Booker T Cafe

The Booker T Cafe, sometimes seen as the Booker T Tavern, was located at 381 Rondo Ave. at Western Ave. in St. Paul. There was also a second location in Downtown St. Paul. This is a difficult tale to tell, because there are actually four venues involved, several addresses, and the history is totally non-linear. I will do the best I can. I am deeply grateful to members of the Ellis family for their contributions to this page.

IMPORTANT NOTE

My sources for this page were the Minneapolis Star and Tribune, accessed online. The St. Paul Dispatch and Pioneer Press are not available online, and although they are available at the Minnesota Historical Society on microfilm, they are not searchable. I have also done a search through the St. Paul Recorder, a weekly newspaper for the black community.

Jeremiah Ellis, a descendant of Mance Ellis, has requested, and rightly so, that I include this paragraph that acknowledges the inherent racism of the mainstream press of the day:

This article is deeply limited by the inherent bias in the mid-century media reporting upon which it is based. The narrow reporting and narrative does not depict the fullness of African American individuals nor account for their broader impact in the African American community. Complicit in this biased worldview are the policy makers who, in their administration and regulation, prioritized land and property over Black livelihood and people.

381 RONDO

There are few resources available about St. Paul buildings. The Minneapolis papers reveal that:

- Bessie Pierce ran a tavern at 381 Rondo Street in July 1936.

- In February 1944, John C. McGee, Cafe owner, plead not guilty to the charge of selling liquor to an Indian woman.

- The building was a tavern in January 1945.

- It is unclear when the building at 381 Rondo Street became Booker T – a guess is between 1947 and 1950.

THE ELLIS FAMILY

The Booker T was owned by Mance Ellis, who was born in 1896 in Mexia, Texas.

Jeremiah Ellis:

When viewed through the national lens of the Great Migration, Mance Ellis was a migrant who sought greater opportunity for his family outside Jim Crow oppression of Texas. He journeyed with his wife, young children, his sister and his little brother the 1,100 miles from Texas, to Minnesota, seeking space to carve out a life for himself and his family and believing Minnesota would allow upward mobility. However pre-civil rights era Minnesota unraveled those aspirations. In 1945, 321 of the 601 Twin Cities employers who responded to a survey said they would not be willing to employ African Americans.

We do know that in 1940, and up to at least 1947, Mance Ellis owned his own business as a decorator on Rice Street and County Road D in St. Paul.

Kamuel Ellis Family:

Mance and his wife Mattie Ellis had four sons (Herman, Rudolph, Booker, and Kamuel) and two daughters (Ella Mae and Rosemary) who survived to adulthood. The property on Rice Street and County Road D in St. Paul was referred to as The Farm. Mattie Ellis was a Deaconess at St. James AME Church in St. Paul.

THE BOOKER T

Mance named the Booker T after his son, paying homage to Booker T. Ellis’ illustrious boxing career (26 wins [11 KOs], 21 losses [4 KOs], 4 ties) in the 1940s. Because of his boxing days, Booker T was a celebrity in the Rondo neighborhood. Also involved was Mance’s son Rudolph K. (Rudy) Ellis, who was born in 1924 in Minnesota.

Jeremiah Ellis:

From a Minnesota economic perspective, the Booker T was intended as a protective shield to counter oppression directed toward Minnesota Black men. For Mance’s sons Booker T. and Rudy, this protective shield was both an inheritance and a commitment to Minnesota.

The Kamuel Ellis Family:

The Booker T on Rondo, the second location in Downtown St. Paul, and other manifestations are part of the community and Ellis Family lore. The Booker T was a Barbeque Rib restaurant and grocery store for the Rondo community in St. Paul. Its history as a music venue is anecdotal and based on family stories of Jazz, including friendships with Dizzy Gillespie and Ella Fitzgerald. Music was part of this tavern, Barbeque Rib joint, bottle club, etc. – a speakeasy with food, et al after hours that spans from the late 1950s to the early 1960s in the Rondo community.

Phone book ad courtesy Jeremiah Ellis

THE BOOKER T AFTER HOURS

As noted above, after the grocery store and restaurant closed for the night, the Booker T became an after-hours club where drinks (or set-ups) were served, music was played, and people danced. It was located on Rondo Ave. in St. Paul, the hub of black commercial and social life in a segregated city where there were few choices for entertainment, no matter what your financial or social strata. Name entertainers would drop by after their shows Downtown and relax with the locals.

In January 1960, Mance reported that someone broke into his place at 381 Rondo and stole cigarettes, money, tubes and recording chassis from the juke box, a case of beer, and 25 barbequed ribs. The robber probably enjoyed the ribs the most; Mance Ellis was famous for his barbeque sauce and took the recipe to his grave.

June 9, 1960 photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

The building, along with most of the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul, was demolished for the construction of Interstate 94. The section between Minneapolis and St. Paul was completed in 1968.

BOOKER T CAFE NO. 2

A second Booker T Cafe shows up on or before July 1959, which either moved around a lot, or had a peripatetic address. In July 1959 it was described in the Recorder as 447 1/2 Broadway in a story about someone who took coins from a jukebox and 25 pounds of ribs. Turns out it was an inside job. The perpetrator admitted to taking the ribs but not the coins.

In September 1959, the Recorder gave the same cafe’s address as 579 1/2 Broadway. This comes from a report of a sting and arrest of a waiter for selling liquor without a license to a “Pretty N.Y. Policewoman.” The waiter got a sentence of $100 or 10 days. Mance Ellis, proprietor of the Booker T, was notified to report to the Morals Division Office.

St. Paul bootleggers are reportedly nervous and worried over the new departure of the St. Paul police in securing evidence. One “legger” said “the town’s getting hot, guess I’ll have to get me a job.” (St. Paul Recorder, September 25, 1959)

The next time we see the Booker T No. 2 is in November 1959, when Mance and an employee were having a go about wages she said she was due. The police were called, she had a go at them too, and off to jail she went. She was given a 15-day suspended sentence. The address of the Cafe was given as Grove and Broadway.

All of these addresses are gone, but as far as I can tell were in the same general location, in the northeast section of where Highways 94 and 35E come together.

THE RONDO IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION

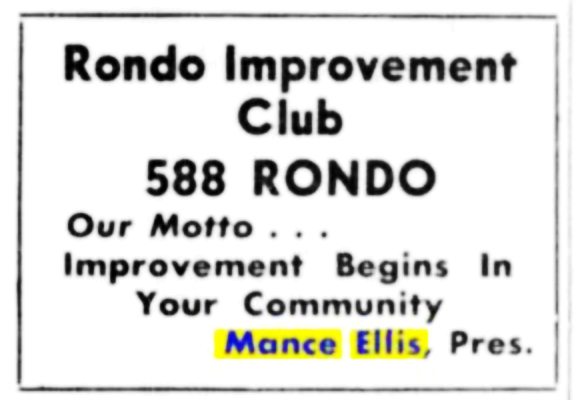

Mance Ellis was also the proprietor of the Rondo Improvement Association, 588 Rondo Ave. His partner was German Sperling, who owned the building. From about 1957 to 1959, the St. Paul Recorder published these ads weekly:

St. Paul Recorder, February 2, 1957

BOTTLE CLUBS

Although this organization appears to have been styled like a service club like the Rotary and the Kiwanis, it did fit the description of a “Bottle Club,” where members would bring alcohol and drink and (I hope) dance until the wee hours. Since they were not regulated, they stayed open whenever they wanted.

Bottle clubs became popular in the Rondo community because segregation made black people unwelcome in white clubs, and there were few opportunities for black entrepreneurs to start their own clubs. The clubs on Sixth Ave. North in Minneapolis had been removed and there were fewer and fewer places to go.

NORTH CENTRAL COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION LETTER

But the Rondo Improvement Club’s activities were not going unnoticed. These are excerpts from a letter sent on January 21, 1958, to the St. Paul Commissioner of Public Safety by an organization called the North Central Community Association:

We are writing you of our grave concern, relative to the appalling increase of disreputable clubs, and “after hour joints” operating illegally,, in the Rondo-St. Anthony area. The coming of the proposed Freeway through her and the scarcity of suitable sites has caused many of these clubs to seek to establish themselves in private homes and others to relocate deep into the residential area. The apparent big profit and freedom of operation seems to be the cause for the continued existence of most and an incentive for others to form. These clubs obviously are a public menace and a hot bed for crime and vice in the neighborhood.

We cannot over emphasize the fact that a petition is already on file against the club operating at 588 Rondo Ave. This club advertises in the paper for memberships and operates full-force illegally after legal establishments close. It is gaining a wide reputation as a good time wide open club which attracts many undesirables in the Twin Cities and the upper midwest. Vile and vulgar language is frequently used in the presence of passing school children.

Published in the St. Paul Recorder, January 31, 1958

THE TURTLE CLUB

The Turtle Club appears to have been the same kind of organization as the Rondo Improvement Club – references in the St. Paul Recorder show that it provided scholarships and prizes for different events in the community. The treasurer was Rudy Ellis, Mance Ellis’s son. Booker T. Ellis was the acting secretary of the Turtle Club at one point. The Club started with a membership of 400, and by 1958 it had grown to 1,000. The Turtle Club was also mentioned in the letter to the police of January 21, 1958, quoted above.

THE BOTTLE CLUB RAID

At 2:19 am on January 25, 1958, 211 people were arrested in raids of the Rondo Improvement Association and the Turtle Club – described as the biggest raids in St. Paul history. The City’s Chief of Police personally led the raids, along with 70 police officers. One description of the raid said that the customers just kept on dancing until they were rounded up – music!

Both Mance and Booker T. Ellis (and their partners) were released on $200 bail. They were also charged with disorderly conduct. (Minneapolis Star, January 25, 1958)

THE TURTLE CLUB REDUX

The January 1958 raid of the Rondo Improvement Association may have meant the end of that particular institution. Reading through the St. Paul Recorder, it seems clear that Mance Ellis was a prominent member of society and his church, and may not have wanted to associate himself with anything unsavory.

But the Turtle Club lived on, and would do, in theory, for six more years.

Searching for the Turtle Club found it at several addresses. The first address noted in January 1958 was Western and Rondo. An item from April 1959 about a shooting cited 395 Rondo. Another report said 354 Rondo.

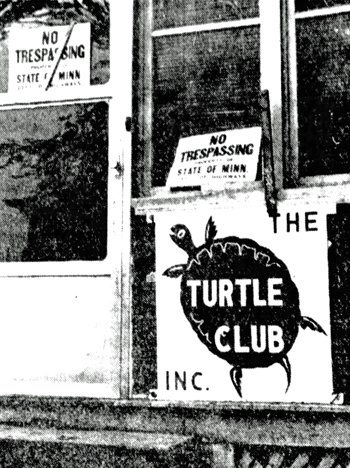

On September 18, 1959, the State Highway Department took possession of the Turtle Club and finally closed it for good. BUT… the article didn’t give the address of this particular Turtle Club, which was described as a two-story frame structure.

Minneapolis Star, September 19, 1959

582 RONDO

The Turtle Club wasn’t licked yet, and by 1960, it had moved on to 582 Rondo, where it stayed until the bitter end.

In June 1960, an ordinance regulating Bottle Clubs was being discussed in St. Paul. Mance’s son Rudy was identified as the operator of the Turtle Club. The ordinance passed. The Turtle Club was described as the best known of the bottle clubs, having a capacity of 200, with many of its patrons coming from Minneapolis.

The club’s application to renew its bottle license was rejected on June 30, 1963. The Turtle Club was no more. At least legally.

ONE SINK VS UNITED STATES

On October 9, 1963, an IRS Agent and St. Paul Police raided the Turtle Club, described as a “former bottle club,” confiscating liquor, fixtures, and gambling equipment. It’s unclear whether there were any actual customers in the place – no arrests were made, and the Turtle Club was never charged with a crime.

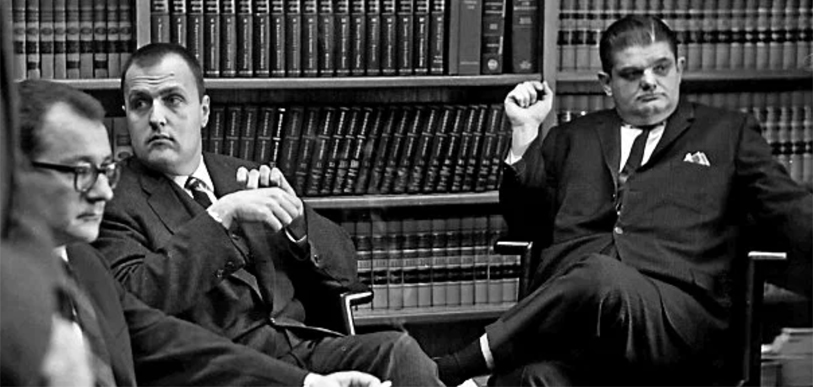

But as a result of the raid, St. Paul attorneys Douglas Thomson and John A. Cochrane filed a lawsuit entitled “One Sink et al. versus the United States of America.” The suit charged that the sink’s Constitutional rights were violated when it was “rudely torn from its natural appurtenance” behind the bar in the basement of the Turtle Club. The suit asked that the sink – and all items taken in the raid – be suppressed as evidence and returned to their natural state.

Assistant Federal Attorney Sidney P. Abramson, defending the USA in the case, asked the judge to throw out the case, claiming that One Sink had no legal claim – “without a stopper.” Thomson countered, “This case has been a terrible drain on our firm, but we feel we come into court with clean hands.” (Minneapolis Tribune, January 26, 1964)

Well, the hearing began before U.S. District Judge Earl R. Larson. The suit was in Federal court because of the presence of the IRS agent. On July 16, 1964, Larson “politely” threw the suit out, ruling that the sink did not have any rights under the 4th Amendment of the Constitution. Larson also held that the U.S. District Court did not have jurisdiction, because the IRS Agent had only observed the raid, which was planned and carried out by St. Paul Police. Cochrane opined that “We hope all our efforts have not gone down the drain.” (Minneapolis Star, July 18, 1964)

Not to be dissuaded, Cochrane brought the suit to the the Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis, but it was thrown out of that court as well, on July 17, 1964. Cochrane had failed to pay the $25 filing fee. (Minneapolis Star, July 18, 1964)

Douglas Thomson, John S. Connolly, John A. Cochrane, May 1, 1963. Photo by Don Church, St. Paul Pioneer Press

CODA

Booker T. Ellis died March 15, 1965, at age 43 and is interred at Fort Snelling

Rudolph Ellis died in November 1965, at age 42 and is buried at Oakland Cemetery in St. Paul.

Mance Ellis outlived both Booker and Rudy. He died in February 1972, at the age of 76 and is buried in Oakland Cemetery near wife Mattie and son Rudy.

Kamuel Ellis died in September 2013, at age 86 and is buried in Oakland Cemetery.

Jeremiah Ellis:

When viewed through a modern trauma-informed perspective, the consequences of forced closures of The Booker T and other Rondo community assets looms heavy on the misfortunes of Booker T. and Rudy Ellis in the years that followed. With their inheritance stolen, their early deaths in 1965 were hastened, Booker T. at 43 followed by Rudy Ellis at 42. The Ellis family is but one example of why the Minnesota Department of Transportation formally apologized for the decisions to demolish Rondo Ave., resulting in Interstate 94 in St. Paul today.