Since my website has to do with live entertainment, and that often happens where they sell alcohol, I thought I would attempt a page that had to do with Liquor. That is,

I. Prohibition and Other Liquor Laws

II. Drinking Age Changes in Minnesota

III. Liquor Limits in Minneapolis and St. Paul

IV. B-Girls: A Lesson in Trickery

V. Lid Tipping

For each of these I will start a new chronology, so as not to get cornfused, pardon the bad pun.

I. PROHIBITION AND OTHER LIQUOR LAWS

I will won’t try to explain everything about the very complicated topic of Prohibition, but will go through some basic milestones and some peculiarities in the Twin Cities.

This information comes from a piece I wrote for the St. Louis Park Historical Society, so it is heavy with Park information. Books consulted on the subject were Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, by Daniel Okrent (2010); and Prohibition: Thirteen Years That Changed America, by Edward Behr (1996). The former was affiliated with the Ken Burns documentary, and the latter was a companion to an A&E special presentation.

The first saloon in Minnesota was established in the 1830s by Pig’s Eye Parrant in a cave in St. Paul.

The first temperance society sprung up in 1848.

Minnesota had an early prohibition law in 1852, but the abolitionist movement moved to center stage and the law was repealed.

Liquor taxes were essential to pay for the cost of the Civil War.

1883

The Prohibition Party of Hennepin County had its convention on September 26, 1883, convened by chairman J.B. Stevens. The Resolutions are worth repeating, as reported by the Minneapolis Tribune:

- The prohibitionists of Hennepin county in convention assembled do hereby declare their allegiance to the Prohibition Home Protection party of this state and nation, and hereby pledge this party our hearty support.

- We are as ever fully convinced that nothing short of the entire prohibition of the liquor traffic as a beverage will remedy the great evils of intemperance, and we therefore again declare ourselves opposed to any license regulation, knowing it to be an utter failure in suppressing these evils.

- That high license as a policy in relation to this traffic has proven itself a delusion and a snare and has nothing whatever in it to benefit the cause of temperance or the interest of the country at large; and we do hereby discard it as one of the false compromises which the enemy is over throwing in the way of prohibition and national progress.

- Believing that prohibition as a political principle demands the efficient aid of a political party, we do, therefore, by our meeting together today and the nomination of a ticket, place ourselves right before the people on this question.

1890

The Hennepin County Prohibition Party had its convention at the Labor Temple on June 13, 1890. They elected a new county committee and appointed delegates to the state Prohibition Convention which convened on June 24. George F. Whitcomb was elected president. Most of the delegates were from Minneapolis.

1891

A cautionary tale was the story of Louis Retwat, a Norwegian laborer who was killed by a Hastings and Dakota freight train near Lake Calhoun in April 1891. Although the engineer did everything to warn him and stop the train, Retwat made no movement until the train was within a few feet away. He had been working in St. Louis Park grading but he quit and took to drinking; “A bottle containing a few drops of alcohol explained his seeming indifference to the approach of the train…”

1893

The (National) Anti-Saloon League was established in 1893. Its prime legal advisor and lobbyist Wayne Wheeler would become the prime architect of Prohibition.

During these years before national Prohibition, the individual municipalities voted each year whether to be wet or dry. During dry years, there were still plenty of places to get a drink. Some were called Blind Pigs, and some were Speakeasies.

Wikipedia on the concept of the Blind Pig:

The term “blind pig” (or “blind tiger”) originated in the United States in the 19th century; it was applied to lower-class establishments that sold alcoholic beverages illegally. The operator of an establishment (such as a saloon or bar) would charge customers to see an attraction (such as an animal) and then serve a “complimentary” alcoholic beverage, thus circumventing the law.

A speakeasy was usually a higher-class establishment that offered food and entertainment. In large cities, some speakeasies even required a coat and tie for men, and evening dress for women. A blind pig was usually a dive where only beer and liquor were offered.

Another explanation of the term “Blind Pig” is that the police were bribed into looking the other way, making for a “blind pig.”

1899

In 1899 lunatic Carry Nation carried out her first hatchet job in a Medicine Lodge, Kansas, drug store that was illegally selling liquor. After several raids in Kansas, she branched out to other cities, including New York. She became a media sensation – songs were written about her and her name is known to this day. She died in a mental institution at age 65.

1912

During the 1912 liquor election in St. Louis Park, the wets argued that if the village went dry, everyone would go to Minneapolis to drink and it would cause havoc on the street cars. Although street railway officials were sure that they could control the situation, the wets won anyway.

1917 – 1918

State beer drinking (and revenue) fell 35 percent between April 1917 and April 1918, according to a May 5, 1918 article in the Minneapolis Tribune. Beer consumption in Minnesota fell from 112,918 barrels to 72,644. This may have been due to a temporary World War I limit of 2.75 percent alcohol percentage in beer.

The 42nd Annual convention of the Minnesota WCTU met in Duluth on September 17 – 20, 1918. Topics under discussion, as reported by the Minneapolis Morning Tribune, would be women in war industry, war activities of the WCTU, moral education as applied to army camps, Americanization, and food conservation and war gardens. The WCTU would continue their works after prohibition was enacted. A 1922 article found them giving a benefit musical show to raise funds for a “mother-child” center for foreign speaking women in the city. The group provided a sermon and flowers to 921 prisoners at Stillwater.

The Minneapolis Daily News of November 11, 1918, reported that, upon the advice of the City Health Commissioner, the Minneapolis Chief of Police ordered all Minneapolis saloons and cafes closed for the day. They will remain closed until after the voluntary peace celebration undertaken by the people upon receipt of news the armistice between the allies and Germany has been signed. This was primarily because the city was still subject to the Spanish Flu epidemic, and all places where crowds might gather, such as soda fountains, would also be closed.

THE PROHIBITION AMENDMENT

The 18th Amendment to the Constitution, was passed by Congress on December 18, 1917.

Section 1 reads:

After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

It was ratified by three fourths of the State Legislatures on January 16, 1919 by Nebraska, the 36th of the 48 states then in the Union to ratify the amendment. Minnesota was the 39th state to ratify it, on January 17, 1919. Only two states, Rhode Island and Connecticut, rejected the amendment.

THE VOLSTEAD ACT

Congress passed the 12,000 word Volstead Act (actually the National Prohibition Act), which was the enforcement legislation, in October 1919 over the veto of President Wilson. The Volstead Act spelled out the specific prohibitions, definitions, exceptions, and penalties.

Andrew John Volstead, a 10-term Republican Congressman from Granite Falls, Minnesota, and chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, was more a facilitator of the law than the author – the architect was really Wayne Wheeler of the Anti-Saloon League. Nevertheless, Volstead was a firm believer; the conclusion of an undated speech demonstrates his fervor:

I am proud that America is leading in this great movement. The eyes of the world are upon us, and from innumerable homes, here and beyond the seas, prayers go up for the success of the cause. Are we going to disappoint them? No! A thousand times no! the men and women who wrote the prohibition amendment into the National Constitution will, I am sure, sustain it. A nation that was brave enough and generous enough to give millions of its men and billions of its money in the World War will turn aside with contempt from the sneers and taunts of those who selfishly and petulantly insist that their right to indulge in intoxicating drinks is superior to all law and more important than the public good.

The nation went dry overnight on January 16, 1920. Selling alcohol – beverages containing more than one-half of one percent alcohol – became a Federal crime, although the 18th Amendment stipulated that “The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” States passed their own prohibition laws, as apparently did cities and villages.

There were several exceptions outlined in the Volstead Act, including sacramental wine (leading to many a phony priest and rabbi), homemade cider, industrial alcohol, alcohol prescribed by a doctor (no more than a pint every ten days), flavoring extracts, syrups, and vinegar. You could make “near beer” with less than .5 percent alcohol but you couldn’t call it beer.

You could also drink all the alcohol you wanted, as long as you had purchased it before January 17, 1920. Many people stockpiled the stuff, and bottles are still being found squirreled away in attics today.

As for Volstead, he lost his re-election campaign in 1922 and died in 1947. A portrait of him made of beer bottle caps can be seen in the Volstead Lounge at the Freehouse Brew Pub, 701 N. Washington Ave. in Minneapolis.

WHY PROHIBITION?

Prohibition came about for several reasons, and several books have been written about it. One impetus was the proliferation of saloons where men could go to get away from their families and potentially spend the rent money. Women won the right to vote in 1920 and were becoming more and more influential in public opinion, and they wanted their men out of the saloons.

Second, there was the German factor. The U.S. entered into World War I on April 6, 1917, and the country railed against anything German, which included beer. What didn’t help is that the brewers were overwhelmingly German and didn’t repudiate the actions of Germany sufficiently.

Another reason was racism; southerners wanted to keep alcohol away from blacks for fear they would get drunk and commit crimes against whites. The Ku Klux Klan participated in this line of thought, although arguably they hated Catholics just as much as whites, and Catholics were notably “wet.”

Yet another factor was financial. The Sixteenth Amendment was passed in 1913, allowing the Federal Government to collect income tax for the first time. This meant that money lost from taxing liquor could be made up for with income taxes. Needless to say, the big capitalists of the time did not appreciate this incursion into their fabulous incomes, and their opposition to prohibition was a major factor in getting it repealed. Unfortunately, the return of liquor taxes did not make income taxes go away as they had hoped.

And not to be forgotten was the skill and tenacity of Wayne Wheeler of the Anti-Saloon League, who was able to influence elections in tight races.

BOOTLEGGING

Bootleggers flourished during Prohibition, and locally the biggest was Isadore “Kid Cann” Blumenfeld (1900-1981), who led the “Minneapolis Combination.” This benevolent group apparently not only supplied hooch locally, but ran it down to Iowa as well.

In Minneapolis the speakeasies were concentrated in the Gateway District, which was known for its wall-to-wall bars, liquor stores, and flop houses. They lasted until well into the 1950s, when Urban Renewal came along and leveled the area, displacing up to 3,000 “skid row bums,” many of them WWII Veterans.

Unregulated by the Government, the quality of the liquor was unpredictable and often dangerous. Ben Brown remembers that “there was much public drunkenness, and drinkers spiked their drinks far too heavily and became drunk in short order. It was very common to see men staggering down the street and sometimes fall and lay on the road or sidewalk. A pitiful sight to witness.”

Ben also remembers when “one bootlegger just down the block from his father’s Barber Shop and Pool Hall was raided several times by the Feds, but they never found anything. Turns out there was a rubber hose in the drain plug in the bathtub that led to a secret storage area underneath.” A local plumber may have been involved with such riggings…

It just may be that the local plumber was Tom Motzko. His son Frank tells the story about how his father did the plumbing for the Glen Lake Sanitarium, but made more money selling moonshine than the plumbing. Everything the family had was first class!

Mike Jennings, later of Jennings Tavern and Liquor Store, was said to be active in his line of work before 1933. One day it was reported that the Feds raided a house that Mike had rented for $75 a month, in a day when rents were typically $16. The raid yielded dozens of 5-gallon cans, which the Feds punctured with axes and poured out on the ground in the vacant lot next to the house.

Another story about Mike is that he was in cahoots with a depot agent in North Dakota. Liquor was shipped from Canada to a fictitious name in this North Dakota town. The depot agent would then auction off the “unclaimed” freight and Mike was always the buyer. Then drivers would deliver it to the Twin Cities.

It turned out that Minnesota, home of Congressman Volstead, was particularly conducive to bootlegging, having a long border with Canada, and the nearby North Dakota border was easily crossed on old farm roads. My Canadian Uncle Alf says that Studebaker made a special car to accommodate the rumrunners. It was made with an extra heavy frame, had heavy-duty wheels and tires, was extra long, and had the most powerful engine made in the U.S. It was marketed as a seven passenger family car, with two folding seats installed in the very large floor space between the front and back seats. This car could transport a ton of hooch at high speed.

1925

To try to attack the problem of bootlegging, Congress passed the Jones Act in 1925, which greatly increased the amounts of fines and jail time for violators of the Volstead Act. But that was Federal law, at a time when states were repealing their own prohibition laws as unenforceable.

1927

Bootleggers in Edina; Sheriff Seizes Plant (Hennepin County Enterprise, September 1, 1927)

Sheriff Earle Brown and his deputies seized a plant of contraband whiskey in the peaceful village of Edna. The plant and contents is valued at $10,000. One man is being held by the sheriff for examination.

The place where it was found was a spacious residence, of old time architecture, and according to Sheriff Brown, the plant was the most completely equipped establishment for its purpose, ever unearthed in Hennepin County.

It is supposed that the bootleggers had been there only a short time and that the location was selected for its obscure surroundings and was intended as a base of supplies for the dealers of Minneapolis.

The bootleggers made the mistake of not keeping their warehouse in Minneapolis. It is extremely dangerous for them in Sheriff Brown’s domain.

The nefarious Edina bootlegger was subsequently identified as Roy Stanchfield, who was arraigned before Judge Ray W. Meeker of Richfield on a charge of maintaining a nuisance, and was sentenced to 60 days in the workhouse. “It is supposed that the prisoner had connections with a notorious gambler and underworld character who lives in the neighborhood and that the immense quantity of contraband liquor was intended for the state fair trade.”

1928

In April 1928 Minneapolis played host to Dr. James M. Doran, Federal Prohibition Commissioner, who came to confer with S.B. Qvale, district administrator, and for an inspection of the northwest bureau. He had good things to say about Minnesota, saying it was “regarded as one of the nation’s driest states” and that “only a minute quantity of liquor is filtering through.” Most of the problem in the north was in the Detroit area.

However, the sore spot in our area was in the sale of soft drinks and ice (setups) “to persons known to be drinking.” “Dr. Doran predicted that eventually the United States will be completely dry, but admitted that this will take a long time.” He also predicted, “Prohibition is here to stay and is making itself felt as a material factor in the present social and economic condition of the country, which is better than anywhere else.” (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, April 21, 1928)

1929

Over in St. Louis Park, an unconfirmed rumor was that Dutch Reider had hot and cold running hooch in his bathroom, or so the neighborhood kids (and the police) liked to speculate, and he was raided several times. On July 19, 1929, he was accused of selling intoxicating liquor to one Ray Paulson. Officer Earl Sewall and four other officers executed the search warrant, arrested Dutch, and confiscated “a quantity of intoxicating liquor and one five Gallon jug.” Dutch pleaded guilty to maintaining a nuisance, and was fined $100. Making moonshine was a Federal offense, and Dutch could have spent some time in the Federal penitentiary.

1931

Ad for Hamm’s Malt & Hops (“For Food Purposes Only”). Jeff Lonto says, “Often those kinds of Prohibition-era products included directions on what NOT to do, otherwise you’ll have an illegal result.”

Minneapolis Star, April 29, 1931

1932

1932 joke: “Why did you name your baby Capone?” “Because he has no regard for the dry law.”

A couple of St. Louis Park Stories:

There’s the one about a Saturday night “party” at one of the speakeasies and how the one-man Park Police force took the drunks home with him rather than take the time to haul them all the way to the Minneapolis hoosegow, as it was too far. St. Louis Park’s two-cell jail was more of the “Mayberry” variety and couldn’t possibly handle the volume.

Even the Town Band got carried away, it seems. An oft-told story concerns a 4th of July engagement in Chanhassen. Ben Brown remembers, “The band caught the train in St. Louis Park and rode straight to Chanhassen. One member couldn’t make the train that morning, so he walked the railroad tracks all the way. He couldn’t locate the band, so he inquired as to where they might be. The people of Chanhassen wanted to know why he wanted to find the band, and once they found out he was a member, they ran him out of town without so much as an explanation. He soon learned that the band had arrived early, got drunk, and raised particular hell so they were all run out of town. And then this poor guy arrives late after walking from St. Louis Park and asks, ‘Where’s the St. Louis Park Band?’”

1933

REPEAL

Congress passed the Blaine Act, formally titled Joint Resolution Proposing the 21st Amendment, on February 20, 1933, initiating repeal of the 18th Amendment.

Meanwhile, on April 4, 1933, Congress passed the Cullen-Harrison Act (or the “beer bill”) that declared that 3.2 percent beer was “non intoxicating.” Previously, beer with more than .5 percent had been considered intoxicating. Beer could be sold starting on April 7, 1933.

Things went crazy! There was no regulation, no license mechanism set up, and “nite clubs” sprung up like toad stools all over Downtown Minneapolis and St. Paul, Excelsior Blvd. in St. Louis Park and Hopkins, and most Main Streets in most towns that are suburbs today. They had had crazy names, floor shows, jazz bands, and probably provided more than 3.2 beer, but who’s counting?

Beer was so in demand that you could even get it on tap at local drug stores and even at gas stations. Now there’s a good idea.

The 21st Amendment gave the regulation of alcohol back to the States. It had had to be ratified by the states, which took until December 5, 1933.

Prohibition had lasted 13 years, five months, and nine days.

1934

In early 1934 Minnesota passed a bill giving localities the option of allowing the sale of liquor, but also instituting certain statewide restrictions such as dry Sundays.

The only research I’ve done on this is for St. Louis Park. “Hard liquor” licenses had to wait until a Village general election was held in December 1934. On November 29, 1934, the “St. Louis Park Taxpayers Assoc.” placed a large ad in the Hennepin County Review urging

Vote For License!

On all sides of St. Louis Park liquor is being sold under license [legally]. It is therefore desirable that St. Louis Park should also vote for license in order that we be the better enabled to cope with the sale of liquor in the Village, protect our citizens, and at the same time derive some benefit from the sale thereof.

Reasons for voting to allow liquor licenses to be issued were primarily to collect revenue, control drinking in the village, discourage people from buying elsewhere, and doing away with the bootleggers. The electorate overwhelmingly agreed, with a vote of 1,165 to 473 on December 12, 1934.

THE EXCELSIOR BLVD STRIP

By 1934, Excelsior Blvd. had about six or seven (or 14?) beer joints that were open 24 hours, and the noise made it impossible for nearby residents to sleep. One such resident was Morton Arneson (1893-1982), who had bought three acres on Excelsior Blvd. and Quentin Avenue and established his nursery business, the first of five such nurseries on the Boulevard, at 4951 Excelsior Blvd. in May 1929.

In his memoir, Arneson told of one particularly hot night when the racket was worse than ever; the band in the speakeasy across the street (probably Walt’s Canteen, across Quentin) played three pieces on the banjo, one after another, and when they were through they started all over again. Finally, the family departed to a friend’s house way out of town to get some sleep. He suspected the Kid Cann gang and the police (and possibly Mayor James H. Brown) of being in cahoots. Regardless, although the law that required establishments to close at midnight, it was not enforced, and those who complained were told to go back to Minneapolis if they didn’t like it.

1940s

Ah, but an article dated February 6, 1942, tells us: “Council Serves Notice it will Tolerate No More Liquor Violations in Village.” The action came in the wake of a hearing where Henry Aretz was accused of selling alcohol at Bunny’s, although it was unclear whether the issue had to do with selling to a minor or selling on a Sunday. Many citizens gave their opinions both for and against yanking Bunny’s license.

The liquor business was put under attack in October 1945 when the Committee for Tax Savings, led by Hugh McElroy, called for a municipal liquor store. The attack was rebuffed.

Then there was an undated flier issued by the Liquor Dealers’ Assn., Al Lovaas, Chairman (Al of Al’s Bar). The flier was addressed to the Voters of the Village of St. Louis Park and made an impassioned plea to retain the status quo, citing revenue from the sales of liquor, dances license fees, pinball license fees and more. 67 people were employed full time, and 107 would be put out of work and on Relief if the bars were shut down. Tax revenue would be lost, and those who “want wines and liquors [will] step across the line to Minneapolis, Golden Valley, Edina, and Hopkins, where the same can be obtained.” The return of the Bootlegger was even listed as a possible threat if the legal, orderly, licensed and controlled conditions were eliminated. The barmen ultimately prevailed.

Former councilman Keith Meland explained that one reason for the success of the bars and restaurants along Excelsior Blvd. was a Minneapolis ordinance that did not permit liquor to be sold south of Franklin Avenue – see below for the Liquor Patrol Limits. Indeed only one liquor vendor existed in South Minneapolis, and that was the President Cafe, located across from the old Nicollet Ball Park.

Edina allowed no liquor, and the only place you could get it in Bloomington was the old Oxboro area south of 86th Street. The best place to buy your liquor if you were a resident of South Minneapolis was St. Louis Park. In addition, almost all of the Park establishments had combination licenses that allowed them to sale packaged liquor and sale by the drink. The Foo Chu, Jennings, Bunny’s, Al’s and the El Patio, among others, had combination liquor licenses.

1953

In an effort to put a stopper on prostitution, in the wake of a sensational trial, the City of Minneapolis decided to enforce an old ordinance that prohibited women from sitting at the bar alone. This did not make bar owners very happy, because they had to reconfigure their places to include more booths. Several said they had to tear up their bars. (Minneapolis Tribune, October 13, 1953)

1960

On February 11, 1960, the Minneapolis City Council passed an ordinance making it possible for 3.2 taverns to stay open and offer live music until 1 am. This ordinance was the result of a request from musicians’ unions and tavern owners to be allowed to offer music – without entertainment or dancing – after 11 pm without having to buy a $667 per year tavern license. The city recommended a new music license at $250. 80 percent of the people living within 200 feet of the tavern’s front door would have to approve the license, but not renewal.

A second ordinance mandated the cutting off of the playing of pianos, trumpets, bongo drums, and other instruments at 1 am in all-night restaurants. This ordinance stemmed from complaints about loud music coming from late-night pizza parlors near the U of M campus that served neither beer nor liquor. Such places could still use juke boxes, radio, television, or “piped-in” music. (Minneapolis Tribune, February 3, 1960)

II. THE DRINKING AGE

FIRST, THE VOTING AGE

During the Vietnam War, a cry for lowering the voting age was heard when 18 year-olds were drafted to fight but could not vote. In order for the voting age to be done across all elections, it was determined that it must be done by Constitutional Amendment. The 26th Amendment was proposed by Congress on March 23, 1971:

The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age.

It was quickly ratified by three-fourths of the states on July 1, 1971.

NEXT, THE DRINKING AGE

The drinking age had always been 21, even in 3.2 taverns. Now with 18-20-year-olds eligible to vote (and to be drafted), the ability to drink alcohol was studied in many states.

In Minnesota, On June 1, 1973, the age of majority – and thus the drinking age – was changed from 21 to 18 on June 1, 1973. Regulars at the bars were leery at first of the new teenagers, but kids flocked to the watering holes of Excelsior Blvd. and to discos like Uncle Sam’s. The Insider reported that many bars changed to a rock format to accommodate the new customers.

On September 1, 1976, the drinking age in Minnesota was raised from 18 to 19, perhaps because many 18-year-olds were still in high school.

On September 1, 1986, the drinking age was raised from 19 to 21, with a grandfather clause that allowed people who were at least 19 on that date to drink legally. This was done in whole or in part in response to a 1984 federal law that threatened states with the loss of 10 percent of their federal highway funding if they didn’t move the drinking age to 21.

III. LIQUOR LIMITS

A. Minneapolis

In 1884 the City of Minneapolis created geographic zones where hard liquor could be served. The so-called “Liquor Patrol Limits” were primarily downtown and part of northeast. The aldermen who represented the zones had the discretion to award liquor licenses, paving the way to bribery and corruption.

The Liquor Limits went into abeyance during Prohibition, since all bars were technically illegal and had been turned into “confectioneries” (candy stores), if that can be believed. People consumed a lot of candy during Prohibition.

When liquor was legal again in 1933, the limits were temporarily loosened. During that time, 37 liquor licenses were granted outside the Liquor Limits, snapped up by mobsters Kid Cann and Tommy Banks.

The Liquor Patrol Limits were finally eliminated in 1974.

B. St. Paul

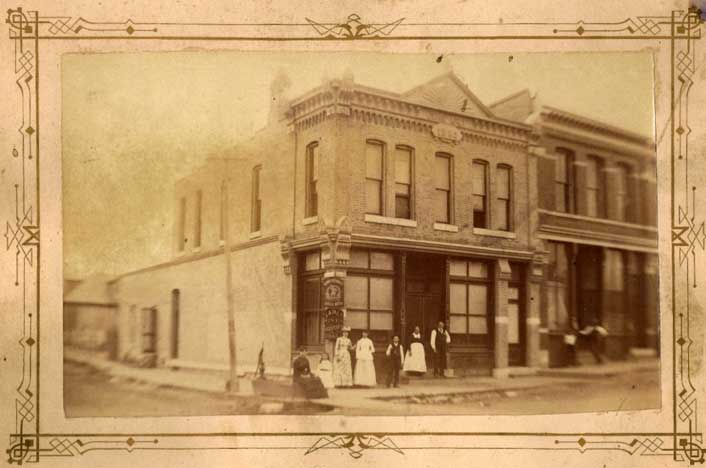

In 1893, the City of St. Paul also drew lines that determined where saloons could or could not be located. The following story comes from the St. Paul Globe (October 26, 1894), and Linda Bernin, the second great-granddaughter of John Arlt.

It seems Arlt ran a saloon in building he built in 1883 at 542 Ohio Street. Due to illness, in 1890 he converted it to the Samaritan Pharmacy, but got caught selling liquor (actually just beer) without a license and was fined $100 in July 1892. In November 1892 there was an ad for a druggist wanted, and then the drug store closed up. The local prohibition ordinance was passed in 1893, and in October 1894 Arlt wanted to open the place as a saloon again. But one of the boundaries was “200 feet east of Ohio Street,” which made Arlt’s property disqualified as a saloon. Petitions flew on both sides, but the City Council was not convinced to change the ordinance, and Arlt was out of the saloon business. (St. Paul Daily Globe, November 07, 1894) By 1901 the space was a grocery store.

John Arlt’s Saloon @1890. Image courtesy Linda Bernin

Building detail. Image courtesy Linda Bernin

The building still stands today, used as condos, but not nearly in its original splendor.

IV. B-GIRLS: A LESSON IN TRICKERY

The following comes from an article in the Minneapolis Tribune dated April 23, 1961. It describes what a B-Girl does in a bar to get a gentleman to open his wallet and buy the lady drinks.

In these bars [the Persian Palms, the Frolics, and the Saddle], customers are asked to buy drinks by girls … The drinks are served in shot glasses to the girls. Each drink is accompanied by a cola “chaser” in a second glass. The girls take the liquid from the shot glasses into their mouths and then spit the drink into the cola in their chaser glasses. They do not swallow the liquid.

The standard price for a single shot for the girls when last week’s check was made was 85 cents. A double cost $1.70.

The girls may ask the customer to buy them champagne. It cost $10 for a 13-ounce bottle and $20 for a 26-ounce bottle. In serving champagne, the bartender gives the girls a tall, frosted chaster glass with ice cubes in it. The girls take the champagne into their mouths and spit it into the frosted glass. When the glasses are filled the girls ask for another glass of water.

This is despite an ordinance passed by the Minneapolis City Council on April 8, 1960, that made it

unlawful for any female person while on any premises licensed for the sale of intoxicating or non-intoxicating liquor by the drink to solicit, induce, entice, or encourage in any manner any male persons not previously known to or acquainted with such female person to purchase for herself or other any alcoholic or non-alcoholic beverage, merchandise, or any other thing of value.

However, excluded were any “licensee, bona fide waiter, waitress, host, hostess, entertainer, or bartender regularly employed.”

The purpose of the ordinance was to cut down on prostitution, although some said that the B-Girl phenomena was a thing of the past. Unfortunately, there was a surge of prostitutes coming to the city – one theory was that it had to do with the Minnesota Twins coming to town.

The exemption for hosts, hostesses, and entertainers was removed in August 1961, and the first arrests were made that same month, although the women arrested were also seen picking their victims’ pockets at the Happy Hour Bar, 410 Hennepin Ave. They were each fined $100, stayed pending appeal. The whole thing seemed to peter out in 1962, and B-Girls became the butt of jokes for the most part in the sixties.

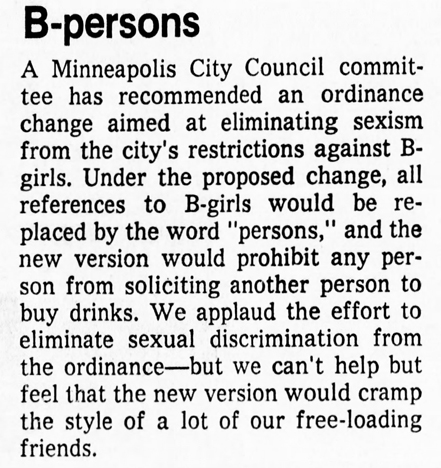

But on June 28, 1974, the Minneapolis City Council passed this:

Minneapolis Tribune

And…

Minneapolis Star, August 5, 1974

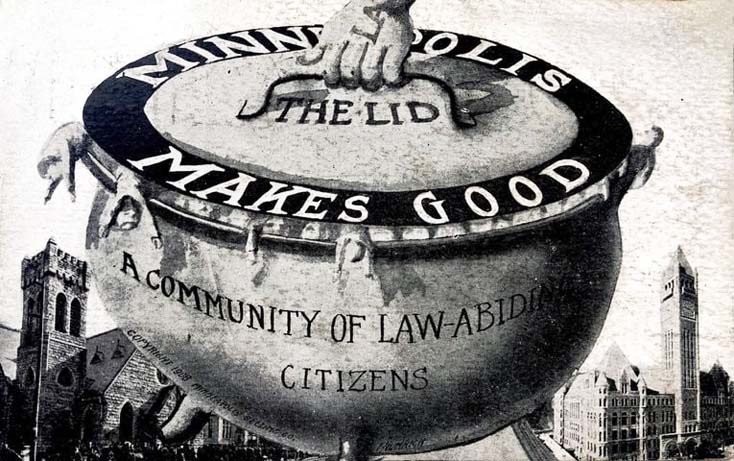

V. LID TIPPING

In the papers at the turn of the last century, you will suddenly find the term “lid tipping,” and if you’re like me, you’ll wonder what the heck that is/was. The first instance I found was a guy who was found guilty of lid tipping for letting his date drink hard alcohol. It had nothing to do with his hat or his manners or getting his girl drunk. He was simply breaking the law, or tipping (breaking) the “lid” (restriction/law). Apparently in Minneapolis at the time it was illegal for women to imbibe in the spirits. The more I looked through the papers for the term, the more different kinds of examples I found. But it was all the same thing. Merely breaking (mostly alcohol-related) laws.

Most of the so-called lid-tipping laws were enacted to either protect women or prevent prostitution, it would seem. At times women were not allowed to enter bars unescorted by men, or they could not sit at the bar but had to sit at a booth. The rather gruesome graphic below illustrates the lid keeping the bad guys from getting out of the cauldron of immorality. Or something.

From a 1908 postcard, courtesy Stewart Hall

One wag said that there was not much lid-tipping in St. Paul, because there wasn’t much of a lid to begin with. Probably true – anything went in St. Paul.