Olson Memorial Highway/Sixth Ave. North

Much of the following information comes from a Ph.D. thesis presented in May 1964 by U of M graduate student Robert A. Stebbins entitled The Jazz Community: The Sociology of a Musical Sub-Culture.

Also see:

A History Of North Minneapolis: Sumner Field

SIXTH AVE. NO.

Sixth Ave. No. was a commercial street in one of two predominantly black areas of Minneapolis. The site had once been the Oak Lake Addition, the finest section of the city in the 1890s. Most of the buildings on the 700 block (at Lyndale) were built in the 1880s and ’90s. They were most likely either built as houses and became apartments and stores or were built as apartments and stores to begin with.

By 1900 Jewish immigrants began to settle in the area and the wealthy residents began to leave.

The start of World War I saw a migration of blacks to Minneapolis, and by 1920 Oak Lake was almost entirely black. The old established white families had moved farther south along Lyndale Avenue and the Jewish community had moved farther west along 6th Avenue No. and Plymouth Avenue. A commercial strip developed along 6th Ave. with stores, offices, machine shops, etc.

Clarence William Miller reminisced about the heyday of the Avenue in the 1920s. He described two men’s “social clubs:”

- The Four Leaf Clover Club was made up of men who “made their income from the earnings of their women.” They gave Holiday Breakfast Balls, at the Southside Auditorium, which lasted from midnight to 5:00 am. Eli Rice’s orchestra played for all of these affairs.

- The Wolverine Club, of which Mr. Miller was the sole survivor as he wrote his memoirs, hosted dances in the hall over the Nankin Restaurant.

Also in the 1920s it was said that Kid Cann had a headquarters on the south side of Sixth Ave. between Colfax and Dupont.

Photo from the old days courtesy Minneapolis Collection, Hennepin County Library

OLSON MEMORIAL HIGHWAY

In 1933 construction was authorized for Highway 55. Upon Governor Floyd B. Olson’s death in June 1936, the Minneapolis City Council renamed the stretch of road between Lyndale Ave. and the City Limits Olson Memorial Highway on September 10, 1937.

The following is an article in the Minneapolis Spokesman dated September 10, 1937:

Sixth Avenue North, that picturesque section of Minneapolis which has ranked in the minds of the well traveled as does Beale Street in Memphis, State Street in Chicago, Market Street in St. Louis and Lennox Avenue in New York, will soon lose its former identity if plans announced by a Minneapolis city council committee are carried out.

Friday the city council is expected to pass a law renaming the famous thoroughfare Floyd Olson Memorial Highway. That portion of the street from Seventh Street to the west city limits will be affected.

The most famous corner on Sixth Avenue North is the Lyndale Avenue corner where for years the colored people of that section have congregated making a street which was highly reminiscent of parts further south.

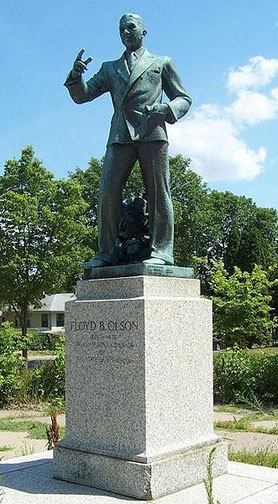

Statue of Floyd B. Olson, situated on south side of Highway 55.

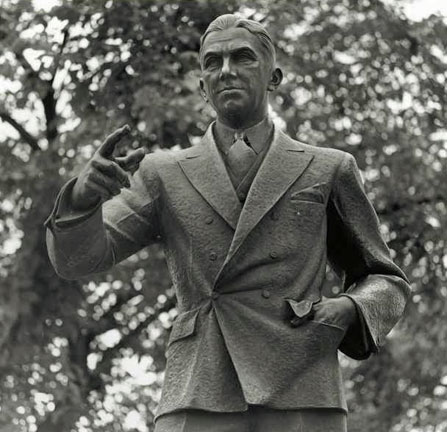

Black and white photo courtesy Will Lumpkins

By 1937 the area had become a slum, and one of only two places in the city where blacks were allowed to live. Even after restrictive covenants were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1948, de facto segregation existed for decades, forcing blacks of all classes to live in substandard housing. Oak Lake itself was filled in to provide room for the municipal market, completed in 1937.

Minnesota Historical Society

SUMNER FIELD

Buildings on the north/even side of Olson Memorial Highway were demolished in 1936 in order to build the Sumner Field Public Housing Project, the first such project in Minnesota. It consisted of 44 two-story row houses and four three-story apartment buildings in municipal park-like setting. It was a government effort to clear slums, address a housing shortage and create construction jobs during the Great Depression. Private landlords opposed it.

1940

The early residents of Sumner Field were predominately Jewish along with some African-Americans. It was originally racially segregated, and eventually became predominately African-American. In the 1970s it became home for a large population of Southeast Asian refugees. Sumner’s most famous residents were the musician Prince Rodger Nelson and Richard Green, who at one time led the Minneapolis and New York school systems.

Sumner Field was the oldest, largest and second of four housing complexes demolished under the settlement of a lawsuit (1995 Hollman settlement) alleging that public agencies discriminated by concentrating minorities in inner-city public housing. Sumner Field was razed in 1998. It was replaced by the Heritage Park Housing Development, built between 2002-2009. Heritage Park is roughly bounded by Lyndale, Emerson, Third and 10th Avenues North. It is a mixed income development that no longer concentrates minorities or the poor.

GLENWOOD REDEVELOPMENT

The remaining buildings on the south side continued to deteriorate;

Stebbins:

With the deterioration came vice and crime, with prostitution, gambling, and after-hours drinking commonplace. But it also provided the fertile ground from which Minneapolis’ most fully developed jazz community sprang.

In 1955 the Glenwood Redevelopment Project was undertaken by the City of Minneapolis, razing nearly all the buildings from the Harrison School to 7th Street No. and from Olson Memorial Highway to Glenwood Ave. With the demolition went the Oak Lake Addition and the numerous little bars, restaurants, after-hours joints, and the Olson Highway jazz community.

Stebbins mourned the loss of the old neighborhood:

… giant wrecking machines were battering into rubble many of the buildings from which the alternately gay and mournful strains of jam sessions had once filtered through decaying walls to drop like sleet into alleys, where once denizens of this midnight world had slouched half drunk and stolen a furtive look both ways before relieving themselves, half concealed, behind the ash cans. The bulldozers were sweeping the rubble rattle-trap rooming houses, dives and bistros, into piles which would later be loaded into dump trucks and hauled away.

Below: Architect Oskar Stonorov (left) and University of Minnesota architect professor Walter Vivrett look over a plan of the Glenwood redevelopment project of the area in 1957.

StarTribune photo.

Here is a Spreadsheet I started, taking info from the Minneapolis Spokesman and inspection permit cards at the Minneapolis Downtown Library’s Special Collections. Special Collections also has reverse directories, which I have not looked at… yet. This spreadsheet badly needs updating. The most interesting building has to be 718 Sixth Ave. No., which hosted such venues as the Cotton Club, Club Kongo and Club Morocco. It was the last building to fall.