Gay ’90s – Minneapolis

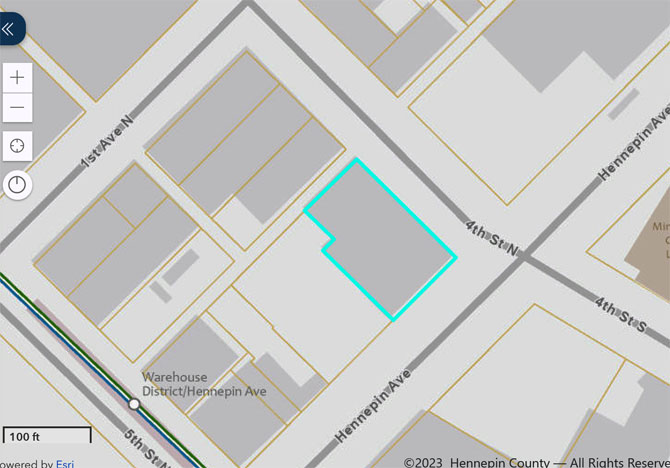

This page traces the most interesting history of the corner of 4th Street North and Hennepin Ave. in Downtown Minneapolis. This corner is difficult to describe, because the block is shaped like diamond if you place it north to south.

Map from Hennepin County Property Tax Database

The area highlighted in blue on the map above has been the home of some of Minneapolis’s most memorable music (and some non-music) venues. These include:

- The Casablanca Cafe

- The Gay ’90

- The Happy Hour Bar

- The High Life Spa

- The Indian Bar and Cafe/Indian Village

- The Mint

- Palace Restaurant

- The Paradise Cabaret

- Paradise Bar

- The Shanghai House

- Old Heidelberg Cafe

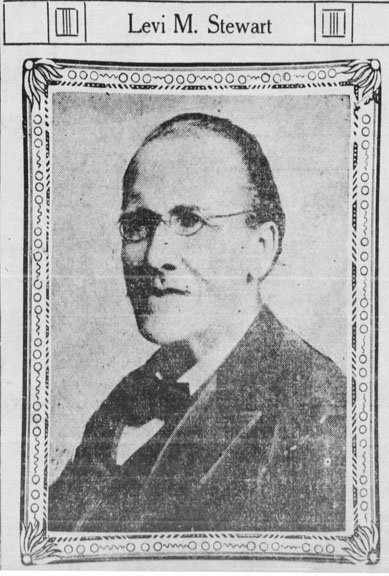

L.M. STEWART

Believe it or not, the corner of 4th and Hennepin, that would become the epicenter of the gay community in Minneapolis, originally belonged to a man named Levi Merrick (nicknamed “the Elder”) Stewart. Like many early settlers of the area, he was born in Maine, on December 10, 1827. Stewart was a Dartmouth-trained lawyer who came to town in 1856. He was a feisty millionaire, who had a proclivity for generating lawsuits and refusing to remove snow from his sidewalks during the winter. He was eccentric, often referring to his wife, while in fact he never married.

Minneapolis Tribune, May 4, 1910

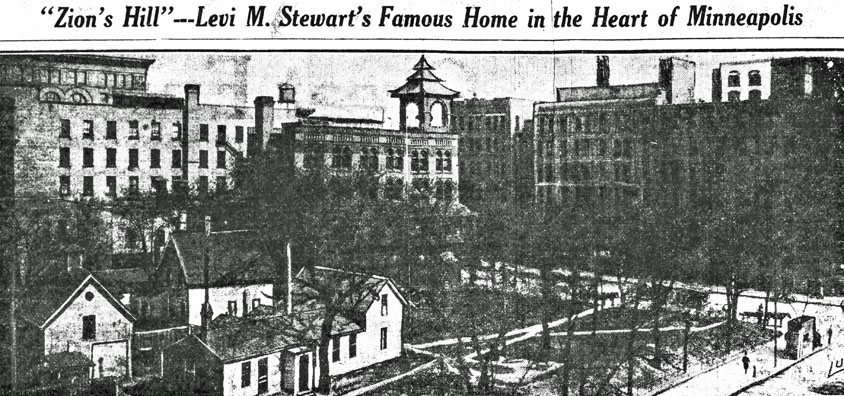

Stewart homesteaded the corner of 4th Street So. and Hennepin Ave. in 1862 – possibly 1870. He called it “Zion’s Hill” – perhaps a place of refuge. While Minneapolis grew around him, he was offered the equivalent of millions of dollars for his property “an eyesore” to some) for proposals that included a hotel or a hospital, But he was content to live in his little white house with the green shutters, saying that it was just too convenient to his office, which was in the Kasota Building, just across the street (now demolished). (Minneapolis Journal, September 27, 1901)

The caption on the photo below read:

Little white cottage where quaint old man lived and cut the grass regardless of enormous taxes and coming of such overshadowing neighbors as the Kasota Building and the structures of the Northwestern Fire and Marine, Wyman, Partridge, & Co., the Fire Department, and the Salvage Corps.

Minneapolis Journal, May 4, 1910

When Stewart died on May 3, 1910, the bulk of his estate went to his younger brother David, who still lived in Maine. (Minneapolis Journal, May 3, 1910) David died soon afterwards, but the land at 4th and Hennepin was eventually sold, as were most of Stewart’s other properties.

THE PALACE THEATER

The first building to go up on Stewart’s “Zion’s Hill” was not a hospital or a hotel, or even a palatial “Stewart Building” that he may have hoped for (Minneapolis Tribune, May 5, 1910), but a 2,700-seat theater. Please see THIS PAGE for information on the Palace Theater. The address of the Palace was generally consistently known as 414 Hennepin Ave. On City inspection cards it was known as 408 – 410 Hennepin Ave.

On the ground floor of the theater there were shops, such as the New Palace Coney Island and Percy Villa’s Sportland. (Percy Villa was a sports writer and a brother to Abe Percansky. Sportland was a pinball arcade.)

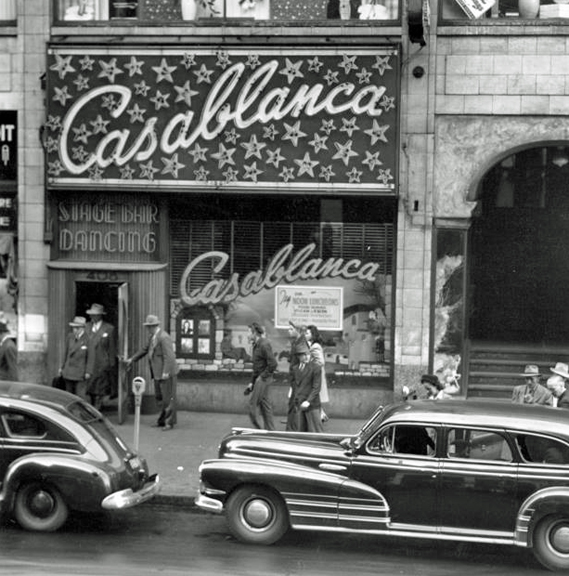

In the photo below, the Palace Theater is on the left. The photo must have been taken sometime between 1948 (when the Gay ’90s was established) and July 1953, when the theater was torn down.

Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

From permit cards it appears that Elder Stewart’s house was finally wrecked in about March 1918.

Records also show a 14 x 16 Pure Oil Station installed at that location in 1920.

1921

THE STEWART BUILDING

No, this isn’t really called the Stewart Building – Levi would be aghast at the thought of people drinking alcohol on Zion’s Hill, and even put it in his will that such a thing never happen, but lessees won the day. Instead of a grand monument to Elder Stewart, the building that appeared on his land was a two-story neo-strip mall, built in 1921, that could accommodate up to six storefronts, with addresses on Hennepin and also on North 4th Street. Pawn shops, bars, steam rooms, bars, mobbed-up joints, and bars were the hallmark of the Stewart Building. (I’m just making that name up, of course…)

Adding to the confusion is that the permit records show the address of the Palace Theater as 408-410, which is actually how the Stewart Building came to be known as.

One might wonder, as I did, why the building I’m calling the Stewart Building, on the corner of 4th and Hennepin, starts with 408 instead of 400. The answer is that the City permit records considered Stewart’s house to be at 400 – 406 Hennepin, which makes better sense.

Making the association of storefronts with addresses more difficult is that businesses have merged, the addresses have changed, and the newspapers have not been consistent when they report addresses.

I will divide the entertainment and some other venues in the Stewart Building into three parts, some of which are based on guesses:

- 408 Hennepin were businesses impossibly jumbled and which become the Gay ’90s since 1948. At the time the picture above was taken, all of the storefronts seemed to be used for separate businesses.

- 410 Hennepin is the storefront closest to the Theater/Parking Lot, and has been the Happy Hour Bar since the 1950s.

- 414 1/2 Hennepin is the basement of the Palace Theater, which hosted a great number of interesting (!) venues before meeting its doom in 1953.

408 HENNEPIN AVE.

What follows is an approximate chronology of three-fourths of the Stewart Building (gotta stop doing that), starting from the corner of 4th Street and running up to 410 Hennepin, where the Happy Hour Bar has been for many years. Because of the problems cited above, there will be overlaps, omissions, and gaps.

1930

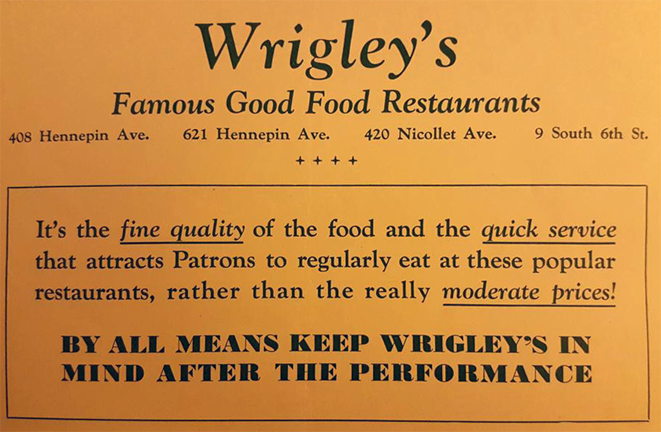

WRIGLEY’S

From the folks at Lyfmap we learn that in 1930, 408 Hennepin was one of four Wrigley’s “Famous Good Food Restaurants.” Funny how they had two locations on Hennepin Ave. that were just two blocks apart. In case you get hungry again? This ad obviously came from a program for a downtown show. A newspaper search finds this location extant from July 1922 to August 1932. Wrigley was R.B. Wrigley.

1930 image courtesy Lyfmap

1933

PALACE RESTAURANT

This dining establishment was found opening at 408 Hennepin in March 1933. It followed the Wrigley Restaurant. The last mention found was on November 14, 1933.

Minneapolis Star, March 14, 1933

1934

STEVEN’S LIQUOR STORE

This liquor store was also given the address 408 Hennepin, starting in March 1934. It was owned by Thomas M. Stevens, who was murdered in September 1934.

Minneapolis Star, March 21, 1934

1935

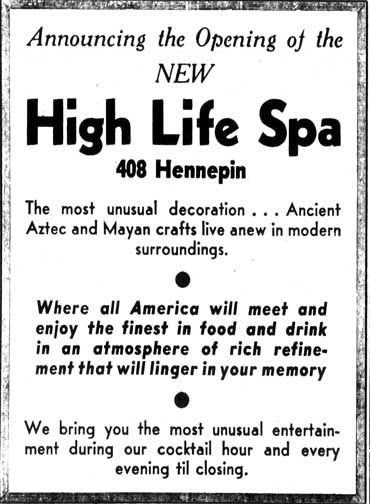

HIGH LIFE SPA

Not sure what this was, but the permit card says it was a beer parlor. It was owned by Frank Linehan, and references to it were found from December 1935 to March 1936. It closed in the summer of 1936.

Minneapolis Journal, December 26, 1935

1937

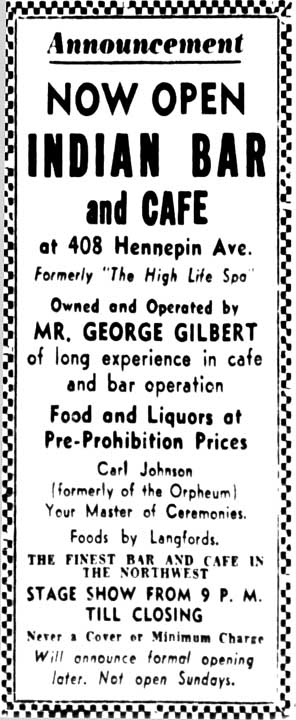

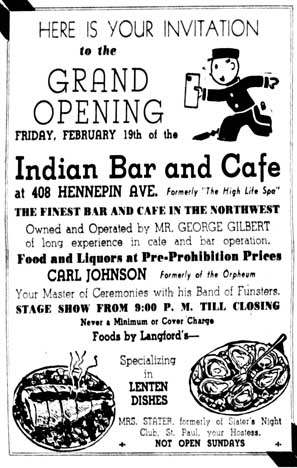

INDIAN BAR AND CAFE

This venue, also listed at 408 Hennepin, was around from February 1937 to March 1938. It was owned by John George Gilbert.

Minneapolis Tribune, February 14, 1937

Minneapolis Tribune, February 19, 1937

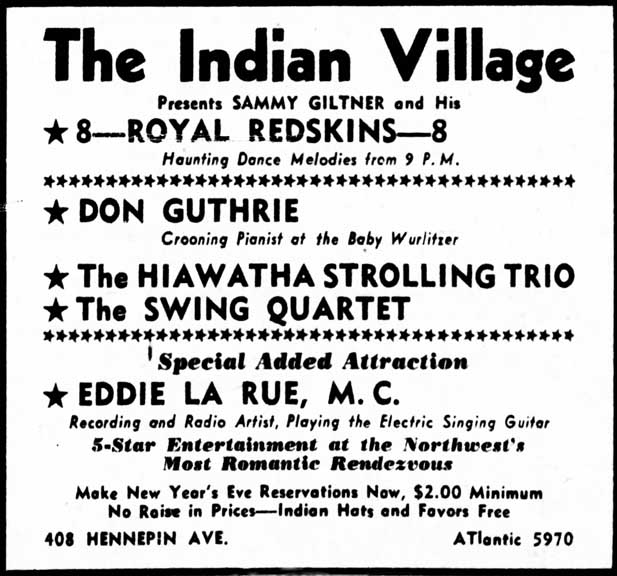

By the end of 1937 it had become known as the Indian Village.

Minneapolis Tribune, December 29, 1937

1943

THE CASABLANCA

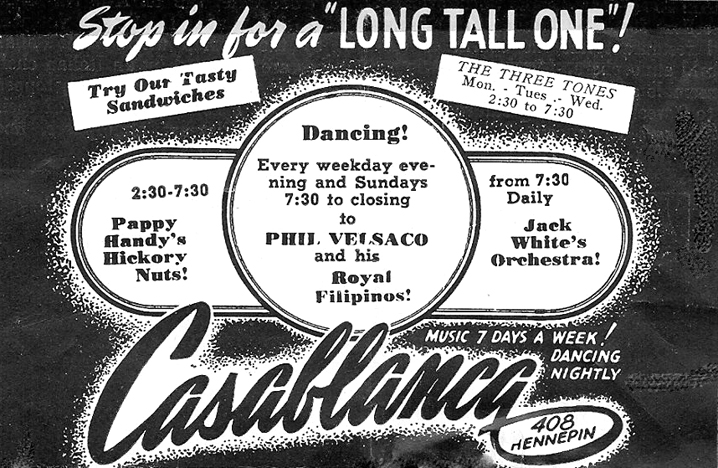

The Casablanca Victory Bar and Cafe (Stage-Bar-Dancing) opened at 408 Hennepin on April 5, 1943, in what had been a vacant building for a number of years.

The Casablanca was started by Herman Mitch, who had owned Mitch’s in Mendota. The War had forced him to lease out Mitch’s, and he opened the Casablanca with Matthew Willis. Gangster Tommy Banks loaned Mitch $31,000; $15,000 to start the bar plus money Mitch owed him for bootleg alcohol. Not all of it was repaid.

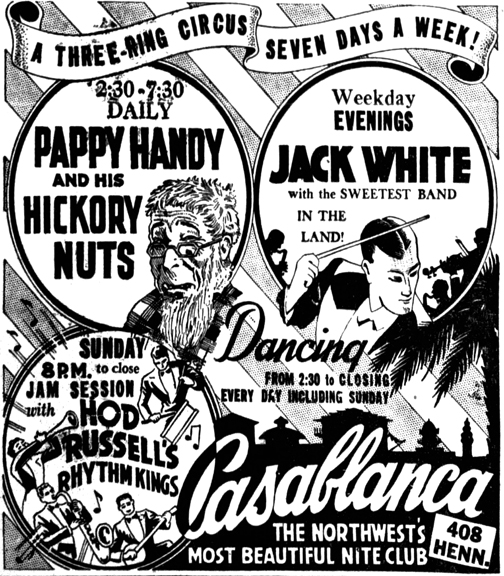

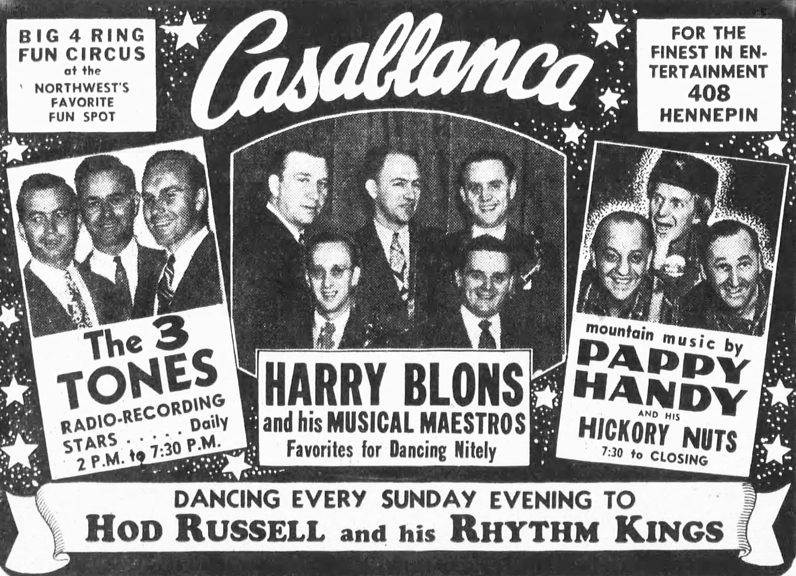

Mitch brought Red Dougherty from Mitch’s in Mendota with him, and the Casablanca offered Dixieland music to begin. The ad below from December 1943 seems to show that all sorts of music was available at the club.

Minneapolis Star, December 2, 1943

1945

1945 photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

MURDER AT THE CASABLANCA

On Friday morning, July 27, 1945, labor leader Albert Schneider, age 37, was killed by four gunshots in a shootout at the Casablanca. Schneider was an organizer for the General Drivers Union 544, AFL. Wayne Saunders (nee Rubin Shetsky), 39, the proprietor of the Casablanca, was charged with second degree murder. Gangster Tommy Banks was at the bar at the time of the shooting and was wanted for questioning. After the shooting Banks fled to his room at the Dyckman and then went “on the lam.”

While he was thinking things through, the local papers told of Tommy’s rise from a bellboy to a powerful underworld figure, “reported to be worth $400,000 to $500,000.” (Another article estimate his wealth as between $500,000 to $1 million.) He was also dubbed “Soft Touch Tommy” for his willingness to help out his friends with significant loans. As to his ownership of night spots, “A member of the liquor industry said Banks owns or has a share in, about 20 cafes or night clubs, or has in the past. They include some of the best known in town. But city and county records fail to show him listed as owner of any of the places.”

After three days, on July 30, 1945, he did come in to answer questions. The Tribune reported:

Banks gave his version of the events that led to the shooting. Saunders, Banks said, had attempted to persuade Schneider to leave the café after the closing hour, but Schneider refused. Banks said he kidded Schneider about his straw hat, then took Schneider’s hat and tossed it away. It landed on the floor and Schneider grabbed Banks’ hat and sailed it back of the bar.

Schneider then demanded that Banks buy him a new hat.

“Why should I?” Banks said he responded.

Saunders then intervened and again attempted to eject Schneider. Banks said Schneider struck Saunders in the side of the head and Saunders fell to the floor. Then shooting began. Banks said in the melee that resulted he was struck in the face and knocked to the floor.

Banks was vague in his statement as to details of the shooting. He said he did not actually see the shots fired. In the excitement he fled to the street with the others and thought the fight was continued outside, he said.

When he returned to sign the typed statement later that night, Banks had his first ever picture taken by a newspaper photographer – in this case, by Ted Miller of the Minneapolis Tribune.

Banks was never implicated in the murder.

Another witness was Fred Snyder, the victim’s brother and fellow union organizer, who named Shetsky as the man who killed his brother after an argument.

Shetsky was indicted on charges of second degree murder by the Hennepin County grand jury on August 1, 1945. He was initially denied bail until his trial, which was set for August 23, 1945. Attorney Archie Cary successfully got him a reversal, and he was let out on bail, which he jumped. It was disclosed in 1952 that four people posted the $20,000 bond:

- Herman Mitch, formerly of Casablanca, Inc.: $5,000

- G. “Mickey” O’Connor: $5,000

- A. Berenson, formerly of Jack’s Restaurant: $5,000

- Tommy Banks: $5,400 (through attorney Cary)

Attorney Cary tried to delay the trial to late September, claiming that he had hay fever at that time of year, but “Judge Carroll disregarded the hay fever plea.” Banks testified at the trial in 1947. Shetsky was first convicted and later acquitted for the shooting.

In 1952, the government said that that the shares were owned as follows:

-

- Banks: 90 shares ($7,800) under the name F.J. Wickers, an employee in his wheel service company.

- Herman Mitch: 34 shares

- Thomas P. Gleason: 56 shares.

Because of the murder, the place was closed from July 21 to August 31, 1945.

On August 3, 1945, William Donnelly deposited $20,000 in cash in the First Produce State bank and received a certified check for the same amount, presumably for the purchase of the Casablanca.

An undated and unsigned memo (probably from the mid 1940s) says that the owner of record was George Benz but suspects that Tommy Banks may have held the deed

When the Casablanca was sold to Toung-Poy (12/1946) and subsequently to A.B. Percansky (9/1948) for $42,500, Banks admitted receiving money.

Minneapolis Daily Times, November 19, 1945

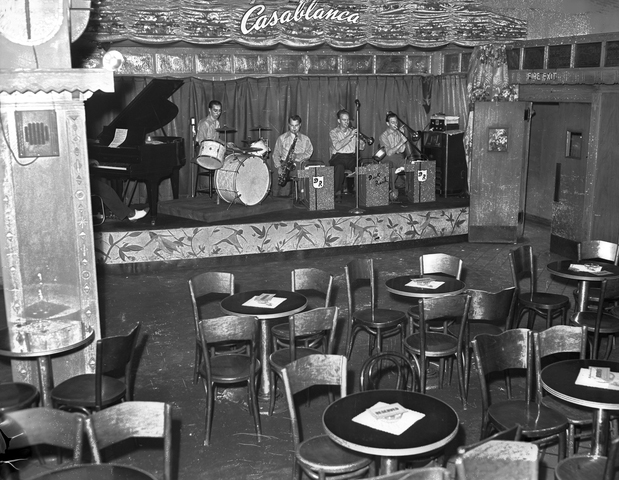

1945 photo of the Dick Rand Band courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Undated ad courtesy Kathy Gillis

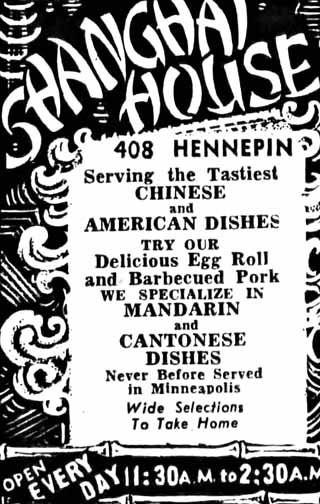

THE SHANGHAI HOUSE

The Shanghai House was advertised at 408 Hennepin from December 1946 to April 1948. It was run by Wang Gin Poy and Wong G. Ping, the same owners of the Paradise, described below. An ad said it was formerly the Casablanca.

Minneapolis Daily Times, April 17, 1947

1948

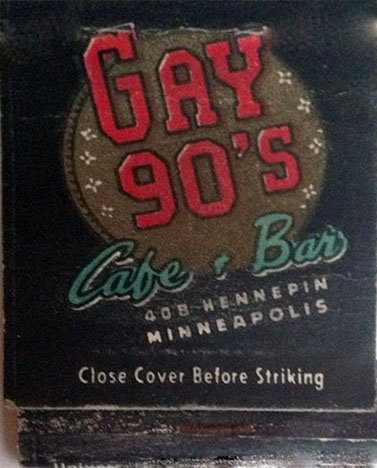

THE GAY ’90s

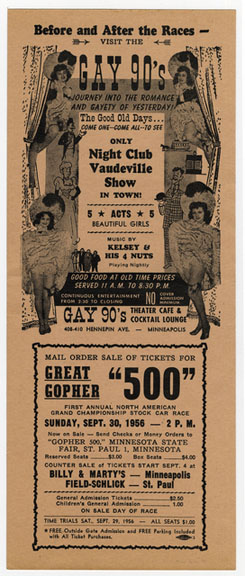

The club was sold to Abe Percansky in about September 1948 for $42,500. The liquor license was in the name of his wife, Mildred Percansky. Local gangster Tommy Banks admitted receiving some money.

It is not to be confused with the Gay Nineties Tavern, on Skid Row.

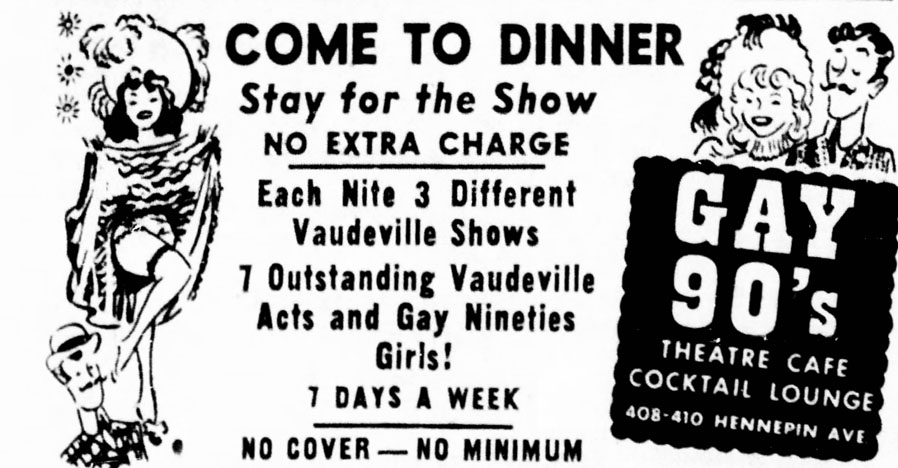

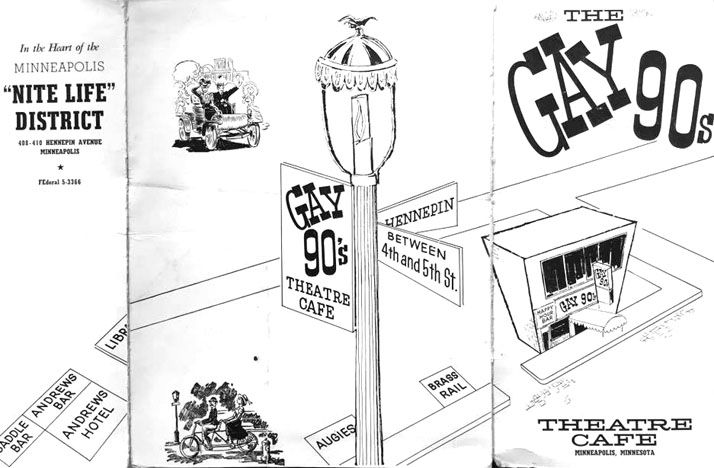

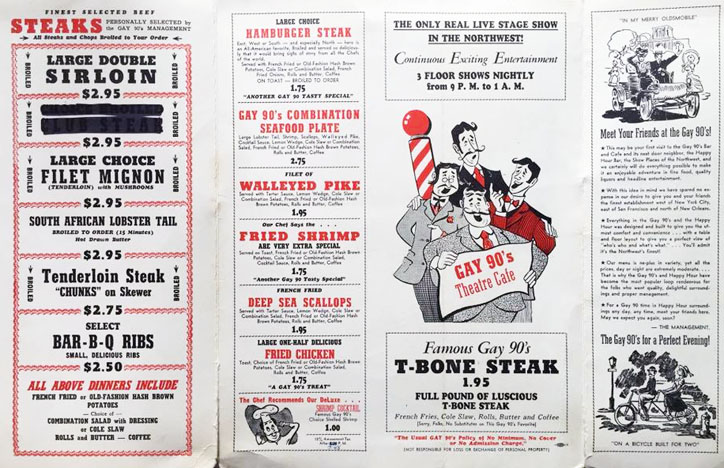

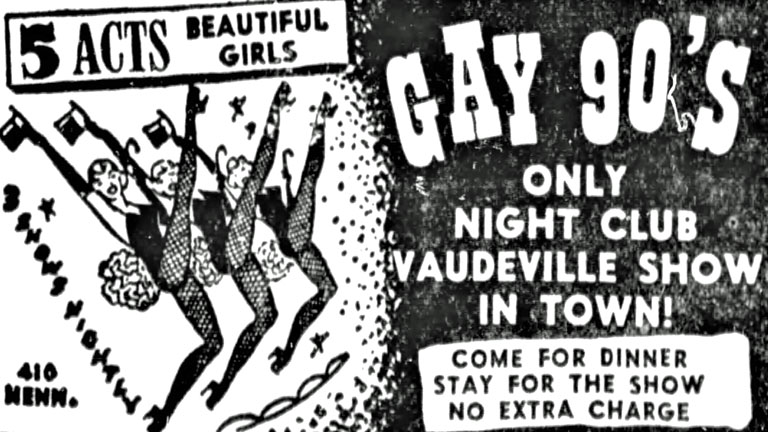

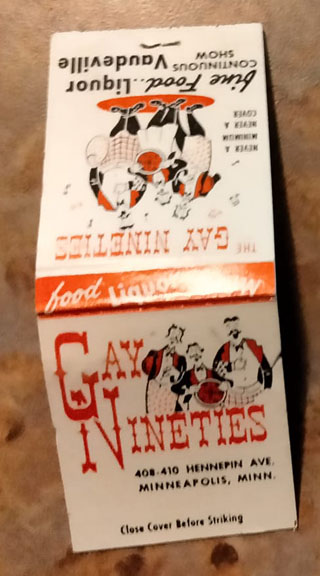

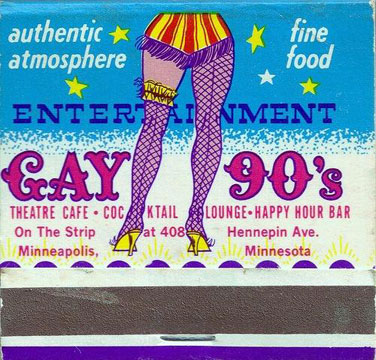

The club opened on October 27, 1948. At first it was called the Gay ’90s Theater Cafe and Cocktail Lounge. A description said it was patterned after the Gay ’90s cafes in New York and San Francisco. There were 19 murals and 35 smaller panels painted with comedy scenes by Bob Sykes and Henry Haderseck.

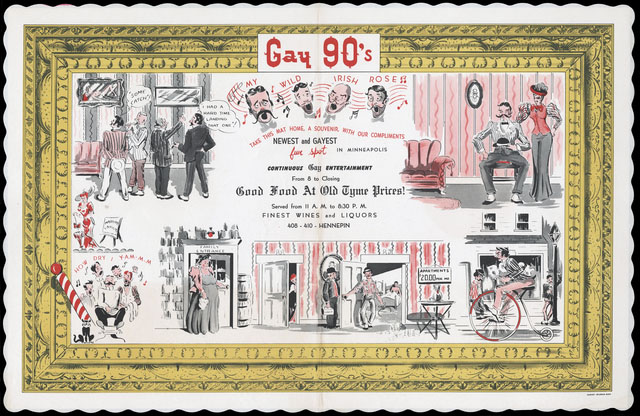

From the collection of Mark Youngblood

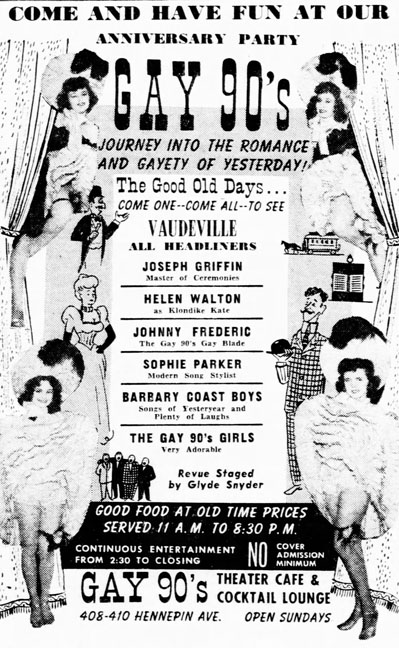

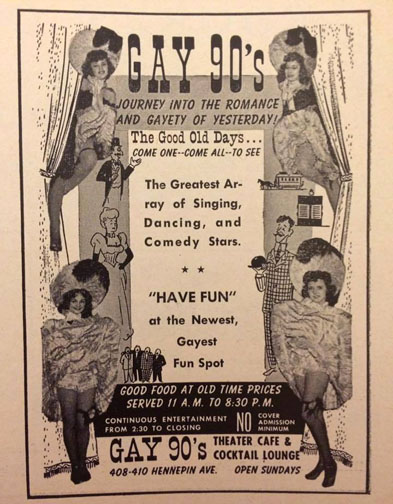

The initial policy was to bring in vaudeville acts, starting with the Gay Blades Trio, singer Sophie Parker, and pianist/singer Corrine Dawn. Lenny Colyer was the M.C. Programs would emphasize turn-of-the-century songs, “now in full flush of a revival.” (Minneapolis Star, October 25, 1948)

Image courtesy Gordon K. Andersen

In November 1948, the club had a show-stopper of a front window: a huge picture frame, inspired by the art gallery frames of the 1890s when gilt and gold were popular. The picture frame front window, which took months of work, started with drawings of frames at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. A plaster cast of a giant frame was made, and then a wax cast was made of the plaster cast. Aluminum was melted over the wax cast, and then five coats of lacquer were painted over the frame. Painting of the frame took 500 man-hours.

Also in November 1948, it was reported that the oyster bar was one of the most popular features of the club, and the chef was studying old cookbooks for dishes that were popular during the turn of the century. (Minneapolis Star, November 29, 1948)

The placemat below calls the Gay ’90s the “newest and gayest fun spot,” so I’ll put this in late 1948/early 1949.

Image courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

1949

Minneapolis Tribune, November 6, 1949

1950

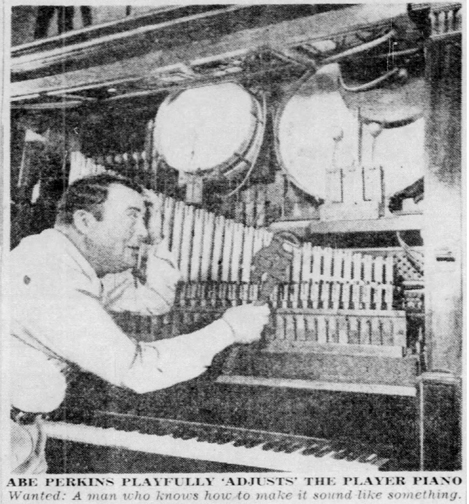

NOT JUST ANY PLAYER PIANO

In 1950, manager A.B. Perkins (a/k/a Abe Percansky) found an old player piano in the place, and a player piano repairman to fix it. It was quite an intricate instrument; it included a xylophone, bass drum, snare drum, cymbal, and organ pipes. It could also be played as a regular piano. The machine also came with 56 music rolls, each having 12 separate songs, such as “If I Should Love You Sweetheart, Ballad,” “Rose Time in Hawaii,” “In a Tent,” “Love Tales,” and “Bow Wow Blues.” Alas, the old piano began to break down again, and Abe lost the name of the repairman. He wanted to put it on the floor of the club, but it was very heavy, with stained glass on the front. On further inspection, it was found to have been made in Chicago and had a slot for nickels. What Abe eventually did with this white elephant, was not reported.

Minneapolis Star, July 18, 1950

The ad below is from a Minnesota Lakers basketball program:

1950 image courtesy Joe Nelson

1951

Minneapolis Star, September 7, 1951

1952

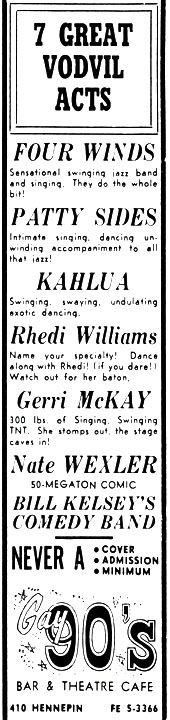

In 1952, the club advertised Eddie Bach and His Jentlemen of Jest – see the Magic Bar for pictures of these knuckleheads. Also five Outstanding Vaudeville Acts, and the Gay Nineties Girls! Three shows nightly – Come to Dinner, Stay for the Show!

There’s no date for the menu below, but the wonderful map on the cover shows that the theater is gone, so it’s after 1953. And the Happy Hour is there, so it must be in or before 1957.

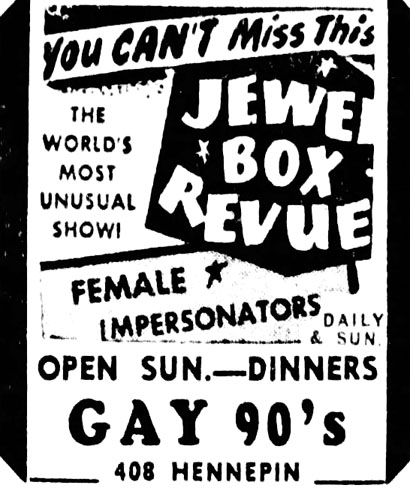

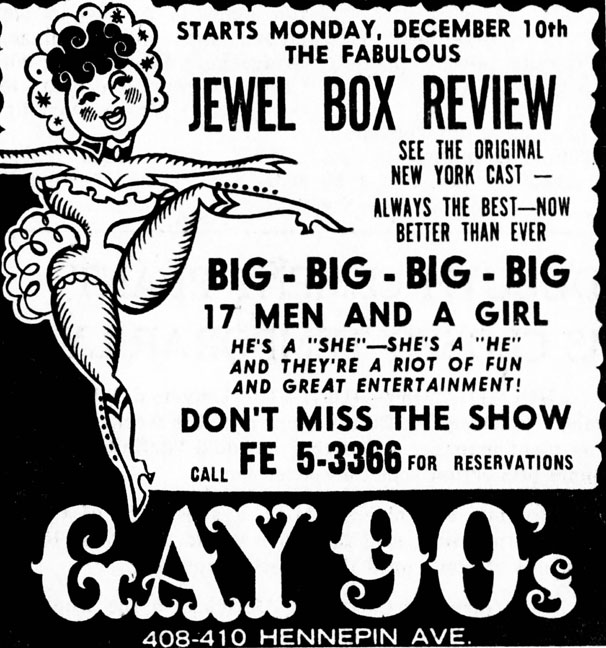

Way back in 1955 there was a traveling show called the Jewel Box Revue. It consisted of men dressed as women, and one woman dressed as a man. In those days the male participants called themselves “female impersonators,” and the Minneapolis Tribune explained that “They dressed in female costumes and affected the mannerisms of women.” The sole woman’s name was Stormy. The troupe had a two-week run at the Gay ’90s, and the Tribune reported that as soon as they were done they promptly left town, as police were ready to file disorderly conduct charges against them. An investigation of the shown was ordered by Municipal Judge Dana Nicholson, who had presided over two female impersonation trials in one week alone. Remember that this was 1955 and there were no gay rights. However, from the ads, the Jewel Box review did return several times to the Gay ’90s.

Minneapolis Star, February 2, 1955

1956

COUNTRY MUSIC

In about 1956, the Gay ’90s experimented in Country music, just as the Flame Cafe was changing its policy to all-Country. Will Jones, entertainment columnist for the Minneapolis Tribune, reported on February 2, 1956, that Dave Dudley’s band was playing there every night, and Texas Bill Strength guested on Tuesday, Friday, and Saturday nights. Billboard concurred that Dave Dudley and His Country Caravan had moved in for an indefinite stand, and that Texas Bill was guesting on Tuesday nights. (Billboard, February 11, 1956)

Photo dated September 30, 1956, courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

1957

Minneapolis Tribune, Monday, December 30, 1957

1958

From 1958 to at least 1962, Night Beat columnist Vic Burton reported that comic Nate Wexler held court at the Gay ’90s, sandwiched in among several other acts, including other comics. (Minneapolis Daily Herald, July 11, 1962)

1959

In 1959, (Mrs.) Abe Percansky sold the Gay ’90s and the Happy Hour to Ben Rackner, Richard G. Gold, and Alan Robert Cohen, the latter also known as “Big Al.” (Ross Cohen)

In his white slavery trial, Abe Percansky testified that his love for prostitute Marilyn Ann Tollefson inspired him to leave the Gay ’90s, where he was floor manager, and go into business for himself at Alice’s Bar, 500 Hennepin Ave. (Minneapolis Tribune, February 21, 1960)

1959 Matchbook – Image courtesy Ross Cohen

1961

Minneapolis Star, December 29, 1961

1962

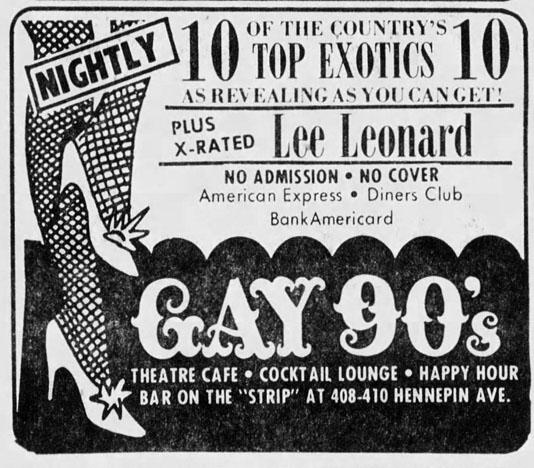

It appears that 1962 may have been a turning point for the Gay ’90s. “Vodvil” seems to have been replaced by exotic dancers like Rikki Corvette, who was 6 ft. 8 inches tall. She had been performing her exotic dance since the late 1950s.

Mpls. Daily Herald, May 23, 1962

In 1962, the musical entertainment was still all over the place. One ad was for a man in a tuxedo named Art Perry, who was the protege of the late Mario Lanza. He was touted as a star who was on his way UP! (Minneapolis Tribune, October 4, 1962)

The ad below indicates that a show made up of “female impersonators” (in the vernacular of the times) made up the entertainment. At that time, being a homosexual was illegal in the State of Minnesota. See the end of this page for a summary (perhaps out of date) on LBGT law.

Minneapolis Star, December 3, 1962

At the end of December 1962, police were cracking down on prostitution in the clubs, and commended co-owner Richard Gold, who held the licenses for the Gay ’90s and the Happy Hour, for being most cooperative. Gold had a policy of asking “suspicious-looking” women to leave, while trying not to be accused of discrimination. During a 14 month period, 14 arrests were made. (Minneapolis Star, December 12, 1962) The investigation was dropped.

1964

6 ‘ 8″ stripper Rikki Covette returned to the Gay ’90s in 1964, performing her show after her performance at the Orpheum Theater in “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.”

1964 photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

1966

Famous 6 ‘ 8″ stripper Rikki Covette returned to the Gay ’90s in 1966, this time to try out her new topless routine before she brought it to Las Vegas. Her memoirs and scrapbooks were eventually donated to the Smithsonian Institution.

1969

1969 Matchbook – Image courtesy Ross Cohen

1970

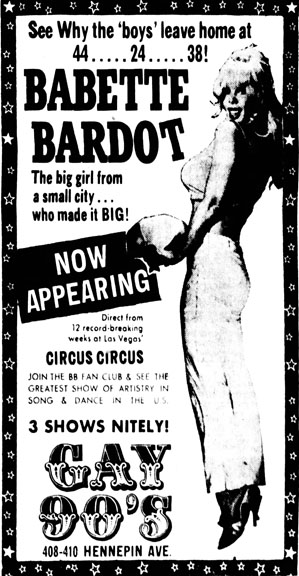

Minneapolis didn’t have a Brigitte Bardot, but we had a Babette Bardot….

Minneapolis Tribune, December 4, 1970

1972

Minneapolis Tribune, March 26, 1972

GOODBYE TO LIVE MUSIC

According to columnist Irv Letovsky, owner Richard Gold dropped the traditional band (in this case the Dave Rooney Trio) for taped music behind the strippers on January 1, 1972. Said Gold:

It works good and everybody’s doing it. You can pick the music you want and the girls can work out their routines the way they want to. Even when we had a three-piece band you couldn’t get much of a sound and you can’t even find three guys who can read music anymore. . . I used to get six or seven girls off the road, but now I’ve got maybe 10 dancers from town and we can train them. They’re younger and cost less and they’re not as hard looking. (Minneapolis Tribune, October 2, 1972)

1975

DISCO DAYS

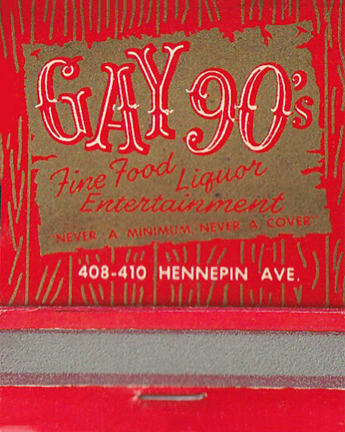

On August 11, 1975, the Minneapolis Star reported that the Gay ’90s would close as a strip-tease bar as of August 23 and open on September 4, 1975, as a disco.

Richard Gold, owner and manager of the Gay Nineties, said the change to recorded rock music will mark the end of 27 years of strippers and live entertainment at the nightclub. ‘The romance of the stripper is gone,” Gold said. The proliferation of pornographic films and adult book stores has diminished interest in live strip-tease performances. The name and the period atmosphere would be preserved, and would not affect the Happy Hour next door, which attracts primarily gay persons. The new Gay Nineties discotheque, Gold predicted, will be a “jazz discotheque” that would attract “the campy crowd that’s on the street today.” (Minneapolis Star, August 11, 1975)

According to discomusic.com (no longer a viable website), a 12 x 12 foot dance floor was installed at the far end of the dining room, and at 10 pm the disco music began playing.

A show bar upstairs featured female impersonators and drag queens.

1977

1977 Matchbook

410 HENNEPIN

410 Hennepin is the Storefront in the Stewart Building furthest away from 4th Street. It has hosted the Happy Hour Bar since the mid 1950s. It is part of a building erected in 1921.

Early business found in that spot may include:

- New Way Radio Co. (1922)

- Henry Clay Shoe Store (1924 – 1934)

- Beauty Parlor

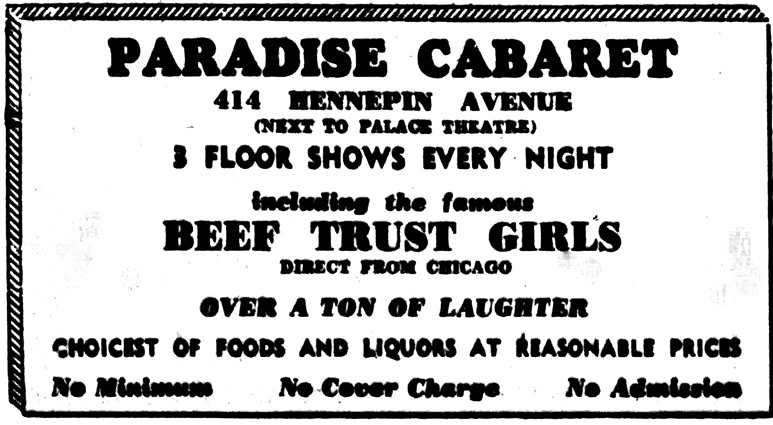

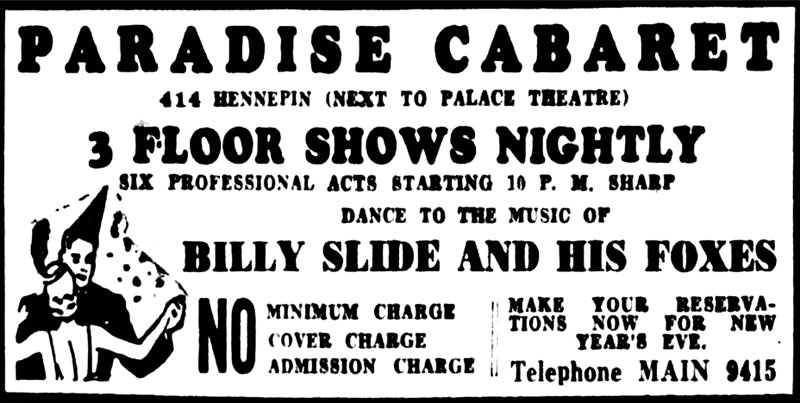

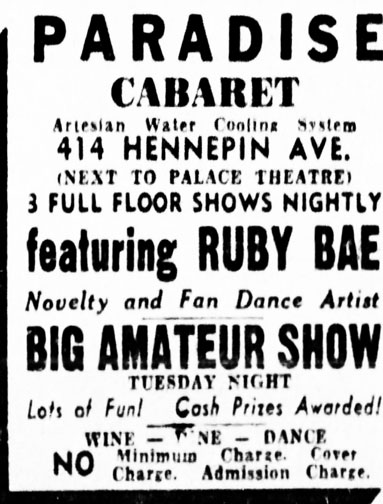

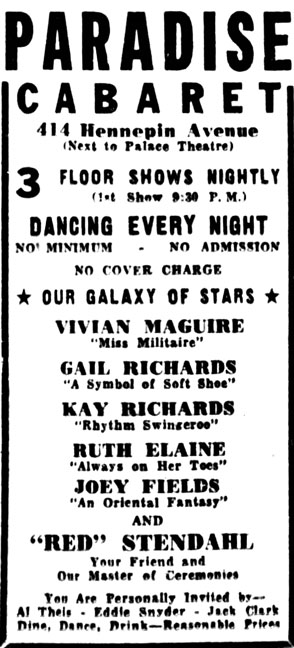

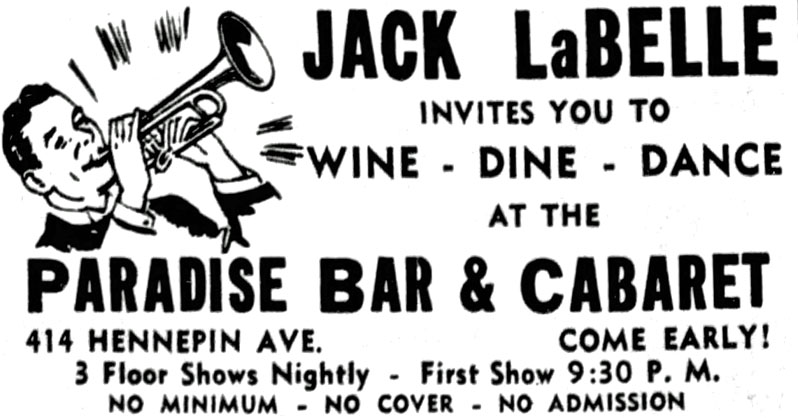

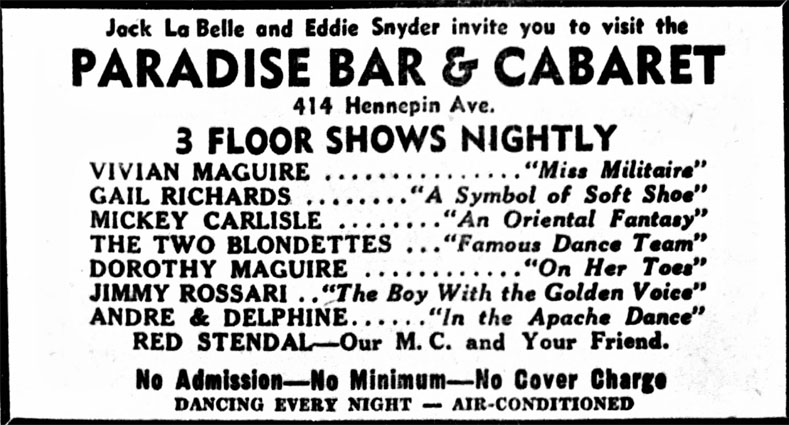

PARADISE CABARET

The Paradise Cabaret was advertised as 414 Hennepin Ave. – “next to Palace Theater.”

The first sighting of the Paradise Cabaret was on August 20, 1936, although there is one indication that the Paradise opened its doors in 1935.

It was a place where jazz musicians would play (and gamble) after hours.

Minneapolis Tribune, September 9, 1936

Minneapolis Tribune, Monday, December 21, 1936

Minneapolis Tribune, Monday, June 21, 1937

In November 1937, the bar was found to be operating without a valid license. The proprietor was Louise Laurentson. As a result, a license was awarded to Al Theis.

Minneapolis Tribune, Wednesday, December 29, 1937

Your host was Red Stendal in 1938:

Minneapolis Tribune, Friday, April 1, 1938

But Jack LaBelle invited us on April 29, 1938:

Minneapolis Tribune, April 29, 1938

And Jack La Belle and Eddie Snyder invited us on June 10, 1938.

Minneapolis Tribune, Friday, June 10, 1938

Red Stendal was back as the M.C. on September 7, 1938.

TROUBLE IN PARADISE

The Paradise Cafe (as it came to be known) met with disaster when it was raided on Sunday, March 12, 1939. Your genial host, Red Stendal, and waitress Helen Dillon were caught serving a highball to a member of the police morals squad at 11:30 pm that Sunday. About 40 patrons were in the place at the time, police said. (Minneapolis Star, March 13, 1939) Al Palmersten, head of the morals squad, said there had been complaints about the place. Red and Helen were arrested and their bail was set at $200 each. (Minneapolis Tribune, March 13, 1939)

The two were arraigned in municipal court on Monday, March 13, 1939, and their trials were set for Friday, March 17. The case was continued until March 29 because Alderman E.A. Hendricks, attorney for the cafe, was on his way to Washington, DC for official business.

On March 30, Red and Helen were convicted of liquor sales violations in municipal court, and sentenced to fines of $100 or 90 days in the workhouse. The sentences were stayed until April 10 to allow time to appeal. Helen was found guilty of selling liquor before the opening hours on March 14, and Red was guilty of selling liquor on Sunday. The judge, Paul Guilford, said,

In these cases, sales were clearly made in an open and notorious way. For this reason I believe licenses of the place should be revoked. (Minneapolis Star, March 30, 1939)

The man who held the licenses for the establishment was Alvin N. Theis, and he and his lawyer fought to keep his licenses despite the actions of his manager and waitress. However, on March 31, 1931, the City Council voted to revoke all licenses attached to the Paradise, and the police came to the club and picked up the licenses. These included his liquor, beer, restaurant, soft drink, cigarette, dance hall and tavern licenses. The Paradise was closed on Friday, March 31, 1939. (Minneapolis Star and Minneapolis Journal, March 31, 1939) On April 8, 1939, Theis was fined $50 for selling liquor after hours.

Coda: Gordon E. Greene, manager of the Palace Theater, applied for a new license for the Paradise Cafe’s spot, but was turned down because there had been 11 convictions growing out of trouble in the Paradise since 1935. (Minneapolis Tribune, April 11, 1939)

The revoked on-sale liquor license for the Paradise Cabaret was transferred to a new location at 401 Plymouth Ave.

The photos below, taken sometime between 1948 and 1953, shows the Paradise taking its place between the Theater and the Gay ’90s.

Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

THE HAPPY HOUR

Don’t confuse this with another Happy Hour on Nicollet Ave., which was built in 1938 – that club burned down in November 1947, and when it was rebuilt it was renamed Club Carnival and then the Famous Flame Cafe.

This club was next to the Gay ’90s and was often referred to as an annex to the larger club. The two clubs operated on the same liquor license. For at least the first ten years, from the mid 1950s, it was owned by Abe Percansky.

The bar became a gay hangout in about 1955, according to one article. (The year 1957 is on the building in tile.)

1962

In 1962 the Happy Hour was owned by Richard G. Gold. He almost lost his licenses over charges of prostitution, but he cooperated with the police in kicking known prostitutes out of the bars (Gay ’90s and the Happy Hour), so the investigation was dropped. (Minneapolis Star, February 20, 1963)

Matchbook image courtesy Gordon K. Andersen

In 1975, owner Richard Gold said “The Happy Hour attracts primarily gay persons.” (Minneapolis Star, August 11, 1975) On September 4, 1975, the Gay ’90s, which Gold also owned, became a disco, and at that time, doorways between the two bars were opened, according to discomusic.com.

1978 Image courtesy Hennepin County Library

414 1/2 HENNEPIN AVE.

414 1/2 Hennepin Ave., I’ve come to realize, must be the address for the basement of the Palace Theater. The businesses may not have given themselves that identification, but that’s my guess.

I’ve made the following list in chronological order, taking hints from the ads themselves when they say “formerly the,” and so on. Please feel free to contact me with better information.

STARKEY

From at least 1915, which is about when the theater was built, the space was used as a deli, lunch counter, or cafe. The name William Starkey predominates until 1924.

SOUTHERN CHICKEN TAVERN

But then out of nowhere, in March 1921, there is an ad for the Southern Chicken Tavern. “Chicken Shacks” were prevalent among saloons that were suddenly put out of business by Prohibition in January 1920, but it’s a mystery as to why this only advertised briefly. It is also labeled 414 1/2, and “next to” the theater.

Minneapolis Tribune, March 20, 1921

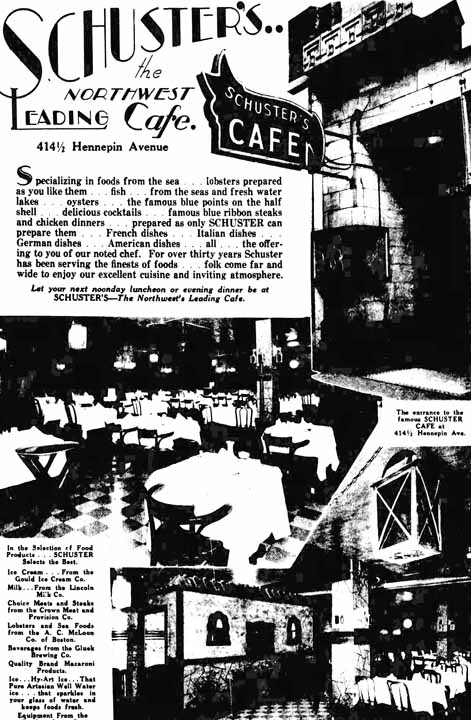

SCHUSTER

In November 1925, we find Schmidt & Schuster joining forces in their downstairs Rathskeller.

After that, it appears to be Schuster’s business from then on. Below is an ad for Schuster’s Cafe in August 1930. Even when the entrance is pointed out, it’s not 100 Percent clear where the restaurant is, but my guess is that that’s the door to the basement.

Minneapolis Tribune, August 30, 1930

OLD HEIDELBERG

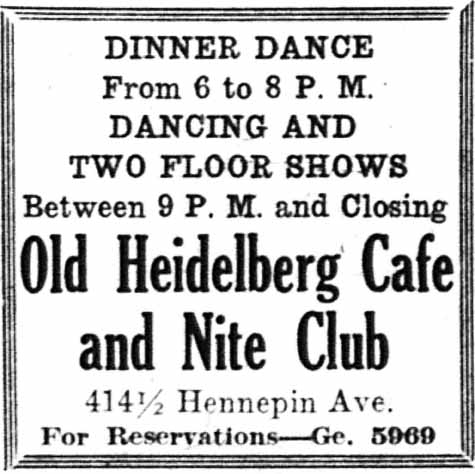

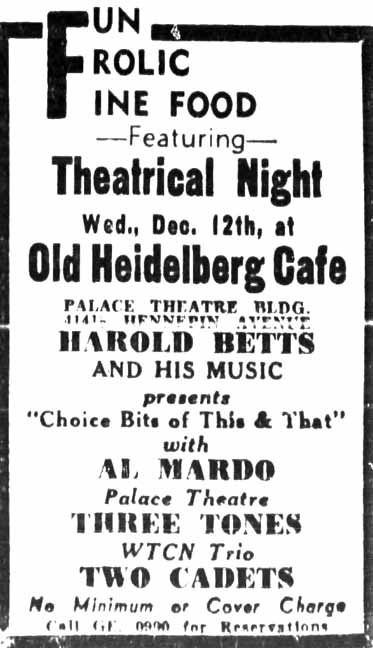

In September 1933, 414 1/2 became the Old Heidelberg Cabaret and Nite Club, heavily advertised in the Saturday Press newspaper. One ad says that it’s in the Palace Theater building.

September 1933

On September 12, 1934, Manager Chuck Foster announced in an ad that the the Old Heidelberg Cabaret (formerly Schuster’s) was opening that day with two big floor shows nightly. A list of vaudeville acts was given, and the house band was Harold Betts and his Rhythm Boys. (Minneapolis Tribune)

The last ad in the major Minneapolis papers for the Old Heidelberg was found in December 1934, below.

Minneapolis Tribune, December 11, 1934

Alas, the Depression likely put this business out of business, not to mention basement dining.

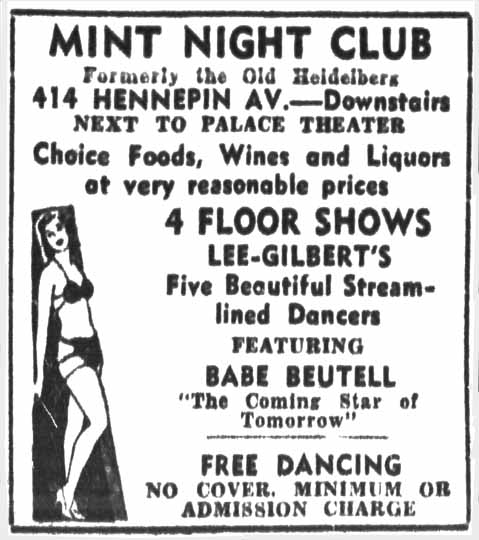

THE MINT

The Mint Night Club was operated by Meyer Gordon, a/k/a Morris, a/k/a Makey to the press, and Mickey on his ads. In one article he was described as a former football player. He had a cat and mouse relationship with the police’s morals squad. This club was definitely described as being “downstairs.”

The club opened on or before January 22, 1935.

Minneapolis Tribune, January 22, 1935

In July 1935, cops from the morals squad made their rounds to the bars at the 2 am closing time, and Detective Walter Hansford, head of the squad, noticed that there was a considerable crowd still inside the Mint. He demanded admittance, but the proprietor told him that the doors was locked and gosh darn! the key was missing. Hansford sent for a crowbar, and wouldn’t you know, they found the key and no liquor was to be found! (Minneapolis Tribune, July 20, 1935)

But the next night, early Sunday morning, another raid resulted in the arrest of Makey Gordon, who was selling liquor after hours. Police noted that the place was packed at 1:15 when they made their move. Makey plead not guilty and the trial was set for July 24. He and another scofflaw from another bar were each fined $50.

Minneapolis Tribune, August 17, 1935

Later that year, things really heated up at the Mint. The account in the Minneapolis Star says that representatives of the Minneapolis Retail Liquor Dealers’ Association came into the bar to sell tickets to a banquet planned by the liquor dealers at the Club Lido. Apparently they were not welcome, because the pair were beat up by employees.

Then, two police officers came to make sure that the bar closed at closing time. They testified that they were “set upon and beaten.”

Up to that time, there had been arrests at the Mint for violations of the liquor laws: one conviction, one acquittal, and one charge was dismissed. (Minneapolis Star, October 9, 1935)

As a result of this violence, Morris (“Izzie”) Garber, one of the proprietors, was locked up and charged with assault and battery. This charge was dismissed.

Also arrested were doorman Thomas Lunde.

Bartender Robert Hill was charged with selling liquor without a license, plead not guilty, and posted $100 bail. (Minneapolis Star, October 10, 1935)

If that weren’t enough trouble, on December 12, waitress Myra Thompson was arrested for selling liquor after hours. She pleaded guilty and was fined $10. (Minneapolis Star, December 13, 1935.)

That was it. On December 28, 1935, Mayor Thomas E. Latimer revoked all licenses for the Mint, following three convictions. The Grand Jury wanted to know why the place was still open despite the fact that Macey Gordon had transferred his liquor license to Patrick J. Monahan, one of his bartenders, on December 13, 1935, to take effect on January 1, 1936. (Minneapolis Star, December 28, 1935)

On January 1, 1936, the Mint opened again “under new management.”

Ah, but trickery doesn’t bode well by the police. On January 4, 1936, the Chief of Police came to shut it down, but the vampire of clubs wouldn’t die until January 6, 1936, when the Grand Jury ordered the place shut for good. Patrolman Joseph E. Kolars and Thomas P. Flaherty received the order from Captain George Hillstrom to put a stake through its heart.

ENLISTED VETERANS OF AMERICA POST 11

At this point the owners of the building (at one point named as George Benz’s Sons) began renting out the space, perhaps beginning in May 1946. One group that rented it often was the Enlisted Veterans of America, Post 11.

Minneapolis Star, Friday, June 21, 1946

The organization had been put together by a man who went by the name of Al Firotto, born Alexander Fecarotta, a/k/a Ray Farrell. He had been a hero in the War, but had a shady reputation in Minneapolis. The police had unsuccessfully raided the place several times, but on February 10, 1947, a police woman came in and said she was waiting for her boyfriend – a busboy – to get off of work. She was able to buy a drink, although Firoito had no liquor license, and she signaled the morals squad to raid the place. They found 42 bottles of booze.

Fiorotto was arraigned on February 11, 1947, and scheduled for trial on the 14th. His defense was that he had no official connection with the club. He was convicted anyway, and sentenced to 90 days in the workhouse, but since the manager was actually his brother Robert, the judge gave him the benefit of the doubt and stayed his sentence. The club didn’t last much longer, though.

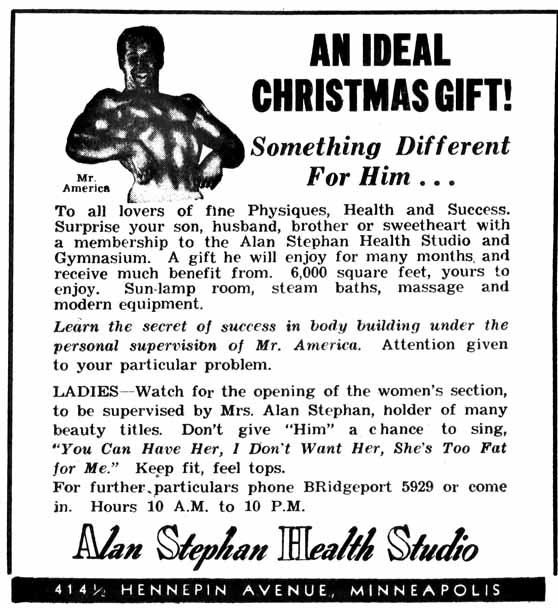

ALAN STEPHAN HEALTH STUDIO

An article dated May 17, 1947, states that body builder Alan Stephan (“Mr. America”) had opened a health studio at 414 1/2 Hennepin Ave. This was in the basement of the Theater, as it appears in the photo below.

Photo taken on May 25, 1953 courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Stephan met his fiance, Grace Pomazal (“Miss Legionaire”), at a personal appearance in Chicago, and they decided to settle down in Minneapolis. (Minneapolis Star, May 28, 1947) The couple married on June 16, 1947, at the Basilica of St. Mary, and after the honeymoon up north, the bride, also known as “Miss Quick Freeze” and “Miss Forget Me Knot,” planned to work as her husband’s receptionist at the health studio.

Alan, who was named “Mr. America” in a contest in New York sponsored by the International Federation of Body Builders in November 1948, met Miss America BeBe Shoppe a month later, and proceeded to hoist her on his shoulder for the cameras. (Minneapolis Tribune, December 29, 1948).

Stephan was at this address in 1953, but by 1955 he had moved to 704 Hennepin. (The theater was demolished in 1953.)

Minneapolis Times Picture Paper, November 20, 1947

A search to find out whatever happened to Alan finds him at three locations in 1958, under the name American Health Studios, a chain. (Minneapolis Tribune, February 24, 1958) And in a 1973 article in the Tribune about health club chains, he complained that a gym chain from Houston used unfair methods to run him out of business, and then the chain itself went out of business. (December 30, 1973)