First printed in the newsletter of the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting

“The birth of Top 40 Radio came with the last days of Network Radio’s Golden Age. Entire station formats based on the ranking and repeated play of each week’s popular music hits began at Todd Storz’ KOWH/Omaha in late 1951, later refined at Storz-owned WTIX/New Orleans. Then it was picked up by Gordon McLendon’s KLIF/Dallas and KELP/El Paso following the collapse of McLendon’s Liberty Broadcasting System network.

“Word of the format’s ratings successes spread throughout the industry as Storz quickly added WHB/Kansas City and WDGY/Minneapolis-St. Paul to his chain and McLendon increased his holdings with KILT/Houston and KTSA/San Antonio. Within five years the Top 40 format, layered with Storz and McLendon types of ‘forced listening’ promotion, was copied by stations across the country and grew into a nationwide broadcasting phenomenon.” [“Forced listening” promotions were contests that required listeners to remain glued to their radios for clues or catch-phrases.]

from Jim Ramsburg’s Roots of Top 40 Radio at www.jimramsburg.com “

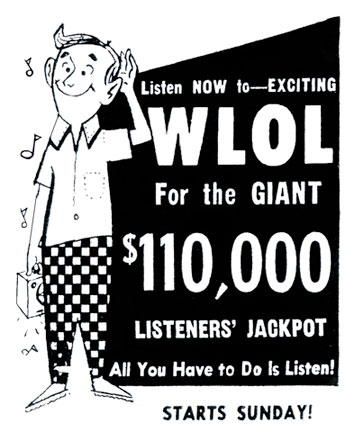

WDGY was the Twin Cities’ first full-time Top 40 station, going on the air with its new format on February 6, 1956. To call attention to WDGY’s new identity, Storz kicked off a cash giveaway contest craze that would involve almost every other station in the Twin Cities and force hopeful listeners to “stay tuned.” Examples of WDGY’s stunts, as listed in Television Magazine, included:

• The Auto Cash Contest, where listeners wrote in for registration cards for the rear windows of their cars. A station spotter on the road phoned in a license number of a car bearing a sticker, and if the listener called the station, he won the cash.

• Lucky House, where the station would broadcast a street address, and if the occupant called within a minute he got the jackpot, which increased up to $500.

• Dinner with the Disk Jockey, where the listener wrote a 25-word letter about what he liked best about the “new WDGY.” Four winners got LPs and were invited to have dinner with the jock.

• Mystery Voice, a “guess-who routine.”

• The Parakeet Contest, where cash was offered to any listener who could train his parakeet to say “This is WDGY, Minneapolis-St. Paul.” There actually was a winner!

At WHB in Kansas City, DJs threw cash off the tops of buildings causing monumental traffic disruptions and an occasional arrest – Todd Storz himself even got arrested once for tying up traffic.

WTCN got wind of WDGY’s plan to start its first contest on February 6, 1956, and started its own contest on February 1. KSTP joined the fray on March 7, with WCCO coming in on March 12.

In May 1956 Will Jones of the Minneapolis Tribune had plenty of jokes about the contests. Apparently Stuart A. Lindman of WTCN was running a contest where listeners sent HIM money (for charity). At the same time, WCOW had changed its call letters to WISK, and disk jockeys were standing in the streets handing out bills. At a broadcasters’ convention the gag was that “the listeners got paid more than the station executives.”

On June 7 WDGY hid a check for $105,000 somewhere within ten miles of the station. The check was underwritten by Lloyd’s of London and nobody at the station knew where it was. Each day the company would supply the jocks with a hint to broadcast and listeners had ten days to find it. Todd Storz announced that the check would be not more than 15 feet above nor more than five feet below ground. “Searchers are warned against the use of – and will not need – explosives, demolition equipment, or power tools.”

Things got really out of hand when people started planting phony checks and giving out false clues as to where to find them. The station claimed that when a hint sent searchers to Hennepin and Lyndale at rush hour, 20 policemen were required to keep order (a statement the police department later disputed). Herb Oscar Anderson remembers a guy with a mobbish accent who would call him at home and offer to “split it wich ya” if HOA gave him the location of the check, which was disconcerting to the DJ to say the least. Odds against find the check were estimated at 47 to one, and the station really had no intention of paying it out. Nobody found the check in the appointed time, and a $500 consolation prize was awarded to one of the estimated 200,000 searchers.

During the same ten days of WDGY’s contest, WCCO’s $250,000 Cashorama promotion gave away money if the station called a listener who knew a key phrase that had just been given out over the air. Bob Montgomery became “Big Bill Cash” and his job was to call eager listeners. Only $37,000 of the possible jackpot was eventually given away.

Bob Montgomery

One strange consequence of the giveaways is that WDGY started running ads for WCCO. WDGY started to broadcast WCCO’s phrases so that listeners wouldn’t have to move their dials from WDGY. Well, WCCO got wise and made up phrases like “WCCO is tops,” “Three million Northwesterns listen to WCCO,” “I always listen to WCCO,” “More people listen to WCCO than to all other Twin Cities’ radio stations combined,” and “WCCO, good neighbor to the Northwest.” WDGY had to give up that strategy.

KSTP’s “Treasure Chest Tunes” game gave out telephone numbers for Treasure Chest calls and songs had to be identified.

KEYD offered a $100 government bond if you answered their call with “I like KEYD, my country-western station, 1440.”

WTCN had several games going. One announced a telephone number and gave the owner of that number five minutes to call the station and claim the prize. A variation was when the station told listeners that somewhere between pages 20 and 528 in the Minneapolis phone book or between 20 and 400 in the St. Paul directory there was a mystery phone number. Listeners would dial numbers at random and ask “Is this the WTCN 1280 secret phone number?” Imagine how annoying that was. Will Jones of the Tribune laid out the station for that one. WTCN also had a “money wagon” cruising the streets.

An article in Variety commented that listeners were probably going crazy listening to the same records over and over again on these stations, waiting for their phone number or the magic phrase to come up.

KSTP’s Stanley Hubbard called it quits in July, calling it “a cash give-away fracas that has gotten out of hand and become a circus” as quoted in Variety.

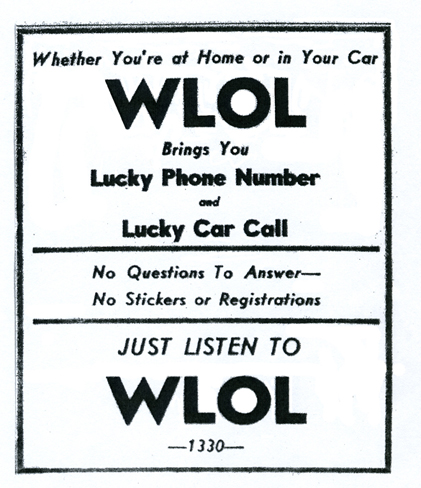

In the meantime, WLOL expanded its Lucky Phone Number contest, making 10 calls worth $1,000 each for 11 days.

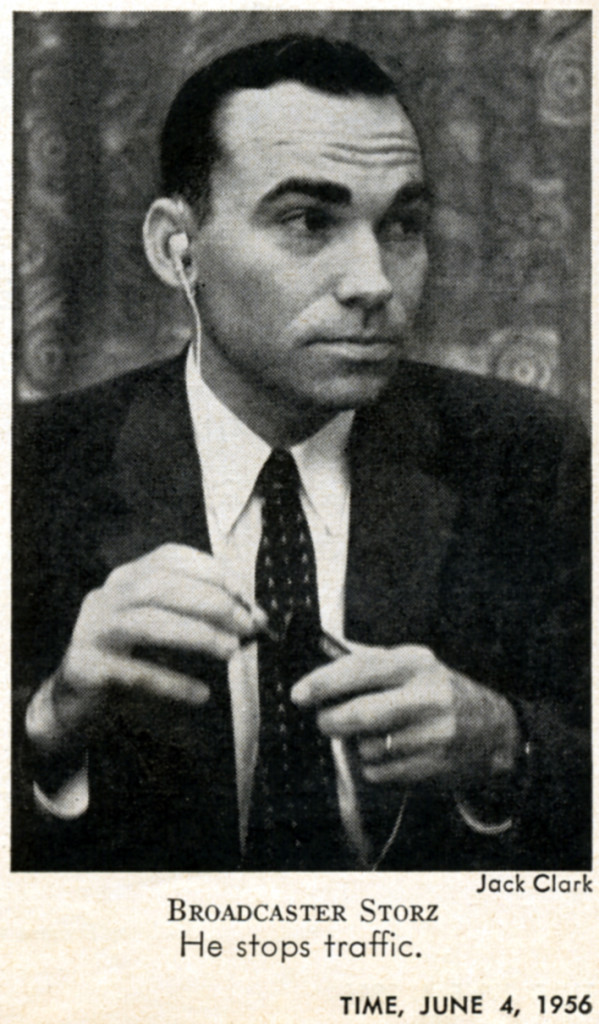

The giveaway fad abruptly ended in July 1956 as a result of Storz’s efforts to buy his fifth station in Miami. Just as the FCC was hearing the application, an article came out about Todd Storz in Time Magazine, with a picture of him captioned “He Stops Traffic.” (Note his omnipresent earphone as he constantly listened to the radio.)

The FCC was concerned about whether the disruptions in the cities where the contests were held were consistent with the role of radio as in the “public interest, convenience, and necessity.” They could have either not approved the license or required a hearing, which would would take the proceeding past the August 15 expiration of the contract of sale and put the kibosh on the deal.

To assuage the FCC, on July 18, 1956, Storz signed an affidavit that he would discontinue the giveaways at all of his stations. The affidavit was printed in Broadcasting Telecasting Magazine on July 23, 1956, as follows:

Gentlemen:

Mid-Continent Broadcasting Company has pending before the Commission the above-numbered application seeking the Commission’s consent to its acquisition of control of Miami Broadcasting Co., licensee of stations WQAM and WQAM-FM Miami, Fla. On July 12, 1956, the applicant received the Commission’s “McFarland” letter of July 11 advising of the possible necessity of a hearing and promptly filed a detailed reply with the Commission on July 16, 1956.

After the filing of the reply, the President of Mid-Continent Broadcasting Co. discussed the subject matter of the Commission’s “McFarland” letter with several of the commissioners. As a result of these discussions, the proposed transferee wishes to make the following additional showing.

Until the Commission’s McFarland letter was received on July 12 the proposed transferee was unaware that the commission looked with displeasure upon certain types of “giveaway” programs and promotions. Mid-Continent Broadcasting Co. is of the opinion that all contests, promotions and “giveaways” carried by the applicant’s stations are legal and well within the Commission’s Rules and Regulations, and that its programming is in the public interest. However, since it appears that the commission, by virtue of its July 11 letter, has some doubts on the propriety of contests and “giveaway” programs and in an effort to obtain consideration of its application before the potential termination date of the contract on Aug. 15 we agree to abide by the apparent desire of the Commission and make the following representation:

“Mid-Continent Broadcasting Co. will, upon the Commission taking favorable action on the instant application involving stations WQAM and WQAM-FM, discontinue all contests and/or ‘giveaway’ programs designed to attract audience or influence listening over all broadcast facilities operated by it as soon as possible”

(notarized)

The article’s introduction to the letter as printed in the magazine says “The FCC, however, did not consider this letter in reaching its decision to approve the transfer.”

Thus WDGY ended its contests and the rest of the stations mostly followed suit, although WLOL was still doing its Lucky Phone Number and Lucky Car Call contests in December, as was WMIN with a One In A Million contest.

The contest tradition continues today, of course, but stations have tightened up on listeners’ privacy and try not to tie their cities’ streets into knots.

Jeanne Andersen

Epilogue:

On April 13, 1964, Todd Storz, the King of Top 40 Radio, died from a cerebral aneurism at his home in Miami Beach, Florida, at the age of 39.

Six years later, on July 3, 1970, Casey Kasem’s American Top 40 was launched on seven different radio stations, the very first being KDEO in El Cajon, California (now KECR). The number one song on his list was Three Dog Night’s cover of Randy Newman’s “Mama Told Me Not to Come.” Kasem hosted the show from its inception in 1970 to 1988, and again from 1998 to 2004. In his sign-off, he would tell listeners, “And don’t forget: keep your feet on the ground and keep reaching for the stars.” Casey Kasem passed away June 15, 2014, in Gig Harbor, Washington, at the age of 82.

WDGY/1130 AM abandoned its Top 40 format for Country/Western in 1977, before dropping the WDGY call and becoming KFAN in 1991. The WDGY call letters were then adopted, and still used today, by KDWB (WDGY’s old rival) at 630 kHz.

In spite of being dubbed “The Giveaway King” by critics, the foundation of Storz programming was the simple premise that what the public wanted was popular music. He took the position that his own tastes or the tastes of his managers or talent were immaterial and not even to be considered when it came to programming.

Even Bud Armstrong, manager of the Storz Kansas City station, WHB, issued the following warning to his disk jockeys:

“About the time you don’t like a record, mama’s just beginning to learn to hum it. About the time you can’t stand it, mama’s beginning to learn the words. About the time you’re ready to shoot yourself if you hear it one more time, it’s hitting the top ten.”

When Todd Storz replaced traditional programming with Top 40 he was generally criticized by the rest of the industry, to which he replied, “At times, it seems that nobody likes our programming but the listeners.”

Steve Raymer