Bruce Dybvig

Bruce Herbert Dybvig was a young Big Band musician and leader of some consequence in the 1940s and ’50s in the Twin Cities.

He was born on August 27, 1928, in Iowa. In 1940 he was living in St. James, Minnesota.

His musical story is told well by Leigh Kamman in a September 1950 issue of St. Paul Musician, the newsletter of the St. Paul Musician’s Union.

1946

SHUFFLETOWN BAND

It all began back in January 1946. Bruce, then a student at Minneapolis Central High School, organized the younger musicians of eight Minneapolis high schools. With fervor and a load of ideals they set books imitative of the Kenton, Rayburn, and Herman styles flourishing at that time. Most of the arrangements were scored by a young tenor man, Frank Lewis. Bruce, 17, and a high school senior, booked his 16-piece powerhouse on weekends at Shuffletown, a local community center.

The band was referred to in the local press as the Shuffletown band, after the place they performed every Friday night for two years. Dybvig had a day job driving a bakery truck. Shuffletown was apparently both a place and an organization, sponsored by the Loring Park Community Council, and made up of 600 members.

The photo below showed part of the then 16-member band holding a jam session. Pictured are Dybvig, Jack Cottrell, Jack Coan, Bob O’Connell, and Jack Wellnitz, with Paul Kaatrud at the piano and Tinkie Ross, chantuse, perched atop the piano.

LOOK AMATEUR SWING BAND CONTEST

In April 1946, Look Magazine decided to run a national contest to find up and coming young musicians. Dybvig and his orchestra decided to enter.

Kamman:

Bruce, who is a rather long-ranged planner, for young men, was asked how he happened to enter the contest. “I didn’t happen to enter the contest,” he replied. “It seemed like a good thing. Everyone liked the band at Shuffletown back home. We were cocky kids, and we wanted to see how we stacked up against bands from other areas, so here we are.” Bruce, in short, never happens to do anything.

The Regional contest took place in Chicago on June 30, 1946, and involved 40 bands from 10 states. To get there, the 20 members of the band:

scraped up a flivver, “touched” their parents and rode or hitch-hiked to Chicago… They were given free lodging in a Chicago hotel – in rooms without bed linen because of some interruption of service. (Minneapolis Star, August 15, 1946)

ON TO NEW YORK

The Finals were to be held on August 24, 1946, at Carnegie Hall in New York City, but the problem was how to transport 20 teenagers and a chaperone with limited funds. Chicago was one thing, but New York was something else. The contest would pay for 17 musicians, but the kids of Shuffletown were going to have to come up with the rest by raising the cost of dances. But then polio began cutting attendance.

Dances were held to raise revenue; one on August 2, 1946, for the uniforms and arrangements, and a last-ditch fundraiser for the musicians and extra chaperone on August 16. Fortunately, 250 of the 600 members of Shuffletown came out and the coffers were filled. The “Shuffletown Band” could ride the train in first class accommodations to New York.

Kamman:

In New York, finally, his big 20-piece band came through. Against young music makers from Los Angeles, Kansas City, and New York, the Dybvig crew walked off with the big band award at Carnegie Hall. And instrumental in their winning was arranger Frank Lewis, who gave the band its style in the timely sound of big names of the day.

The band’s triumph was reported in the November 12, 1946, issue of Look:

This 16-piece band [actually 20] came out of the Midwest to win the national award. It is an All-Minneapolis outfit, recruited from eight local high schools. In June the band traveled by day coach and jalopy [without brakes] to Chicago where it won the regional finals. Then, sponsored by the Loring Park Community Council, the musicians traveled first class [by train] to the New York finals. … Look’s nationwide amateur swing band contest has given these award winners and scores of other outstanding young musicians a boost toward the opportunities in the field of music that they have long dreamed about.

The orchestra played:

- “Blue Lou”

- “I Cover the Waterfront”

- “Mandy”

Members of the band were:

- Leader: Bruce Dybvig (also best alto sax – an article said that Dybvig had only been playing sax for two years.)

- Arranger: Frank Lewis

- Trumpets: Jack Coan, Dick Zemlin (and special award), Jerry Strauss, Phil Liniwic, Don Specht

- Saxes: Bruce Dybvig, Frank Lewis, Robert O’Connell, Donald Narveson, Jack Wellnitz, Wayne Herold

- Vocal: Tinkie Ross

- Trombones: Stan Haugesag (also special award), Duane Solem, John Roth, Darrell Barnett

- String Bass: Paul Sanders

- Piano: Paul Kaatrud (also best piano)

- Drums: Jack Cottrell

- French Horn: John Kohler

The Afro-American newspaper also reported that on August 24, 1946, “the two Kings of the trumpet, Cootie Williams and Erskine Hawkins,” held a jam session at Carnegie Hall “that will never be forgotten in the annals of jazz.” The session was to “pay tribute to the amateur swingsters” unearthed by the contest. Every band leader who was in and around New York showed up for the event, and proceeds from the jam-packed event went to the Boys’ Club of New York. At the end of the evening, the wives of the esteemed trumpeters presented gold statuettes to be given to the outstanding trumpet players who had been “unearthed” by the contest. (August 31, 1946)

An interesting note is that an 18-year-old Sam Butera, a contestant from another band, won the award for Best All-America Instrumentalist. Butera went on to have a successful career playing tenor sax with his band the Witnesses.

HOME TO MINNEAPOLIS

The band arrived home as heroes, greeted by Mayor Hubert Humphrey and other Civic leaders.

Back to Kamman’s narrative, written in 1950:

Dybvig and men returned to the Twin Cities for two years’ worth of one-nighters at colleges, high schools, civic events, and sales promotions. The important fact was that the band was working, learning, and doing a little over-achieving, which in the light of experience, isn’t as negative as were the sneers and snide remarks of other local music makers. The band was playing some difficult and intricate modern scores the snide characters could and would not cut.

The photo below isn’t very good, but it shows the orchestra at its peak strength of 22 members.

In the photo below, Dybvig poses with the trophy and his new vocalist, Shirlie Larson, who replaced Tinkie Ross. The caption indicated that the band was made up of 22 members and would make its first public appearance at a dance for the West Lake Veterans Association at the Minneapolis Armory on November 2, 1946.

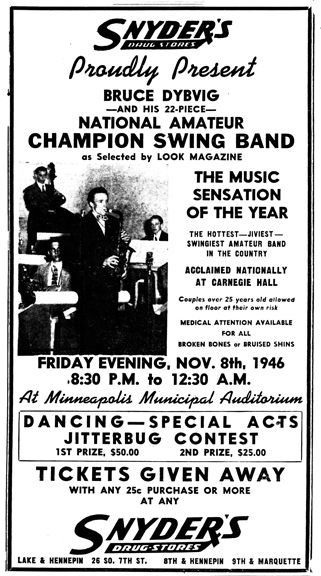

SNYDER’S DANCE JAMBOREE

Snyder’s Drug Stores sponsored a huge dance at the Minneapolis Auditorium on November 8, 1946, complete with an on-site medical team for all “broken bones and bruised shins.” Dybvig’s orchestra numbered 22 members. There was a jitterbug contest during intermission, with Miss Lillian Vail, Mr. David La Vay, and Miss Dorothy Lundstrom as judges. LaVay, at least, was a dance teacher. The Master of Ceremonies was Impersonator Joe Jung. The show was to be broadcast over WTCN between 11 and 12 pm.

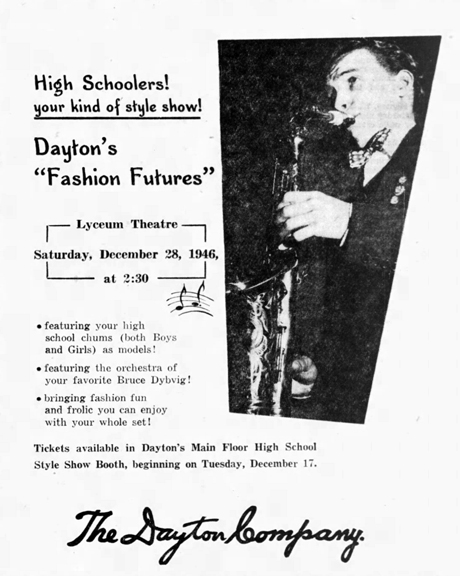

The ad below shows Dybvig’s orchestra accompanying a Dayton’s fashion show at the Lyceum Theater on Saturday, December 28, 1946.

Dybvig’s 22-piece orchestra was back at the Minneapolis Armory for a New Year’s Eve dance for the West Lake Veterans Association on December 31, 1946.

1947

On February 15, 1947, the band performed for the Congressional Ball at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota.

In the Spring of 1947, the band provided the music for the Junior Class Prom at the University of Minnesota.

On July 25, 1947, Dybvig’s band was hired to play for the Aqua-Teen-Twirl, a dance for teens at the Minneapolis Auditorium with two other bands directed by Jerry Dibble and Bud Strawn.

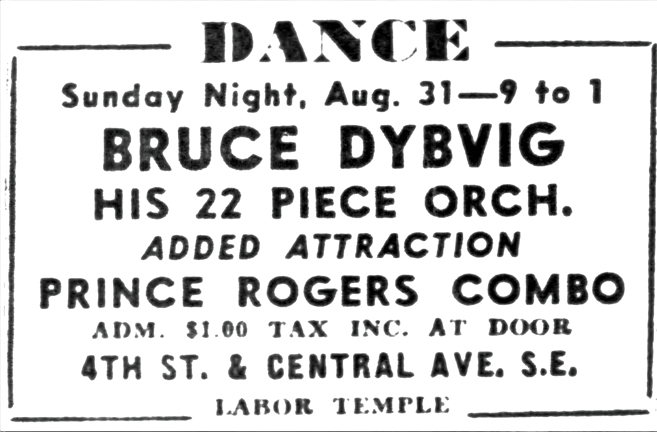

In the days when the Labor Temple was a hotbed of Big Band, Jazz, and Rhythm & Blues music, Dybvig was there at least once, sharing the bill with none other than the Prince Rogers Combo, father of Prince.

Kamman:

Another milestone in the cycle of seasoning was a “We Call It Jazz” concert. A local disc jockey and a brother-in-law of Eddy Condon, co-sponsors of the affair, invited Bruce to play a concert for modern big bands in December of 1947. Bruce brought 5 brass, 4 trombones, 1 French horn, 6 reeds, and 4 rhythms to that December 14, 1947, session. 20 men honked and blasted in dissonant registers to the one thousand people crowded in the Radisson Hotel ballroom. Dybvig and men almost out-Rayburned Rayburn that night. The audience was impressed, impressed with initiative and youth and there was the feeling that with those qualities the refreshing, the new, and the thrilling, were also there.

1948

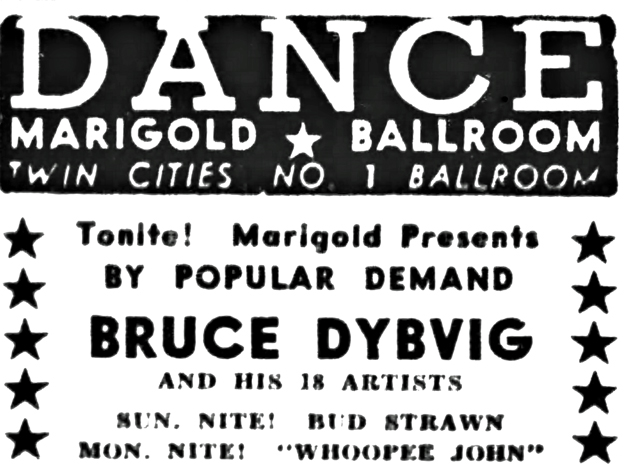

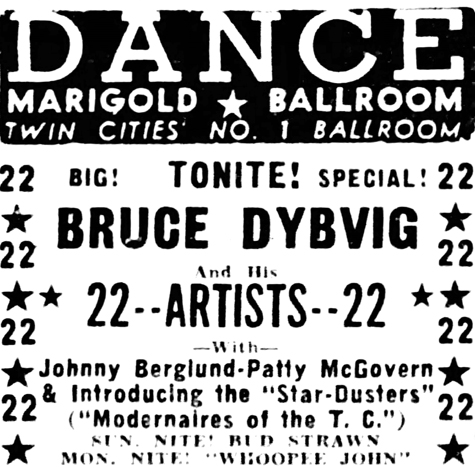

Two engagements at the Marigold Ballroom were found, but with 22 musicians, the fee probably couldn’t pay everyone enough to be worth it.

Kamman:

Still another cycle in the development of the Look All Americans was a meeting with Johnny Bothwell. The meeting resulted in a partnership between Dybvig and Bothwell. An Eastern tour followed which ended abruptly about two months later in August of 1948. The same thing happened to this Bothwell venture that has happened to every other Bothwell venture – that ultimately has resulted in Bothwell’s “unwilling retirement.” But in spite of the breakup, which almost cost Bruce his health, there were positive effects. It made men of his 20-year-olds. Experience, big name musical direction under Bothwell’s influence, playing constantly the combined Dybvig-Bothwell book, and living on the road knocked out that starry-eyed look.

Then 19, Dybvig returned home and retired to seclusion for 30 days to eat, sleep, and think things over. At the end of the retreat, rested and bolstered by an evaluation of the Bothwell experience, he began a long haul up and out of debt. He reorganized the band with practically the same personnel and began putting out a brand of music that startled local dance fans. Many a couple did a double take to see if Dybvig or Bothwell were making with the music.

1949

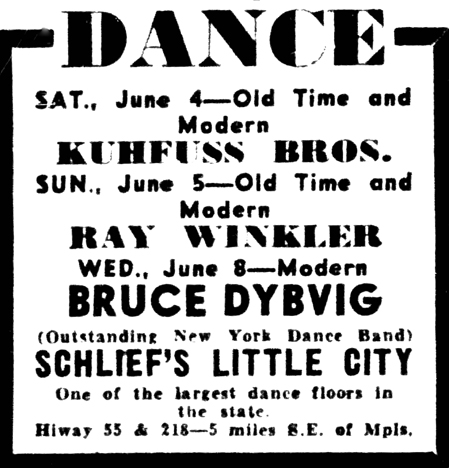

Is the ad below for an appearance at Schlief’s Little City on June 8, 1949, implying that Dybvig’s band is from New York?

Kamman:

In the summer season of 1949, the band jumped northward to Winnipeg Beach, Manitoba. Result was a season of American jazz and dance music for some very happy Canadians.

Following his return to the Twin Cities in the fall of 1949, the band began another season of filling dance calendars with his 16 and 20-piece operation. The business of budgets and sizes of bands began to raise its ugly heads, and Bruce began to change his thinking about the business once again. Faced with a book for 16, 20, and 22 men, Bruce with aid of local arrangers Pops Wakefield, Derk Fisher, and Jack Nowicki built a 7-piece unit geared to fit into his big band.

Trumpet, brass trumpet, alto, baritone, piano, bass, and drums have been blended into one of the most flexible groups heard in these parts. The sound is big with rich effects carried by the baritone.

Bass trumpet, alto voiced with the baritone, give still greater depth. The unit is versatile. The job best demonstrates a new versatility. For sake of trend, it’s Dixie, Yank Lawson style on one side, waltzes with a full non-tenor melody next, and ballads with rich, soft backgrounds and occasional sleepy alto reminiscent of the Bothwell era. Bruce has his earnest young moderns playing commercial, and the experiment seems to please the dancers and fans alike, because the band has a style all its own.

All these current and timely sounds emanate from Bar Harbor where Bruce Dybvig is building a new reputation and cycle of experience. It’s a new step in the right direction for a persevering and mature young man of music, for now at 21, with five years of band leading under his saxophone, he combines musical skill with big name experience, and a wise insight into the financial affairs of the business plus a basic music business philosophy. From here Dybvig looks like one of the names of tomorrow, and name someone will latch onto.

1950

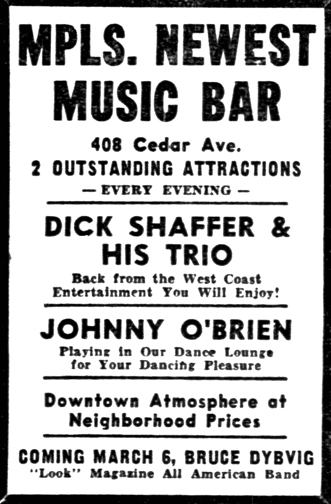

On March 6, 1950, the Dybvig band performed at the Music Bar at 408 Cedar Ave.

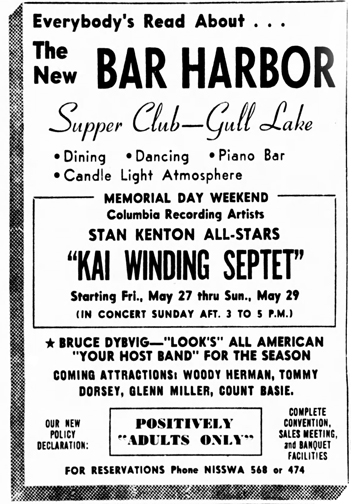

Dybvig had an 8-piece band working at the Bar Harbor resort near Brainerd during the summer of 1950. The ad below for May 6, 1950, boasts that Dybvig has performed at the Symphony Ballrooms in Chicago and Boston. He would work at the Bar Harbor or Breezy Point resorts until about 1963.

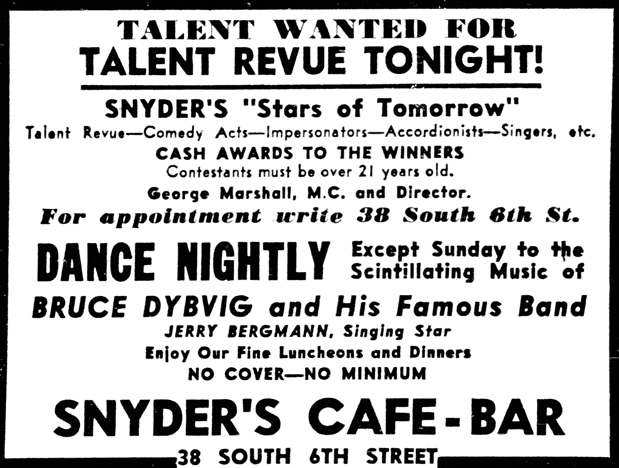

After Bar Harbor came a stint at Snyder’s Cafe, in September 1950.

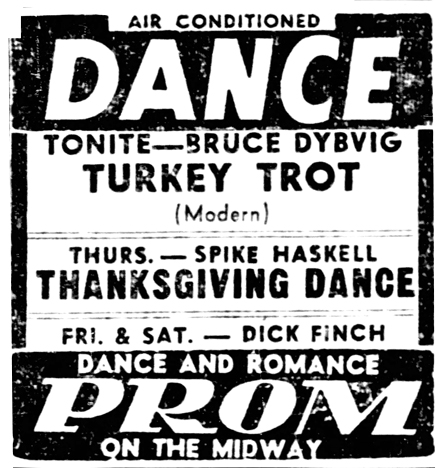

Thanksgiving time 1950 saw Dybvig at the Prom Ballroom.

1951

Dybvig’s band was still popular, as evidenced by the fact that the Edina-Morningside High School Class of 1951 specifically requested that they play for their graduation dance.

1952

In January 1952 the Minneapolis Flame began to program jazz on Sunday nights, a show called “Jazz Carousel” produced by Dybvig. Both Dixieland (Harry Blons) and modern (Percy Hughes) jazz was presented. Dybvig’s show was described as “His Ultra-Modern Music” in 1952. In 1952 he also performed at the Point.

In a conversation with columnist George Grimm, Dybvig explained that teenagers no longer wanted the “firehouse style of fast, loud, jump music.” Now they want six slow numbers to one fast one. Or they want the “Businessmen’s Bounce: a hotel style two-beat where you dance on every second beat.” (Minneapolis Tribune, January 3, 1952)

In the spring of 1952, Dybvig’s band provided the music for Blake School’s end of school dance for the senior class at the Woodhill Country Club.

1953

In 1953, Dybvig introduced his 8-member Royalaires at the House of Hastings and the Point in Golden Valley.

Starting December 14, 1953, Augie’s Theatre Lounge featured Bruce Dybvig and his trio. Members included Elaine Bravis on bass, and Rufus Webster on piano. Sally Saylin, who had sung and played piano in the lounge at Augie’s since 1946, was held over in the piano bar. (Minneapolis Tribune, December 13, 1953)

1954

On July 20, 1954, Dybvig’s Royalaires played the Aqua Canopy show on top of the L.S. Donaldson Co. Canopy between Sixth and Seventh Streets on Nicollet Ave.

In 1954, Will Jones called the Royalaires, performing at the Point in Golden Valley, the “brightest bunch of show-offs around these nights:”

Sometimes It’s a vocal group with five voices and rhythm accompaniment. Sometimes it’s an instrumental group. With a bongo drummer added, it’s a Latin band. And they’re mostly all capable soloists.

Sample versatility: Frank Lewis, the arranger, also sings, also plays bass, and also plays tenor sax. (Minneapolis Tribune, August 25, 1954)

In November 1954, Dybvig was sentenced to 30 days in the workhouse for driving after his license was suspended. (Minneapolis Tribune, November 4, 1954)

1955

On April 16, 1955, Dybvig’s 10-piece band was chosen to play at a sock hop when the City of Richfield celebrated its receipt of its All-America city award. The dance was held in the new Richfield high school’s gymnasium. Six or seven original members of the 1946 band were expected to be hand. A highlight of the dance was the judging of the Richfield entry in the 1955 Miss Minnesota contest. (Minneapolis Star, March 3, 1955)

In October 1955, Dybvig was expelled from membership in the Minneapolis Musicians’ Union Local 73. The union said that the expulsion had to do with failure to pay union members hired for work in orchestras. On July 18, 1958, Dybvig filed suit against the union, charging that he was “maliciously blackballed without just cause,” and demanded $30,000 for “great embarrassment, humiliation and emotional anguish and physical ills;” $200,000 in punitive damages; and return of $400 which he said he had been require to post with the union to pay any claims that the union had against him. (Minneapolis Star, July 18, 1958)

1956

On August 12, 1956, Will Jones of the Minneapolis Tribune wrote a long story with the unfortunate titles, “Death of a Band: Triumph to Defeat in 10 Years” and “‘Band of Tomorrow’ is Forgotten Today.” The article spoke of a final 10-year reunion of the original band members and gave updates of each. Even that event resulted in a loss of $1500. Some highlights of that article:

- In the last ten years Dybvig figured he had worked 1,200 engagements and grossed $125,000, ending up with an average hourly wage of $1.25.

- He had trouble getting work in Minneapolis, so he had to dream up a job for himself, publishing a directory of talent and entertainment services for the area. An article from 1958 show that he was listed as president of Talent Directory, Inc.

- He should have known that Big Bands died in 1946 and it was pointless to try to keep his going.

- Dybvig said that the representative from Look lost interest and failed to deliver on promises of hotel and movie contracts.

- Bruce always wore his hair long, despite taunts similar to rock ‘n’ roll musicians a decade later. He finally got a crew cut when he took up water skiing and his hair got in his eyes.

1956 was another bad year for Dybvig; his wife Inez divorced him for “Cruel and inhuman treatment” (in those days you had to have a reason). They had married in 1947 and had two children. Bruce blamed the breakup on the long and unusual hours of a musician. (Minneapolis Tribune, June 9, 1956)

1958

In 1958, Dybvig sued the Minneapolis musicians’ union for expelling him in 1955. See 1955 above.

1960

Dybvig’s was the house band for the summer of 1960 at the Bar Harbor Resort in Northern Minnesota.

1964

By 1964 only two of the original 20 members were working professional musicians.

1965

In 1965, Dybvig “allowed himself to be arrested rather than pay 55 cents to an argumentative taxi driver who didn’t want to wait outside a downtown restaurant while Dybvig got a takeout order of Spaghetti.” (Minneapolis Star, June 19, 1975)

1970

In 1970 he was arrested for writing a bad check and spent 106 days in the Hennepin County jail after refusing to post a $100 bond while awaiting trial. He was released on his own recognizance in March 1970. “He was convicted of forgery and placed on probation for two years. He had not ingratiated himself with courthouse employees. A condition of his probation was that he not ‘loiter’ in the building.” (Minneapolis Star, June 19, 1975)

1971

In 1971 Dybvig said that prisoners in the jail were frequently mistreated, a charge that Sheriff Don Omodt said were “totally unfounded.” Nevertheless, the board of directors of the Urban Coalition of Minneapolis voted to investigate conditions. (Minneapolis Tribune, August 6, 1971)

1975

Dybvig shows up in the news again in June 1975 as a frequent observer in Hennepin County District Court, as described in an article about court watchers by John Carman in the Minneapolis Star on June 19.