E Floyd was not a musician (many will attest to that) but as the first Hippie in Minneapolis, he deserves some recognition on this site. Although he would eschew the term “hippie” at one point, Johnny Hanson (and I quote Mr. Hanson a lot here) says that in 1966 he sold black and white posters of himself for a dollar with the title “Minneapolis’s First Hippie.”

FLOYD EDWARD NACHTWEY

The artist who would become E Floyd was born Floyd Edward Nachtwey, the son of Floyd Paul Nachtwey and Clara Lucy Thomalla. The younger Floyd’s birthdate seems indeterminate, but he was born in about 1942 in Wisconsin.

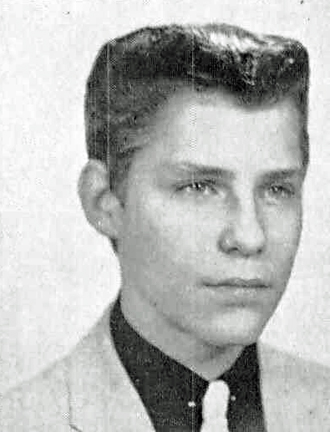

Here he is in the North High Yearbook, 1959.

In the index it reads: Student Council, Bank — Artist and Publicity Manager, Apparatus, Wrestling, Class Play Crew.

We next see him in print in June 1964, for no particular reason. It was in an article about bikinis and hairstyles on the beaches in Minneapolis, including Beatle haircuts. And although several people were interviewed, Floyd was not quoted, nor was he sporting a Beatle haircut. Nevertheless, his picture (and address, girls!) was printed. Weird.

June 29, 1964

According to one article, after high school he became a professional gymnast (do gymnasts get paid somewhere?).

He contracted polio sometime in 1964 and spent time at the Sister Kenny Institute. This seems to be an anomaly, since his generation was almost universally vaccinated for polio in 1955.

THE PARANOID GALLERY OF ART

By July 1965 Floyd had established the Paranoid Gallery. At that time it was located at 4181 Lyndale Ave. No. Doesn’t actually compute on the map, unless it was north of 42nd Street, in which case it is now a commercial building. In any case, our man was now using the name E Floyd, and in July he reported to Minneapolis police that burglars had broken in and stolen three oil paintings and a sculpture he valued at $250. The sculpture, made of plastic and bronze, was called “A Crouched Man.”

The three oil paintings, each about 18×24 inches, are a street scene entitled “Willow Street,” “A Vertebral Head,” showing an X-ray-like view of a head, and “Time Out,” an abstraction in colors done by Nachtwey as part of a therapy project while he was a polio patient at Kenny Institute during the past year. (Minneapolis Star, July 14, 1965)

By January 1966, the Paranoid Gallery had moved to 2 N. 7th Street at Hennepin Ave. It was located in an abandoned barbershop, and one witness said that a barber chair was still down there.

Johnny Hanson: “You can’t see the stairs but they were on the left, down from the sidewalk on 7th Street under that Cliquot Club sign.” It took a quarter and not a little nerve to go in. Johnny again:

We were given to teenage curiosity and went down the steps into the darkness. There were spotlighted various paintings and drawings. Out of the shadows, stepped E Floyd: black leather pants, purple paisley shirt, very long hair. He handed us each a carrot and said, “‘It’s fabulous, Fatman!” …but we came to realize that he called every fellow “Fatman.”

Floyd was featured in the Tribune in a series about gallery owners, which indicated that “he has come to an involuntary parting of the ways with the Minneapolis School of Art.” He opined that “modern art is phony,” and said that “his gallery is for the common man; he wants no artsy-craftsy salon.” (Minneapolis Tribune, January 23, 1966)

Minneapolis Tribune, January 23, 1966

ZAPPA

Was Frank Zappa influenced by Floyd? His album “Freak Out” was released on June 27, 1966, and in the liner notes, under the heading “These People Have Contributed Materially in Many Ways to Make Our Music What it is. Please Do Not Hold it Against them,” the name Floyd is there between the names The Bokelmans and Ernie Tosi. Is that our E Floyd? I found no documentation that Zappa performed in the ‘Cities before his appearance at the Guthrie on July 13, 1969, but that doesn’t mean anything.

NO PROTESTER

On September 6, 1966, the Minnesota Committee to end the War in Vietnam held a demonstration that drew about 100 people to the corner of 7th and Hennepin. The Minneapolis Star noted that the only person there who “fit the stereotype” of a protester was E Floyd, complete with “a beard, shoulder-length hair, and a sleeveless leather vest worn without a shirt.” He had nothing to do with the protesters – it was just his corner and all. When asked about the issue, he said that the “situation is too complex to assess in black and white terms.”

E’s polio probably kept him out of the draft, and he was going to school, albeit art school.

A FRIEND IN FLANAGAN

By the fall of 1966 he had become a frequent topic in the column of the Minneapolis Star’s Barbara Flanagan, who championed the improvement of Downtown. Floyd was all for that cause, but Flanagan said that he gave like-minded businessmen the “jitters” when they “take one look at Floyd in his black satin blouse, tight black pants, knee high boots and shoulder-length hair.” He countered with the claim that he had 18 $200 suits in his closet, doesn’t drink or smoke, and has no police record.

He told Ms. Flanagan that he wanted to open a coffee house – a place for kids to go – called the Paranoid Gallery of Sound, serving coffee and loud music. The column revealed that Floyd was living with his parents, and that you could call him E or Floyd, whichever you chose.

As for his long hair, he had decided to let it grow until he could once again do a back flip. That goal came and went, but he decided to keep it long, claiming it was easier to care for. He also bemoaned the way that men had become “so prissy and feminine. They don’t even eat like men.” And a man crossing his legs “like a woman” was bad for your circulation and uncomfortable. (Minneapolis Star, September 8, 1966)

September 8, 1966

STORIES FROM 1966

I went along when my friend Bill interviewed E Floyd for our high school newspaper in 1966. E Floyd freely shared his philosophy of life and played for us an LP recording of Frank Lloyd Wright lecturing about education. The school paper wouldn’t print the interview so we started our own underground paper.

George Ostroushko:

I was taking Commercial Art at Vocational High when I first met E Floyd in 1966. He was very impressed with my art and offered to put it in his gallery. We became best of friends and I always credited him introducing me to the hippie lifestyle that I embraced. A couple of my pieces did end up selling at the gallery.

And this:

The gallery stayed open for a couple of years with no apparent means of support. It was said that E scrounged stuff from the dumpsters of MCAD (a local art college) for his gallery (“found art?”) but if you went down and acted interested, E would talk about “his” art with you. E was more of a beatnik/hipster than an artist, even sporting shades and a goatee. E was about ten years ahead of the curve. Soon there would be lofts and galleries throughout the nearby warehouse district, while E had disappeared without a trace.

Jay Hamburger:

Floyd and I met while I worked in the Music City store at 7th & Hennepin during parts of 1967-’69. I then opened “What’s Up,” a head shop/gift boutique on the second floor balcony of the music store, and it was then that Floyd and I saw each other regularly. He was a very weird, iconoclastic arty odd-ball…..and I was drawn to him. I was hip, but not yet a hippy. I had worked for a couple of years as Promotion Manager for 100 record labels in the six surrounding states, and had experienced lots of music business excesses and weirdos….and E was like flypaper for me. Not only was his weirdness appealing, but he freely validated me for being a counter-cultural soul…..although my style was so much straighter than his. I had already felt the condescending attitude of some insecure wannabe hippies, so feeling validated and respected by this seemingly genuine article hippy was satisfying.

His gallery had no plumbing facilities, so Floyd was clever to create an ersatz toilet and “kitchen.” He opened mechanical access within the walls to uncover the sewer line for the building. Opening the 6” clean-out plug gave him a fair shot at dumping his waste while perilously balancing on the 6” pipe over a drop of several feet. His girlfriend also used it. E also had some clever means of heating water for coffee and tea, at a time when such equipment was scarce. I remember the pride with which he made my first cup of his coffee.

We would talk at length about the state of the World….. the Universe and the wonder of pharmacology. He always seemed a bit removed when he spoke….as though he was also secretly monitoring life on another planet…..or perhaps just preoccupied or stoned. I did not often see him taking drugs, so I could never tell what was his baseline. I was especially fascinated by his mustache which grew from his lip down through his beard to his clavicle in two wispy threads which he sometimes braided.

I left Minneapolis in 1969, moving back to the area in 1972 working as a photographer. I had limited contact with E and departed in 1973.

FLOYD AS HIPPIE?

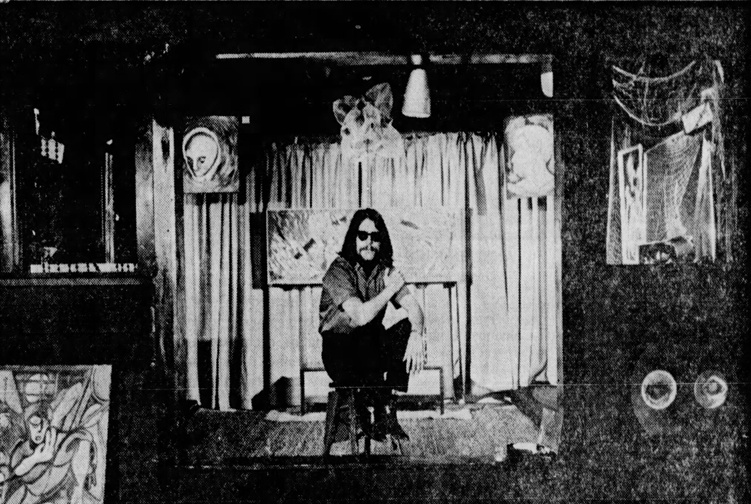

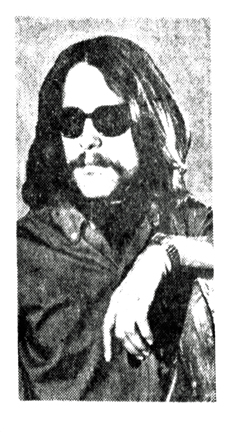

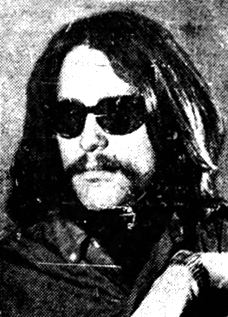

Another article about Hippies featured the photo below of E. The caption reads:

Reluctant to be called a “Hippie” is 25-year-old E Floyd, operator of the Paranoid Gallery of Art… A student of sculpturing at the University of Minnesota, Floyd says most people consider him a Hippie because of the way he dresses. He distains those he calls “Hippies” because he feels they do nothing. A “true Hippie,” he says, should use his freedom from conventional society for creative self-expression.

October 8, 1967

ANOTHER SIDE OF FLOYD

Floyd was featured in Barbara Flanagan’s column again on November 10, 1967. It seems they both agreed that Hennepin Ave. needed a new image, and Floyd had changed his.

“I’m changing my image,” he said. The new Floyd has trimmed his hair and tied it back with a bow a la Lafayette or George Washington. It looks good. He’s also wearing pin-striped business suits with vests. “I’m changing the name of the gallery,” he said. I waited. “The new name,” he said, with a straight face, “is the Seventh Street Gallery.” I was shocked. How could he? “I want the folks in Fargo and other places to come in and see the art,” said Floyd. “The other name may have scared them away.” So would the other Floyd.

Yesterday Floyd was working on his new sign and making plans to paint the steps down to the gallery along with the rest of the facade a bright and friendly green. “Green is a good color,” said Floyd. “It means money and happiness and life and newness. I was inspired by the friendly green tree up there.” He pointed to Midwest Federal’s great green tree sign on the building above with the news bulletins whizzing by it.

FLOYD vs NICOLLET MALL

Apparently E’s idea of Downtown improvements didn’t coincide with those of the Downtown Council. On November 20, 1967, the Nicollet Mall was first opened. Gary Schwartz:

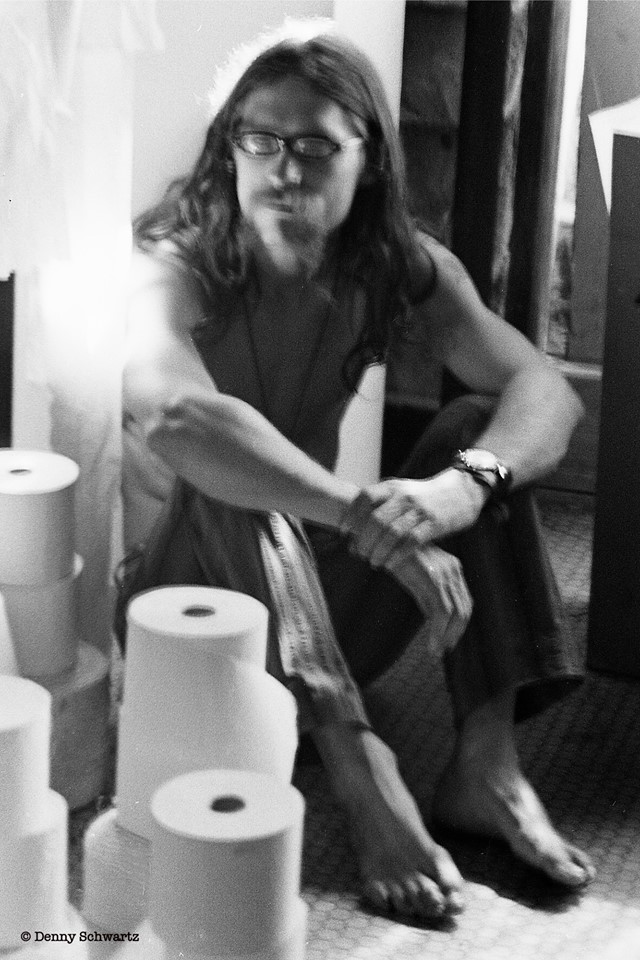

As a statement E Floyd got a group together on the first evening that the Nicollet Mall was open and toilet papered, strung twine, and filled a couple fountains with soap so the water bubbled over. I sort of remember this happening in front of Donaldson’s. It didn’t get too far before the police nabbed him. Here’s a photo of him with toilet paper supply ready to go.

Photo by Danny Schwartz courtesy Gary Schwartz

So much for his clean police record?

NO SOUL!

Ouch! On an extended column on Soul, Will Jones took it upon himself to list Minneapolitans who had and did not have it. E Floyd was included in the category “Surprisingly Without Soul.” But then again he also said that Cecil Newman and AB Cassius had no soul. Go figure. (Minneapolis Tribune, March 15, 1968)

Ah, but Barbara Flanagan never gave up on Floyd, calling him “my friend” and “among the right people on Hennepin Ave.” in her column of May 21, 1968. She reported that he was planning an art show, in time for the Aquatennial, called “Top of the Lot.” “It’ll be on top of the Radisson parking ramp, and only the top artists will be involved.” To make it even groovier (Barbara’s words, not mine), nothing could be entered that was smaller than six feet.. “Everything should be bigger,” he said. Some of the artists he had in mind were Charles Huntington, Katherine Nash, and Siah Armanjani. Did it happen?

ROCKIN’ BLOCK E

Making waves – this time sound waves – was our friend Floyd in the summer of 1968. Seems that on July 21, 1968, Floyd and friends Neil Gelvin and Rick Steele were playing music inside the gallery in a band they called FOME: Family of Man Expanding. Although the doors were closed, they were arrested for “breach of the peace (unnecessary noise).” Arresting officer Greven called six, count ’em, six other officers for backup after hearing “amplified guitar music emitting from a musical instrument” from about 80 feet away. “He denied saying on previous occasions that he intended to put the Gallery out of business.”

In court, the only other police witness said he could hear Greven just fine when he briefed him on the situation. A reading of the breach of the peace ordinance revealed no mention of noise, and Judge Herbert Wolner dismissed the charge without any witnesses or arguments for the defense.

Although the judge did not give a reason for the dismissal, Bob Lundegaard of the Tribune speculated that the dismissal came from the fact that nobody else complained, and no one was congregating to listen. (Minneapolis Tribune, August 15, 1968)

The dismissal probably disappointed Floyd, no doubt ready to defend himself admirably, although he did say to the press that “his music wasn’t any louder or more unnecessary than the canned music on the Nicollet Mall. In fact, he said, he plans a demonstration on the mall to demand elimination of the music.”

Oh, and reporter Gwenyth Jones noted that Floyd showed up for court in “a black satin shirt with a purple brocade stole flowing over one shoulder.” So much for the $200 suits? (Minneapolis Star, August 15, 1968)

August 15, 1968

Oh, and more than one person has speculated that Block E was named after E Floyd. Cool idea.

GOODBYE GALLERY

Barbara Flanagan again, reporting that E Floyd, a Hennepin Ave. Landmark with the “flowing hair and Zapata moustache,” called to tell her that he was going to go live on an island in the South Pacific. “I got my college degree in December. I got married in January. Now I’m beginning a new life away from noise.”

He left his gallery to a young couple from Mankato, who planned to reopen it on March 1, 1969. “They’ll help keep my spirit there,” Floyd assured her. “All I could say was ‘bon voyage, Floyd.'” wrote Barbara. (Minneapolis Star, February 20, 1969)

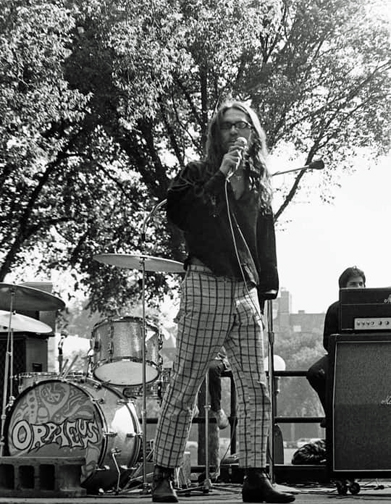

Perhaps the bon voyage was premature. There was a story about Floyd jumping on stage at a performance (one of the Love-ins?) at Loring Park, but as was mentioned, Floyd wasn’t much of a singer.

Loring Park, 1969. Photo by Gary Schwartz

1969

TZAD WANTED

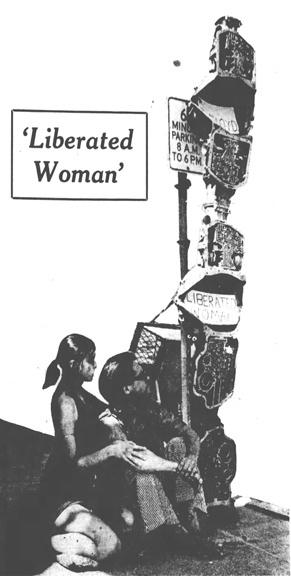

This in from August 1970: Floyd had moved himself and/or his studio to the College Inn Hotel in Dinkytown (now the site of Dinkydale), and one day a nine foot high aluminum sculpture called “Liberated Woman?” went missing. The piece had been exhibited on Nicollet Mall the week before for the “Soul of the City” event. The sculpture was taken from near the Hotel. Floyd said it was a project for an art course he was taking at the U.

Then came a knock at the door and he found a package that included a pink negligee and a ransom note, demanding, not money, but his girlfriend “Tzad” (nee Patricia Kania). He went to the police but they were sure it was a joke. Floyd did not think this was funny.

Two days later it was reported that the statue had been found near Coffman Union, and Floyd did not have to surrender Tzad. That article said that the piece was a satire on the women’s liberation movement. (Minneapolis Star, August 27, 1970)

Tzad, Floyd, and his statue, August 27, 1970

In December 1970, Floyd was displaying his art at Earthworks, 407 Cedar Ave. on the West Bank.

PIER SCULPTURES

In her expanded column of January 21, 1971, Barbara Flanagan reveals that Floyd had escaped Hennepin Ave. for an island in the South Seas, as he had promised, but deemed it “too quiet,” so he was back in Minneapolis – for now.

He had settled in Dinkytown – his new gallery was also a basement affair at 1325 Fourth Street SE (Facebook fact). That building looks like this now:

There he concentrated on his sculpting. In a recent one-man show, his catalogue read, “E Floyd is more a myth than a real person. therefore, in the eyes of mass culture, I must be a bit phony.”

And in typical Floyd style, he had an idea to improve his home town. Seems there were two old bridge piers in the Mississippi River below the Stone Arch bridge. Floyd thought that there should be a piece of sculpture on one or both of the piers.

It would stand 15 feet tall atop the 20-foot pier and catch the sunlight. Oh, it could be glorious! It would be in bronze, a fiery bronze in the sun. It would represent earth, air, fire, and water. And it would also represent the beginning – of life, the river and the city.”

Although some people found his abstract sculpture “naughty,” he insisted that

It isn’t – It is universal life. I call it “E-Line.” The “E” is for eternal. And it’s a play on words… E-Line, feline, lion, Lyon. It is everything and nothing. When somebody greets me with “Hi E,” that’s the highest “Hi” I can think of. E-line is the modern phoenix bird. It means regeneration and rebirth. That’s what is happening to Minneapolis. The city started on that site. We should commemorate that.

All he needed was permission and about $5,000, with a goal of installing the sculptures by helicopter by November 1 – All Saint’s Day.

This isn’t junk sculpture or computerized art. This sculpture was made by my hands. It is symbolic, not specifically, but particularly. I learned when I went away that you don’t have to go somewhere else. Michelangelo worked where he lived. Minneapolis is my home. This sculpture fits here so well. So do I.

Flanagan thought it was a good idea, saying “Floyd [thinks] big and beautiful thoughts about our town. I wish more people would.” (Minneapolis Star, January 21, 1971)

Floyd points out site – January 21, 1971

STUDENT ACTIVIST

In a long article published on June 7, 1971, in the Minneapolis Star, Richard Gibson reported that Floyd had been charged with seven counts of disturbing the peace by members of the art department faculty at the U of M.

Most of the charges stemmed from a fine arts faculty meeting on October 16, 1969. There he allegedly called sculpture professor Katherine Nash an obscenity. When professor Malcolm H. Myers tried to throw him out, Floyd was accused of kicking Myers in the groin with both feet. Security came and Floyd left, but he climbed the building and appeared at a second-story window. Nash testified that the fact that he could climb a building especially distressed her – Floyd had told her that his polio had inhibited the use of his hands, and she had been lenient with him. Now she felt “duped.”

Floyd’s version of events was that he had entered the meeting when he heard the words “independent study.” When he was told to leave, a wrestling match ensued, and someone knocked Floyd down. He said that the professors exaggerated his ability to kick Myers, and that the second story window was only about 10 feet from the ground. He said he had just stood on the shoulders of a friend to stick his head in the window and say “You can’t stop me.” His version was corroborated by a professor who was at the meeting but was no longer employed at the U.

Floyd was also accused of disrupting three other faculty meetings. At one he appeared with tape over his mouth. Rather than a message that students’ voices were not heard, Floyd asserted that “It was to indicate his sincerity to listen and not to interject his opinions.”

Floyd with his mouth taped – Photo by Minnesota Daily

He was also accused of:

- Disrupting an art seminar

- Disrupting a committee working on a constitution for the Department

The accusations were brought before the Committee on Student Behavior, which was composed of five professors and two students.

Floyd handled his own defense, saying that his actions were constructive and that the University should award him an honorary doctorate of fine arts. At the time he was about 30 credits short of a bachelor of fine arts degree.

He wanted students to have a say in critical decisions, such as which classes they must take, class size, and which professors should be hired and fired. He charged the student body with apathy and said that his goal was not to disrupt but to raise questions.

The Committee found him guilty on two counts and recommended that Floyd be placed on probation for the upcoming fall quarter. He could have been expelled if found guilty of all counts. Gibson wrote:

The case is significant in that it was the first prosecution under the University’s new student conduct code. And since Floyd’s case questions a student’s role in determining his education, it could set a pattern for future student involvement in decision making at the University.

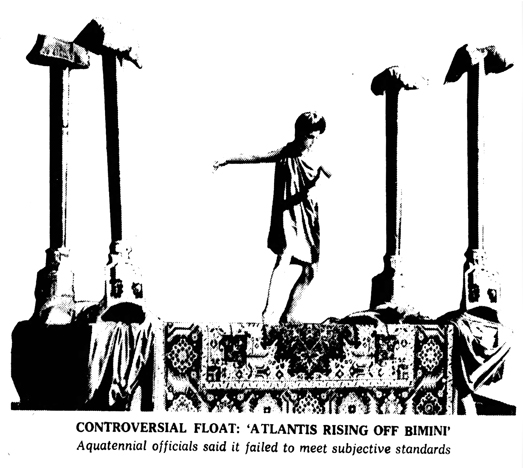

FLOYD vs. THE AQUATENNIAL

Picture this: It’s July 17, 1971, and E Floyd has entered a “float” in the Aquatennial Grande Parade. As described by the Minneapolis Star:

The float consisted of a trailer towed by a small van. On the back of the van was Floyd, playing a set of steel drums. On the trailer was a Persian carpet, several columns, a piece of sculpture, some purple acetate drapery, and Floyd’s girl friend dancing a ballet. The whole affair was titled “Atlantis Rising Off Bimini,” in keeping with the Aquatennial’s Caribbean theme, Floyd said.

He applied for and received permits to participate in both the Grande (daylight) and Torchlight (nighttime) parades, but after Aquatennial officials saw the actual float, they denied him the right to participate in the Torchlight parade. One said that they would have pulled him from the Grande parade but it was already wedged between two marching bands and about to enter Parade Stadium. They sent him a notice just before the Torchlight parade that his permit had been cancelled.

Floyd did not take this sitting down, and took the Greater Aquatennial Association to conciliation court for repayment of his expenses and an explanation from officials for why his permit was pulled. James Stone, an Aquatennial Vice-Commodore, represented the Association at the session on October 19, 1971.

When asked by referee Wayne Pokorny what was wrong with the float, Stone replied “Appearance. It didn’t appear to meet standards of appearance. It was detrimental to the other floats on which many hundreds or thousands of dollars had been spent. These are subjective standards, I must admit.”

“It was a crummy float?” asked Pokorny. “Yes, it was a crummy float,” Stone asserted.

Floyd estimated his expenses to be $350, not including the $50 that girlfriend Tzad had to pay her ballet teacher for choreographing her dance, or damage to the carpet from excited kids who spilled their treats all over it. Stone’s attorney estimated Floyd’s expenses at $30.73. “I’m not a businessman, I’m an artist,” said Floyd. “I don’t think in terms of cost.”

Floyd charged that the Aquatennial parades were discriminatory against creative people who don’t have the money to build the big floats. He said his float got tremendous applause from the crowd.

In fact, when the Aquatennial was over, one Richard E. Reed from St. Paul wrote a letter to the editor of the Minneapolis Star, calling the Grande parade an “unintentional caricature of American society.” He said the biggest applause was given to the man cleaning the horse poop from the street, saying that “He was one of the only two real, relevant expressions in the whole parade. The other was E Floyd’s Mystery Ballet. He was intentionally making fun of the whole, sordid, archaic mess.” (Minneapolis Star, July 24, 1971)

It turns out that after he was expelled from the Torchlight parade, he followed it anyway. Floyd explained that he was just using the most expedient route home. The referee called the point irrelevant.

But ultimately Floyd didn’t win anything in court, and his attorney, Richard Oakes, called the decision “another victory for the plastic people” and “indicated that his client would appeal. (Minneapolis Star, October 20, 1971.)

DOING HIS OWN THING

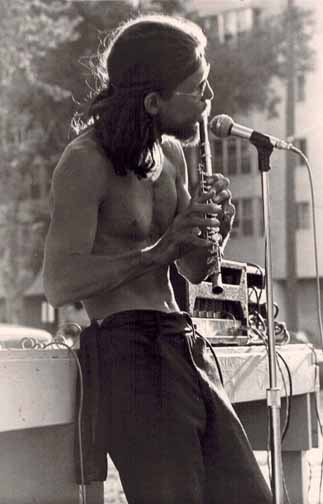

On Sunday, September 5, 1971, Loring Park was the site of “Bottleneck II & the First Minneapolis Open Air Resource Catalogue, organized by Barry Knight and sponsored by the Center Arts Council of the Walker Arts Center.”

It was a kind of living Whole Earth Catalog, if you remember that, with about 50 groups at tables handing out literature and educating people on topics like recycling, the arts, food, technology, health, and housing. Members of the Nancy Hauser Dance Company “frolicked,” and music was provided by the Whole Earth Rainbow Band, the Bumblebees, and Michael and Anthony Hauser.

Floyd wasn’t the booth type, but was irresistible to cameramen, and was photographed “[wandering] through the crowd playing his flute despite overwhelming competition from a rock band.”

Sept. 6, 1971

Speaking of flutes, the photo below is labeled “E Floyd plays flute in park at 6th and Cedar, part of West Bank Summer Arts Festival.”

Photo copyright Mike Barich

On April 6, 1972, Floyd interrupted a meeting of the State Constitutional Study Commission, which was considering an amendment guaranteeing equal rights for women and people in state institutions. Floyd distributed a statement “asking for acceptance of homosexuals.” (Minneapolis Tribune, April 7, 1972)

The last we hear of Floyd living in Minneapolis is on September 5, 1972, when the Minneapolis Star asked local personalities to write their own epitaphs. Floyd, described as “artist and opponent of bureaucracy,” wrote:

In Dyolf’s time

Eapolis was a mini-city

Just as Esota was a mini-state

HAWAII AT LAST

By June 1974, Floyd was living in Honolulu, finally on his island, but he was still in touch with his champion, Barbara Flanagan. He told her that he was running for Congress, and was designing a rainbow flag for his adopted state. He was so enamored of Hawaii, in fact, that believed that it should be the center of the world, and instead of Hawaii paying taxes, the world should pay taxes to Hawaii.

On August 18, 1976, Floyd tried to file as a candidate for Congressman from the First District of Hawaii. He tried to file as an indigent, thus avoiding the $75 filing fee, but was denied a place on the ballot. The problem was that he failed to read the fine print, which said that in order to file as an indigent he had to submit a petition signed by at least .5 percent of the registered voters in the district.

Well, either Floyd either knew that and wanted to test the law or he didn’t know it. Either way he sued the Lt. Governor and the State Elections Administrator, and the case went to the State Supreme Court. Cut to the chase, on August 16, 1978, the Court found in favor of the law, and Floyd never became a Congressman from Hawaii. Imagine if he had!

SETTLING DOWN

Barbara Flanagan was still in touch in 1977, reporting that Floyd had come home to visit his parents. She noted that he had cut his hair, shaved off his beard, and was preparing to run for Lt. Governor of Hawaii. He had made it a point to visit the policemen who had hassled him during his days on Hennepin Ave., saying “They’re the only friends I’ve got here, and I think they were glad to see me.” (Minneapolis Star, November 29, 1977)

Barbara Flanagan was still in touch, perhaps for the last time, in August 1978. His latest idea was that, since there is an alert system about bad things (like tornadoes and such), why not have alerts about good things, like rainbows? He reported that he had started a campaign there with local weathercasters. (Minneapolis Star, August 17, 1978)

Tom Hamburger tells us that Floyd ran for U.S. Senate from Hawaii in 1982, and won 2.9 percent of the vote.

In 1995 to 1996 he lived in Wailuku, Hawaii

From 1997 to 2005 he lived in Makawau, Maui.

E Floyd died on March 1, 2014, in Hilo, Hawaii, at the age of 72.

His wife was listed as Pauline Bernier. According to Ancestry.com, the obituary lists three children:

- U Krs-Krs

- O Krs-Krs

- Trinity

CODA

I am happy to report that E Floyd’s daughter Trinity saw this article and contacted me to say that it was interesting to see a different perspective on his life. I asked her if there was anything about his life in Hawaii that she felt that she could share, and told her that there were still a lot of people in Minneapolis who remembered him and who had been influenced by him. On October 5, 2019, she posted the following on the Old North Minneapolis Facebook Page. Thank you so much, Trinity!

Hi, I’m E Floyd’s daughter. His last name is Nachtwey. He moved to Hawai’i in the late ’70s, and married my Mom. He had two daughters and two sons. Never a dull moment with my Dad around. He got Leukemia and passed away in 2014. As far as I know he never was able to do a back flip again. He said he liked Hawai’i because the neuropathic pain from the polio wasn’t so bad in the warm weather. He raised an amazing family. Things weren’t perfect of course like with any family but I can honestly say I wouldn’t be who I am today without my Dad. I definitely wouldn’t be as artistic or musical without his guidance. I remember hearing stories about his adventures in Minneapolis. I would say he calmed down some what after having four children but I will also add that he definitely always had a cause he was fighting for.