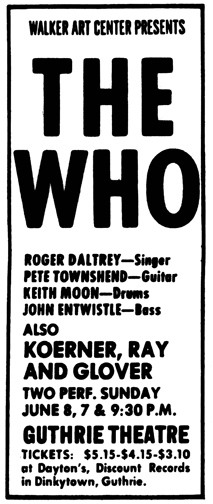

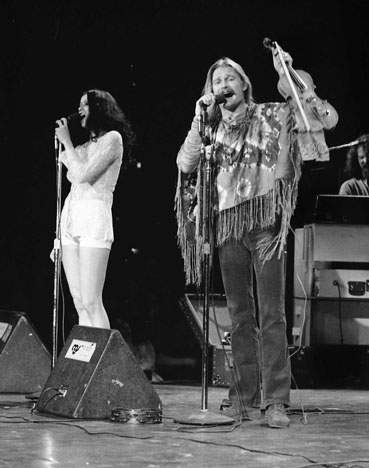

THE WHO

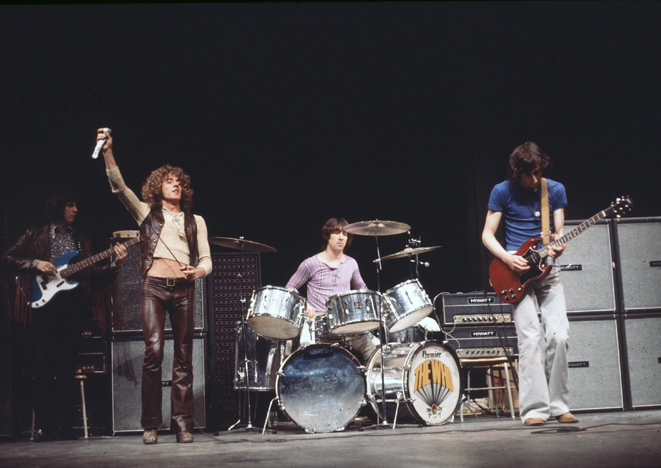

The Who, with Koerner, Ray, and Glover, played the Guthrie on June 8, 1969, presented by the Walker. It was shortly before Woodstock. They had to add a second show as the 7 pm show sold out immediately.

Minneapolis Star, June 1969

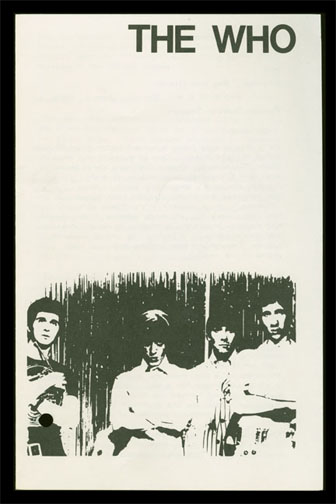

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

The Who

Photo copyright Mike Barich

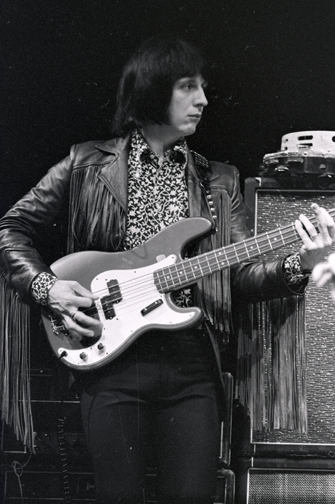

John Entwhistle playing amongst his fringe.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

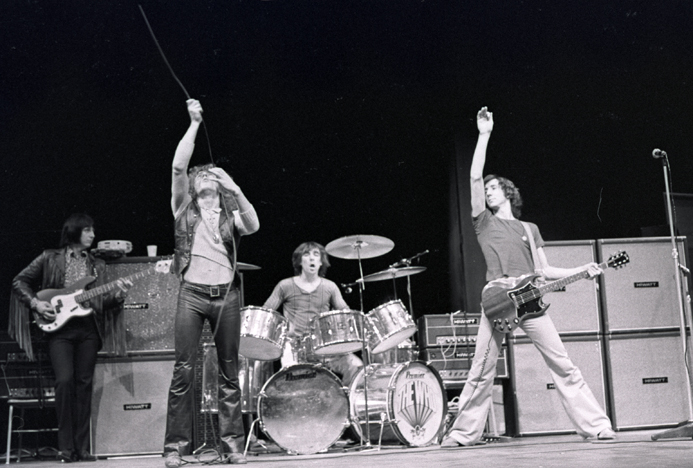

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Roger Daltry throwing the mike. Someone said he threw it halfway across the Guthrie audience.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Peter Townshend doing his signature jump.

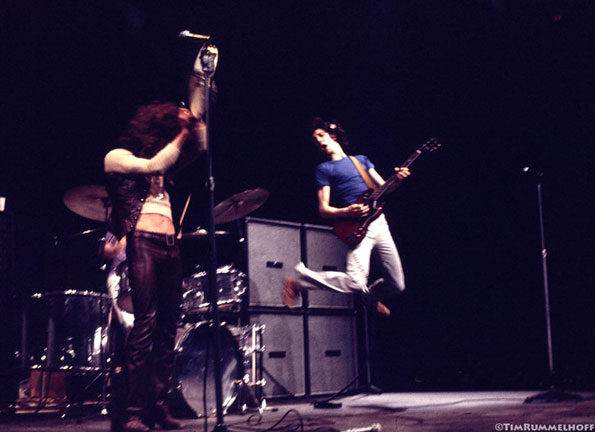

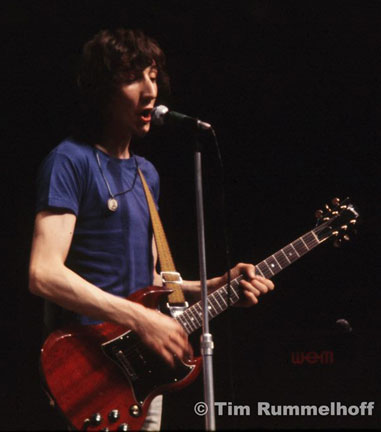

Photo copyright Tim Rummelhoff. No further use permitted

Photo copyright Tim Rummelhoff. No further use permitted

Photo copyright Tim Rummelhoff. No further use permitted

A review by Scott Bartell in the Tribune complained that the set he saw was only 45 minutes long. The first song was “Heaven and Hell,” and Bartell said that they exhibited “consistent strength, control and precision.” Bartell noted that Roger Daltry was frustrated by lack of room. “After that came about six short pieces from ‘Tommy,’ which had been released on May 23, 1969. The group went back to three old songs and ended very abruptly after a version of ‘Shakin’ All Over,’ leaving the audience unsure whether to go or stay… It was a concert worth hearing, but no one could be sure they had really heard a whole concert.”

The review in the Star, bylined by Kicky Sherman and John K. Sherman, Jr., focused on the volume, writing that the audience was “bombarded” by the sound: “Louder than a screaming jet, more powerful than a jack hammer, the Who assaulted, stunned, and delighted a largely young audience.”

Steven Adams remembered, “It was the only show I ever went to where someone in the audience asked the act to turn the volume down. Townshend refused. My ears rang for the next two days. Their ‘Live at Leeds’ album is nearly a song-for-song duplicate of their Guthrie concert.”

Party Crasher

The Insider reported that as the members of the Who smashed their equipment, “an impetuous boy who attempted to join in got as far as a couple of licks on the drum and guitar before a sideliner gave him the heave-ho. It was a dramatic ending to a bash of a concert.”

Gary Gimmestad reports:

Very near the end and leading up to the much-anticipated destruction and mayhem, Keith Moon slinked offstage while Townsend held focus. As the frenzy came to a fever pitch the floor trap opened and Moon rose out of the pit and circled back to his drums and the real destruction began. However, a stoner approached the stage, walking slowly toward Townsend with his arms outstretched. I don’t know what Townsend’s thinking was – “This guy is clearly whacked and potentially dangerous and I should just hand over the guitar,” or “What the hell, this could be interesting.” He did hand over the guitar and the energy was drained from the stage. It ended in anti-climax.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Koerner, Ray, and Glover

Tom Koerner, Tony Glover, and Dave Ray opening the show. Photo copyright Mike Barich

Tony Glover. Photo copyright Mike Barich

Koerner, Ray, and Glover opened the Who show and played for about an hour. It was the Guthrie debut for the trio, and Koerner told a dirty joke. Reviewer Bartell wrote that they were “not very well rehearsed but they still had their old feeling and kept a nice, steady beat.”

The Star review called the KR&G segment refreshing, and they were received warmly by the audience. They played songs from their early records and ended with the unaccompanied work song, “Linin’ Track.” The group had actually split up by this time, so this was a reunion of sorts for the trio.

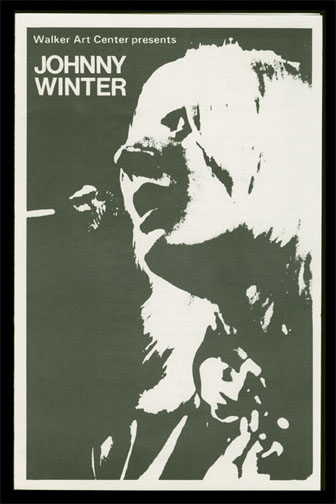

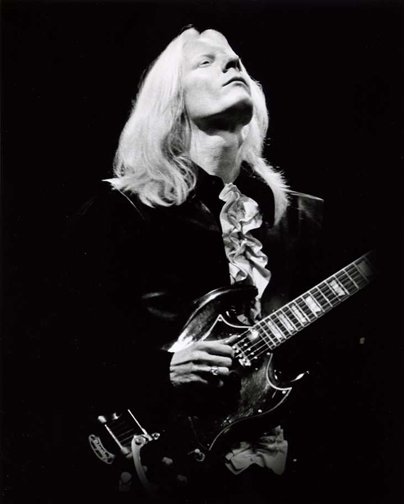

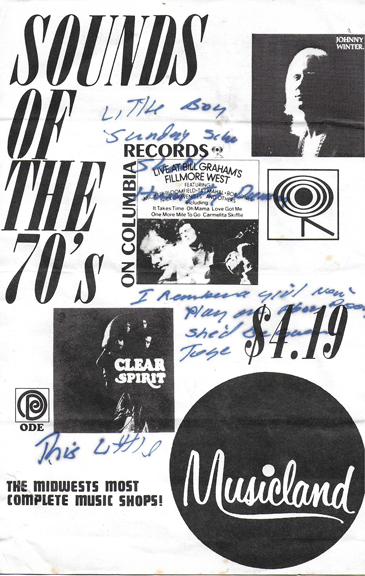

JOHNNY WINTER

Johnny Winter, with the Holy Modal Rounders, appeared on June 29, 1969, presented by the Walker.

Johnny Winter

It was Johnny’s first time in Minneapolis. See a poster on Robb Henry’s blog.

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Audience for the Johnny Winter show. Photo copyright Mike Barich

Things were getting looser at the Guthrie – despite a no smoking rule at the theater, Tribune reviewer Allan Holbert wrote that one could get high just breathing the air during the Johnny Winter concert. He deemed Winter and his band “quite sensational… Winter’s sensuous dancing and body pulsations are probably best appreciated by those in the audience to young to remember Elvis Presley in his formative years.”

Holy Modal Rounders

The Holy Modal Rounders featured Peter Stampfel on a green, electric fiddle and vocals. Holbert described their act as “put-ons of old songs and country-western stuff. I think they consider themselves more entertaining than they really are.”

Holy Modal Rounders – Photo copyright Mike Barich

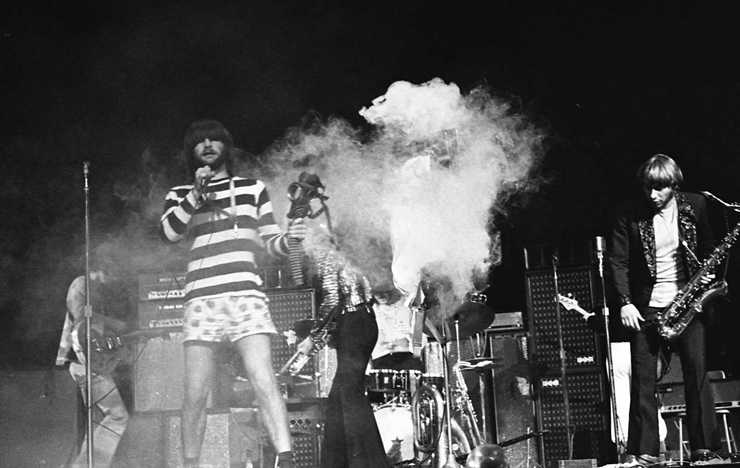

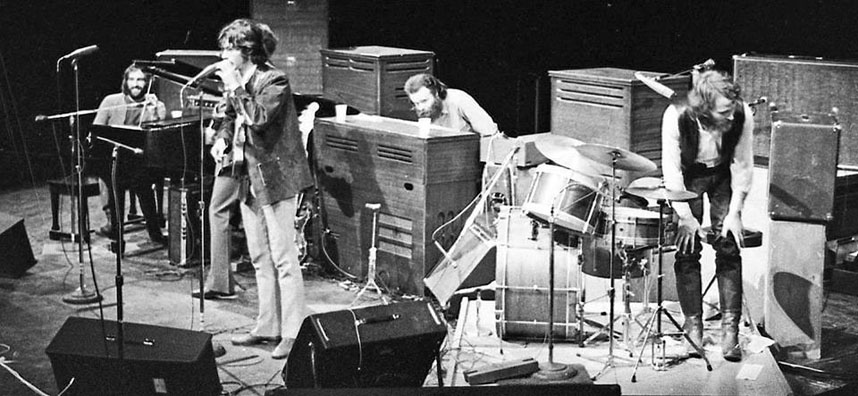

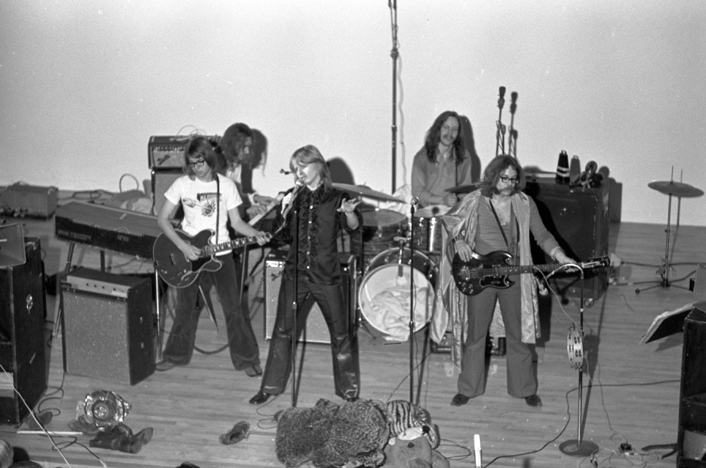

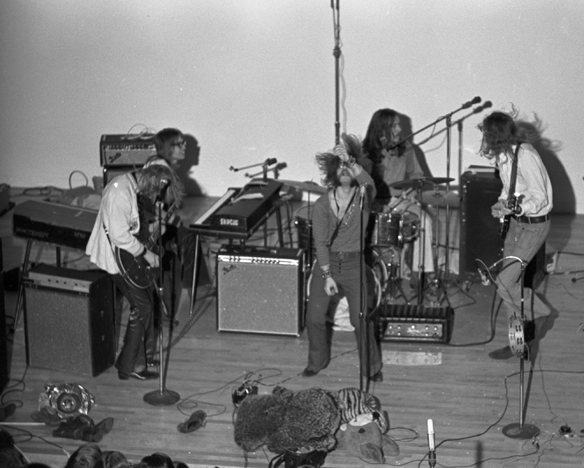

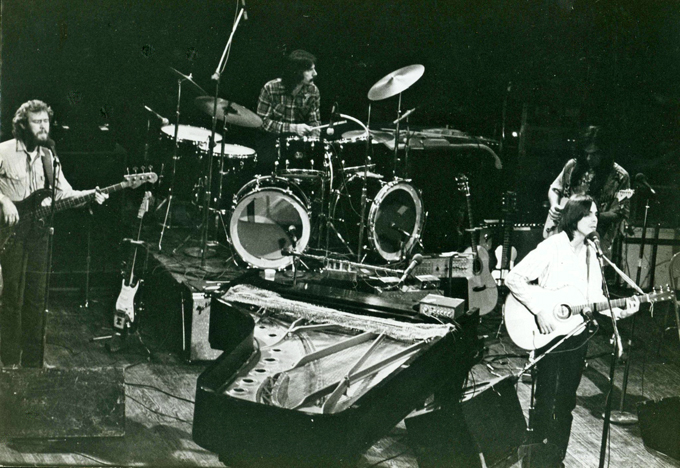

ZAPPA, COOPER

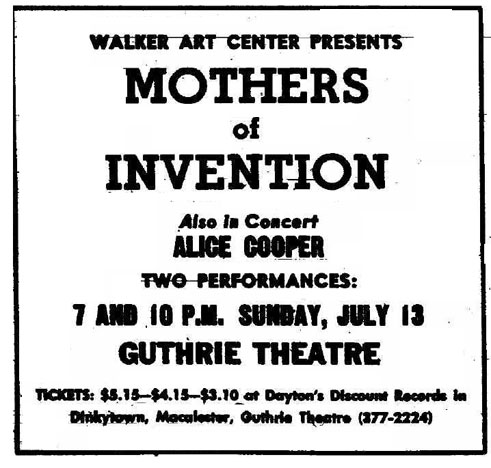

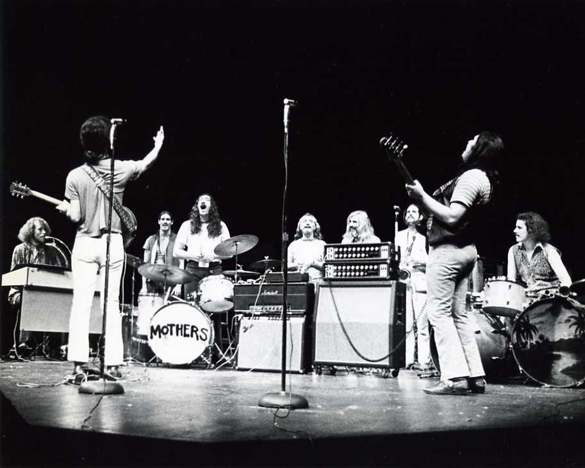

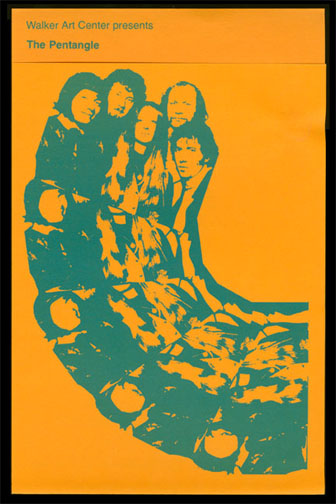

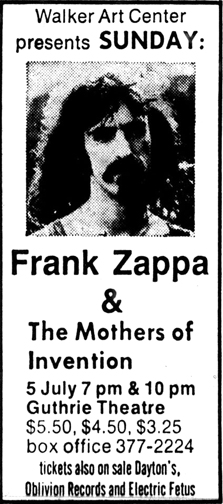

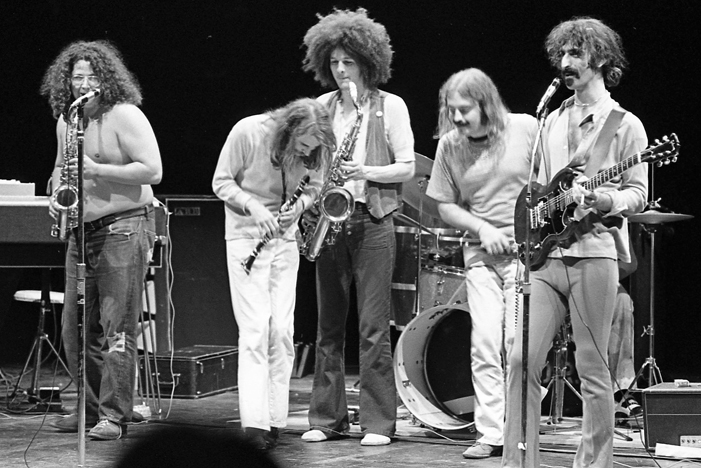

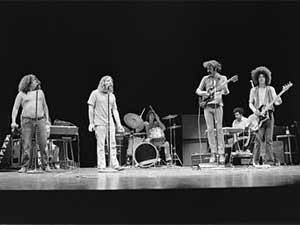

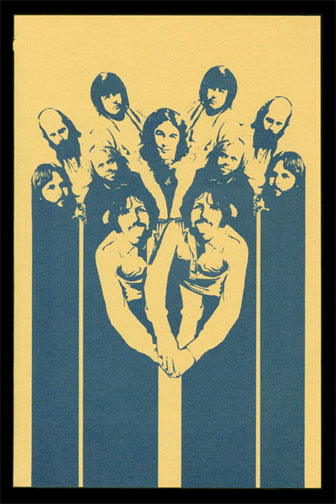

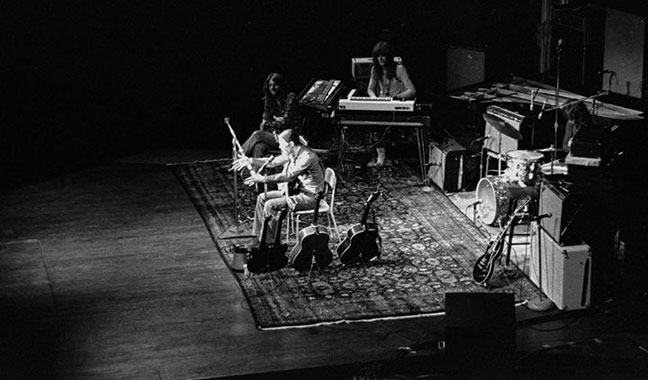

Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention (10 members) with Alice Cooper, performed two shows on July 13, 1969, presented by the Walker.

Frank Zappa

Ad from Minnesota Daily, courtesy Robb Henry

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

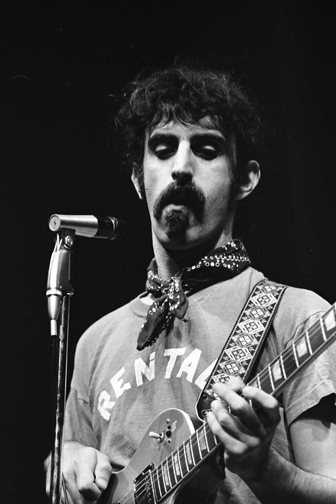

Frank Zappa photo copyright Mike Barich

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Mike Steele of the Tribune wrote that the depth and complexity, the subtlety and compelling richness of the Mothers’ music could only be appreciated in person, and the performance at the Guthrie “musically tore the place apart.” The music defies categorization, and the band includes some of the finest musicians in the business, including leader Frank Zappa, who was called the great musical satirist of the day. The concert was deemed fantastic and exciting, with songs that were few but long.

Reportedly the Zappa show featured mostly instrumentals as it was before Flo and Eddie joined.

Alice Cooper

Alice Cooper was a Zappa discovery and had yet to release their first album. Reviewer Steele called them five gaunt maniacs who were into some very heavy music and some extraordinary theatrics. Their act was part rock group, part performance art, and it was so loud that the words were drowned out, but the performance was entertaining.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Alice Cooper backstage. Photo copyright Mike Barich

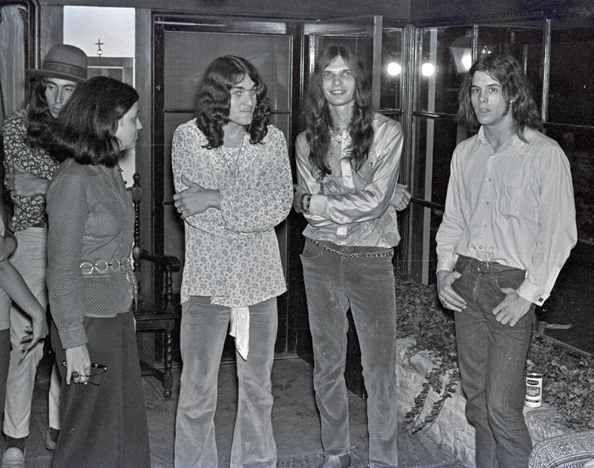

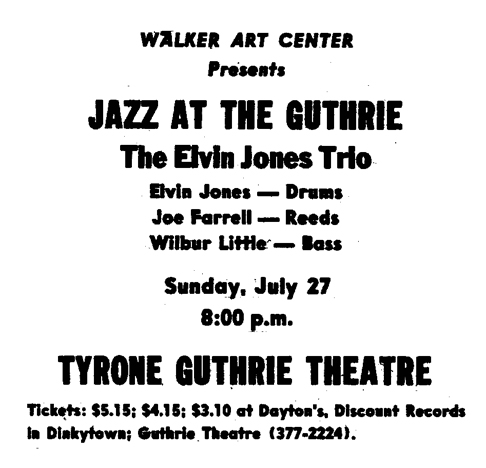

ELVIN JONES

The Elvin Jones Trio performed on July 27, 1969, presented by the Walker as a “Jazz at the Guthrie” concert.

Ad from Minnesota Daily, courtesy Robb Henry

Elvin Jones Program Cover courtesy Walker Art Center

Jones was on drums, Joe Farrell on reeds, and Wilbur Little on bass.

Kicky Sherman of the Star reported that Jones performed to one of the most appreciative jazz audiences the Twin Cities has seen. The young audience gave the trio three standing ovations.

Allan Holbert of the Tribune wrote a different story. Although he said that Jones used to play with John Coltrane, he noted that the theater was half filled when the concert started, and many left at intermission. The problem?

The solos were far too long, much longer than merited by the material in them. The players, while working hard and with integrity, seemed much more interested in entertaining and impressing themselves than their audience.

FLEETWOOD MAC – CANCELLED

Fleetwood Mac was scheduled to appear on August 3, 1969, but on the day of the show the Minneapolis Tribune announced that the the show was cancelled, as was the entire tour. A telegram in the program file from their New York agent says “Having probles with Fleetwood Mac immigration.” At the time, members of the group were:

- Peter Green, guitar, vocals, harmonica

- Jeremy Spencer, guicar, vocals, piano

- John McVie, bass

- Mick Fleetwood, drums

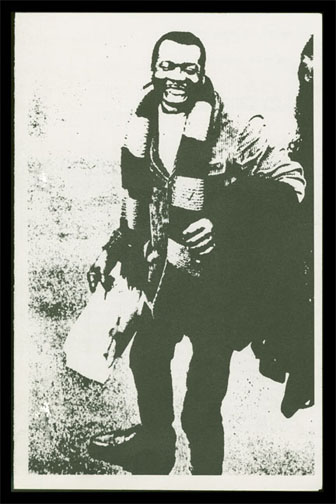

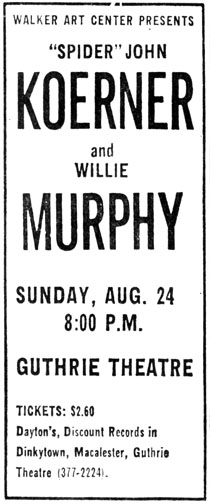

KOERNER & MURPHY

John Koerner and Willie Murphy performed on August 24, 1969, presented by the Walker.

Minneapolis Tribune, August 1969

John Koerner – Photo copyright Mike Barich

Carol Buckman’s review of this show in the Tribune starts out by saying that the stripper that Koerner and Murphy had planned to add to their show had to go, according to State law. So the show went on without her. The two were accompanied by two Frenchmen, she wrote: Bruce Menier, a stern-faced bass player, and Robert Grenier, a toothless drummer.

During the first half, Willie sat slumped over his piano, occasionally smiling through his thick red beard and long, wavy hair. After intermission, he “came out of his beard” and sent out lyrics of blues.

The two teamed up about two years before, and attracted an audience of mostly college freshmen and high school students wearing beads, beards, and granny gowns.

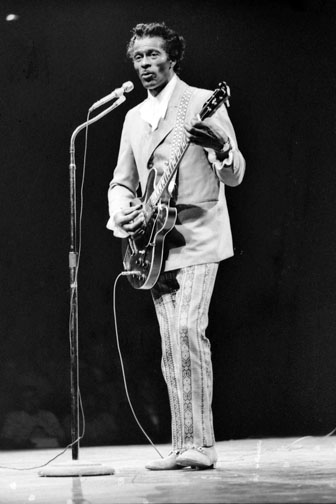

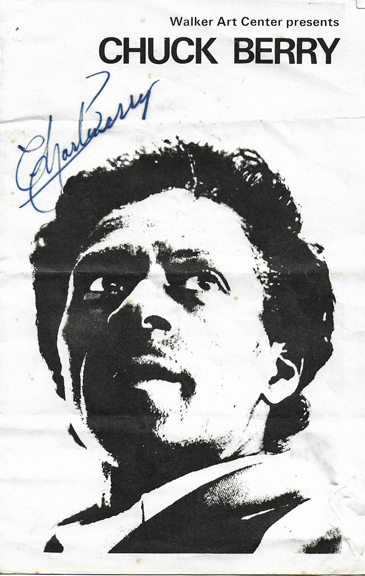

CHUCK BERRY

Chuck Berry, with Spider John Koerner and Willie Murphy, appeared on September 7, 1969, presented by the Walker.

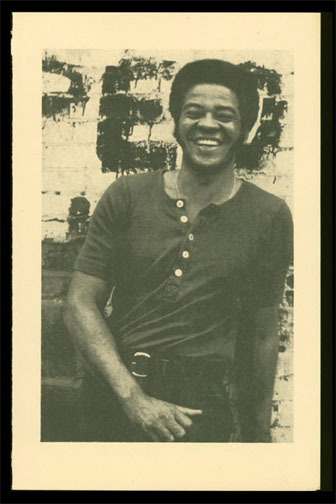

Photo copyright Mike Barich

The show was reviewed by U of M student Walter Lide for the Star, who reported that there were hardly any teenyboppers in sight. He also reported that his backup band “stank.” Berry is known for hiring local bands in the towns he plays and allowing little time for rehearsal. Also, Lide reported that, although Berry got a five-minute standing ovation, he did not return for an encore.

Sherwin Linton, our local country singer and teller of fantastic tales, has another wonderful story to share with us about meeting Chuck Berry during this stop in Minneapolis:

On September 7, 1969, I attended the concert by Chuck Berry sponsored by the Walker Arts Center at the Tyrone Guthrie Theater. Chuck came out onto the stage for a few minutes past the starting time and announced that the show would be opening in a few minutes, as soon as some business was settled. I assume he was demanding to be paid in cash prior to performing. He then returned to the stage. I believe there was an opening act which must have been Spider John Koener and Willie Murphy. I was not familiar with them at that time. As I recall three musicians waited on stage, bass, drums and guitar.

When Chuck returned he went into his opening song and very soon realized the back-up musicians were not familiar with his music and turned to them and told them they did not need to play. He did the whole show, just himself and his guitar. He introduced the song “My Ding-a-ling,” which he had not yet recorded. I wrote down some of the lyrics on my program and began performing it on my shows as a novelty song.

Following the show when I left the theater I saw Chuck walking toward Mt. Curve Ave. and caught up with him and asked if he would autograph my program. He said, “Are you with someone?” and I responded, “Yes, my wife.” He said, “I have to leave quickly, you can get into my car and ride to the corner and I’ll sign it and you can walk back.” He put his guitar and a briefcase into the car. I jumped in and he drove to the corner of Hennepin and signed the program Charles Berry. I thanked him and got out and returned to meet my wife at the theater.

I could not believe it, I had ridden with Chuck Berry. I have read so much about Chuck Berry and with the knowledge of what I have read I am even more amazed. Chuck Berry never trusted anyone. I have also been told it is very rare that he signed his name as Charles Berry. A highlight of his program was a narration of a poem he had written titled “My Dream,” which I have only found on one album, “San Francisco Dues.” His recorded version is six minutes and varies slightly from his live version of the Guthrie performance. I have seen Chuck Berry several times but meeting him, getting his autograph and riding in his car is an exceptionally special memory and highlight and this signed program is a treasure.

Front of program with autograph, courtesy Sherwin Linton

Back of program with song notes, courtesy Sherwin Linton

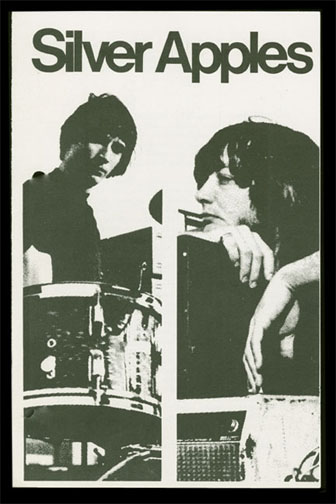

SILVER APPLES

Silver Apples appeared on October 5, 1969, presented by the Walker. The theater was less than half full.

Program Cover courtesy Walker Art Center

Silver Apples was made up of of a synthesizer named Simeon, the synthesizer’s inventor (Simeon Coxe III), and a drummer named Danny Taylor.

Mike Steele of the Tribune was unfulfilled:

First of all, Simeon was used in most of the group’s numbers as an organ would be, both for melody and bass. Only in a couple of numbers, the group’s best, did they pull the stops and use electronic music as electronic music with all its strange sound waves, oscillations, squeaks, squeals, wails and moans.

The other things a synthesizer does well involves multiple over-dubbing and sound effects – strange, new sounds that have been very effectively used with rock bands. But it’s almost impossible to get all those effects with one man running the machine trying to cover four instruments and sing as well.

Their concert has all the excitement of a drum solo, but all the dullness of an evening of nothing but drum solos.

Walter Lide of the Star was a little stunned. His review starts, “I saw them, but I really don’t believe them.” After much explanation, he wrote that the instrument sounds really good, and urged people to catch them next time around.

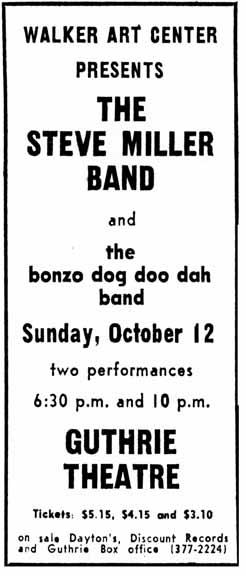

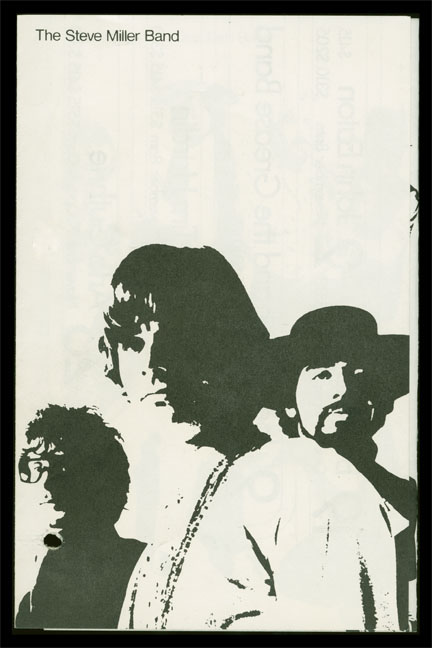

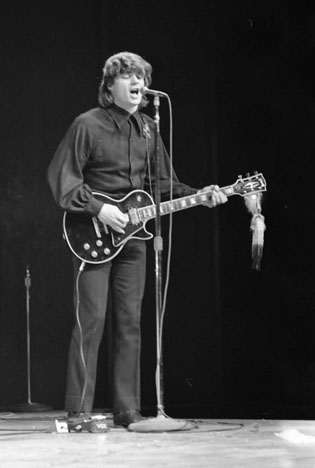

STEVE MILLER

The Steve Miller Band, with the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, appeared for two shows on October 12, 1969, presented by the Walker.

The Steve Miller Band

Minneapolis Tribune, October 1969

Program Cover courtesy Walker Art Center

Photo of Steve Miller copyright Mike Barich

Photo copyright Mike Barich

The Steve Miller Band consisted of Steve Miller, Tim Davis, and Lonnie Turner.

Marshall Fine’s review in the Star was hard on the band, calling it too derivative of songs by Cream, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, and others. Fine called them entertaining, but overshadowed by their opening act.

Allan Holbert’s review in the Tribune noted the Miller band’s excellent musicianship they used to produce a throbbing, hard-driving kind of rhythm and blues rock. He liked Miller’s harmonica playing better than his singing, but it improved when joined by drummer Tim Davis.

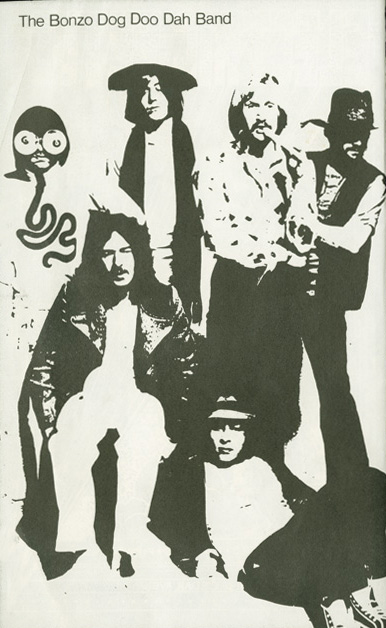

Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band

Program cover courtesy Walker Art Center

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Photo copyright Mike Barich

The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band started when they were all in art school together. Members were Vivien Stenshall, Neil Innes, Larry “Legs” Smith, Rodney Slater, Roger Spear, and Dennis Cowan.

Marshall Fine called the “Dog Band” “an English Mothers of Invention” that did old vaudeville routines during instrumental passages. They had weird machines that sprayed feathers and blew bubbles, and they executed well-done pantomimes. Group leader Vivien Stanshall picked his nose while imitating Elvis, and did a very graphic and funny impression of an overly-endowed stripper. From the pictures, underwear seems to be a key part of the show…

Holbert called the band “one of the craziest, most absurd and most entertaining rock type shows I’ve ever seen. What they have is kind of an English and updated version of the old Spike Jones band.” Holbert praised their musical abilities as well.

B.B. KING

The B.B. King Band appeared on October 19, 1969, presented by the Walker. The house was at capacity.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Reviewer Peter Altman of the Star reported that King’s concert was presented as if the Guthrie was a nightclub, with King providing comic commentary along with the music. He had a large, jazz-inclined band with three horns. The performance was deemed notable for musical traditionalism, personal warmth, and showmanship.

JOHN EATON

John Eaton and his Moog synthesizer appeared on November 2, 1969, presented by the Walker.

Eaton played an instrument called a Syn-ket, accompanied by Dick Bortolussi on drums and Clyde Anderson on bass.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Mike Steele of the Tribune called Eaton a member of the new generation of electronic composers, and the only performer who works live with the Syn-ket and the Moog Synthesizer. His music ranged from extremely cerebral compositions to jazz improvisations.

JOE COCKER

Joe Cocker and the Grease Band, opened by the Sons, performed on November 9, 1969. This was Cocker’s first Twin Cities appearance. It was a packed house.

Tony Glover himself reviewed the show for the Star, saying that nobody recognized Cocker at first since he had grown a wooly beard. He opened with “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window.” He also did “With a Little Help From my Friends” at the end, with an encore of “Delta Lady.”

The Grease Band consisted of Christ Stainton (piano and organ), Bruce Rowland (drums), Allen Spenner (bass), Henery McCullough (guitar), and Bobby Torres (occasional conga drums).

He returned on December 14, 1969 to perform at the Prison in Burnsville.

The Sons

The opening act for Joe Cocker and the Grease Band was a group called the Sons, formerly the Sons of Champlin. Members were Bill Champlin on bass and vocals; Terry Hagerty on lead guitar; Geoff Palmer on Keyboards, vocals, and saxophone; and Tim Cain on sax. They were based out of San Francisco.

Tony Glover called them a surprisingly tight and textured group, with a sound that was more cerebral than “gut-rock.” They had a good sense of timing and dynamics in their program of original material. Glover reported that the Sons got respectful if not ecstatic response from the crowd.

Mike Steele of the Tribune reported that the Sons were one of the tightest, most together groups he’d heard – no-nonsense, no-hype, perhaps not the best show band, but one of the best purveyors of rock to hit the Guthrie. Like Glover said, they weren’t overly loud.

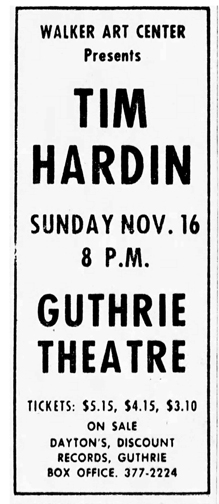

TIM HARDIN

Tim Hardin performed on November 16, 1969, presented by the Walker. The show was sold out.

Minneapolis Tribune, November 1969

Tim Hardin photo copyright Mike Barich

Tim Hardin photo copyright Mike Barich

Mike Steele of the Tribune wanted to like Tim Hardin – after all, he had written some great songs, but after a while he perceived that Hardin wasn’t working very hard to win his audience, and the concert had become dull and agonizingly indulgent and lazy. Even when the audience called for an encore, he didn’t perform his most famous composition, “If I Were a Carpenter,” but “rambled through a few bars of ‘Amen’ and walked off. The applause died down fast.” Steele continued, “his slurred bluesy voice obscured many of his lyrics and his lackadaisical attitude finally turned me off.”

What Steele saw as laziness, Peter Altman of the Star attributed to shyness. He characterized Hardin’s voice as “bleary” and his demeanor “frail” as he played his guitar. Altman figured Hardin was more of a songwriter than a performer.

ARLO GUTHRIE

Arlo Guthrie played two capacity shows on November 23, 1969, presented by the Walker.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

Peter Vaughan’s review for the Star said that Arlo was a much better storyteller than a singer, proven by his two monologues, peppered with words like “groovy,” “weird,” “man,” and “way out.”

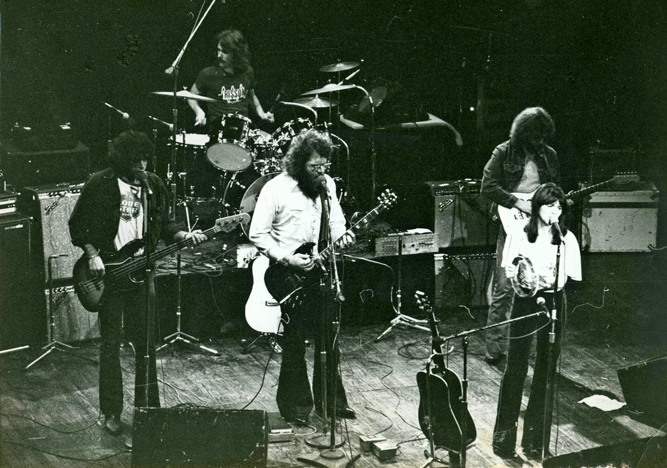

INCREDIBLE STRING BAND

The Incredible String Band performed on November 30, 1969, presented by the Walker.

Photo copyright Mike Barich

The band’s members were Robin Williamson and Mike Heron, two men from Scotland, and two young women identified only as Rose and Licorice.

Allan Holbert of the Tribune had a hard time thinking of something good to write in his review of this performance. They were having trouble with their sound system, making it impossible to hear the words to their songs. Plus he found the level of musicianship very low. The review was pretty harsh:

The band’s members don’t play in tune (in spite of the fact that they take years and ears to tune up). They do not play well together. None of them has much technical ability. Their songs are long, cutesy-folksy and repetitious.

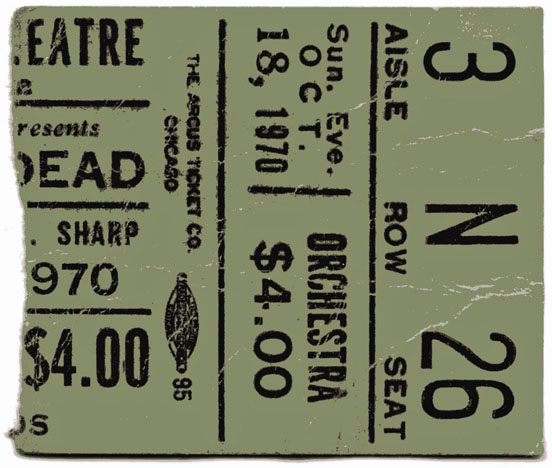

Holbert described how, after each song, they all got up and changed instruments. The musical high point, he said, was Williamson’s graphic description of how pigs make love…