Professor James Frances Patrick O’Neill

FROM DON BETZOLD

The following tribute to one of the classic KDWB Disc Jockeys was written by former State Senator and avid KDWB fan Don Betzold. It is reproduced here with the permission of Senator Betzold and courtesy of the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting.

In the 1960s, every Twin Cities teenager knew there were two, and only two, Top 40 radio stations. At one end of the AM radio dial at 1130 was WDGY. “Wee-Gee” was the heavyweight with the powerful signal which could be heard all over the Midwest. At the opposite end of the AM dial at 630 was KDWB, Channel 63, which could hardly be heard 25 miles out of town. The two stations played the same Top 40 records, which was quite a variety back then, including rock ‘n roll, ballads, country western, folk, a little jazz or rhythm and blues, Motown, instrumentals, and even novelty songs. Their contests and promotional giveaways were modest. A lucky listener might win a new 45 single.

Despite their format similarities, there was a world of difference between the WDGY and KDWB. To me, the WDGY announcers sounded pretty much the same. It also seemed to me that they spun the vinyl singles on their turntables just a little bit faster than 45 revolutions per minute so that they could play more records per hour.

I was loyal to KDWB from the time that I bought my first transistor radio from my father’s appliance store in July 1961 and soon thereafter happened upon its 63 “easy to remember” frequency. I thought the disk jockeys were clever and happy to be there. They were billed as “the Seven Swinging Gentlemen.” Each had his own style for his own program, from Hal Murray’s zany jokes in the morning, followed by Art Way and Bob Friend, to our “lovable leader” Lou Riegert in the evening, followed by Randy Cook and then Don Duchene at midnight.

James Francis Patrick O’Neill, the afternoon host, was the best of them. He joined the station about the time I started listening, and I listened to him every chance I had for six years.

As a disk jockey on a Top 40 station, his job was to play the latest hits. O’Neill didn’t just announce the next record and move on; when the song was over, he would find a nice quip or a pun to tie into it. He might even offer a personal view on a Top 40 record. I once heard him play “In Dreams,” then a current hit by Roy Orbison. When the song was over, O’Neill said that he really didn’t care much for the song when he first heard it, but it grew on him.

What distinguished O’Neill from other announcers was how he used his airtime. He put on a real show. Initially he was on three hours a day, later four hours every day, six days a week, 50 weeks a year, taking two weeks of vacation in July.

JFPO called himself “Professor” O’Neill. He carried that schtick to the publicity photos in the weekly Top 40 record surveys. Instead of posing with the traditional head shot, he wore a mortarboard and tassel with a graduation robe, sporting glasses and a raised index finger pressed against his creek, his other fingers curled and resting under his chin. The photo didn’t give his audience a clue what he really looked like; we had to use our imaginations.

He spent hours each day preparing for his daily show. He claimed to have “a cast of thousands” and he referred to his “studio audience” to the point where one almost believed there was such a thing. He conversed with his many voice effects and made us laugh with his dry sense of good humor. His radio characters included Snooky Lanson and poet laureate Keates Schmidlap, who gave thoughtful advice in his ditty, ending in a pun. He made parodies of his own station; D.J. Leary had the “Live Line to the World of Sports”, O’Neill created “D. J. Looney” in rebuttal. O’Neill could work up a joke based on Will Rogers or Louisa May Alcott. He included forgotten historical events, like the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, into his off-beat dialogue. He did skits based on local news, so you had to pay attention to current events to get the gist of his satire. He even prefaced normally mundane announcements of the time and temperature with a quip, for example, “K-D-W-B ‘whatever-happened-to-Hailey-Mills?’ time is 5:17.” He might imagine some “schlep” who had “a smile on his lips, and song in his heart, and two tickets to the midnight showing of Rebecca at Sunnybrook Farm.” He used big, sophisticated words, like “aficionados,” “inveterate,” or “halitosis,” causing this teenager to go to the dictionary so I could understand his jokes.

He had continuing humorous sagas, which often ran each day for weeks. He had a passionate campaign to stop Lake Phalen from leaking. Each summer, he gave reports from his mythical Camp Nitty-Get-Get, with his own theme song which included the line “I hope the check my daddy writes don’t bounce back to you.” During the elections of 1964, he used his airtime to campaign for Mayor of Dinkeytown. I was a high school freshman that autumn and I mailed in my written ideas, which he read on the air with kudos to me.

He was never mean or insulting, just funny. Unlike other deejays, he offered occasional glimpses into his own well traveled life, invariably as part of some joke. He mentioned his stint in the Army. Sometimes he told us a little about his family, always with affection. One late August, he teasingly described how unhappy his daughter was because summer vacation was almost over and she had to go back to school, a sentiment I shared.

He ended each show with “Recipes I’ve gotten sick to.” My favorite was pickled herring upside-down cake. After he read the recipe, he groaned with a “yeech,” as though someone else had sent the concoction to him. As the instrumental played in the background and the clock headed to the newscast at the top of the hour, O’Neill would proclaim that “the last four hours have been a veritable ball.” (How many times do you hear the word “veritable”?) He’d then promise “we’ll do it again tomorrow.” He would then caution us: “Don’t take any nickel nickels, hey.” And finally he would end his program with his signature phrase, “See you out there!”

It was a fun time to listen to Top 40 radio.

Then times changed, starting with the assassination of President Kennedy. When the Beatles led the British music invasion two months later, the music got much better, and the radio stations which played the records changed as well. “Much more music” meant less jock talk. More rock also meant no more of any other kind of music. With few exceptions, if it wasn’t rock, it wasn’t played. Any record released prior to 1964 was scratched from the playlist. Soon, newscasts were gone. The newer, younger deejays had one main job: announce the next record and keep playing the hits. There was no time to entertain, to ponder, to offer ideas, to establish an identity with the audience.

The days of the personality deejay were over. I wrote my protest letter to the program director at KDWB. He responded with a very polite note explaining that this was the direction of the radio industry. I kept listening to Jim O’Neill’s daily program. He still managed to work in a few funny lines and an occasional bit, but he was being crowded out with too little airtime to work his craft. He had to spend more time announcing the next record and playing more non stop hits. Undoubtedly, the changing times also made it tough for O’Neill. It must have been hard to put together a glib, light-hearted show when our attention was on the Vietnam War and riots at Selby-Dale in Saint Paul and Plymouth Avenue in Minneapolis.

Jim O’Neill signed off at KDWB for the last time on Friday morning, August 25, 1967. By then, his program had been moved to the 6 a.m. to 10 a.m. slot. Shortly before 10 a.m., he said that “the last six years have been a veritable ball.” There was no promise that we would do it again tomorrow. After he said “See you out there!” he played his final record, “Jackson” by Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazelwood, and was gone from our local airwaves. Then the next deejay started his shift, and the hits just kept on coming.

I never met Jim O’Neill. I saw him from afar at the 1965 Beatles concert at Metropolitan Stadium when he was introduced with other deejays from KDWB and WDGY, just before the Beatles took the makeshift stage.

I finally had the chance to visit the KDWB studio in October 1967, less than two months after Jim O’Neill left. As I looked around that small building, I saw no visible evidence that he had ever been there. The studio where the on-air deejay sat was a modest soundproof room, with the turntables, microphone, tape cartridges, and audio board, all contained in a small space. The record library, with a hundred hours or so of past hits, was in the back of the room. It was just an old wooden bookcase, about three feet high, each shelf crammed end-to-end with 45’s.

On that visit, I met a part-time deejay, and asked him about Jim O’Neill. The announcer mentioned, with some awe, that O’Neill was in his forties. Actually, JFPO was in his late thirties at the time, but the point was still the same. It was remarkable that someone so “old” was doing this kind of work. Then the deejay said with a certain amount of amazement, “he was incredible. He’d get up at three in the morning and start writing his show!”

A few weeks later, I had to write the caption which I wanted published about me in my 1968 senior yearbook. As a tribute to Jim O’Neill, I wrote that my favorite saying was: “See you out there” and that is what was printed under my senior photo. I adopted his signature phrase then, and I continue to use it to this day.

As a teenager, I was bound and determined to become a disk jockey, just like Jim O’Neill. But I never had his talent; few people do.

Many things have changed around here since Jim O’Neill left town. The old KDWB studio building which sat in a desolate field near Lake Elmo on Highway 12 and Radio Drive is long gone. A large empty office building now sits on its ground. The surrounding radio towers are long gone as well. Highway 12 has become Interstate 394. Radio Drive was once a little dirt road leading from the highway to the station; now it’s a major road through the booming suburb of Woodbury. I doubt that any of the thousands of people who drive on it know why it was named “Radio Drive.” The 630 AM frequency now belongs to a Spanish-speaking radio station. KDWB became an FM station in the mid-1970s with a powerful signal, and moved its studios to Richfield. They still play today’s popular music, but they can’t play any of the music which built the station because their young audience wouldn’t listen to it.

In September 1967, Jim O’Neill started his new radio job as the “Morning Mayor” at WLW-AM in Cincinnati. His task was to unseat the morning ratings king at a rival station. He did it. O’Neill’s humorous program became the number one morning radio show in that market. He stayed at WLW for the next 15 years and then worked at another Cincinnati station after that.

Jim O’Neill died on June 24, 2004 at the age of 75. His Cincinnati Enquirer obituary said that O’Neill’s colleagues called him “the lovable one.” One Cincinnati announcer remembered that “he was the most prepared guy I ever worked with. He always had a stack of material. He was a radio man. He lived radio.”

I learned to appreciate his dry, witty humor. I’m happy to remember a man I never met, but with whom I regularly shared a little time every day during six teenaged years of my youth. I was glad to be one of the Professor’s “students.” It was a veritable ball.

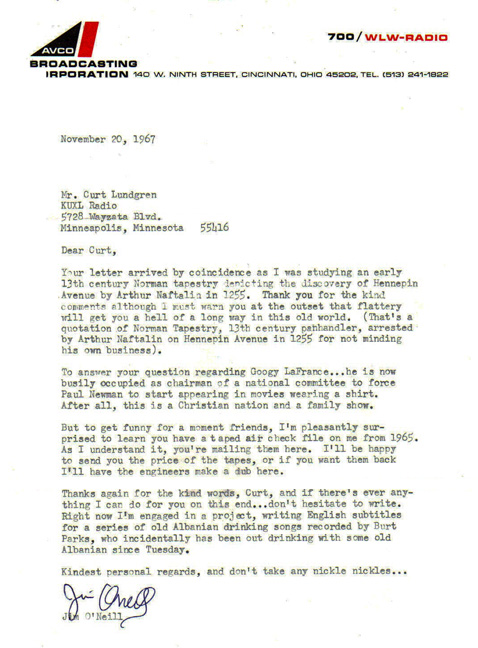

FROM CURT LUNDGREN

In 1967, Curt Lundgren, a future disk jockey himself, was also a big fan of Jim O’Neill, and was happy when the Professor took the time and thought to give him a humorous response to his fan letter. 55 years later, Curt shared it with me, and now you: