Battle of the Red Barn

May 6, 1970

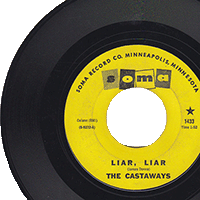

You may wonder what this topic has to do with local music, but for years I thought they had torn down the Scholar to build the Red Barn. I was wrong, but here it is anyway….

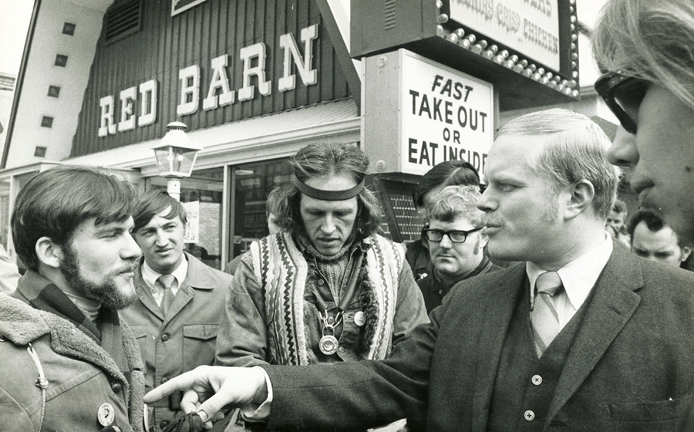

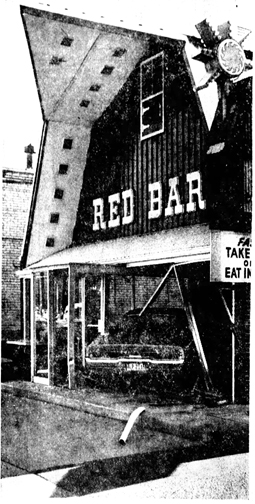

The Red Barn was a fast food chain that looked like … a red barn. There were several of them in the Twin Cities, fitting oh-so-subtly into the decor of any neighborhood.

Some neighborhoods loved them. The one below, at 8901 Penn Ave. So. in Bloomington, was beloved and is missed by the community.

But when the company wanted to put one in Dinkytown at the University of Minnesota, all hell broke loose. The Red Barn was planned for 1407-1411 Fourth Street SE.

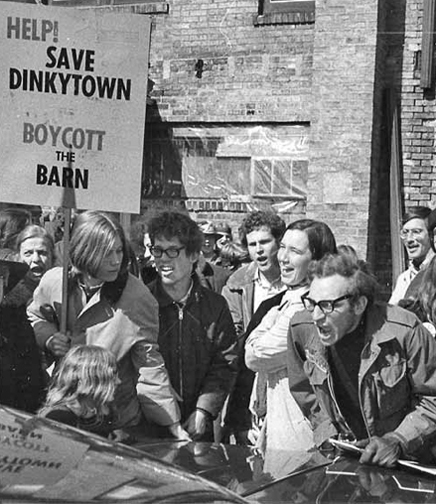

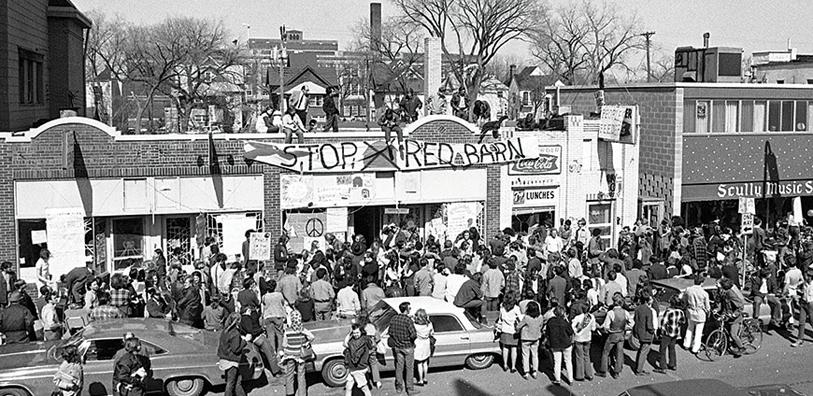

To show their displeasure, on May 6, 1970, Dinkytown residents occupied Fourth Street to protest the ugly fast food restaurant that was going up. The May 8 issue of Hundred Flowers included a fairly comprehensive account of the protests:

- John Teeter, a “student of life,” drove a rented 1970 Charger through the window and into the kitchen of the Red Barn at 313 Oak Street SE.

- Rocks were thrown at the Red Barn on Lake Street, breaking five windows.

- Protesters were deterred by cops on Snelling.

- Meanwhile, back on Fourth Street, there were about 175 cops, searchlights, and a helicopter, which protesters called a “whirlypig.”

I had some good links in here, but they have a habit of going away, so I will reprint the story from one of them here in case it disappears as well. The article below comes from the Triangle Park Neighborhood News Network newsletter, December 2003, and was written by Bob Germaine, with research assistance from Hannah Germaine.

Please note that the full-length documentary mentioned below, called The Dinkytown Uprising, premiered at the 2015 Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival.

Burger barn beef reheated:

Film project documents 1970 Dinkytown Red Barn protest

The subject of the conversation is Dinkytown history. Al Milgrom’s face is afire with serious discourse as he punctuates each statement with a friendly but passionate glare.

The Southeast film aficionado has ducked inside Espresso Royale, escaping a thin mist, and made his way to the back of the coffeehouse. He has dropped his fedora on a nearby chair, brushed back his long silver hair, taken a seat and started talking about Dinkytown and the Red Barn protests of 1970.

“There’s a long list of people who have never heard of these protests,” says Milgrom. “But it’s a story that left others stunned and would live in their minds for years to come.”

The story began 33 years earlier, just around the corner from this cafe. Milgrom, with a light 16mm Eclair camera, recorded events that are among the most dramatic Dinkytown has seen.

His short film, “When the Red Barn Came to Dinkytown,” premiered last month at the Oak Street Cinema; it’s a first step toward a longer documentary.

The short tells a capsule version: Protestors occupied a building that had been vacated by small, independent businesses, and was now slated for demolition to make way for a national hamburger chain called the Red Barn. Before the spectacle was over about 70 arrests were made, a car was crashed into another Red Barn restaurant in Stadium Village, windows were smashed at yet another Minneapolis Red Barn, and many lives had changed direction.

People had chased corporate fast food out of Dinkytown–at least once, if not for all.

It was 1970: by any measure a monumental year in American history. Vietnam protests grew in number and intensity as hundreds of fallen soldiers arrived home each month in body bags. A nation that had been promised de-escalation in Southeast Asia learned that Cambodia was to be invaded. Rage had become a plentiful commodity.

Amidst this chaos, the Red Barn became a symbol, perhaps, of how the citizens of Dinkytown could at least control their own neighborhood. The invasion by corporate America was a target within their sites, not a half-world away in Southeast Asia.

Planning for a Dinkytown Red Barn began in March, when five small merchants were forced to vacate buildings at 1307-1311 Fourth St. SE in preparation for their demolition. Opposition to construction of the Red Barn grew quickly. Though McDonalds and Burger King had by then laid claim to two corners in Dinkytown, many saw the Red Barn concept (as seen at several Twin Cities locations, including Oak Street SE) as too kitsch for this off-campus Bohemia.

On April 1, in an effort to prevent demolition of the building, protesters began their occupation of the buildings, which they renamed “People’s Hotel.”

“We were searching for democracy for the neighborhood,” said occupation leader David Pence, now a doctor at Abbott-Northwestern hospital, in a recent interview. “This was a reaction to Kent State and to the invasion of Cambodia.”

The event commanded heavy media coverage. Minneapolis Star reporter Molly Ivins, now a syndicated columnist, spent a night at the People’s Hotel.

Although most of those occupying the buildings were younger than 30, their efforts led to a groundswell of support from an eclectic group that included Dinkytown merchants and local residents. Former Southeast resident Diane Lassman remembers bringing casseroles to the protesters.

If the occupation site was the Alamo, then Pence was Jim Bowie. According to a local news report in early April, Pence told a crowd, “We will not move, and will not comply with the order [to vacate the building]. … The struggle has to be in the streets, and the people of Dinkytown should have the say on this building.”

In a recent interview, Pence said, “The first problem I had were the 15- and 16-year-olds who wanted this to be a war. They had Molotov cocktails. … One problem was to try to disarm ‘my teenage boys’ who wanted to fight them, fight the police.”

On April 20, 1970 the occupation intensified as Hennepin County District Judge Leslie Anderson ordered the group to end its occupation or be held in contempt of court. Many of the occupation forces reportedly then vowed to return to the site, marching from the court, chanting, “Ban the Red Barn, it’s a social disease.”

Thirty-three years after the protest, Pence admits, “It was a little bit of mob rule, which on reflection was not entirely right. … Our position, on reflection, was pretty untenable.”

Southeast Minneapolis resident Janet Lund remembers that the protests “brought such a mix of people. Middle age, older people, high school students–all types of people … people that had never been involved in any protests before. People thought, at that time, that you really can change things by protesting. And they did, at least that time.”

Then came May 6, 1970–one week after President Nixon told a national TV audience about the Cambodian invasion; three days after National Guardsmen fired 67 shots into a group of Vietnam protesters at Kent State University, killing four, wounding 11.

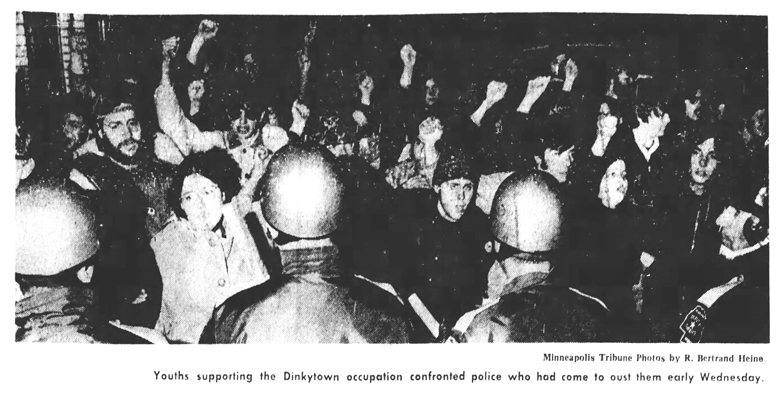

Press accounts of May 6 describe a 45-minute operation, beginning with a lone helicopter overhead. More than 100 police officers and sheriff’s deputies arrived, taking positions on the street with nightsticks and on roofs with guns. At this point in the story, Milgrom’s film changes from faded Technicolor to eerie, nighttime footage in black and white, showing protesters being dragged from the building. They quickly controlled three storefronts, as some protestors barricaded themselves in a fourth and others marched on the sidewalk singing “We Shall Not Be Moved.”

Deputies and demonstrators scuffled, a plate-glass window was smashed, and three men and a woman were arrested. Moments later deputies, using riot batons as battering rams, tried to break into the fourth storefront. Robert McLane, chief deputy sheriff on the scene, emerged from the barricaded doorway with Pence, who briefly stated the goals of the occupation then re-entered the room, followed by McLane.

Shortly, McLane again emerged, saying, “All right, let’s move in there and remove ’em.” Some demonstrators walked out; others were carried, struggling; most, however, were dragged by their armpits across the sidewalk, through broken glass, over the street and into paddy wagons. Officers warn the crowd to disperse, then five minutes later, begin a quick, easterly sweep, shoving and clubbing students. “Those struck also included a grey-haired man, a newspaper editor and a woman reporter, who was knocked sprawling to the ground, her glasses flying in one direction and her shoes in another,” the Minneapolis Star reported.

Former resident Lassman remembers it this way: “We were sound asleep and received a phone call from our alderman, who said they were going to close down the protesters tonight. So, we had a phone tree set up, and when we got the call, we called two other people and they called others.”

Lassman said she witnessed the raid from across the street, inside the Varsity Theatre. “People were on the roof with shotguns. I’m shocked, seeing all of these young people in the street … and here are 75-, 80-year-old people holding candles. … The good news is nobody was seriously hurt, to my knowledge.”

Lassman said that night a helicopter followed her home.

Fewer than 10 minutes after the streets were cleared, bulldozers began attacking the row of buildings. And by 4:45 a.m., the buildings had been reduced to broken wood and concrete, the helicopter still circling above.

But the Red Barn saga was far from over.

About two-and-a-half hours later, at the Red Barn on the other side of campus at 313 Oak St. SE (now home to the Lotus restaurant), a car smashed into the front window and came to a halt in the eating area of the establishment. Although the driver claimed to have swerved to avoid a pedestrian, news reports said no skid marks were found, and the pedestrian was a friend of the driver. [John F. Teeter, 20, was convicted of aggravated criminal damage to property.]

Also before the morning was over, five windows at another Red Barn on Lake Street were smashed.

Meanwhile, 38 Dinkytown protesters were hauled away in paddy wagons, booked and jailed, and after an appearance in Hennepin County Municipal Court, were released on their own recognizance. In addition, two 15-year-old boys were arrested and turned over to juvenile authorities.

The next day, May 7, 1970, 28 more people were arrested at the Stadium Village location for unlawful assembly.

The same day, Southeast residents filed a lawsuit charging that the restaurant would conflict with the plan for neighborhood development adopted by the Minneapolis Planning Commission in 1964. The suit said the Red Barn would be a drive-in restaurant and interfere with traffic; it also asserted that the wrecking permit that authorized razing the old buildings on the site May 6 was invalid.

For months to come, the court proceedings against the Dinkytown and Stadium Village protesters made headlines.

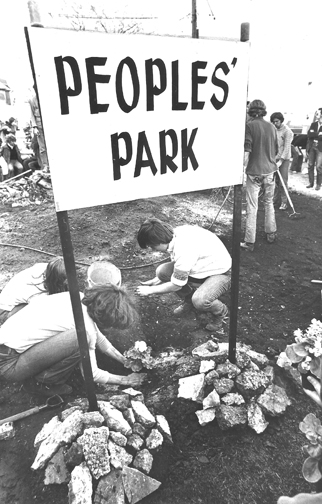

But perhaps more crucial than the initial protest–which began in the streets and now filled courtrooms–was what was happening at the Dinkytown site following the demolition. Well-documented in Milgrom’s film is the establishment of a “People’s Park,” a ragtag yet substantial array of gardens and playground equipment, a new phase of protest against the Red Barn project.

Although the lawsuit was dismissed in Hennepin Country District Court in July, it fueled the resistance to the restaurant, and by the following spring, two other businesses–Lancer’s clothing store and Team Electronics–were being planned for the site.

Finally, on Aug. 13, 1971, Red Barn announced the lease the company had for the property in Dinkytown had “already been transferred. … We felt it was fruitless to proceed against that kind of public feeling.”

Peaking in the early 1970s with more than 400 outlets nationally, Red Barn then struggled for many years and filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in New York in 1986.

According to a 1987 article in Nation’s Restaurant News, the bankruptcy protection came after a “health food concept called Lite Stuff failed to improve declining sales.” Emerging from Chapter 11 in 1987, Red Barn was negotiating to open Chicken Pantry Kiosks in a 61-unit convenience store chain based in Rochester, N.Y.

Nowadays 1307-1311 Fourth St. SE is occupied by Know Name Records, Magus Books, and–with the American flag flapping in front–a U.S. Post Office branch.

What was this protest about, then?

It certainly was, in part, about the intrusion of unsightly architecture–what one local newspaper columnist later called a “gustatory and aesthetic nightmare.”

It’s not incidental that “junk food” restaurants seemed to be popping up on every corner. The fast food industry (called “quick-service” then) was only an $8 billion industry in 1970. In 2002, total national spending on fast food hit $150 billion.

A flyer entitled, “The Dinkytown Occupation: A Statement of Purpose,” answered the question this way: “What is happening in five small storefronts in a neighborhood called Dinkytown is part of a larger movement among American city dwellers. … Dinkytown has been commercialized by domestic imperialism a la Burger King, McDonalds … and now, Red Barn. … What then is the real issue, and equally important, what is the real alternative? The issue is to see the difference between merely stopping pollution and actually asserting real control over our environment. The real issue is to understand that unless we control what our land is used for, we will have no control over what our lives shall become. A shoe repair shop, a coffee-house and an organic foods center will allow us to walk, converse, rest and eat in a better fashion. A Red Barn will make us run, chat, and gobble it down so we’re not late for class or an evening of T.V. Our environment makes us what we are. We must make our environment what we wish to become.”

More likely though, the Red Barn maelstrom was a spillover from the Vietnam conflict.

“I think some of the student energies slid across from anti-war to antibusiness,” Southeast resident Ron McCoy recalled recently. (McCoy was involved with the Strike Film Co-op, a loosely organized group of students filming antiwar activities.) “I think [the Red Barn protest] was a local focus on a national situation. We had no real outlet to express our frustrations, symbolic or otherwise.

“Coffman Union was a focal point for [war] protests, speeches, along with rallies,” McCoy said. “I remember running over to Coffman and getting folks to come over for the sit-ins in Dinkytown. More bodies were needed through the night.”

Filmmaker Milgrom adds, “It’s the Vietnam conflict that made the Red Barn [controversy], … the confluence of Vietnam and the conflict against corporate America and fast food. And the multinational incursion represented by McDonalds.”

Perhaps the real protagonist in the Red Barn story is Dinkytown itself.

“Dinkytown is a kind of repository, with a rich collection of oddball characters, artists, literary people, university students,” said Milgrom. “Somewhere in this transition of people through the years, there’s a permanence here. And that’s partly what our project is about. Everyone who comes to Dinkytown leaves with stories of their own. But many people come and go without knowing all the other stories and history.”

More photos: