Although today’s audience associates the phenomenon of dance marathons to the depiction in the film “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?,” there is a bit more to the story. (Stay tuned, as this page will exponentially expand soon!)

ALMA CUMMINGS

Dance marathons are said to have begun in America in 1923 when Alma Cummings, age 32, danced for 27 hours (March 30-31) with six different partners, beating a previous British record. This feat occurred at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City, and inspired others to break Alma’s record, and dance studios around the country started staging such events.

Alma Cummings – Getty Images

1928

On June 10, 1928, theatrical promoter Milton Crandall staged “The Dance Derby of the Century” at Madison Square Garden in New York City that set the standard for many others. The event ran until 2 pm on June 20 when the health commissioner shut it down. $5,000 was divided among the final eight couples. This event was followed by many others around the country, which featured room for an audience, a series of live orchestras, contests, and rules that regulated rest periods, partner changes, and whether or not the participants actually had to “dance” or just keep moving.

In Minneapolis, an “Endurance Dance” was put on by the Rainbow Division, Veterans Association, Minneapolis Chapter, at the Kenwood Armory, starting on Monday, June 18, 1928. This was probably the armory on The Parade that was demolished in 1934? Spokesman Frank McCormick, Jr., explained, “It is not a case of who is the best dancer, but which couple can dance the greatest number of hours.” Marathons were being held in Chicago, New York, and Pittsburgh, with the record up to 144 hours and 32 minutes. “Dancers go into the contest wearing overalls, knickers, soft-collard shirts, or bandanna neckwear – whatever is most comfortable is the rule, and some even wear bathing suits. No fancy steps are called for, nor is the race to the swiftest,” reported the Hennepin County Enterprise. McCormick explained, “Keep your shirt on, or in other words be calm, cool and slow, if you want to win a dance contest that counts its winners by the hours they can stand up and keep going, even though they inch forward like snails.”

The Bear Cat Dance Marathon took place at the Kenwood Armory starting on September 5, 1928, apparently going on for 104 hours with the help of Hopkins resident Jimmy Manchester, who entertained for eight hours each day.

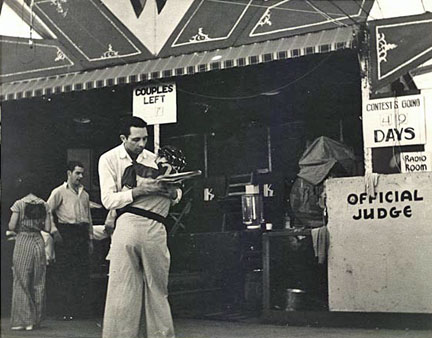

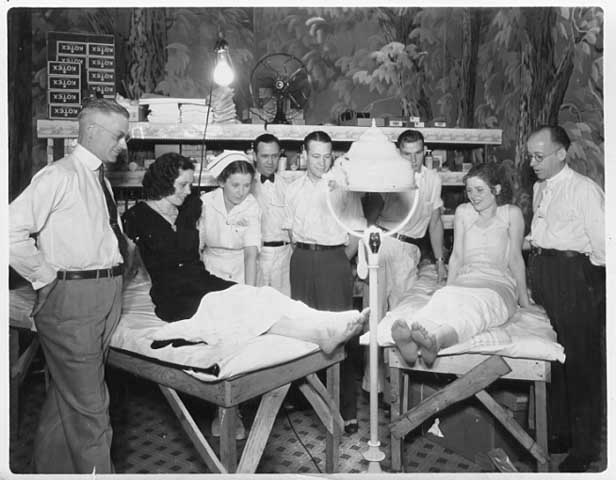

An All-Minnesota Dance Marathon was held in 1928 at the Coliseum Ballroom. Assuming this is the one in St. Paul, given the bandstand’s “WE” that probably stood for Wally Erickson, the St. Paul Coliseum’s house bandleader. Below are photos of the event from the Minnesota Historical Society:

During the Depression, dance marathons broke up the boredom of unemployed spectators and provided a source of income to those with the fortitude to participate. Many participants traveled from town to town with organized shows. Some sought the cash prizes, while others thought they might lead to movie contracts. June Havoc and Red Skelton were marathon dancers who became movie stars.

CALLUM DEVILLIER

Callum Leroy deVillier set the world’s record for marathon dancing. Incredibly, he danced for five months, from December 28, 1932, to June 3, 1933: 3,780 hours or 157 days. During his marathon career deVillier entered and won 12 events. When the movie “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?” came out, the record was attributed to others, but he set the record straight and won the respect of the folks at Guiness Book of World Records. deVillier was born on January 19, 1907, in Pilot Mound, Minnesota. His wives were Veronica Kuchinski and Helen Steinbach. He died in June 1973 and is buried in Lakewood Cemetery.

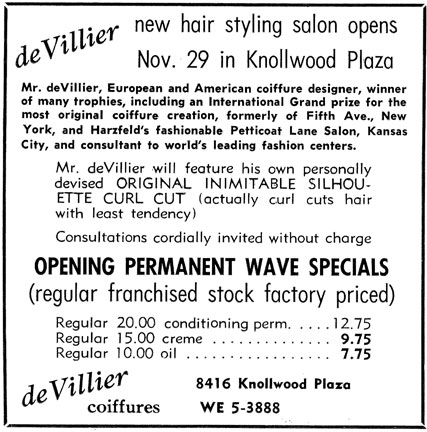

Curiously, deVillier became a hairdresser and worked at Knollwood Plaza in St. Louis Park. The ad below is from the St. Louis Park High School Echo newspaper, 1957:

WALKATHONS

By the 1930s the dance marathons seemed to have given way to “Walkathons,” where the participants merely walked around a track (although dance marathons may have remained popular on the coasts). There were several in the Twin Cities.

MINNEAPOLIS AUDITORIUM, 1932

NEW BRIGHTON

GOLDEN VALLEY

CRYSTAL

ST. LOUIS PARK

In 1934 a company set up a large tent (at one point referred to as the Wigwam), at 5501 Wayzata Blvd. It is unclear which side of Wayzata Blvd. this was on, but it may have been where the Doubletree Hotel is now. The St. Louis Park Historical Society has two pictures of this event, one showing five seriously fatigued couples, and one of a double wedding party posing in the tent. The latter, below, shows that there were 18 couples left, and that they had completed 598 hours.

Photo Courtesy Earl Ames

And there is a newspaper article (probably from the Hennepin County Review or Enterprise) that should be quoted in full:

WALKATHON HIT BY GRAND JURY

Retiring Body Says “Cheap, Contemptible Spectacle” Should Be Stopped

Denouncing the walkathon now in the last stages in a huge tent on Wayzata boulevard as a “cheap, contemptible spectacle,” the retiring grand jury Saturday called for a legislative act prohibiting similar contests.

Laws now on the statute books governing itinerant carnivals should be invoked to stop the walkathon on the grounds that it is injurious to the health of participants and detrimental to public morals, the report held.

The next legislature should pass an act specifically prohibiting “any such ridiculous endurance contexts being established anywhere in the state.”

In addition to the walkathon now nearing its close in St. Louis Park, another similar contest is being held near Shakopee, while several others are attracting crowds at other points in the state.

ST. PAUL

The photo below is identified as a Dance Marathon at University and Lexington in St. Paul, 1935

Minnesota Historical Society

RAY C. ALVIS

This photo is identified only as the Ray C. Alvis Walkathon in Minneapolis, 1934-1935. Research to follow!

Minnesota Historical Society

DEMISE OF THE MARATHONS

Dance marathons and Walkathons became a thing of the past as the Depression waned. There were several reasons:

- Community outcry about the inhumanity of the events

- Passing of the fad

- Unwillingness of police to monitor the 24/7 event

- Protests by local entertainment providers (e.g. movie theaters) to the competition

- Gearing up for World War II brought increased employment